In the early 2010s, the Sad Girl figure became popular online, expressing her emotions in selfies and Tumblr texts, creating a public vulnerability, posted from the private realm of the bedroom. The accompanying theory about the power of the Sad Girl came into existence in 2014, first expressed by US artist Audrey Wollen. Igniting on her -now deleted- Instagram page, Wollen spread the Sad Girl Theory in online magazines such as Dazed:

“Sad Girl Theory proposes that the sadness of girls should be recognized as an act of resistance. Political protest is usually defined in masculine terms – as something external and often violent, a demonstration in the streets, a riot, an occupation of space. But I think that this limited spectrum of activism excludes a whole history of girls who have used their sorrow and their self-destruction to disrupt systems of domination. Girls’ sadness [...] is a way of reclaiming agency over our bodies, identities, and lives.”

Wollen imagined a paradigm shift in activism, changing what acts could entail as activism, making the act of posting a selfie whilst crying something in conversation with feminist theory. The camera, selfie camera to be exact, was the main tool to do so. This makes the sad selfie an informed response to the patriarchy, going beyond teenage angst, neither narcissistic nor shallow. The artist further explains the usage of “girl” in her Sad Girl Theory as rooted in the constantly infantilizing view the patriarchy has on women. She makes an effort to reclaim this word in an empowering manner. It therefore does not literally only apply to young women or teenage girls, but to women and others associating with this theory.

In understanding how women’s individual suffering is linked to larger causes, girls suffering alone in their bedrooms should not feel lonely but hopefully -because of this theory- more understood. Since the artist has chosen to delete her Instagram and, with it, the Sad Girl Theory for reasons that will later become apparent, I have refrained from using screenshots of her old account. Apart from her own crying selfies, the artist has also shared hospital selfies in which she is often accompanied by feminist theory books, ones she brought along for her time spend in waiting rooms. In this sense, both mental and physical health are a part of Wollen’s personal expression of Sad Girl Art. She shares the private and uncomfortable space of the hospital with the world to regain some sort of power and agency. In the reception of her theory, these works are not often mentioned. On this part of her practice, she expanded in Artillerymag:

“Taking selfies in hospital rooms opens up a small bubble of autonomy in a world where I am objectified the most. There, I am undressed in front of strangers who prod and measure, calculate my risks and rates of life, cut me open or sew me closed, and it’s hard not to feel like a rag doll or a mannequin. […] to go and document my body over and over again reminds me that I am still a person, capable of my own performative gestures and my own artistic practice.”

In spreading her theory Wollen became The Feminist Art Star Staging A Revolution on Instagram, as magazines such as Huffpost introduce her practice. It is a bit difficult to trace back what the next imagined step was (if there was one) after having made this theory public. How should Sad Girls find each other other than combing through #sadgirl on Instagram? Instagram was a flawed but suitable format for Wollen because in this way her theory could reach girls and women more easily. She has also spoken about the value of being able to communicate with young women about feminist theory and their experience of girlhood through instagram. Even with lesser follower numbers needed for stardom in 2014, chatting thoughfully with everyone who hopes to reach you through DMs seems like a project that is too ambitious. It also brings too much focus as well as pressure on the individual artist or theorist. At the same time, Sad Girls were forming in communities on other websites.

Tumblr has been an interesting platform for art, feminism, activist groups and queer communities. Sad Girls seemed to have ruled this platform in the early 2010s, aethesticizing pain in wide varieties on the trope. Tumblr may have brought more ways to verbalize or visualize sadness, and was a site on which its users could share their art and words, with the option to remain anonymous. A confessional tone or stream of consciousness diary excerpts could therefore be found on blogs, alongside reblogs of other people’s art, writing and GIFs. So you could find personal accounts of young women trying to feel less lonely, as well as glorification of self-harm and eating disorders on this site. Whereas the latter is clearly harmful, it seems too big of a conclusion to say that platform on which negative emotions are shared makes the blogging platform as a whole risky or dangerous. Feeling misunderstood and not relating to others, as many Tumblr users would describe their experiences, can be serious and heavy but can also take the form of a lighter, rite of passage adolescent state. Tumblr could also be a starting point to be introduced to art, culture or a bit of theory. It was also a comfortable environment, bringing comfort in recognition and feeling less alone by reaching out directly through privately messaging each other. Thus, creating connection in recognition.

Angst and sadness as aesthetic on Tumblr could for example be seen in zoomed in pictures of bruises or teary eyes, cigarette smoke, images of pill bottles, or almost every second of screen-time of Effy in the UK version of Skins immortalized in a black and white GIF. Or, if Effy is too edgy or mysteriously out of reach, the character Cassie from the same series and her floaty loneliness and spacey sadness is perfectly suit to be reblogged too. Seeing more series in this time that address mental health and allow for more complex female characters, a good development (even when this particular series did not present a nuanced view or provided an educational aspect). However, because of reformatting small parts in bite-sized portions (as established, mostly GIFs) these appealing rebloggable bits are seen as possibly having a harmful romanticizing effect.

In 21st Century Media and Female Mental Health: Profitable Vulnerability and Sad Girl Culture (2023) Fredrika Thelandersson studies the Sad Girl across various social media platforms, and characterizes a type of sadness seen on Tumblr more specifically as melancholia, a mood associated to be “creative and inspiring, rather than the debilitating “stuck-ness” associated with depression. There is also an element of pleasure in melancholia.” There is another connotation with this particular state, it being “the driving force of the archetypical tortured genius.” In this sense, feeling deeply may allow for someone to be more artistic, to sensitively look at parts of life differently and enjoy this ‘skill’. Sadness may be for a greater good, providing meaning-making in suffering.

