This text is a translation of articles published in Italian magazines Dinamopress and Not

"But while in the ancient world the machine may still be a symbol of unity with nature, or the product of out-of-the-ordinary ingenuity (such as the self-propelled automata of Heron of Alexandria), with the arrival of industrial civilization and modernity that laceration between man and nature, which was already expressed in myth but retained a hope of recomposition, is now irremediable."

Antonio Caronia, Robots Between Dream and Work, 1991.

"From this point of view, knowledge can be described as a living organism [...] And while it lives, it lives of and in the interpretations of the actors who interact with it: whether it is the people who use this knowledge for their lives or to make more of it, or whether it is the computational entities that collect this knowledge for some reason, whether it is to make it accessible in some way by a search engine, or whether it is to try to process it with the processes of artificial intelligence."

Salvatore Iaconesi, The Spiral of Knowledge, 2020.

In his publication Futuredays - A Nineteeth century vision of the year 2000, science fiction writer Isaac Asimov reported in 1986 on a series of 25 cartoons dating back to the end of the previous century and published in 1910, En l'an 2000, in which French illustrator Villemard depicted the predictions and fantasies of the time about technology and its applications 100 years since then. The various postcards show futuristic means of transportation and machines of various types capable of replacing human and manual labor. Two things are mainly striking: one, of course, is the obvious utopian and positive meaning of the presence of machines taking the place of human beings in daily tasks; the other is the mechanical representation of the devices in a way to be similar to organic structure they replace. Thus, for example, a tool for cutting hair has mechanical arms and hands with which to grasp scissors and a comb, an automatic household tool for cleaning floors consists of a stand on wheels that wields a broom and dustpan, while instead to transfer knowledge into the heads of pupils a school has a machine that literally ingests books by converting them and sends the notions to the children via cables connected to their heads.

On the other hand, in many cases, science has tried to obtain technologies capable of simulating human faculties by attempting to faithfully reproduce the structures that enable them for us, but the more the faculty involved relates to the cognitive sphere, the more we run the risk that this approach will lead down a false track, as well as create confusion and misunderstanding in the use of these technologies. When we say that a machine - be it an Olivetti Studio 44, a Mac or a smartphone - is writing, we certainly do not think of it as having pen and notebook hands, just as flying machines do not require wings. The analogy between human and machinic writing, then, reaches a certain level of depth, the limit of which is known to anyone. The moment, however, we say that a machine thinks, or even does so thanks to neural networks and artificial neurons, here is where the confusion increases, and we are no longer able to understand exactly what it means that it thinks, how similar its thinking is to human thinking, or how far it can go in simulating our thinking.

The term Artificial Intelligence actually encompasses a very wide range of techniques and methods. Products such as Midjourney, ChatGPT, and the like have introduced so-called "generative models" to the general public, rightly sparking enormous debate and has shown in a still developing way the impact of these technologies throughout the social sphere. I will try here, meanwhile, to shed light on the nature and structure of these tools and briefly analyze the role they are taking on in a constantly accelerating world.

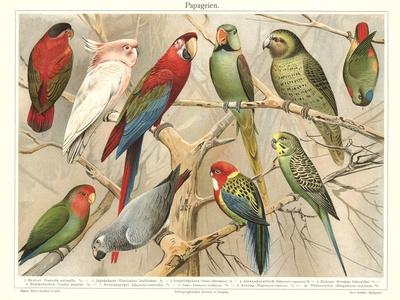

Stochastic parrots and where to find them

In their celebrated paper On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?, a group of U.S. researchers sounded the alarm about the risks and criticalities in using so-called Large Language Models (LLMs), language models such as GPT and their derivatives. As they rightly point out, these technologies are not capable of understanding text, but cascade a series of words from previous ones, according to a certain structure and coherence. They are, to use the paper's analogy, stochastic parrots, assigning a certain probability to the terms to be written. Making this clarification is useful to reduce the hype associated with these technologies, thus to avoid misunderstandings of their use to the general public. Also in this interpretation one can point to useful guidelines for research to follow. So we come to the question: what can and what cannot ChatGPT do? In recent months so many people have been testing, studying, and experimenting with its capabilities. ChatGPT's technical training specifications are now not public domain, but we must think of a language model as a mechanism for composing sentences, where text structure is learned, but precise references fade out.

