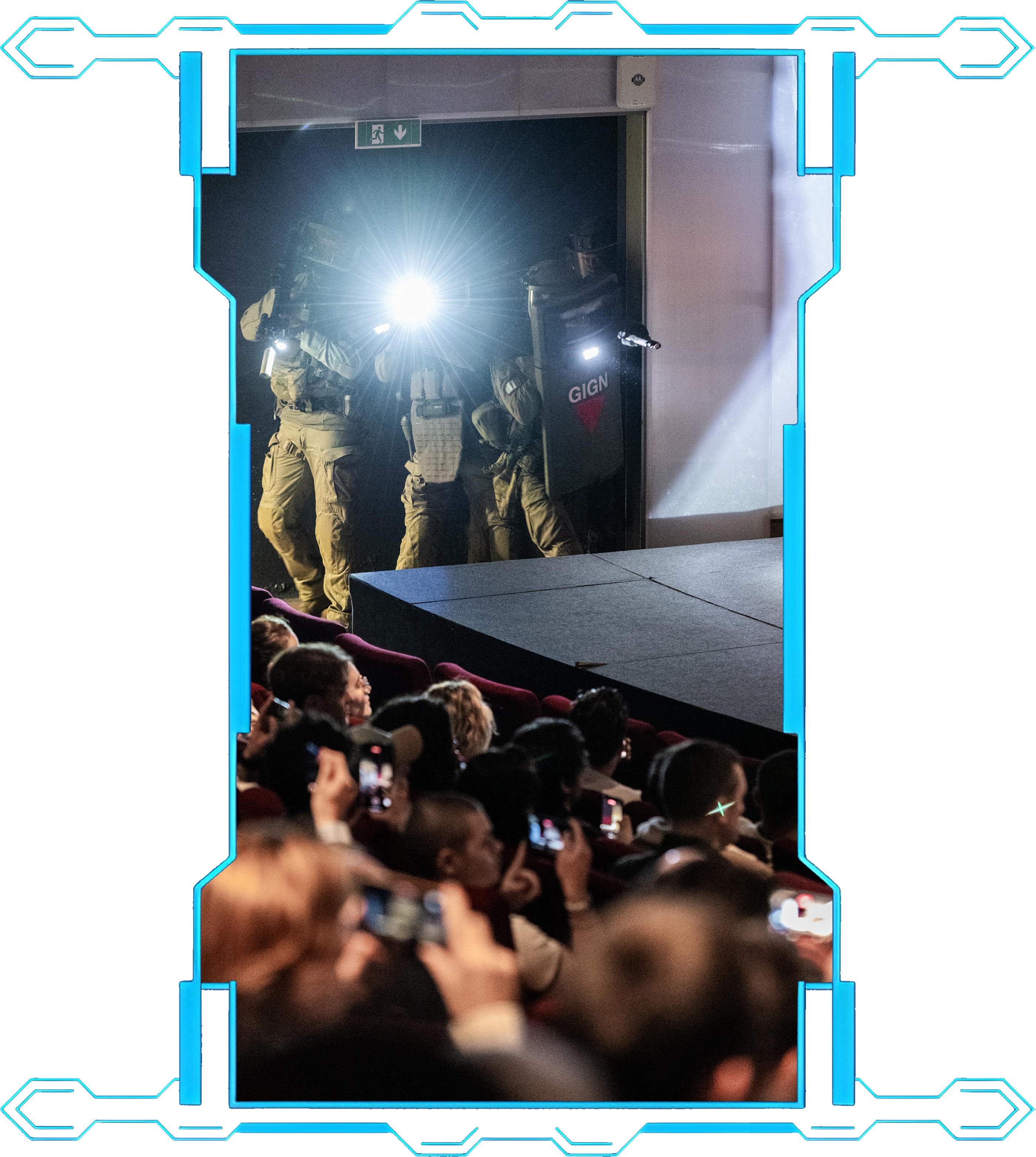

In a crowded room with around a hundred people, two terrorists burst in, rifles raised, declaring everyone inside a hostage. One of them points to a woman nearby, forcing her at gunpoint onto a small stage with her hands over her head. Tense, eerie music fills the space as the terrorists make heated phone calls with what seems to be the police. Then, in an instant, officers storm the room from every entrance, accompanied by drones and police dogs. Gunshots are fired, and the terrorists fall. Just like that, we’re freed.

I wish this was a cut-scene from Call of Duty: Black Ops or a trailer for a new season of 24. I wish this was a theater play critiquing the US never ending war on terror, or a self-organized LARP by some nostalgic veterans. But it wasn’t. This was a real demonstration by the official state forces, staged in a dimly lit theater at Milipol—the world’s largest weapons expo—held in November 2023. If not for the constant hum of French voices in the background, I might have assumed I was on U.S. soil. Few things feel as quintessentially American as a gamified spectacle of violence, aligned with the well-documented military-entertainment complex.1Lenoir, T., & Caldwell, L. (2018). The military-entertainment complex (Vol. 4). Harvard University Press And yet, here I was in France, a nation that publicly upholds the ideals of liberté, égalité, fraternité while quietly positioning itself as the world’s second-largest arms exporter, raking in a record €27 billion in arms deals in 2022 alone. With little to no existing research on the matter, I decided to explore the Parisian manifestation of the global military-industrial-entertainment complex – starting online.

Enlarge

© Milipol Paris 2023 / Anne-Emmanuelle Thion

At first glance, the expo could seem entirely benign, as it was presented on its official website as a “leading event” dedicated to "security and safety" and organized under the patronage of the French state. However, a bit of browsing brought up an array of different controversies. In 2017, Amnesty discovered illegal torture equipment for sale at the expo as well as riot control gear that has repressive regimes for human rights abuses. The expo also showcased companies supplying weapons to the IDF for its devastating assaults on Palestinians, alongside facial recognition firms criticized for deploying their technology at contentious checkpoints in the West Bank. For context: this fair took place only a month after the beginning of Israel’s full-scale invasion of Gaza. I decided I had to see this spectacle with my own eyes.