To exemplify the variety of Sad Girl culture at this time, not only Thelandersson, but also Hannah Williams in The Reign Of The Internet Sad Girl Is Over— And That’s A Good Thing names Lana Del Rey as someone who radiated an “overt yet glamorous sadness, this image of mascara smudged perfectly by tears, of a cigarette in a holder held by a delicate yet trembling hand stuck in the cultural consciousness of the decade.” Fittingly, Del Rey was a big hit on Tumblr, her music videos, in GIFs and her image used in collages next to Marina and the Diamonds and Melanie Martinez. But this quote also hints at her larger cultural status. As early as 2012 with the Born to Die album, and Ultraviolence in 2014, her image and status was not located only on Tumblr or the internet, but in wider popular culture. Looking more closely, Del Rey’s suffering as expressed in her songs is directly linked to a romantic partner. Her lyrics are about a sadness felt in abusive relationships, or when waiting on someone until they can commit to you. The singer describes beauty in not giving up in a man who might disappoint you, or being hurt in various ways in the name of love. Therefore she has often been accused of romanticizing abuse, but Del Rey has clarified she is singing about her personal experiences and it should be her right to do so. The image she emitted is a sort of submissive femme fatale, not powerful in its own right but expressing a passive waiting and hoping. This is signified by her songs about being ‘pretty when she cires’.

Overall, Tumblr’s most visible version of the Sad Girl trope was that of tragically beautiful, a suffering that was intriguing instead of pitiful. Also appearing on the website were emo, a more detached or cynical grunge, soft grunge, heroin chic or the quirky unstableness of manic pixie dreamgirls. Another analysis from Profitable Vulnerability and Sad Girl Culture is the sense of irony or detachment that often appears in Tumblr post about sadness if made in meme-format. Thelandersson sees the ironic humor used by Tumblr users as a relief from difficult feelings, not addressing it directly but circling around it. There is a sort of careful approach in vulnerability, balancing it out with some distant removal from the actual feelings.

In 2013, a series of articles talked about Tumblr and internet trends in preparation of the first Tumblr symposium. Authors Alicia Eler and Kate Durbin described the Teen-Girl Tumblr Aesthetic as having “[...] a darker edge, an undermining of the heterosexual male gaze, as well as an ever-present extreme vulnerability.” One artist in particular they name as fitting in the definition of this aesthetic is “Tumblr Queen” Molly Soda, whose practice consists of sharing her life online. A typical work of Soda is situated in her bedroom, making the private sphere public. The most stereotypical image of Soda is perhaps that of her crying in her bedroom, making her a definite Sad Girl Artist. What is notable here is that she is no Tumblr user who is not approaching vulnerability in a careful or detached way, instead going all in.

Soda’s work consists of photographs, videos and GIFs of herself, oftentimes inspired by a 90s net nostalgia aesthetic. She remains inspired by the early Web 2.0 days of the internet, in which she found there to be much creative freedom. Because the camera is always on Soda, this art about a young woman in her bedroom made for other young women scrolling online in their bedrooms, creates a sort of intimacy. “Whether you’ve seen her dancing on her bed, singing to her webcam or crying into it, Molly Soda epitomizes the “girl alone in her bedroom” image that exists in us all.” Ashleigh Kane writes in Dazed in 2015.

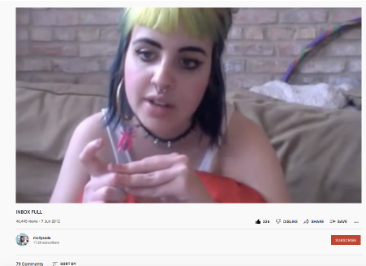

A certain closeness or sense of intimacy is also felt in the comments she receives by posting herself online on her Tumblr. This is best seen in the video piece INBOX FULL (2012), a Youtube video with a duration of over 10 hours1 Just two months ago, INBOX FULL has been acquired by the Centre Pompidou: https://www.centrepompidou.fr/en/recherche?terms=molly%20soda. In this video created because her Tumblr inbox had reached its capacity, Soda reads out all comments or questions she had received on Tumblr, anonymously or not. As far as I can study in her Tumblr archive Soda did not ask people to reach out or offer help or advice to all who request it. These comments directed to Soda must have been posed some time between her first post in 2009 and the production of this video, three years later. This does not seem to fit the medium of Tumblr on which follower numbers were not publicly displayed and the set up of the website was not set on growing accounts constantly. In INBOX FULL Soda goes through the enormous stream of questions and reads them without responding to them, no matter how invasive, offensive or interesting they are. The video is not captured in a single take, there are a few breaks throughout, and we see the artist’s energy levels slowly lowering presumably the first day of filming.

Molly Soda, INBOX FULL (10:09:29), 07/06/2012, posted on Youtube. Screenshot at 1:58:15 and 5:44:50.