Science fiction writer Ted Chiang wrote in February this year in "The New Yorker" one of the best articles to come out on the topic of AI: ChatGPT Is a Blurry JPEG of the Web. Chiang begins by recounting how in 2013 a German photocopying company noticed that one of their machines when copying a floor plan with square footage values on it (such as 14.13, 21.11, 17.42), always inserted the same number (14.13) in the final copy. They realized that the fact was due to the compression method, which, to save memory, associated all the numbers with the same symbol and then repeated them where they were present. The photocopy was a blurry replica of the original. The same is true for ChatGPT: a blurry copy of the entire web. Passing off an LLM as a substitute for a search engine (as proposed by Microsoft with Bing and by Google with Bard) is wrong and dangerous, because searching for references is not the task it is trained to do. Of course, there are also services that, in addition to the textual response, provide the links used to construct the response, but at that point we might as well use a search engine. On what then does a language model go strong? On what specifically relates to language: translations, summaries and rephrases. These are the activities on which it is trained, although it can obviously show reversals of meaning in particular cases.

There is another fact that has intrigued me over the past few months: people with no background in computer science have been extremely surprised to see ChatGPT's ability to produce code like algorithms to perform a given task or to produce websites. Personally, among the various features of the product, it is the one that surprised me the least: to a human writing code may seem a complex operation because it requires specific skills, but a code that performs a certain operation is almost always written in the same way, and the Web is full of such writings. It is, after all, well known that there have long been forums and website, for example the huge community of Stack Overflow, where code for specific operations is shared between users. In short, writing codes is one of the most parroting activities that exist. Of course, this is true for simple tasks, and in fact it is easy to see that if ChatGPT produces more complex codes, they often contain small errors that still make human control work essential.

Another fundamental element of the issue is that, if ChatGPT exists, it is because it has been able to stand on an exorbitant amount of information collected and constructed by each of us on the Web (in addition to the work of armies of underpaid cleaners), making it accessible through an interface. It thus exists through collective and distributed network work. With a bit of irony but not too much either, I would be inclined to say that artificial general intelligence already exists and was born on August 6, 1991, when the decision was made to create an infrastructure to collect and contain in the years to come the largest collection of human knowledge. Compared to this leap, ChatGPT (and LLMs in general) is but a small piece added.

OpenArt prompts: Interior of an ancient library filled with studying scholars, papyrus, watercolored, jakub rozalski, dark colours, dieselpunk, artstation.

Work, copyright, and all the old that doesn’t die

With the advent of ChatGPT & Co. have also come doubts and fears about the future impact of these technologies in public life. According to the World Economic Forum's study, The Future of Jobs Report 2023, three-quarters of the world’s leading companies expect to adopt AI in their organization, and 50% believe it will spur job growth while just 25% say jobs will be lost in different fields as healthcare, manufacturing, agriculture and recruitment. Now there would be the question of what specific technologies we mean by artificial intelligence. As far as LLMS is concerned again, to understand what is and what will be able to happen we only need to take up the discussion regarding what these technologies can and cannot do. Certainly ChatGPT is a tool that will dramatically reduce a translation task, especially one that does not require special stylistic attention and is already probably reducing the workforce required of a newsroom. At the same time, however, even this task will not be completely replaceable, because a human figure will always be needed to check the correctness of the result or to advise in the case of specific translation choices.

Still, GPT could be useful in the editorial office of a junk news outlet, where the employees' task is to take texts from news agencies and reframe the content a bit in order to thus publish 10 articles per hour. In short, surely ChatGPT will be able to save time in the case of repetitive and unrefined work that has to do, precisely, with language manipulation. The scenario that seems to be shaping up is one defined as "human in the loop," that is, a process in which a human figure is present as a supervisor of the activities of an AI, and the more the knowledge requirements of the profession increase, the more central the supervisory figure will be and the job position will be less at risk. We can say, also with a bit of incitement, that AI work replacement is an indicator of bullshitness of jobs, or of specific job tasks.

