In Dutch they say 'koop een boot, werk je dood'. In English, they say that b.o.a.t. is the abbreviation of 'bang out another thousand'. In Hungarian, in which I’m native, they don’t say anything, lacking a body of water big enough for an opinion. One of the things that got me into broken world thinking is a 120 years old former sailing ship that I have been maintaining and renovating since about a year ago, along with knowing and working on other boats in the last six years. There's other things that drew me to broken word theory, as you’ll see below, but depending on ships anchored me to the idea that technological objects are much more often broken than not, and that the labor of maintenance and repair is in endlessly back-to-back with constant decay.

In my presentation for the conference MetaForumX, I argued that broken world thinking is the connecting tissue of the different themes I have been working with lately. My presentation, All Computers Are Broken was an invitation to think about crisis and technological objects from this unusual perspective. The theme of the network conference was 'PermaCrises', reflecting on the persistent breakdown of political, societal, and cultural systems. From the perspective of broken world theory, permanent crisis could be considered the default state of being, instead of it being time out of joint.

The world is always breaking; it’s in its nature to break. Broken world thinking asserts that breakdown, dissolution, and change, rather than innovation, development, or design as conventionally practiced and thought about are the key themes and problems facing new media and technology scholarship today.1Steven J. Jackson: Rethinking Repair, in Media Technologies: Essays on Communication, Materiality, and Society, Tarleton Gillespie (ed.) et al., The MIT Press, Cambridge, 2014

We take much less notice of a technological object when it is working seamlessly than when it malfunctions, even though things break all the time – actually, they are much more often broken than not. Steven Jackson, in his essay Rethinking Repair, introduces broken word thinking, the idea that the way we know our technological objects through their functionality is a very limited knowing. It being a tiny part of their lifetime, we should acknowledge and examine them in their brokenness to understand how they operate in and on the world. Jackson directs our focus to the moments that technological objects break, and to the times they are broken. And to understand them, their brokenness is something we should examine, for it is the state when technological objects reveal their character. In media theory, there's a lot of focus on innovation, development and how things are designed and functioning. But Jackson tells us that those same innovatively designed objects are, in a big part of their lives, not functioning at all, and then after a short period of functioning, soon they break down. Remarkably, it is when they break down when we can really learn something about them, and that’s also how the relationship between us and our technological objects really becomes visible.

To repurpose Tolstoy “All working technologies are alike. All broken technologies are broken in their own way.’’2Borrell in Steven J. Jackson: Rethinking Repair, in Media Technologies: Essays on Communication, Materiality, and Society, Tarleton Gillespie (ed.) et al., The MIT Press, Cambridge, 2014

If technological objects are, in the largest parts of their lifetime, not yet, temporarily or permanently not functional, and the down-times of these objects remain unseen to the user’s eye, why is it so? Not only because in these times there is no commercial purpose to fulfill towards the consumer, but also because both the sourcing, production and disposal is more often than not organized along extractivist, exploitative, inhumane and ecologically devastating, racist practices that all enact and reinforce postcolonial power-structures, hidden from the privileged customer’s eye.

Enlarge

To illustrate this, Jackson brings into our field of vision the work of shipbreakers in Chittagong, Bangladesh, photographed by Edward Burtynsky in 2012. The industrial cargo ships broken down in Bangladesh are the flagships of globalized industries and trade. They're cut up to small pieces with handheld torches by people in poverty for whom this work provides a precarious livelihood.