Certain comments Soda has received stand out. Even in the first ten minutes, a wide variety of messages can be heard: “Do you get many reactions since you don’t shave your armpits? How do the boys react haha.”How do I get over being lonely / depression?” “I don’t feel sexy or feminine at all, what helps you feel that way?” “What do you think that girls can do about street harassment?” and “Dude, shave your armpits, damn.” Many people reach out to the artist for advice, somehow trusting Soda to hold some sort of answer to their struggles. People who feel different in one way shape or form ask for advice to fit in or to feel more confident. Whereas -alongside other inquisitors- Sad Girls flocked to Soda for advice, she herself does not fit the label in this piece. It takes confidence or at least detachment to read insults without response. Being visibly touched by negative comments would be more fitting to the label, or using this piece to make a statement about harmful judgements on social media. Instead, the general tendency to share and comment online seems to fascinate Soda, both sharing of herself and viewing the sharing others participate in. This does not lead to a moral conclusion, there is just a strong curiosity towards this tendency.

A year after posting INBOX FULL, Molly Soda pushed the boundaries of what is comfortable to share online even further in the publication Should I Send This? (2013). It consists of photographs of the artist, often (semi-)nude, alongside sexts. As the title implies, a reader comes across content the artist was unsure about sending to a possible love or lust interest. Instead of sending them, Soda tried to “purge” herself of thoughts on romance and intimacy, alongside distancing herself from shameful connotations to these feelings. She explains that ideas of this were piling up in her mind as well as on her phone, so this publication was a suitable format for her to place them into. Soda works to discover what is uncomfortable or shameful to share, and why, hoping that in her (over)sharing other girls find some solace and feel less ashamed or alone. In this sense, her work is similar to that of Wollen.

Whereas Soda has never claimed to show an “authentic” version of herself online, or refrained from commenting on whether or not she was performing or presenting a persona, much of the criticism she has received also builds on this idea of whether or not she is genuine or “faking it.” With expectations placed upon her as a sort of helping figure or representation of outcasts, there later arises some anger or disappointment expressed by the art critics and the random public viewing her content when Soda does not carry out this role as they had imagined.

Recently in ⋆。˚ 🌨 。 teardrops on my iphone 。🌩˚。⋆ crying on the internet, Soda looked back at the accumulated collection of her crying online, and writes “Tear-soaked content and the interactions that follow carry a level of absurdity. Perhaps the act of posting oneself crying will always end up lightening the mood.” In earlier interviews she has touched upon going beyond performativity or authenticity, but in this newer piece she clarifies again

“This skepticism of (mostly) girls documenting their sadness feels emblematic of our approach to how we view being online in the first place. Is it real, is it fake, is it attention-seeking? Who cares? Authenticity is an aesthetic, and I’d like to think we are all aware by now that we’re posting for attention, no matter the content.”

Here Soda also lets go of larger judgements, the artist is constantly in the process of documenting and, recently, looking back at her history of documenting. She does acknowledge the camera is a specific sort of mediating tool, and comments are amusing instead of disheartening.

Next to Tumblr, an experimental platform for Sad Girl Art was the online magazine Rookie mag. It ran from 2011 to 2018, uploading articles responding to a monthly theme 3 times a day. Its readers experienced the magazine as a sort of warm and welcome space, one that showed a wide variety of representations of girlhood. It was founded by the fashion blogger Tavi Gevinson, who hoped to create a space in which girls can find a sense of empowerment. Rookie not only welcomed but also promoted a type of alternative (life)style, moving away from the mainstream by encouraging its readers to visit thrift stores, recreate Twiggy make-up or listen to one of their monthly themed playlist to discover old bands. An important difference from mainstream girl glossies was that this online magazine was not build on selling products under the guise of the ability to enhance the confidence and perceived self-worth of teenage girls. Instead of focusing on sharing healthy recipes or more overt tips for weight loss, Rookie would introduce you to tips and tricks like How to Look Like You Weren’t Just Crying in Less Than Five Minutes (03/23/2012). (tagged in their archive only as: #crying).

Serious topics such as substance abuse and sexual trauma were also addressed on this platform, and advice columns were openly discussing mental health issues. Revisiting early articles now, I find the ways in which these topics are introduced to younger readers nuanced and gentle, yet written in a clear tone that does not infantilize the reader. But overall, the wide range of experiences during adolescence, and above all the feelings that are generated alongside them, can have a space to be covered in this magazine.

After a summer of organised meetups of readers and staff in 2012, a report of these meetups ended in the following paragraph.

Rookie mostly avoided making grand statements about its goals, as visible in this text, but here is a hint of a larger sense of purpose. When the magazine acknowledges sadness, it is certain there are ways to be found to fight against it. Collective girl power, the formation of community and understanding the value of girlhood that can coexist with its pains are ways to fight. There is joy to be found in being together (online or otherwise), crafting together, challenging yourself to start writing or photography and enjoying the process; not worrying about being a beginner -a rookie- appreciating the non-aesthetic parts of girlhood.

The prototype reader of this website is not the Sad Girl in essence, more of a Quirky Girl. Emotions and abilities of teenage readers were taken seriously, but a playfulness in dressing up, new versions of playing pretend and making up stories. The Rookie girl’s sadness was not self-destructive. There was an edge in feeling misunderstood, a wallowing in the melodramatic in a less dark way than the melancholia of Tumblr.