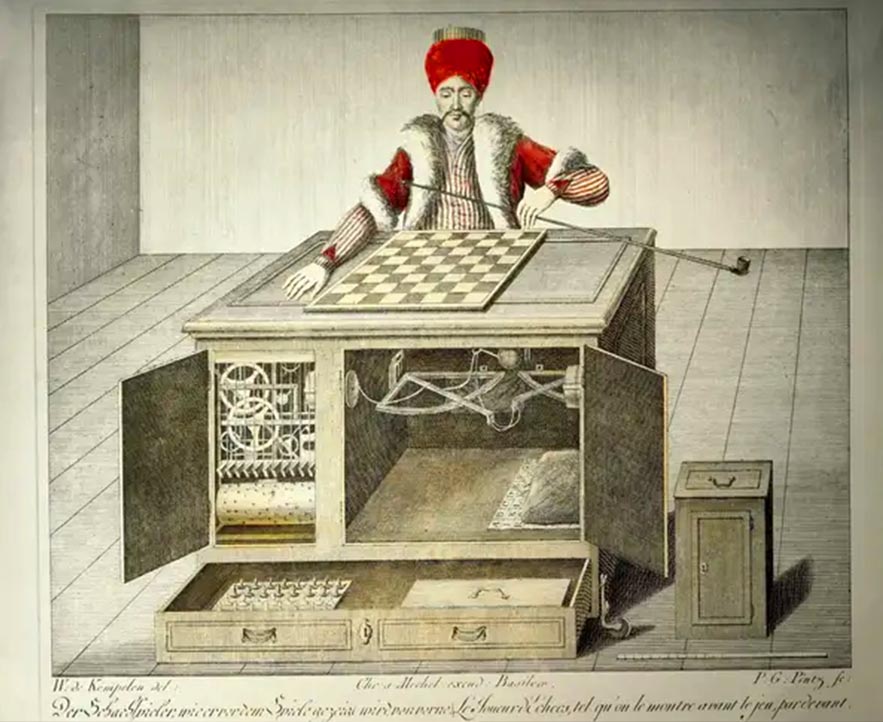

We have also to remind, to don’t fall in the myth of abstract and ethereal AI, that ChatGPT production process involves not only controllers with special qualifications, but also the army of workers in Kenya, Uganda, and India who are exploited at 1.50 euros per hour to tag hate speech, expressions of sexual violence, and other explicit material to "fix the machine”. This is nothing new, as we already know from documentaries as The clenears or studies about hidden platform workforce in so-called Mechanical Turk phenomenon (such as analyzed for examples by Antonio Casilli or Matteo Pasquinelli).

Another big issue much debated in recent months concerns the use of material found online for training machine learning algorithms and thus the regulation of relationships, economic and otherwise, between those who produced that material and the owners of the algorithm. Artists, programmers and content creators of various kinds have spoken out in recent months, against the misuse of their works by AIs. As surely as these actions represent demands for the protection of endangered forms of work, I believe that any battle for the defense or a return of authorship-based remuneration beyond rearguard action is already lost in the face of the evidence of the mechanisms of knowledge production.

With the advent of digital, thus the virtualization of a work product untethered from a specific medium, it was clear that authorial attribution was moving toward its impossibility. Even reformist attempts related to the open source and Creative Commons galaxy pose many limitations: as much as one can put a "No Commercial Use" sticker on a Github repository, once a software development or algorithm idea is circulating, and thus can be re-implemented, in that or another language, authorship has vanished, and only with our eyes closed can we see how the corporate and corporate world has in recent years exploited the vast open source knowledge as a free mining ground.

AI are just one more step in this direction: data can be restructured, reformulated, used as training to build a product. The struggles and demands for the protection of cognitive labor are fundamental, but they take on strategic value when considered in a path toward a politics of universal income untethered from labor (together with the request for high-taxation of the big tech corporations), and the new technologies scenario offers this path an opportunity for space in the public debate that should not be let slip away. In addition, from experiences as italian case of GKN and new projects in the tech environment comes a suggestion that it might be interesting to start discussing and understanding, among workers in information and technological development, that is, if and how it is possible, in addition to the regaining of labor rights, also to redesign production and, why not, also to redefine the purposes and directions of development of artificial intelligence from below, in a perspective of welfare, useful community services and ecological conversion.