In sharp contrast to the technological conditions surrounding its production), teams of workers armed with nothing more sophisticated than a blowtorch are able to separate, dismantle, and repurpose a ship and its constituent parts in a matter of weeks.3Steven J. Jackson: Rethinking Repair, in Media Technologies: Essays on Communication, Materiality, and Society, Tarleton Gillespie (ed.) et al., The MIT Press, Cambridge, 2014

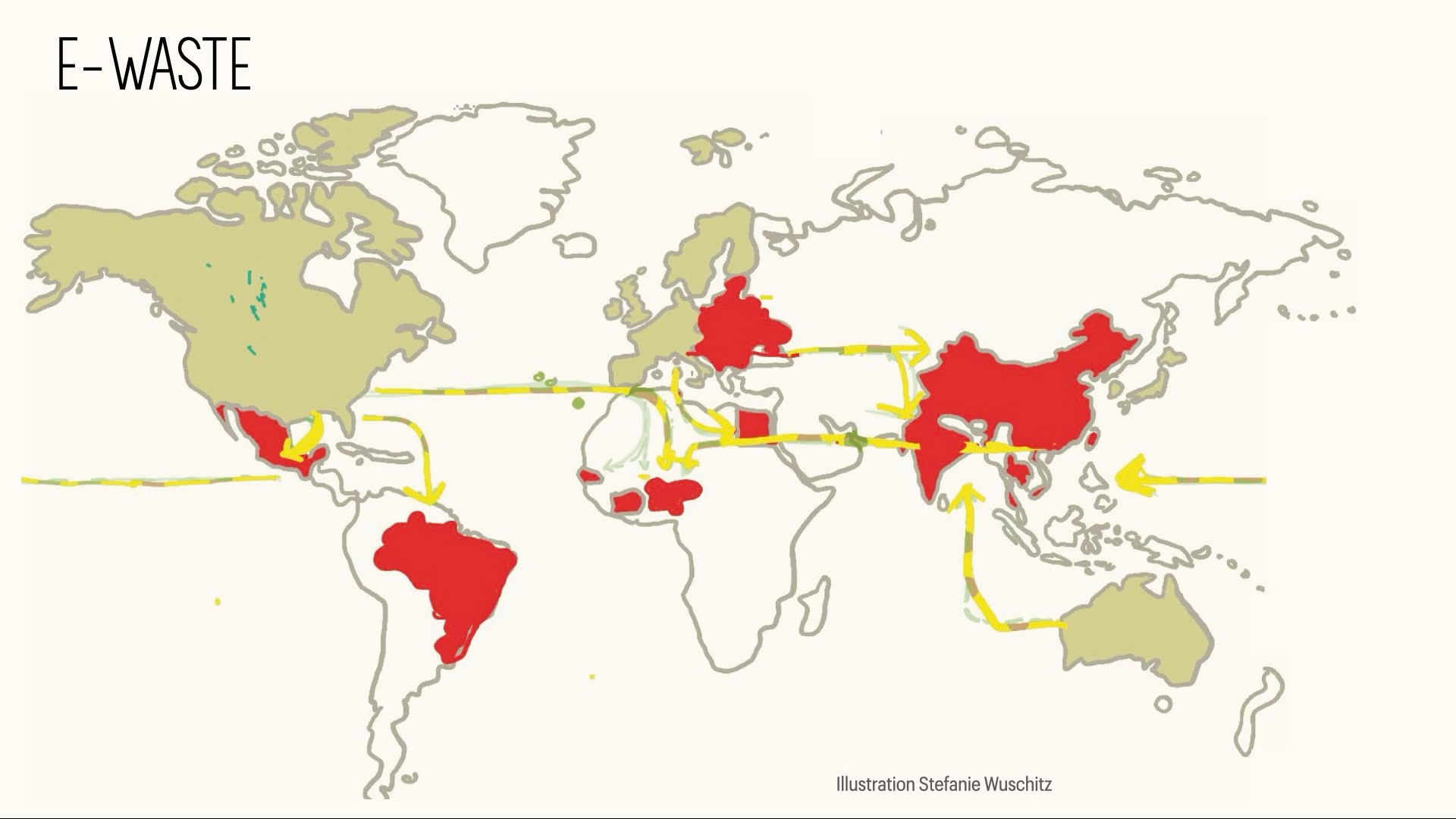

The men do this without any sort of protective equipment. It’s a toxic environment with devastating health consequences. Broken word theory tells us that we don't like to see this happening, not only because we like to know our technological objects only in their state of function, but also because the labor seen here is the type of labor that the Western world doesn't like to do, let alone see or acknowledge. One of the main reasons that our technological objects get disassembled in places and ways we don't see them is that in the places where this happens, there is no account of responsibility that would normally follow in other places such as of fair wages, labor rights, of human rights, of health and environmental issues taken into account. Simply put, it is cheap. A very similar but better known such issue is the case of dumping electronic waste.