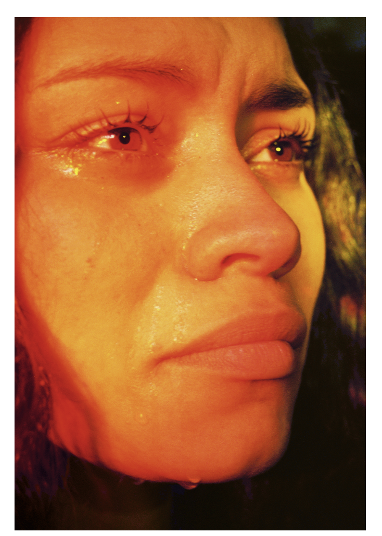

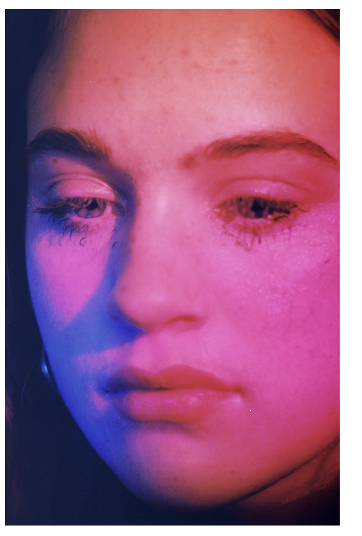

The creative outings on Rookie felt the urgency of girlhood; this was the exact right time to capture this period before it is over, all too soon. The photographs in this online magazine appear nostalgic by default. Moments that had played out only recently already feel far away and forever floating in a dreamy haze. Images from Rookie were often reposted on Tumblr. One particular photograph, by Rookie staff member Petra Collins, would strike a chord on Tumblr in 2014, a prime example of future nostalgia.

Tumblr was a place of inspiration for Collins before she started her own practice. In the early days of her career, she posted portraits of her friends. These intimate portraits, made between 2010 and 2015, have now been collected by the artist in the series The Teenage Gaze. In this series, the everyday lives of these girls is captured, with its ups and downs. There are shots of phone screens on which “mom” appears to be calling, in which it seems likely the call will be ignored. We also see girls chugging beers in the chaos of a party, as well as different settings of girls looking down on landscapes from a roof or staring at the passing landscape from a car. Collins’ friends / models do not smile, they are in a more contemplative state. The setting that most often appears is that of girls getting ready, not in high spirits, instead capturing the insecure moments before going out, or the somewhat anxious checking of one’s appearance once outside. Collins’ early works are dreamy yet serious, and have a sort of film still quality.

In her monograph from 2017, Collins is vulnerable, her upbringing and its struggles summarized in the first few sentences of this publication. She also reflects on her body of work (so far), and concludes that these early works contain a lot of darkness, one she was not always aware of whilst being in it. The camera in her hands seems mystical in this sense, unintentionally capturing her inner state in photographs of her environment, the struggle that surrounded her own girlhood always seeping into the images.

An important series from her career, relating her work not just to the insecure or anxious girl but truly showing Sad Girl Art is 24 Hour Psycho (2016). With these works came one of the first solo exhibitions of Collins. The gallery text describes the works as driven by the motivation “to make space for the young female experience by embracing the historically marginalized subject matter of the complex reality of girlhood”. This confirms the artist’s intention to address mental health more publicly. The “psycho” from the series titles plays with gendered ideas of mental health, specifically questioning female hysteria. In this particular gallery text Collins’ work is directly linked to Wollen’s Sad Girl Theory.

After the popularization of this series (which came out before her monograph) it appears that the photographer has felt more comfortable to speak about her own mental health issues. By doing so she not only relates this series and her practice to normalizing mental health struggles for everyone, but shows her personal motivation to do so. “Agency” is an important reoccurring word in the reception of her works; sadness is allowed to exists, and can feel powerful when fully in control of how one wants to show or process this state. More broadly, expressing these feelings should not place a Sad Girl in a particular undesired category of womanhood as someone who must be doing womanhood wrong. Sadness does not take power away from girls or women, discussing sadness in a more public setting instead gives a more complete view of the full experience of womanhood.

Petra Collins, Untitled #15, #17, #19 (24 Hour Psycho), 2016.

In a recent notable interview, when questioned about the creepy elements visible in her new work, Collins explains this change of focus partially based on her earlier style becoming too recognizable. This is mostly due to the director of the hit series Euphoria allegedly stealing her aesthetic. This has made it more difficult for the photographer to make new work in her familiar style now that it is linked to this particular series, in which her share of the work is not credited. The director of this series, when inviting Collins to collaborate, told her the show was written “based on her photos.” After months of works and on vague grounds, the collaboration was terminated. However, she was not aware that her contribution, the aesthetic, remained, until she saw a poster about the show and “broke down.” Since then, the quote has been deleted from the original article when it started gaining traction online. Similarities between the TV show and the 24 Hour Psycho series are particularly noticeable, and a big part of the cast of Euphoria are models the photographer has worked with before. Arguably Euphoria -a Skins 2.0 for a new generation- was such a hit precisely because of its visual style that made it a compelling coming-of-age story.

The reception of the works of Collins and the other artists seems particularly significant in relation to a certain type of feminism that was visible in the online sphere in the early 2010s. This is because it shows the uncomfortableness surrounding valuing an individual as representative of this movement as a whole. Simply said, within the history of feminism, its continuous blind spot is not considering a wide variety of women in its movement. Current fourth wave feminism is defined by the digital realm and the self-representation of women online. With a broader understanding of intersectionality and critical race theory, there is a slow change within the current feminist movement. However, an earlier hope or idea of the internet as an enormous forum in which feminists hear each other through consciousness-raising practices, is far from reality.