Technic and magic: platform animism and linguistic turn 2.0

In Fredric Brown's short story, The Answer, the protagonist Dwar Ev finally brings to fruition his realization of a supercomputer, which by connecting all the calculators on all the ninety-six billion planets in the universe could encapsulate all the knowledge of the universe in a single machine. After soldering the last two wires, Dwar lowers the lever, activating the creation and asking it an initial question, "Is there God?" Without hesitation, the machine replies, "Yes: Now God exists." Seized with terror and regretting his creation, Dwar tries to throw himself on the control panel to turn off the machine, but lightning from the sky incinerates him, nailing the lever forever in place.

At the end of March, a letter signed by entrepreneurs, authors and industry experts including Elon Musk, Yoshua Bengio, Steve Wozniak and Noah Harari was published on the Future of Life Institute website, calling for at least a six-month suspension of advanced research in the field of artificial intelligence, in order to allow the legislative environment to adjust to the regulation of these technologies, while development should ensure transparency and accountability. The letter hides not too covertly the real purpose: to generate hype. "Look at us, we are the Victor Frankensteins of the 21st century, the Dr. Faust who sold our souls to the New Mephistophele," is the letter's paraphrase.

Not coincidentally, the language of the letter thus hints at a set of ideologies that are settling among the upper echelons of Silicon Valley, expressed by an increasingly popular acronym: TESCREAL (Transhumanism, Extropianism, Singularitarianism, Cosmism, Rationalism, Effective Altruism, and Long-Termism"). A term critically coined by Timnit Gebru (former Google employee and author of the paper on parrots mentioned above), within three years hi-tech leadership has appropriated the word, such as entrepreneur Marc Andreessen, who calls himself a "TESCREAList" (as well as an "AI accelerationist," "GPU supremacist," and "cyberpunk activist") in his twitter biography.

The terms of the acronym refer to a number of philosophies and currents that have sprung up around transhumanism and its declinations: deep enthusiasm for technology as a means to overcome the limits of human beings (disease, aging and death), race to space, realization of strong AI as humanity's missions, employment of development and rationality to transcend the material and bodily condition, then striving for the divine condition through technology. Someone rightly referred to the concept of animism to describe the conception that the idea of artificial intelligence is taking on in these circles. In a tweet of his own last February, the (maybe ex-) CEO of OpenAI (ChatGPT's company) suggested as a use for his product that it replace health care for those who cannot afford it. Beyond the boorish classism of such a statement, it is clear that communication on the part of these giants is directed toward an enthusiasm completely untethered from reality. And there is little point in recriminating the average user if the latter does not understand the proper use of technologies, if such messages come from on high.

February 2023 saw the launch of Bard, the AI chatbot with which Google promised to undermine OpenAI's ChatGPT. But within hours of the unveiling event, in a promotional video the Mountain View assistant gave an incorrect answer to the question posed, claiming that the James Webb Space Telescope would be used to take the first photos in history of a planet located outside the solar system (exoplanet), whereas the first exoplanets were photographed thanks to ground-based telescopes even 14 years before James Webb's launch. An oversight that has not gone unnoticed or forgiven especially by the financial world. On Wednesday, Feb. 8, Alphabet's stock closed down nearly 8 percent, down $100 billion from its market value. And the error just so happens to be about specific knowledge rather than an error in language composition, which is what it was trained to do. The Silicon Valley giants, in short, found themselves victims of their own hype.

We were already accustomed to the power of language in finance, as it may be in the case of a CEO's one-liner, but to think that now this linguistic power also accrues to machines leaves at least a sense of concern. Douglas Adams' scene in his Intergalactic Guide comes to mind, when after seven and a half million years a crowd of onlookers anxiously awaits from Deep Thought the answer to the fundamental question about life, the universe and everything. Christian Marazzi wrote in his The Place for Socks, "When we say that, with post-Fordism, communication enters into production, becomes a directly productive factor, we are calling into question language, which, by its very vocation, lies at the basis of communication. The coincidence of the act of producing and the act of communicating in the new production paradigm opens up a range of problems of language analysis that are as fascinating as they are extremely complex and dense."