Of course, this action required some "LARPing" as a corporate arms dealer. This was because, despite being organized under the patronage of the French state, the expo wasn't a public event. It was limited to manufacturers, developers, potential buyers, like government officials and contractors, as well as researchers or journalists who could prove their work's relevance to the sector. I eventually got access as a “researcher” interested in “counter-terrorism”, which allowed them to assume I was there to learn about security strategies, not to critique them. To avoid drawing attention, I therefore left behind anything that might mark me as a socially aware, leftist student and dressed the part instead. I threw on a navy suit, dusted off an old chestnut leather briefcase I used to carry in high school, slicked back my hair to blend in with the professional atmosphere of the expo. By the time I arrived at the Parc des Expositions, just a short train ride from the Eiffel Tower, I was in spy mode, ready to gather intel on war profiteers, violence fetishists, and their corrupt networks.

LEVEL I:THE COMMERCIAL EXPO

When I entered the main hall, I was immediately struck by the grandeur of the event. The vast open space, with its tall ceiling, was filled with a sea of people dressed in suits walking around the islands of exhibitor booths, restaurants and event stages. With 1,116 booths radiating cold white LED lights from every corner and the noise of over 30,000 visitors filling the air, the atmosphere was that of excess, of overstimulation. And there was no escaping it — even in the bathroom, an ad for shooting targets from the French company ZSHOT stared back at me from the stall door.

Enlarge

© Milipol Paris 2023 / Anne-Emmanuelle Thion

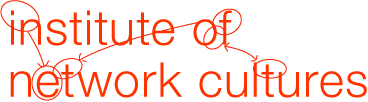

Decadence and Deadly Precision

Back in the main space, my attention was caught by the exhibitor booth of the Israeli company Smartshooter. Their setup was sleek and polished, with flatscreens, LED logos, modern furniture, and a strange life-sized portal shaped like the company logo. At the booth counter, they offered mini pain au chocolat, coffee cakes, and potato chips, all displayed alongside take-home product catalogs with images of what looked like automatic rifles. Around the tables in the booth, I saw men in suits casually discussing business over drinks, while behind them, the company’s fire control systems were neatly mounted on the walls.

The juxtaposition of sleek design, French pastries, and alcohol alongside weapons was a striking, but common sight at Milipol. Nearly every exhibitor booth, regardless of whether they sold drones, surveillance technology, or tactical gear, offered snacks and refreshments like branded candy, soft drinks, and sandwiches. During my time at Milipol and another similar security expo, I also encountered some more extreme examples, such as lavish oyster towers, ergometric-bike-powered smoothie stations, and perhaps the most peculiar sight—a booth with a live DJ set and an open bar, where potential buyers danced amid towering displays of missiles. The marketing at Milipol was therefore not only visual and static, but also deeply atmospheric, operating on the premise that making the purchase of weapons more pleasant, carefree, and fun would increase the likelihood of sales.2Feigenbaum, Anna, and Daniel Weissmann. “Vulnerable Warriors: The Atmospheric Marketing of Military and Policing Equipment before and after 9/11.” Critical Studies on Terrorism 9, no. 3 (2016): 482–498. While this was unsettling enough on its own, what was perhaps even more disturbing—given the pervasive presence of alcohol—was the thought that million-euro weapons deals might be negotiated by drunk company and state representatives. These scenes encapsulated a kind of European decadence, a 2024-version of Cabaret, where the gravitas of deadly arms is overshadowed by an atmosphere of indulgence and hedonism.

Enlarge

I took a closer look at one of Smartshooter’s catalogs to learn about their “flagship” product. They made "SMASH," a fire control system for weapons that uses AI, computer vision, and advanced algorithms to ensure that every shot hits its intended target. Essentially, it is a weapon accessory for automated firing, which also makes it appropriate to remote warfare. The marketing of SMASH leaned into the aesthetics of video games, trivializing violence in a way that felt eerily familiar. The slogan “one shot – one hit” could have been ripped straight from a Call of Duty loading screen, and the company name, Smartshooter, has a playful, almost gamified ring to it. Even the product names—SMASH, Dragon—evoke the stylized weaponry of shooter games like Valorant, where guns have names like "Ghost," "Stinger," and "Vandal." This unsettling framing made me wonder what exactly Smartshooter’s SMASH was “smartly shooting at”. After wading through a lot of technical jargon in the catalogue, it seemed the technology was primarily being used to target small UAS—unmanned drones. Given that the context appeared to focus on defense not offense, this gamified marketing strategy, as well as their claim that the system was “combat-proven,” felt a little tasteless but not overly concerning.