Feminism is proclaimed dead or irrelevant throughout its existence, only to be reborn in a -slightly- different form again. It is no surprise that today there are different opinions on whether the fourth wave exists or if we are in a postfeminist times instead. What is clear is that a decade ago, during the rise of Sad Girl Art, feminism was becoming a popular term again. The ‘90s and early 2000s saw a disdain of the term, instead using de-politicized claims of girl power. In this idea of girl power, structural and societal inequalities did not seem to exist because girls can do anything they set their mind to.

In the 2010s, feminism became a buzzword again. The three studied artists as well as their artistic production are proclaimed to be feminist time and again, without looking at the (historical) implications of this term. There are little claims to be found about on which grounds their works can be considered feminist.

The work of the studied artists is described as powerful and feminist because women’s self-representation is seen to hold this potential. A woman picking up a camera and turning it onto herself is viewed as revolutionary, this narrative is especially seen in the reception of the works of Collins. Out of all artists, Soda has been the most outspoken of the three about being a feminist. She sees a type of joy in women existing online. In her eyes expressing yourself online is powerful and can be considered activist. Being confident or, at least, accepting yourself and becoming more confident and less ashamed, is a process that can be viewed as feminist to her. The newfound confidence can refer to confidence in looks as well as confidently expressing your emotions.

The term cyberfeminist is often echoed when describing Soda”s work, without exploration of the historical meaning of this term. Because body hair is visible in some of her pictures, she is instantly considered a Tumblr feminist. Soda is quite aware of this framing female artist as feminist, without much further analyses of their work, as she has described in Notofu magazine:

“Generally speaking, if you’re a woman making work using your body or strong feminine symbols—your work is going to be called feminist. Once you put a feminist lens over the work in question, people then feel free to project whatever their “feminism” means onto it—whether it’s feminist or not, etc. […] I’ve watched huge comment threads arguing that my work isn’t feminist or that it’s too feminist. Of course I’m a feminist! But can we take a look at the work in question and take it for what it is?”

In Soda’s earlier-mentioned work Should I Send This?, the stream of comments this work received indeed pressured the artist to explain why this work would be considered activist or feminist. Showing yourself (partially) nude with the idea of working towards grander goals of body positivity and self-acceptance was criticized as vain. The relation to other women and the goal of helping them feel more comfortable, the intention of the piece, was not translated to the audience. Of course, Vice’s clickbait title The Cyber Feminist Leaking her Own Nudes does not aid more in-depth discussion in the introduction of Soda as an artist (especially when this is the only time the word “feminist” appears in this article). Instead of feeling the need to defend herself and how her work relates to ideological grounds, the large amount of negative comments on this piece were seen by Soda as reason enough to have made the work in the first place.

Whilst this work and more of her works are in line with messages of body positivity, Soda understands that she -as the sole model in her works- cannot represent a wide variety of women. She also is aware that sexualization and reclaiming agency over one’s sexuality is not only a gendered issue, but a racialized one as well. The artist has created work about censorship of mostly female bodies on social media, but does not describe this as being a feminist issue necessarily. So, as a feminist, and as a woman making work dealing with female issues, not all of the works she produces are definitely feminist, and she urges us to look beyond this label, or ideally dare to zoom in on the label and its connotations.

Looking at the reception of other Sad Girl Artists, Collins, in her early online visibility, was often celebrated as a feminist since she was showing body hair or period blood in her pictures. However, the artist has expressed difficulties with the feminist label precisely because it can be limiting. She is aware that choosing models for her works brings power and responsibility for representation and inclusion.

Collins works with the theme of sexuality, a theme having an especially complex relation to feminism. In her early works she was a teenager, capturing other teenage girls around her. So we can read her work of the time as being self-aware and finding alternatives to a voyeuristic gaze. Or, perhaps, she was just experimenting without much activist thought behind it when posting one of a few upskirt photos she made of her friends. Regarding her early work, she herself has stated that she was not necessarily creating an alternative or female gaze. Similarly, Rookie as a platform has been criticized for showing young women in sexual poses. But this was not intended to be sexual, the young makers were often recreating images they saw in the media. Or, when pictures are consciously addressing sexuality, there was experimental creation in the works of teenage girls testing out what made them feel powerful.

Petra Collins, School Spirit (2011). From: https://www.rookiemag.com/2011/09/school-spirit/

Postfeminism also brings the threat of products being sold under the guise of female empowerment. In the interview Petra Collins on how Tumblr Feminism became corporate capitalism, Ione Gamble (founder of Polyester zine) wrote: “What started as a group of women and queer people – only then teenagers themselves –using their online platforms to muddle through the mess of feminine stereotypes, became moodboard fodder for huge corporations desperate for a new approach to sell products under the guise of empowerment.” Collins is described at someone who defined this fourth wave aesthetic. This refers to her playing with the color pink or using the soft focus and pastel tones, a “dreamy, hyper-feminine” approach to photography exactly because it felt so different and distant from her personal experience of womanhood. On the popularity of this style, an article in High Snobiety reads: “Every time you are sold underwear, mattresses, athletic clothes, skincare, or kombucha with a glowing prism of attractive-yet-relatable models in casual repose, you have, in part, the resounding popularity of Collins’ gauzy portraits of Kim Kardashian and Barbie Ferreira to thank.” But the (hyper)feminine imagery that was used as an aspect of self-discovery, or with some irony in the exaggeration of stereotypes, are aspects that are lost when the aesthetic is used on a large scale by commercial institutions, moving from possible activist to postfeminist. When a message of empowerment is commercialized, it is suggested that confidence can be bought with the right products. Or, in the words of Rosalind Gill, an important theorist of postfeminism: “Crucially, the focus on addressing social injustice by focusing on personal qualities like confidence or resilience is that it is not disruptive: the small, manageable, psychological tweaks – or the right gratitude, “reprogramming” negative thoughts – are capitalism, neoliberalism and patriarchy-friendly.”