With the advanced capitalism of artificial intelligence we are witnessing a linguistic 2.0 turn, where language takes on an even more central productive role. It is a kind of magical capitalism, where language and its oracle-dictated formulas are able to act more and more on the real. A magic that self-reports itself as abstract and immaterial, but we know to be embodied in social and material processes, in the whims of Silicon Valley and high finance. The challenge is to disenchant technology, liberating it from the tescrealist imaginaries and constructing others beyond anthropocentrism and extractivist ambitions.

Opening the black box

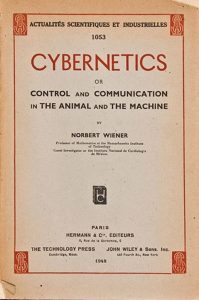

In early 1949, in the laboratories of Barnwood House Mental Hospital, a private asylum on the outskirts of Gloucester, it was possible to find a mysterious square black device composed of four accumulators, each equipped with a magnet capable of oscillating between different configurations. As reported in a Time article at the time, according to its creator, psychiatrist William Ross Ashby, this device, the so-called homeostat, was the closest thing to the realization of an artificial human brain ever designed by man so far. Ashby, in addition to being a physician, was one of the pioneers and popularizers of cybernetics, which rather than a discipline could be viewed as a range of interdisciplinary experimental studies straddling engineering, biology and social science, the origin of which can be traced arbitrarily back into the past depending on which roots of systems thinking one wishes to consider, but it is certain that in the immediate postwar period the name of this new science was introduced and popularized by the work of Norbert Wiener, who published his Cybernetics or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine in 1948.

The U.S. mathematician's intentions, as expressed by the title of the work, were to found a new science capable of addressing issues of regulation of natural and artificial systems by finding similarities and affinities between them, hybridizing methods from the social and biological sciences with theories of computation and automatic control. The same principles then inspired Ashby, who jotted down his thoughts for over 44 years in a series of diaries producing 25 volumes, totaling 7189 pages, now entrusted to the British Library. And it was precisely in order to give an example of a self-regulating machine that Ashby constructed the homeostat, whose state could be altered by particular commands representing the external environment, and which under particular conditions was capable of returning by itself to a state of equilibrium. Hard as it is to imagine now, such a design was absolutely in line with the goals of the nascent branches of automation, so much so that Turing himself, knowing of Ashby's intention, wrote to him proposing to simulate this mechanism on the calculator he was designing near London.

But what interests us about Ashby's complex machine in order to be able to find a key to the developments in automation to follow up to our own years is the approach with which the homeostat was realized in wanting to simulate a living system. The model proposed by Ashby is what came to be referred to later as black box theory, black box method, on which cyberneticians themselves initiated a heated debate that we can still hold open today. Ashby himself wrote in the 1950s that "what is being argued is not that black boxes behave in any way like real objects, but that real objects are in fact all black boxes, and that we deal with black boxes throughout our lives," essentially suggesting a black box ontology. The role of the black box in science is a dilemma that arrives, re-exploding, in the 21st century. It is Latour himself, in 2001's Pandora's Hope, who speaks of blackboxing as "the way in which scientific and technical work is made invisible by its own success. When a machine works efficiently one focuses only on input and output, and not on internal complexity. This causes, paradoxically, the more successful science and technology gets, the more opaque and obscure it becomes."