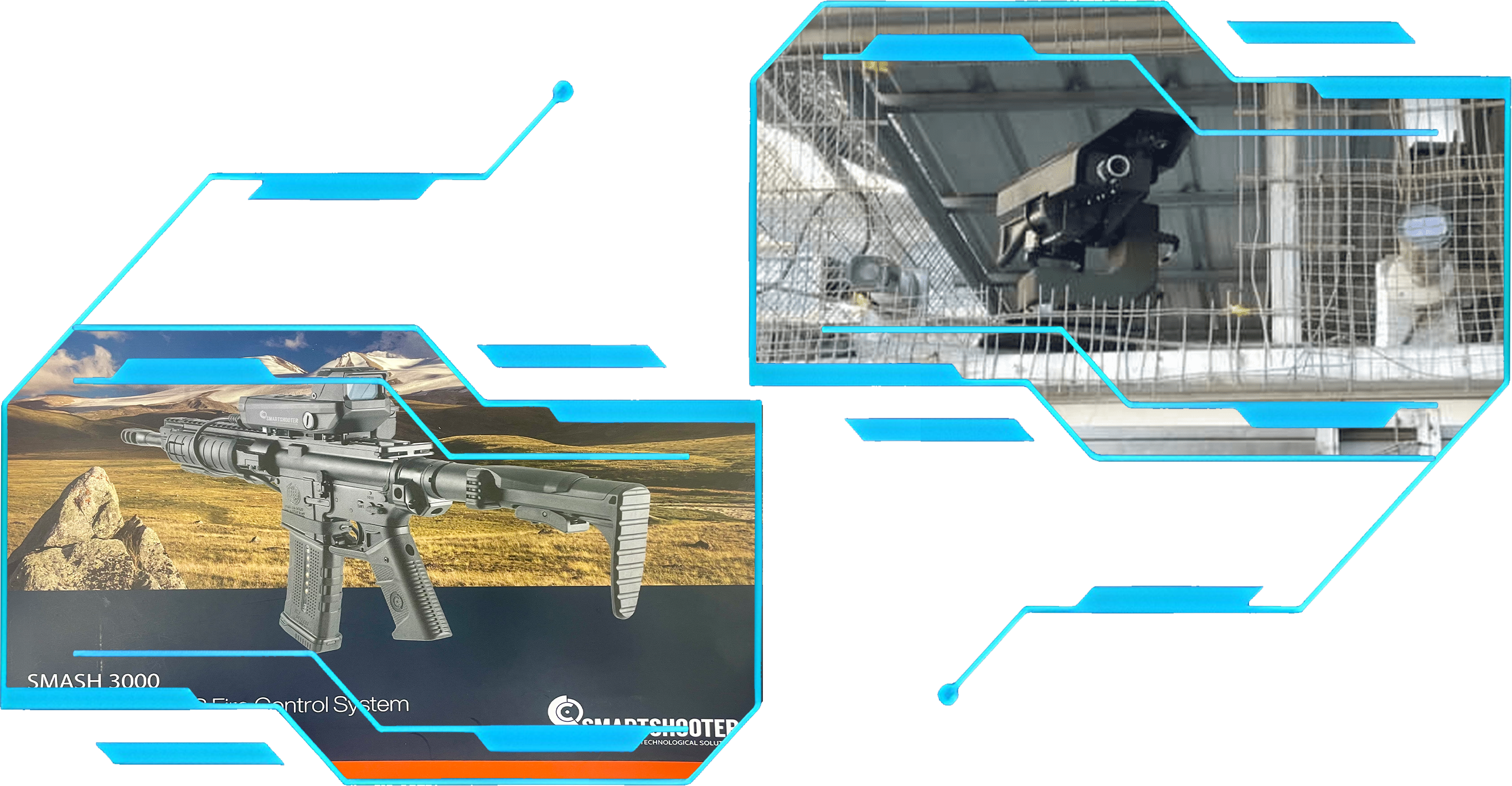

However, when I researched the company further, I discovered that a remote crowd dispersal weapon with the Smartshooter technology has been installed at a checkpoint on al-Shuhada Street in Hebron, Palestine. At this checkpoint, which sees over 200 Palestinians daily, including schoolchildren, Israels Smartshooter powered remote weapon can fire stun grenades, tear gas, and sponge-tipped bullets, at any sign of perceived non-compliance. In the context of this, the video-game-esque marketing of Smartshooters systems, like the slogan “one shot – one hit,” the claim that the system was “combat-proven”, became a repulsive but telling example of the way arms dealers trivialize civilian suffering.

I looked at the Smartshooter pamphlets again and noticed the absurdity of the imagery. The company presents its fire control systems, attached to rifles, floating in mid-air, pointed towards desolate mountain ranges and vast, empty landscapes. These serene backdrops make the weapons appear strangely peaceful, as though they exist in untouched, natural worlds, far removed from war or any human targets. In contrast, images taken by Palestinians in the West Bank of the same weapon systems tell a much different story. One of these photos showed the SMASH system deployed at the checkpoint in Hebron, the aforementioned palestinian city under Israeli occupation. By placing their weapons in such imagined, untouched spaces, companies like Smartshooter obscure the human cost of their technology, erasing the crowded streets, the protests, and the people their systems target. As a result the weapons are aestheticized, allowing them to be enjoyed as beautiful objects despite their inherent violence and purchasing the firing system—like the armies of the Netherlands, India, Germany, and Great Britain have already done—become depoliticized and therefore justified.

Enlarge

Smartshooter, like many other exhibitors, didn’t just rely on aesthetic, sensory-driven marketing; it also capitalized on masculine sexual desire. A striking example of this trend throughout Milipol was the prevalence of young, conventionally attractive women—often dressed in tight dresses and high heels—stationed at various booths. Upon looking into it further, I discovered that many of these women, including one at Smartshooter, weren’t actually employees of the exhibiting companies—they were hired models brought in through modeling agencies. The agency that Smartshooter used was the Czech company VictoryModels, whose website lets you filter for the “perfect model” to help sell your weapon of choice by selecting criteria like weight, size, and hair color. These models reminded me of NPCs in video games: hyper-feminine, perfectly styled, designed to fulfill a scripted, aestheticized role while remaining peripheral to the main action. Just as NPCs in video games appeals to the masculine desires with their scripted cheer or flirtation, these women helped construct a certain sex appeal around the weapons sales and trivialize the technologies on display. Just a month after this model was posing with Smartshooter’s weapon station, it was being used by the Israeli military’s Maglan special forces in the Shati refugee camp in northern Gaza.

For more on the intersection of cutification and violence, check out Noura Tesfache’s essay “The Kawayoku Tales”.