To be disassembled and repurposed free of the responsibilities and entanglements that would necessarily follow in other places […] Such work is rendered invisible under our normal modes of picturing and theorizing technology.4Steven J. Jackson: Rethinking Repair, in Media Technologies: Essays on Communication, Materiality, and Society, Tarleton Gillespie (ed.) et al., The MIT Press, Cambridge, 2014

Enlarge

E-waste gets shipped as industrial cargo to regulatory grey zones. Previously to China, now more often to Africa. The recurring waste shipments are beyond mind blowing in scale. The waste is disassembled by hand tools, without protection, without salaries, by people who are caught up in very precarious livelihoods and who take apart and sell the precious metals from the never ending mountains of e-waste. Broken world theory helps us ask the question jf this is labor in the way we usually think about it, and whether this is skilled labor, and whether the people who do this are specialized skilled laborers, while they're not employed and protected the way skilled laborers are protected in the privileged world.

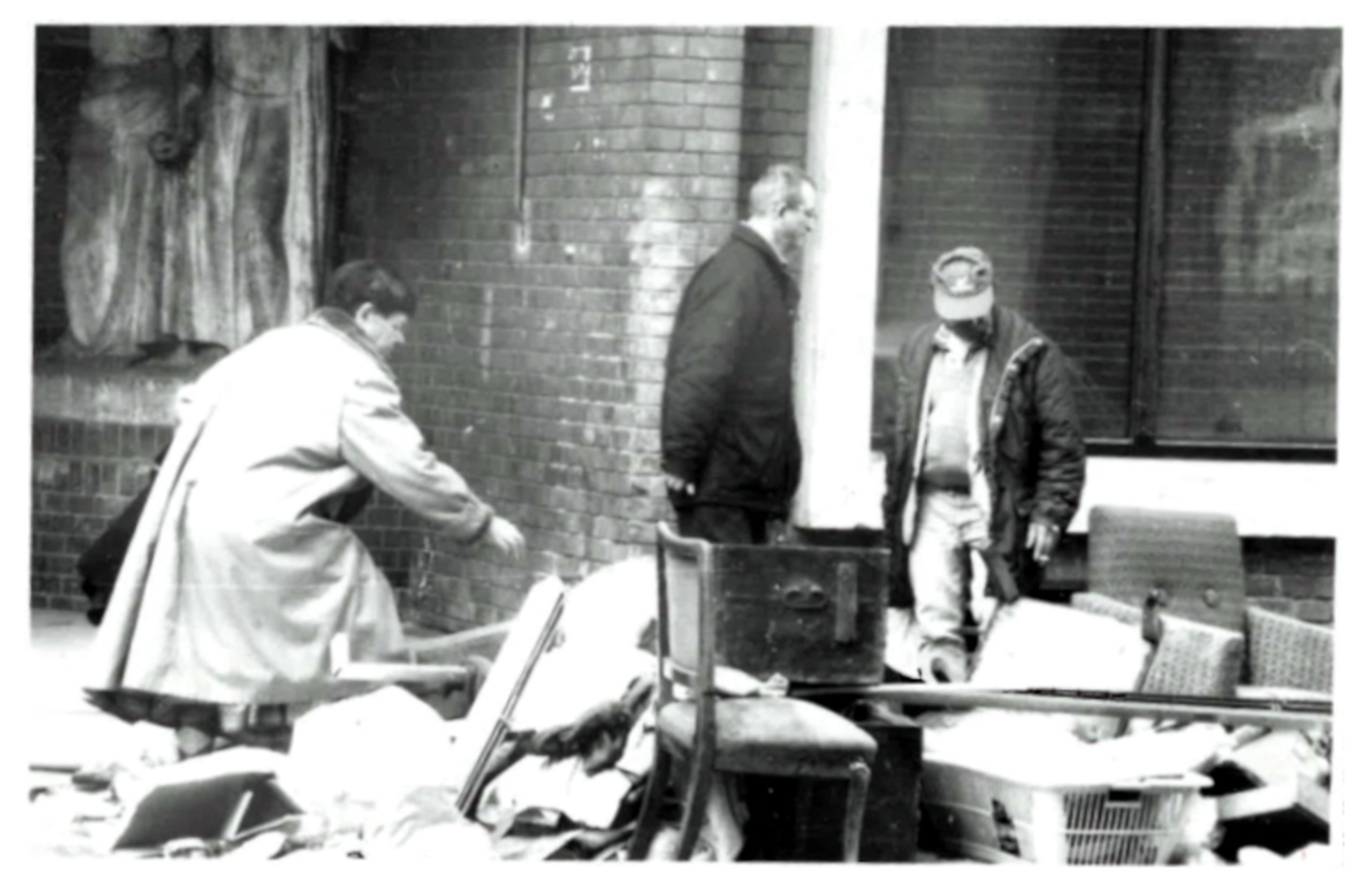

Enlarge

The e-waste scavengers who reclaim precious metals, often under horrendous and unregulated conditions, from processors, monitors, printers, and cell phones in landfills around the world.5Steven J. Jackson: Rethinking Repair, in Media Technologies: Essays on Communication, Materiality, and Society, Tarleton Gillespie (ed.) et al., The MIT Press, Cambridge, 2014

Enlarge

When an old rusty cargo ship or e-waste travels from the US or Western Europe to Mexico, Ghana or India, then the people who produce it don't see what happens with it, because, thanks to it being an operation of changing scales, it's very far – it’s out of range. In the second part of this text, I examine a particular scavenging practice that can help us better understand the sending and the receiving end of waste colonialism, and its sharp contrast with Western conceptualization of sustainability.

‘lomi’