Taking another leap of years and coming to very recent times, it is no coincidence that concerns about opaque science have emerged in the field of artificial intelligence, where the need to understand the reasons for one automated choice over another, or the classification parameters it makes use of, has emerged. This has led research to develop, for example, the so-called Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) branch. The black box problem, however, is not simply a technical issue, but something that is increasingly concerned with the social, economic and cultural spheres, thus involving the study of the effects of AI in a complex sociotechnical system. To be black box is not only AI in the strict sense, but also distributed computational intelligence, that composed of a harnessed network of calculators, IoT devices, hyperconnected bodies in motion and in constant production. Becoming a shadowy organism is the financial machine, full of metaphysical subtlety and theological whimsy, so complex that it is barely understood by palace shamans, too busy now fighting those high-frequency algorithmic demons they themselves conjured up eons ago, and of which they have now lost total control. Finding itself increasingly opaque is science, not because of a lack of information or intelligence, but because of the increasingly fragmented microdisciplinary breakdown, toward a hyper-specialization unable to communicate with the rest of the world. We can, then, speak of black box societies, as suggested by Frank Pasquale, and try to make partial considerations about those hyperobjects that govern our lives at the limit of comprehension, in what Bridle, quoting the master of horror Lovecraft, considers a new dark age.

Returning to Latour, and to the text he wrote with Steve Woolgar, Laboratory Life, "the activity of building black boxes, of making objects of knowledge distinct from the circumstances of their creation, is exactly what occupies scientists most of the time. [...] Once an object of study is processed in the laboratory, it is very difficult to turn it back into a sociological object. The cost in detecting social factors are a reflection of the importance of black box activity." Opening the black box, then, is not just a task for experts or technicians just as, returning to Bridle, although it may be useful it is not necessary to learn programming in order to approach the debate about new technologies. On the contrary, what is emerging from new strands of research such as social network analysis or computational sociology is that the computer science and "hard" science environment has found itself catapulted in a very few years to confront questions of method with which it was not used to interfacing, unlike sociologists, psychologists or humanists. Therefore, not only is interdisciplinarity necessary, but also a critique of production processes capable of recognizing the dynamics of value, labor, and the impact on the environment of open systems. In this sense, of this distributed opaque intelligence, or at least of a small part of this megamachine, we can also try to open some black boxes with the tools of “collective bottom-up research”, with surveys in the places of digital production and sociology from daily life. Into the Black Box, is "a collective and trans-disciplinary research project that adopts logistics as a privileged perspective to investigate current political, economic and social mutations." Logistics as a form of strategic intelligence in the narrative of harmonized, self-regulated production. The articles on the collective's website and the events organized, mainly in Bologna, offer very useful interpretive keys to read the black box society by widening the gaze "inside and beyond the screen," offering an interesting insight into political and strategic praxis as well as analysis. Project like this, inside and outside academy, are increasingly necessary.

It was the 17th century, and Gottfried Leibniz was developing his system of mathesis universalis, a symbolic method capable of resolving any controversy through computational processes. It was 2008, and Chris Anderson proclaimed on Wired the end of theory by virtue of the age of data and correlation. Since then, time has passed, and to some extent even in the academy the hangover for big data has passed, partly as a result of the cases known to the news of problems that arose from uses of AI technologies without an adequate epistemological apparatus: the Tay bot of Twitter, the COMPAS case and other news cases now well known in the academic literature. Thus we begin to talk about bias, research on AI branching out into the fields of explainability, trying to open the black box of decisions and understand the mechanisms of decision-making. With respect to LLMs, in particular, reference is made to stereotypes conveyed with language, or even there are those who speak of "bias" and "vulnerability" in the case of getting chatbot responses that are not in line with policy. The dream of the correct artificial intelligence is that of a technology that thinks and communicates like humans but without lying, without having judgments and without talking nonsense, basically that does not think and communicate like humans. However, even in the academic literature it is now recognized that the term bias itself is used with different meanings and intentions, making the debate on the topic increasingly confusing. In sociology the term bias has a definite meaning and indicates a possible error in the evaluation or measurement of a phenomenon due to research techniques, a distance between the phenomenon studied and its measurement. We could then establish, that bias for AI is a difference, between a benchmark considered standard case or null and an artificial model. And here we come to the point: when we talk about racist or sexist bias of an AI, or even bias due to vulgar language, with respect to what are we claiming there is a distance? What is the null model?