Enlarge

While Smartshooter relied on a straightforward display of products, advertising, and sales-worker, others transformed their booths into miniature spectacles, complete with flashing lights and larger-than-life product installations. French manufacturer IP Mirador showcased a CCTV towers that expanded and contracted like a transformer. Swiss company BDT presented ammunition on a rotating stand reminiscent of a makeup display at Sephora, as well as two gigantic bullets, over two meters tall. French company EMD took a more immersive approach, recreating a war-torn urban landscape with mannequins of soldiers, military gear, and a devastated city backdrop. The way the companies exhibiting at Milipol turned weapons and tactical gear into artistic, aesthetic spectacles made it easy to forget what they were really for. Even I, fully aware that many of these weapons were being used to oppress and kill, found it hard not to respond to the aestheticized displays with a distanced fascination.

Sci-Fi Aesthetics and the Feedback Loop of War and Entertainment

Another booth that caught my eye was that of the Serbian company PR-DC who showcased its IKA-bomber—a sleek, shiny white military drone armed with bombs boasting a blast radius of ten meters. The drone was carefully displayed on a table, and behind it was a massive screen playing an advertising video for the same product. What I found interesting with this video was not its content but a strange sci-fi video game UI that framed it. The green-and-black color palette, glowing borders, and interface elements strongly resembled the neon-heavy, grid-based interface aesthetics of sci-fi video games such as Halo or Mass Effect. Of course, as a video is not interactive, there was no practical reason for a UI to exist. The status bars, in particular, were absurd. Probably, the goal was to approximate the cool, high-tech aura of a sci-fi shooter, and, through that, to present the drones as if they belonged in the depersonalized world of digital combat rather than the messy realities of war.

Enlarge

Digging deeper into the company, I discovered that PR-DC, or Pink Research Development Center, is not an independent defense manufacturer but the R&D branch of Pink Media Group—one of the largest media and entertainment empires in Serbia and the Balkans. Pink Media Group owns a network of TV channels, a film production company, and a radio station, and it has been repeatedly accused of spreading both Russian and Serbian propaganda. In this context, the marketing of drones using video game aesthetics feels strangely on-brand, merging militarization, entertainment, and propaganda into one glossy package. And just as PR-DC’s drones at Milipol borrowed the aesthetics of sci-fi gaming, the entertainment wing mirrors this interplay in reverse. Online I found a poster for the Pink Media awards ceremony September 2024, which featured drone imagery mixed with disco balls, vinyl records, headphones, and retro gaming consoles. The result is a cynical feedback loop: war machines for sale are gamified to appear cool and futuristic, while pop culture adopts the visual language of violent drones.

Enlarge

This reflects a broader trend of the military-entertainment complex, which thrives on the increasingly blurred lines between the military, weapons manufacturers, and entertainment executives. Together, they collaborate to shape both virtual and real-world battlefields,3Mantello, Peter. "Military shooter video games and the ontopolitics of derivative wars and arms culture." American journal of economics and sociology 76.2 (2017): 483-521.

where violence is preemptively justified as necessary for mutually beneficial causes: the military—and, in the case of Milipol, weapons manufacturers—secures cultural consent for its practice and trade of violence through video games, movies, and their associated aesthetics, while game developers and filmmakers gain access to military expertise and technology, improving the realism of their creations. A more well-known example of this symbiosis is Hollywood’s collaborations with the U.S. Department of Defense, which provides filmmakers with access to military equipment, locations, and technical advisors in exchange for script approval. PR-DC’s presence at Milipol underscores that this logic of the military-entertainment complex extends beyond the film and gaming, influencing the marketing of real weapons.

The convergence of war, entertainment, and marketing wasn’t limited to PR-DC. At Hologate’s booth, I saw the company promoted its "high-end extended reality (XR) solutions" for military and law enforcement training with glitchy visuals and heroic, adventure-themed music. Their military simulations, heavily focused on shooting scenarios, were almost indistinguishable from first-person shooter games like Call of Duty or Battlefield. Here, the traces of the military-entertainment complex weren’t just in the marketing—they were embedded in the technology itself. Hologate began as a VR entertainment company before pivoting to use the same systems for real-world military and police training, including training for the Berlin police. Their consumer games include Revolver 3, where players “defeat robot enemies in a dystopian Wild West shootout,” and Mission Sigma, which tasks users with stopping a terrorist from detonating an atomic bomb.

Even more surreal, I came across a Facebook photo of the Ghostbusters: Afterlife cast—including Stranger Things star Finn Wolfhard—playing Ghostbusters VR Academy with Hologate-produced VR weapons. The equipment looked almost identical to the weapons I saw used for military training at Milipol, meaning that fictional heroes and real soldiers alike are “preparing” for combat using the same VR systems. These overlaps between entertainment and military training left me questioning: can the two truly be separated, or is there an inevitable bleed between the virtual worlds of consumer gaming and military prep? If Finn Wolfhard sees ghosts in Hologate’s VR games, what are the “ghosts”—the imagined threats—in its military programs?

These concerns are deeply tied to the logic of preemption, a mindset that underpins both VR gaming and its military counterpart, VR training. Peter Mantello, in his paper “Military Shooter Video Games and the Ontopolitics of Derivative Wars and Arms Culture,” 4Mantello, Peter. "Military shooter video games and the ontopolitics of derivative wars and arms culture." American journal of economics and sociology 76.2 (2017): 483-521.

argues that video games create virtual battlefields where the future is actively constructed—training both gamers and militaries to prepare for dangers that may never materialize. This logic of preemption—central to post-9/11 military operations—functions through what Brian Massumi terms “Ontopower,” where speculative scenarios and ideological biases are disguised as abstract intelligence or actionable data. In the context of VR simulations, this logic isn’t just reproduced; it’s amplified since immersive environments heighten the urgency and certainty of preemptive action. The marketing of Hologate’s simulations makes this logic glaringly clear. Emphasizing split-second decisions to shoot, their materials present these scenarios as critical, even though they’re largely speculative. In Germany, for example, there were only 11 police killings in 2021. Yet by normalizing the "shoot first" mindset in training, these simulations risk embedding preemptive thinking that parallels modern warfare. Both military and gaming contexts reinforce a pervasive, speculative approach to threat prevention, making preemption not just a strategy, but a mindset that shapes real-world practices—often more imaginary than necessary.