The Global North invests into visions of sustainability towards the future from the present with systematic, conscious consideration. The Majority World, on the other hand, cannot afford to premeditate such long-term goals, but tries to solve present problems, including using available waste as material, in lack of better resources. Between these extremes of strategy move source materials extracted from the latter, and waste exported back to it from the former. Both extraction and waste disposal comes with devastating ecological and societal consequences for the Majority World, while the Global North profits from them. This double process of profiting avoids the acknowledgment of a full legal supply chain and enables the continued rhetoric of valuing sustainability from the North.

These extremes are both in motion simultaneously within Hungary, through the culture of lomi. Lomtalanítás and lomi are not really covered by the English translation ‘house clearance’. It is rather a neighborhood junk clearance, once a year, when whole neighborhoods, hundreds of households all simultaneously, are allowed to dispose of their bulky waste on the street to be later collected by the municipality. Lomi is the practice of going over that waste the night before the collection and picking out useful things from the bulk, a practice widely common in all places where lomtalanítás happens – which are typically former Eastern-bloc countries. I will sometimes refer to the people involved in the activities of lomi as rummagers in this text, while it is important to note that rummaging covers a wider range of activities than lomi, which is a specific set of actions within a specific context. Lomi, for those living in Budapest (and thus mostly involved with the dumping, not the scavenging side), is completely common, even usual and boring, to the level of it being invisible. The public opinion towards lomtalanítás is that of a mix. There is relief, being able to get rid of all sorts of waste easily, if not fully legally, at least anonymously. This is mixed with a hostility towards both the discomfort caused by the presence of waste and that of the rummagers.