If we consider that the texts most commonly used for training come from large web platforms, we find that we are already making a very specific choice of language type and interpretive paradigm. According to 2016 Pwe Internet Research, Reddit users are 67 percent male from the United States, with 64 percent between the ages of 18 and 29. Other studies regarding the composition of the Wikipedia community find between 8-15% are women. What will an AI trained on these platforms think or feel about colonial expansion? What will it answer when someone tries to ask for advice and information about abortion or gender transition, depending on which country it refers to? The answer will always depend on what information, texts and materials were used to train the machine. The point is not to improve or correct the model, the point is that any representation of the world and any form of expression is situated, is positioned in a specific social, historical context and therefore in a specific situation of privilege. Eliminating bias is a meaningless demand, since neutral discourse does not exist. The search for a phantom fairness of AI, aligned with social canons and mores, can only reckon that canons and norms are situated geographically, socially, historically.

In 2008 a New Zealand nonprofit Māori radio station named The Hiku Media, initiated a project with the purpose of training algorithms on 300 hours of conversation in the Maori language while maintaining control over their community's data. After Aotearoa, the Māori name for New Zealand, became a British colony in 1840, English took over as the local language, only to be imposed as the only language in schools 30 years later. As early as 1970 Māori inhabitants and activists established schools to preserve their language, but due to depopulation and urbanization the percentage of speakers had plummeted from 90 percent to 12 percent. It was not until 1987 that Te Reo was recognized as an official language. With the advent of digital technologies, the community is again at a crossroads. "If these new technologies 'speak' only Western languages, it is inevitable that we will be excluded from the digital economy," says Michael Running Wolf, a Cheyenne developer involved in AI projects for language conservation. "Data is the last frontier of colonization."

The Hiku Media does not want to upload data and information to Facebook and YouTube or leave it under licenses that do not allow for community control. "Data is the last frontier of colonization [...] Our data would be used by the same people who deprived us of that language to sell it back to us as a service [...] It's like when they take your land and then sell it back to you," project members state. Again, the open source culture runs into a problem of decision-making about data use, so The Hiku created a specific license that makes explicit the ground rules for future collaborations, based on the Māori principle of kaitiakitanga, or protection, granting access to the data only to organizations that agree to pass on all the benefits derived from its use to the Māori people. Obviously large companies, also observing this and other experiments, are already building their own archives of local and native language data and building business models from this perspective. What will make the difference in this process will be the balance of power between the parties involved.

Located in Langfang China, Range International Information Group is the world’s largest data center and occupies 630.000 square meters of space.

Geopolitics, regulations and microchips

The ethereal and disembodied idea of AI clashes not only with the materiality of the work but also with the impact this technology is having in international dynamics. For China, the AI race has taken on a pivotal role, both for the development of domestic industry and on the level of geopolitical confrontation, especially with the United States, so much so that, Xi Jinping himself has mentioned the topic several times in his speeches. During the Covid period, the use of digital and smart technologies as population control tools was evident, between temperature measurement and automatic facial screening within the social credit project. AI goals include the concept of smart cities, then high-speed interconnected infrastructure (5G and IoT), a full integration of the digital sphere into economic and production planning. The importance of AI in China is demonstrated by the fact that the search engine Baidu created a Chinese-language alternative to ChatGPT in March, called Ernie.

Obviously, in the context of international confrontation, the need for intelligent technologies in the field of warfare is becoming more pressing. In the war in Ukraine, NATO's technological superiority has allowed Kiev's forces a range of battlefield performance that is not insignificant in the eyes of other nations. The Chinese military has identified various fields of AI interest, from driverless automated vehicles to remotely operated drones, with all the ethical implications these technologies entail. The Pentagon estimates that the People's Republic is at a level of AI development equal to that of the U.S. so much so that the National Security Commission's final report on artificial intelligence states that "China's plans, resources, and progress should worry all Americans. In many areas, Beijing has equaled the levels of the United States and is even ahead in some."