Practice Makes Fiction & the Suspension of Disbelief

The marketing at Milipol mirrored video games not only in its spectacle and aestheticization of violence but also through its interactive elements. At Lasershot and Hologate, for instance, potential buyers could take aim at robbers, terrorists, and school shooters with their "toy guns," simulating firearm training in a game-like environment. At other booths of companies, like Corsight and Maris, visitors could watch themselves being surveilled by the latest in facial recognition; in nearly every exhibitor of handheld weapons, from pistols to sniper rifles, encouraged attendees to pick them up and aim into thin air. At the French company Nexstun’s booth, visitors were invited to try a virtual reality (VR) demo of their "electric impulse glove"—a device condemned as illegal by Amnesty International for its association with torture practices—essentially allowing visitors to practice torture.

By allowing this level of interaction, the weapons of violence become tangible, but in a highly mediated way. Not tangible in the sense of understanding what it feels like to live in Gaza, to lose family to bombs, or to witness the destruction of your community. Instead, they become tangible through a gamified lens. The act of holding and aiming a weapon mirrors the mechanics of a first-person shooter, detaching the user from the real-world consequences of pulling the trigger. Carol Cohn’s reflections after visiting the New London Navy Base provide a strong framework for understanding this phenomenon.5Cohn, Carol. "Sex and Death in the Rational World of Defense Intellectuals: Violence in War and Peace." In Violence in War and Peace: An Anthology, edited by Nancy Scheper-Hughes and Philippe I. Bourgois, 467-479. Vol. 5. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2004. Cohn describes how military personnel often “pat” missiles as a gesture that suggests both intimacy and control. She writes:

“For patting is not only an act of sexual intimacy. It is also what one does to babies, small children, the pet dog. One pats that which is small, cute, and harmless — not terrifyingly destructive. Pat it, and its lethality disappears. [...] The imagery can be construed as a deadly serious display of the connections between masculine sexuality and the arms race. At the same time, it can also be heard as a way of minimizing the seriousness of militarist endeavors, of denying their deadly consequences” (359).

This idea of "patting" as a way to make dangerous technologies feel familiar and harmless resonates deeply with what I observed at Milipol. Attendees were not only handling weapons, but affectionately engaging with them as though they were everyday objects, much like the "patting" Cohn describes. In this environment, weapons were stroked and admired, concealing the deadly nature of the technologies on display, transforming them into benign commodities and stripping away the gravity of their true impact.

Enlarge

The reason such a spectacle of violence could unfold so seamlessly lied in the environment Milipol created, one that was sterile, homogeneous, and effectively insulated from external dissent. Secondly, Milipol constructed its own world which followed its own logic. The exhibition map, for instance, mirrored a world map, allowing visitors to explore regions like the "Great Wall of China," "North America," and "Israel," each corresponding to pavilions where companies from those areas showcased their products. The expo leaned into this world-building idea with metaphors like the “First Time Exhibitor Village” and even had its own newspaper and TV station—Milipol Daily and Milipol TV. Milipol Daily offered daily highlights in a traditional newspaper format, complete with “exclusive” interviews and articles, yet the content was jarringly offset by ads for firearms, automatic rifles, and drones. The name "Milipol" itself, likely a blend of "military" and "police," also hinted at something more: the suffix "pol" evoked the idea of a miniature "polis," a self-governing city-state where the rules of engagement, trade, and even culture were shaped by the imperatives of defense.

Enlarge

This world-building approach at the expo closely mirrors the concept of suspension of disbelief in video games. In “On Game Design6Rollings, Andrew and Ernest Adams “On Game Design." New Riders (2003)" Rollings and Adams describe it as a mental state in which players temporarily accept a fictional world as reality, noting that the better a game supports this illusion, the more immersive it becomes—a “holy grail” of game design. Similarly, Milipol’s world-building encouraged attendees to suspend their disbelief, temporarily accepting the sanitized, aestheticized, and commodified presentation of violent technologies. This immersive experience—a kind of gameplay for the security industry—allowed visitors to engage with tools of war as though they were harmless gadgets, distancing them from the brutal realities these technologies inflict globally.

While it was unsettling to experience how the marketing at Milipol aestheticized and gamified violence, this was not entirely unexpected – these were, after all, the products of commercial enterprises, whose only goal is profit maximization. But what about the role of public institutions and states? Surely, I thought, they are more inclined to act on behalf of diverse constituencies and uphold democratic principles like accountability, transparency, and human rights. But this, too, I would have to check out for myself. So I made my way to the special forces demonstration of GIGN—an elite unit of the French Gendarmerie.

lEVEL II: THE STATE DEMONSTRATIONS

The demo took place in a large, dimly lit theater at the expo. Once everyone was seated around the stage, the presenters stepped forward and announced that the room that we were all sitting in was about to be taken hostage. The demonstration began, and it became clear that it was a hybrid presentation, combining live action on stage with an 18-minute video displayed on a screen. The sequence began with the video showing a group of terrorists barging into a space resembling the theater and taking hostages. Simultaneously, in the physical space of the theater, two terrorists entered the stage, brandishing assault rifles at us, and subsequently took a spectator hostage on stage. The video continued, depicting the GIGN special forces as they prepared, planned, and strategized behind the scenes. This buildup led to the climax where the special forces were poised to storm the hostage area. As the video concluded, the special forces in the physical space of the theater executed their plan, entering through various doors, shooting the terrorists by firing real guns and freeing the hostages.