Looking again at Wollen, her theory and works aim to rid girl from shame surrounding their feelings, in a similar way Soda hopes to move towards shamelessness. Fittingly, Wollen has made statements similar to Soda’s idea that there is bravery in existence, in visibility. The artist points to the personal as political as one of feminism’s most important slogans, and zooms in on what is ‘too personal’, and why. So, she is thinking about why certain feelings are uncomfortable to express outside of the private sphere, and who exactly is uncomfortable when these issues are made public.

In borrowing phrases from feminist theory or slogans from earlier feminist groups, there remains some confusion in what Wollen fights against. Seeing how feminism and postfeminism were unclear terms expressed online at the time of Sad Girl Theory’s founding, this is not surprising. The artist has clearly fought against the idea of ‘girl power’, explaining that if liking yourself is difficult, feeling and celebrating an abstract girl power is a difficult task. The way towards this end goal of power is unclear for some and results in pressure. Wollen on the difficulty in an overly positive type of feminism in Nylon in 2015:

“Instead of trying to paint a gloss of positivity over girlhood, instead of forcing optimism and self-love down our throats, sticking a Band-Aid on this gaping wound, I think feminism should acknowledge that being a girl in this world is really hard, one of the hardest things there is [...]”

Since, ultimately, the feminist movement acknowledges suffering and is built on addressing inequalities, I would argue Wollen is not working against feminism here, but against postfeminism, against the depoliticized ‘girl power’ that does not relate to society at large. Maybe she would agree in a way after all, since in Huffpost she also argues “If your feminism isn’t painful, you’re not doing it right.”

As described, Wollen tried to push what feminist activism could entail, and tried to use Instagram as a main platform or tool to do so. Sad Girl Theory was intended as some sort of starting point or thought-exercise, the artist was not set on the practical sides of finding solutions but looks at what she calls “playful possibilities” instead in her theory. Part of her reason for removing her theory from Instagram was precisely because “sad girl theory is often understood at its most reductive, instead of as a proposal to open up more spacious discussions about what activism could look like.” as she wrote in her post before deleting her account. Wollen’s theory has been misunderstood as possibly glorying or romanticizing sadness. The artist’s way of posting about her theory has been critiqued as vain or narcissistic, another struggle in feminist self-representation that continuously echoes, not only seen above in the critique on Soda, but in art made by women in general. Without intending to, this young, white woman who is perceived as attractive becoming the icon of Sad Girls alienated a lot of women.

As written by Eileen Mary Holowka, the artist became a leader figure for Sad Girls, based on the celebrity status Wollen gained through magazines promoting her work, “as well as her position as having a body that is considered societally beautiful and sexually acceptable.” This makes the theory “neither intersectional nor inclusive.” Part of the problem lies in the platforms that were promoting Sad Girl Theory and art, platforms that promoted individuals, as well as fourth wave feminism’s general tendency to rely on leading figures. Where I think the problem lies too is in the translation of this experimental theory, constantly shifting between a micro and macro level. Whereas Wollen wants to make girls aware of their suffering being caused by societal structures, she does not expand on naming these structures and injustices, not going much further than “being a girl is (extremely) difficult.” And, again, what feminism urgently needs is naming and acknowledging racial injustice and other socio-economic factors in order for it to have an intersectional perspective. Wollen’s personal issues are political, but not universal in regards to womanhood.

Magazines like Dazed and Vice made Wollen into a universal Sad Girl Icon, without considering the layered-ness of sadness and its different causes. The article Closing the Loop by artist and writer Aria Dean is an early signaling of “selfie feminism” going wrong, becoming exclusive instead of inclusive. Dean names 2013 as the year that brought excitement in terms of imagining Selfie Feminism could become, or in how far selfies could be powerful and activist by being a literal sign of life through which people of color and queer people could show their existence, finding power in being undeniably present. Dean specifically names Collins, Soda and Wollen as Selfie Feminists, alongside Alexandra Marzella and Arvida Byström. She argues that because of the promotion of these artists in popular alternative magazines

“[…] “selfie feminism” has fallen into popular approval and become tailored to normative tastes along the way, now favoring whiteness, slenderness, and all the other qualifications it was initially intended to resist.[...] However digital and radical this brand of feminism is marketed as being, in taking up the mantle of second-wave feminist cinematic and visual theory, selfie feminism most unfortunately takes on its baggage as well. Selfie feminism is guilty of extending the violence and ignorance that plagued its forbears.”