The AI war is not limited to software development, it also extends to the physical part of the technologies and the raw materials to make it. While it is indeed difficult to control intangible labor products such as algorithms, it is significantly easier to control raw materials and microprocessors, the main reason for friction over Taiwan between the U.S. and China. Taiwan is home to the largest industrial system for chip production in the world. Sixty percent of the global market and 90 percent of the most advanced microchips are produced on this island. Tmsc (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company) is known as the leading semiconductor manufacturing and assembly industry in the world. In 2020 Donald Trump had convinced Tsmc to invest in Arizona after blocking its exports to Huawei. Tsmc has had facilities in mainland China for several years, and the link with Beijing has always been maintained, although it has always avoided exporting microchips for military use to China. The semiconductor war between U.S. protectionism and China's quest for independence represents one of the most important challenges of the 21st century, with possible consequences and spillover effects on the entire international politics.

And the European Union, what is it doing? On June 14, the European Parliament gave the green light to "The Ai Act," which is expected to be passed at the end of the year. The regulation establishes obligations for AI system providers and users depending on the level of risk, banning social scoring and real-time facial recognition systems. Instead, biometric identification at a distance and after the fact would be possible, and only for the prosecution of serious crimes.

One substantial work in the text is having to specify what is meant by AI, the definition of which, even technically, is not so obvious. Thus, various types are considered: machine learning systems, logic-based systems, and knowledge-based systems such as ChatGPT. The field is vast, while methods and timing for companies to adapt to these standards will be up for discussion. Regarding generative models, the policy request is to have transparency in the recognition of AI-produced material to counter deepfakes and automatic creations mistaken as human. In addition, NGOs and associations have pointed out that the limits imposed, including predictive analysis or automatic recognition, are not applied to protect migrants but only European citizens. "Unfortunately, human rights advocacy in the European Parliament also failed to include protecting migrants from the abuse of artificial intelligence, which can be used to facilitate illegal refoulement," said Sarah Chandler, spokesperson for the European Digital Rights network, which brings together 47 human rights NGOs. "The EU is creating a two-speed regulation, where migrants are less protected than the rest of society."

Capitalist realism and algorithmic realism

There can be no real conclusion to this text. Globalization and digital turbo-capitalism have in recent years always placed us in front of ever larger hyperobjects that are difficult to understand and counter, such that they leave us in a state of bewilderment and helplessness. Technopolitical and alternative platform responses to capital must, however, come to terms with the human and environmental costs involved in these technologies, and OpenAI has not disclosed any specific data on infrastructure emissions. A recent study by researchers at University of California, estimated the water proofprint of AI models like GPT, considering an usage of 700,000 litres of freshwater during models training in Microsoft datacentres, the equivalent of water needed to produce 370 BMW cars or 320 Tesla vehicles. Also from the stochastic parrots paper, "If the average human is responsible for about 5 tons of CO2 per year, training a Transformer model emits about 284 tons. Training a single BERT model on GPUs is estimated to require as much energy as a transatlantic flight”. Surely since paper’s publication high-performing technologies and algorithms are reducing costs and amount of raw materials, but we also know that in capitalism production chain less costs doesn’t mean less exploitation, it’s quite the opposite.

What to do then? Some ways of action can be suggested by the coming together of tech workers and those marginalized and/or oppressed by technologies, with a view to rethinking the forms of technology and its goals. Informal unions such as Tech Workers Coalition or the wave of Big Quit labor refusal and, of course, the transfeminist and ecological movements are symptoms of rupture toward a system that is now collapsing, signals that can and should find timely convergences. Another consideration may come from the fact that the discursive framework and hegemony of capitalist realism also rests its foundations on an assumed superiority and inaccessibility of technology and technology: redistributing critical knowledge then becomes not only a means of making the world we live in understandable but also a political issue. Academic and educational circles are increasingly steeped in entrepreneurial and neoliberal rhetoric, and especially the technical fields, where we are also seeing an intensification of collaborations between science and capital in the military (an association that Nolan reminds us is long-standing...). Rethinking a technical and scientific culture and education decoupled from extractive logics then turns out to be another key tool on the road to climate and social justice.

Daniele Gambetta graduated in mathematics and is now a doctoral candidate in artificial intelligence at Pisa University. He is an editor of the anthology Datacrazia (D Editore, 2018). Over the years he has collaborated with various Italian magazines and newspapers with articles on science and technology topics such as Fanpage, Vice, ilManifesto, Pagina99 and others.