Like watching a movie

Enlarge

The first thing that struck me was how the 18-minute long video felt like watching a movie. Not only because of the cozy cinema-setting, but the video itself was structured with a clear beginning, middle, and end, it followed a coherent narrative arc and various editing techniques, including color grading, cutting, montage, transitions, and visual effects, along with cinematographic methods such as motion stabilization and depth of field manipulation. In the “movie,” there were primarily two types of roles around which the dramaturgy revolved around: the terrorists and the GIGN special forces. The role of the terrorist was consistent with what you would see in any other american thriller movie depicting islamic terrorism; Some were wearing what looked like Palestinian keffiyehs, others were fanatically declaring martyrdom and was suggested to be potential suicide bombers. And in line with the American discursive understanding of Islamic terrorism, they were reduced to caricatures of evil: irrational, senselessly violent, and seemingly motivated only by their religious identity.7Stampnitzky, Lisa. Disciplining terror: How experts invented'terrorism'. Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Watching the scenes unfold, it struck me how little effort was made to explore their motives—there were no demands, no grievances aired, no clear reason for their actions. The Islamic terrorists were further portrayed as evil through the aesthetic choices that surrounded them. Their scenes were bathed in dark shadowy vignettes and a cold bluish tint, a visual language borrowed straight from horror movies, reminding me of horror movies such as Pitchfork (2016), Jackals (2017) and The Exorcist (1973). The soundtrack layered over these moments only deepened the sense of dread—tracks like Giorgio Unleashed from the horror movie Castle Freak (1995) played ominously in the background, as if the hostage scenario were less a military operation and more a battle against supernatural evil.

In stark contrast, the GIGN special forces are portrayed as rational, virtuous and heroic. Their scenes are shot in daylight, with unaltered color and no visual effects, and the scenes are accompanied by epic- and heroic-sounding music from "Must Save Jane," a collective known for their action movie trailer music. The narrative echoes this, with the film primarily showing how special forces move through a process of planning, intelligence gathering, and negotiation, reinforcing their positions as rational and heroic. The aesthetic and narrative divide between the terrorists and special forces constructed a clear dichotomy of good vs. evil, echoing the post-9/11 rhetoric often reproduced in Hollywood cinema, that positions forceful counterterrorism as the only rational response.

24 24 24 24 24 24 24 24 24 24 24 24 24 24 24 24 24 24 24 24 24 24 24 24

The GIGN demonstration didn’t just remind me of any movie—it reminded me specifically of 24, the 2000s U.S. television show about Jack Bauer that I had grown up watching religiously with my parents. Some of these similarities were more conceptual parallels than direct references, such as how both the video and 24 emphasized counter-terrorism and national security, frequently depict hostage scenarios, and open with title screens featuring flickering logos on black backdrops that fade out. But other characteristics were unmistakable. Specifically, the GIGN heavily used split screens throughout as a narrative technique, something 24 is known for pioneering.

The split-screen nods to 24 are so blatant they felt like an official state-approved sequel, just swapping Jack Bauer for French special forces. This is significant because 24 isn’t just a neutral entertainment show—it’s known for its portrayal of counterterrorism in ways that legitimize torture and assassinations,8Nikolaidis, Aristotelis. “Televising Counter Terrorism: Torture, Denial, and Exception in the Case of 24.” Continuum (Mount Lawley, W.A.) 25, no. 2 (2011): 213–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2011.553942. and Erickson, Christian William. “Thematics of Counterterrorism: Comparing 24 and MI-5/Spooks.” Critical Studies on Terrorism 1, no. 3 (2008): 343–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/17539150802515012 reinforce stereotypes of Islamic terrorism,9Van Veeren, Elspeth. “Interrogating 24: Making Sense of US Counter-Terrorism in the Global War on Terrorism.” New Political Science 31, no. 3 (2009): 361–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/07393140903105991 and create a clear good-versus-evil narrative tied to America’s controversial war on terror.10Brereton, Pat, and Eileen Culloty. “Post-9/11 Counterterrorism in Popular Culture: The Spectacle and Reception of The Bourne Ultimatum and 24.” Critical Studies on Terrorism 5, no. 3 (2012): 483–497. https://doi.org/10.1080/17539153.2012.723524 If the special forces were consciously adopting this Hollywood-style depiction, it reflects their willingness to use a contentious, Americanized portrayal of counterterrorism to frame their own operations illustrating “how power operates through a merger of state and corporate forces that seek to control the media through which society experiences itself”.11Evans, Brad, and Henry A. Giroux. Disposable Futures: The Seduction of Violence in the Age of Spectacle. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 2015. https://archive.org/details/disposablefuture0000evan. This reflects a broader trend, perhaps more prevalent in the US, where for instance in June 2007, a U.S. Supreme Court Justice referenced the protagonist Jack Bauer from the show to defend the use of torture in counterterrorism efforts, stating that Bauer “saved hundreds of thousands of lives".12Colin Freeze quoted in Erickson, Christian William. “Thematics of Counterterrorism: Comparing 24 and MI-5/Spooks.” Critical Studies on Terrorism 1, no. 3 (2008): 343–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/17539150802515012.

If we assume that the audience of the demonstration recognized the reference to 24, which I immediately did, the effect is that the GIGN video might inadvertently inherit some of these ethical and ideological criticism associated with the TV show that was just mentioned above. It may have led viewers to conflate the dramatized portrayal with the reality of French special forces, and risks transplanting a distinctly fictionalized and dramatic US-centric representation of counterterrorism onto French soil, thereby justifying militarized counterterrorism solutions.