In an article on the Substack Hip To Waste, All Alone in Their White Girl Pain (2020), the author writes about how far from understood they feel when trying to engage with Wollen’s work. They also points to these wider platforms who give space or power only to a specific type of woman: “Legacy publications give white women critics ample space and free, unadulterated reign to write about their taste […] but they exclude women of color from the same cultural production. We don’t get to write about the things we specifically derive pleasure—or pain—from, things that tend to signal a working-class, racialized perspective.” A year later, Sarah Hart wrote in Society’s Obsession with the ‘Sad White Girl’ (2021) “Sadness about not adhering to Western beauty standards, or experiencing discrimination and marginalization in one’s day-to-day life, or not being able to afford healthcare are not facets of the Internet Sad Girl’s woes.” Resembling this, in the aforementioned The Reign Of The Internet Sad Girl Is Over by Hannah Williams: “Nobody wants to like your crying selfie if it’s about how you literally can’t afford to buy food, or if you don’t fit the mold of Western beauty standards. Then you’re just a woman, crying. You’re not part of a movement.”

There is still high aesthetic value in the ways in which Collins and Wollen (but less so Soda) captured crying girls, showcasing either themselves or others. Maybe Sad Girl Art does not break as many boundaries when it is still easily consumable. There is a clear filter in these posts, ultimately one has to look pretty when they cry, still aware of an ever-present gaze of the abstracted anonymous online audience. Some uncomfortable moments are too uncomfortable and a camera lens ready to capture them as they are being processed seems unfitting. Naomi Skwarna writes in her essay on Wollen, Soda and closeness in digital art. “Sadness can be framed as luxury, inaudibly scored by Lana Del Rey. But anxiety shows itself without pleasure, recoiling from what might destroy all that has been carefully built, like the Sad Girl herself. Anxiety deletes its account.”And indeed, trophy Sad Girl Wollen deleted her account when understanding the complexity of her position in the theory she created.

Offline and online Sad Girls live on, through Instagram memes, TikTok and popular culture. There is the phenomenon Billie Eilish, and -fittingly- Collins shooting her for Rolling Stone magazine in 2019. There was talk of a new era for Sad Girl music since 2020, with Mitski becoming a lockdown icon. Around this time it was rumored Fiona Apple banned her music from TikTok because audio fragments of her songs were used in contexts that promote eating disorders, or more generally because it was used for videos aestheticizing female pain. The tension between self-expression and romanticization or glorification of negative feelings that is seen as harmful remains. Later, #BookTok recommends books for a Sad Girl 2022 Summer, with the confessional tone in literature by female authors consistently present in the last few years. More and more books with unlikable female lead characters are recommended. Even big outlets such as Vogue speculate the 2014 Tumblr Girl is making a comeback.

Less easily consumable is a sentiment seen on TikTok about how the suffering does not stop. This time around, people (mostly girls) are recording themselves crying instead of just posting photographs. These videos are accompanied by long texts of the causes of their misery, with a selected depressing audio to go alongside it. Whereas this seems to reach new highs of oversharing, the videos specific link to a (somewhat) viral audio, makes its effect more flat. When clicking on one of these audios to explore more videos, the concern you might feel when viewing the first few TikTok lessens and has more of a hollowing effect when you consume multitudes of the same sort of videos in rapid succession. Making a video and posting it into the online void almost seems as a normalized practice, without any concern about the anonymity of the poster as earlier seen on Tumblr. Anyone has the potential to become a small scale meme, their pain so relatable that you might sent a video of this random girl you come across to a friend. Instead of reaching out to the poster, you relate anonymously. What you can see on TikTok is a range from insecure feelings to sharing sexual assault stories. New trends bring news terms such as Traumacore #TraumaTok, or Trauma-dumping.

An example of a TikTok audio is the text ‘nothing’s new’ repeating whilst young women share how they are still as sad as they were last year, or feel a similar misery to that felt in their childhood.

Apart from confessional videos of actual teenage girls, there is a different sort of Sad Girl meme circling on both Instagram and TikTok, in which the absurd adds another creative layer. In memes or popular terminology at large, we can see the idea of rotting in bed becoming normalized. In specific memes there is a move to the extreme female, with unlikable female characters becoming more popular. TikToks feature these characters staring in the mirror, fixing their hair after a breakdown or having emotional realizations whilst staring at themselves. Here, there are characters from Euphoria, Fleabag or The Queen’s Gambit. There is also a more visible move towards the creepy and grotesque. Video clips featuring Shelly Duval, Mia Goth, Possession or The Exorcist represent a sort of breaking point for women; they have suffered so much that they are now externalizing it, no longer acting socially acceptable, embracing the insanity and disillusionment (of the patriarchy). Instead of being haunted, it is time to haunt others. Images have become short video’s with faster and faster cuts, and a screaming audio fragment makes these TikToks such an intense experience that a next step to more intensity is difficult to imagine. The haunting girl memes also vaguely relate to lived experiences anymore; there is only a nod to the gigantic umbrella term of girlhood causing all this suffering.

A final trending audio to discuss is used over video’s of these new icons over their explosive moments on screen.

@glnnrhee girlhood . #corecore #allamericanbitch #imastar #pearl #twd #femininity #femalerage #edit #femalerageedit #girlhood #euphoria #barbie

In other videos, the lyrics after the screaming, "all the time, I’m grateful all the time, I’m sexy and I’m kind, Im pretty when I cry", cause a change of images on screen. It shows the duality of girlhood, the intense bad moments followed by lighter, pretty ones.

This, for both fictional characters

@willbylers im grateful all the time ☺️ #edits #videostar #film

or alternatively showing moments experienced by young women.