Enlarge

A more general effect of these entertainment references, as explored by Van Veeren on 24 and real-life counterterrorism efforts, is the creation of a feedback loop “where the ‘real’ influences the ‘fiction,’ and the ‘fiction’ influences the ‘real,’ working iteratively to produce new meanings.”13Van Veeren, Elspeth. “Interrogating 24: Making Sense of US Counter-Terrorism in the Global War on Terrorism.” New Political Science 31, no. 3 (2009): 361–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/07393140903105991. Similarly, the demonstration at Milipol presented special forces as fictionalized, pop-culture versions of themselves, constructing what he terms “a hyperreality of counter-terrorism in the global war on terrorism, which works to normalize (…) violent practices and render them more plausible and commonsensical”.14Van Veeren, Elspeth. “Interrogating 24: Making Sense of US Counter-Terrorism in the Global War on Terrorism.” New Political Science 31, no. 3 (2009): 361–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/07393140903105991. Another effect of this entertainment format is the alteration of the context in which the audience experiences the displayed violence. It shifts the focus away from the violence itself, emphasizing instead the aesthetic presentation of the violent act within the image—the colors, composition, and technique used. Consequently, the image becomes a medium where the violent act is not the focus, but rather the aesthetic qualities of how that act is depicted, allowing for the violence to be an object of entertainment.

What makes this pop-culture portrayal particularly problematic, compared to other forms of media like violent video games and action movies, is the context in which it occurs. The demonstration is part of a state-sponsored commercial expo where the entertainment aspect of violence is used to promote the sale of real weapons and militarized security solutions. As a result, portraying violence as entertainment in this context not only has diffuse, normative effects but also direct, potentially devastating, material consequences. The effect of this blurring of simulation and reality, combined with the portrayal of violence as entertainment to promote real weapons and militarized security solutions, is a normalization and legitimization of violent practices within the context of the global war on terrorism.

Enlarge

By using all of these entertainment references and the format of cinema, it positions the demonstration as part of "the spectacle of violence," as theorized by Giroux and Evans in their book Disposable Futures.15Evans, Brad, and Henry A. Giroux. Disposable Futures: The Seduction of Violence in the Age of Spectacle. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 2015. This is because, just like the spectacle theorized by the Situationists in the 1960s, it operationalizes the consumerist gaze and ingeniously uses the power of the image to turn violence into a marketable commodity. While the violence otherwise "would appear politically oppressive," the demonstration makes the audience tolerate these violent conditions through the particular mediation of violence.16Evans, Brad, and Henry A. Giroux. Disposable Futures: The Seduction of Violence in the Age of Spectacle. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 2015. Therefore, while outwardly educational or promotional, this demonstration embeds within it a form of symbolic warfare that narrows agency to the dictates of the marketplace, presenting violence not as a byproduct of conflict but as entertainment and a necessity that fits within the market logic of commodities. As a result, the demonstration participates in a larger cultural pedagogy that normalizes and justifies state-sanctioned violence, and in the process, the political context effectively becomes erased, and the complex conflicts are reduced to black-and-white narratives.

Like playing a video game

Sensorial submersion as deception

Being at the demonstrations felt a lot like watching a movie—but it also felt like playing a video game. I got this feeling due to its immersive, sense-submerging features: real special forces in authentic combat uniforms; actual weapons being carried; the growls of police dogs; the hum of buzzing drones; and real bullets fired from what appeared to be an assault rifle, filling the air with sharp sounds. In another demonstration by RAID, another special forces unit, a real bomb was detonated by the fictional terrorists, sending shockwaves that could be felt, along with loud explosions, rising smoke, and an overwhelming smell. .

Some literature on the mediation of violence suggests that immersive features, like those I experienced during the demonstrations, can strip away the aesthetic distance and reveal violence’s brutal reality. Arnold Berleant argues that immersion can dissolve the Kantian subject-object separation, and create an "engaged experience" of full bodily involvement which can make violence profoundly appalling rather than abstract - an argument also made by Resmus Breazu.17Berleant, Arnold. "Reflections on the Aesthetics of Violence." Contemporary Aesthetics (Journal Archive) 7 (2019): 7. https://doi.org/10.1080/1753915080251501 Breazu, Remus. “The Aestheticization of Violence in Images.” Philosophia (Ramat Gan) 51, no. 1 (2023): 33–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11406-022-00540-w. Since the demonstration displays "real" violence, or at least more "real" than what is typically shown in a two-dimensional visual image these theories suggest the audience might find it unsettling. However, the audience’s enthusiastic reactions—filming and clapping during the demonstrations—suggest otherwise. It can be argued that there is indeed a difference between an embodied versus distant engagement with violence, however, this difference appears more akin to watching an action movie versus playing a shooter video game. They were immersive and realistic but ultimately misleading, presenting a sanitized version of terrorism and violence through omitting the destruction, suffering, and chaos of actual warfare, as well as a nuanced understanding of terrorists and their motivations. This paradox—being deeply immersive yet detached from reality—made the demonstrations dangerously persuasive.

Enlarge

© Milipol Paris 2023 / Anne-Emmanuelle Thion

Playing the victim

Secondly, in particular the GIGN demonstration felt like playing a video game because we, the audience, were not just passive observers—we were drawn into the demonstration by assuming the roles of hostages. This experience became more immersive due to the palpable sense of danger, with the risk to our safety heightening the perceived stakes. Before the demonstration began, the speaker asked everybody to please remain in their seats because real bullets are going to be fired. This was obviously just a safety measure, but it has the, perhaps, unconscious effect of making our roles as hostages feel more real. Just like real hostages, we could not move from our seats because this could potentially be dangerous, even lethal. This possibility of this lethality were also visually demonstrated in the screened video; one of the hostages who tried to escape was shot by the hostage takers.

By positioning the audience as vulnerable hostages, the demonstration emulated video games, allowing violence to be experienced from an "embedded viewpoint".18Schulzke, Marcus. “The Virtual War on Terror: Counterterrorism Narratives in Video Games.” New Political Science 35, no. 4 (2013): 586–603. https://doi.org/10.1080/07393148.2013.848703 This approach shifted the audience from neutral observers to active participants, weaponizing their role with fictional stakes in the scenario. As a result, we become innocent victims of the terrorists and, ultimately, survivors rescued by the heroic efforts of the special forces. In this way, as Richard Godfrey writes in the context of military-sponsored video games, “imagination is curtailed by a tightly woven and controlled storyline and game world in which activities have been pre-coded and through which the player is steered to predetermined outcomes”.19Godfrey, Richard. “The Politics of Consuming War: Video Games, the Military-Entertainment Complex and the Spectacle of Violence.” Journal of Marketing Management 38, no. 7–8 (2022): 661–682. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2021.1995025

In this “embedded viewpoint” location also matters, reflecting both real and imagined anxieties. Since the audience, acting as hostages, is situated in a theater—a commonplace setting within the civilian sphere and part of daily life—the scenario effectively stirred middle-class social anxieties and presents the threat as ubiquitous.20Rothe, Dawn L., and Victoria E. Collins. “Consent and Consumption of Spectacle Power and Violence.” Critical Sociology 44, no. 1 (2018): 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/0896920515621119 Van Veeren, Elspeth. “Interrogating 24: Making Sense of US Counter-Terrorism in the Global War on Terrorism.” New Political Science 31, no. 3 (2009): 361–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/07393140903105991 However, there are also some more severe implications of embedding the audience as hostages in this theater space. This is due to the resemblance of the hostage scenario to the 2015 terrorist attack at Bataclan, which in the same manner as the demonstration occurred in a Parisian theater, both involved the taking of hostages, Islamic-suggesting terrorists, and potential suicide bombers. This mirroring of a traumatic real-life event not only amplifieed the immersion but also intensified the emotional impact on the audience, making the demonstration not just a spectacle of counterterrorism tactics but a vivid reminder of past atrocities. Therefore, through the participation of the audience as hostages in a mundane setting that reflects real-life atrocities, the state violence and the militarized response are presented as a necessary and justified means to combat terrorism and ensure public safety.

Enlarge

© Milipol Paris 2023 / Anne-Emmanuelle Thion

PART III: GLITCHES IN THE MATRIX

I left the theater, went through the expo hall, and out of the main entrance. There I observed a small but determined group of around 20 protesters holding a banner reading, "Stop Arming Israel," while chanting, “Israel genocide, Milipol complicit.” At that point, I really wished I could join them, but with two days left at Milipol, I had no choice but to stand on the sidelines, feeling deeply ashamed of the Milipol badge hanging heavily around my neck, ashamed of the LARP that had gotten too real.

Despite their relatively small number, the protesters faced an overwhelming police presence, including units like BRAV, known for their excessive use of force. Within minutes, authorities arrested and fined the demonstrators. The irony was inescapable. Inside the expo, special forces staged a fictionalized, video-game-like counter-terrorism scenario, a spectacle meant to dazzle and entertain. Meanwhile, outside, a real-life security operation unfolded, with authorities targeting unarmed protesters rather than confronting the realities of what was being marketed within. Torture devices and other tools of oppression were openly displayed and for sale inside the expo, yet law enforcement’s energy was focused on removing those who dared to question it.

These protests function like glitches in the carefully constructed simulation of security that Milipol presents. Indeed, as I have previously mentioned, Milipol scenarios offered a deeply immersive environment, where a particular vision of security is not only presented but also commodified, emphasizing militarized solutions for global peace. This narrative was preserved and left unchallenged by situating the expo in a sterile, homogeneous environment, effectively insulated from external dissent. Entry into this exclusive milieu was strictly regulated through an accreditation process that restricted attendance to industry insiders, coupled with entrance fees that further limited access. The state-centric nature of the expo and its placement in suburban areas, rendered inaccessible to the general public, reinforced this isolation.

That this sanitized, predominantly male, white environment is "industry-only" would not be as problematic if the consequences of what's happening inside the expo only applied to the industry. This is, however, not the case. Companies marketing and selling weaponry, drones, ammunition, and surveillance tech have far-reaching consequences for global security dynamics, impacting not only military and defense strategies but also civil liberties and privacy rights worldwide. The fact that this expo took place while the detrimental effects of weapon exports are being broadcasted every day through the reporting on Gaza further highlights the disconnect between the polished, controlled narratives presented at these expos and the harsh realities of conflict and its impact on human lives. The protesters therefore challenged the expo's vision of security, and turned the argument upside down, implying that this commodified security world actually makes the world less safe. Like glitches it broke "the surface of the immersion, frustrating its coherence and plenitude".21Ball, James R. "Proximity to Violence: War, Games, Glitch." Reframing Immersive Theatre: The Politics and Pragmatics of Participatory Performance (2016): 229-242.

A moment at the expo encapsulated the strange interplay between reality and simulation: a real police dog barked aggressively at a plush toy dog, provoking laughter from the onlookers. They found it amusing that the dog couldn’t distinguish the fake from the real. Yet, this moment was a mirror—they too were immersed in the hyperreal environment of the expo, believing in the simulation of the security world it projected. Just like the dog, they failed to recognize that what they were engaging with was an elaborate façade, not a reflection of reality but a carefully constructed simulacrum. A Disneyland for middle-aged men.

This text was authored by August Kaasa Sundgaard, an Intern Researcher at the Institute of Network Cultures. He holds a bachelor’s degree in Liberal Arts from Leiden University and is interested in the military-entertainment complex, the aesthetics of violence, and post-internet art. Editorial feedback was provided by Sepp Eckhausen and Geert Lovink.