@auroravk #girlhood ❤️

The song this audio is a part of is Olivia Rodrigo’s All American Bitch. A loud screaming id followed by a reassurance that the singer can appear calm. In public, she can resume to holds her angry feelings inside. It shows the effort that can go into appearing calm and content, in playing the role of a good girl. It becomes ironic, playing a game, delivered with a conspiratory smirk that other young women can relate to. Rodrigo’s recent performance of it visualizes this nicely:

In this performance, glass gets broken, cakes stabbed and smeared red cake decoration resembles blood. It is Tumblr-esque. But Rodrigo’s version of being pretty when she cries does not resemble the passive Lana del Rey version. It is performative, self-aware, leaning into anger instead of melancholic stuck-ness. (Currently, Collins is directing many of Rodrigo’s music videos, in a similar way playing with the surreal and creepy, leaving the teenage bedroom behind by lighting it on fire).

These types of songs indicate the Sad Girl still exists, but girls have learned to nod along and keep up appearances. In a sense, the Sad Girl is more widely acknowledged, but the community or activism surrounding the Sad Girl figure has faded to the background. Hopefully, the connections and community that formed naturally on Tumblr or Rookie find new platforms to bloom on again. Acknowledging struggles is not the only step to celebrate, it rather is the start of a healing process. The comfort in ironic or extreme memifications of a constant suffering is only temporary. The power from the early 2010s Sad Girl was rooted in community. Its link to feminism in the manner of celebrating the individual took power away from the trope. Only with a dedication to intersectionality, a willingness to make space for others instead of taking it, an overall consciousness of the past, and a move away from the focus on individuals could the new Sad Girl’s power be linked to feminism’s power again. But this is a gigantic process. For now, letting go of the focus on prettiness when crying should give a first sense of relief.

Reference list

Hester Baer, ‘Redoing feminism: Digital activism, body politics, and neoliberalism’, Feminist media studies 16 (1, 2016), pp. 17-34.

Sarah Burke,‘Crying on Camera: ‘fourth-wave feminism’ and the threat of commodification’, Open Space (May, 2016), https://openspace.sfmoma.org/2016/05/crying-on-camera-fourth-wave-feminism- and-the-threat-of-commodification/.

Petra Collins, Coming of Age, New York: Rizzoli, 2017.

Aria Dean, ‘Closing the loop’, The New Inquiry (March, 2016), https://thenewinquiry.com/closing-the-loop/.

Amy Shields Dobson, Postfeminist Digital Cultures: Femininity, Social Media, and Self- Representation, London: Palgrave Macmillen, 2016.

Alicia Eler and Kate Durbin, ‘The Teen-Girl Tumblr Aesthetic’, Hyperallergic, (March, 2013), https://hyperallergic.com/66038/the-teen-girl-tumblr-aesthetic/.

Aristea Fotopoulou, Feminist Activism and Digital Networks: Between Empowerment and Vulnerability, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

Lauren Fournier, ‘Sick Women, Sad Girls, and Selfie Theory: Autotheory as Contemporary Feminist Practice’, a/b: Auto/Biography Studies 33 (3, 2018), pp. 641-666.

Ione Gamble, Poor Little Sick Girls: A love letter to unacceptable women, London: Dialogue Books, 2022.

Rosalind Gill, ‘The affective, cultural and psychic life of postfeminism: A postfeminist sensibility 10 years on’, European journal of cultural studies 20 (6, 2017), pp. 606-626.

Sarah Hart, ‘Society’s Obsession with the ‘Sad White Girl’’ Slick (October, 2021), https://hbslick.com/3598/features/societys-obsession-with-the-sad-white-girl/.

Hip To Waste, ‘All Alone in Their White Girl Pain’, Substack (2020),

https://hiptowaste.substack.com/p/all-alone-in-their-white-girl-pain.

Eileen Mary Holowka, ‘Between artifice and emotion: the ‘sad girls’ of Instagram’ in Kristin M.S. Bezio (ed.) Leadership, Popular Culture and Social Change, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2018, pp. 183-195.

Jessalynn Keller and Maureen E. Ryan (eds) Emergent Feminisms: Complicating a Postfeminist Media Culture, New York: Routledge, 2018.

Heather Mooney, ‘Sad Girls and Carefree Black Girls: Affect, Race, (Dis)Posession, and Protest’, Women’s Studies Quarterly, 46 (3-4, 2018), pp. 175-194.

Tina Sauerlaender, ‘Reflecting on Life on the Internet: Artistic Webcam Performances from 1997 to 2017’, in Ace Lehner (ed.) Self-Representation in an Expanded Field: From Self-Portraiture to Selfie, Contemporary Art in the Social Media Age, Basel: MPDI, 2021, pp. 117-136.

Hannah Simpson, ‘Petra Collins is Not Your Savior: A Female Gaze’, Public Seminar (2 July, 2018),

https://publicseminar.org/2018/07/petra-collins-is-not-your-savior/.

Naomi Skwarna, ‘Come Close, Go Away’, Canadian Art, 33(4, 2017), pp. 112-116.

Fredrika Thelandersson, 21st Century Media and Female Mental Health: Profitable Vulnerability and Sad Girl Culture, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2023.

Hannah Williams. ‘The Reign Of The Internet Sad Girl Is Over— And That’s A Good Thing’, Medium (August, 2017), https://medium.com/the-establishment/the-reign-of-the-internet-sad-girl-is-over-and-thats-a-good-thing-eb6316f590d9.

***

Jade Poolen is a curator and art historian, currently working as a junior curator at Museum Krona. She is interested in (researching) photography in the digital age and feminism, either as separate subjects or both at the same time.