Lomtalanítás always fascinated me for its upturning of the cityscape and its social relations. What gets disposed of differs neighborhood by neighborhood. In the type of not-so-well-off neighborhoods where I grew up, the volume of waste is so huge (and its value so low) each year that it is impossible to imagine that the small flats in the houses can ever hold so much trash over the years to spit out. That is partly true- the lomtalanítás has a cascading schedule over the city, so that only one district is paralized at any given time. Therefore people who renovate somewhere else, routinely drop their trash on the actual pile overnight at another district. This is not legal, just like the scavenging of the waste itself.

Enlarge

More importantly, for the 50 years that it exists, lomtalanítás serves as a (partial) livelihood for people in poverty, and in particular for Roma people in extreme poverty. They select, transport, and sell the waste by category to several parties (recycler companies, village markets, etc). This pattern is somewhat similar to the process of high-GDP countries dumping their tonnes of toxic (eg. electronic) waste in low-GDP countries via gray-zone, semi-legal methods, where the poor populations of the victim countries tolerate, select, burn, and sell the waste, lacking safer methods of survival. The global e-waste supply chain and lomi share deep similarities but are in some ways different.

Lomi happens on a much smaller scale. It is extremely social, in the sense that rummagers claim, guard, bargain over and sometimes immediately sell their findings. They work in small groups, often organized along lines of immediate family. Importantly, lomi is ephemeral at any location, but keeps happening at different locations, so there is never a permanent site of collecting, and the small family teams are always on the move. Lomi is technically illegal, but not prosecuted, so it operates in its own grey zone. Residents of any neighborhood where lomtalanítás is taking place exhibit a mix of hostile, friendly and neutral attitudes towards the rummagers.

Lomi is similar to the global e-waste supply chain in the sense that the waste materials on the move are the exact same. Copper, aluminum, steel, lead, and precious metals extracted from printed circuit boards are the most valuable in both cases, while wood is burned for heat, and usable objects and tools can be resold or repaired for own use.

Enlarge

This once a year junk clearance organized by the municipality is a particular moment in terms of a broken world angle becoming visible. When e-waste travels from the US or Western Europe to China or to Agbobloshi in Ghana, the people who produce it don't see what happens to it because it's too far. The distance is out of range. But when we have the lomtalanítás in Budapest, the scavenging, the rummaging, the culture and the labor happens right in front of our eyes. This is one-of-a-kind In terms of Central Europe's position in relation to the concept of sustainability, because its position is in the middle of a scale where different values mix together, and that doesn’t happen without friction.

As mentioned above, West-bound from Central Europe, there's a forward thinking approach advertised: here I am in the present, I look into the future, I acknowledge certain consequences of possible behaviors and I take action to avoid those certain dangers with a forward thinking investment into the future. Often these approaches are systematic and institutionalized. Whereas lomi people, just like those who scavenge e-waste and disassemble cargo ships with handtools, cannot afford a forward thinking approach, nor an institutional one. They are reacting to present needs with present tools directly and personally, and they cannot consider the consequences of their actions in a broad perspective, being the subject of others’ actions. But with lomi, the rummaging and the precarity becomes visible because of the people who scavenge this waste. A huge majority of them are Roma from small villages, coming from extreme poverty. Except for lomi, they do not travel to Budapest. The trash of the capital’s residents being picked by poor people of color from afar becomes very common if you grew up with it. But it really is breathtaking because it repeats the same pattern that the rich white west enforces on the rest of the world, becoming visible on a local micro scale.

The precariousness of lomi is very similar to the precariousness of the people in Agbobloshi. There's a lot of skill that goes into their work, but the people I interviewed in Budapest in 2022 don't see themselves as laborers. They don't see themselves as skilled. They see themselves as people who do something for survival. In order to understand this better, Anna Tsing’s work will be of help. She deploys innovative anthropological research methods in her book The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins.6Anna Löwenhaupt Tsing: The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins, Princeton University Press, 2015 In her network of case studies she examines patterns of precarious survival that characterize the pickers of matsutake mushroom that grows freely in the forests of Oregon, North America.

Tsing points out that Matsutake mushrooms thrive in damaged forests and they do so temporarily – a relevant perspective in response to a permanent stack of crises. Her research looks at the survival strategies of both the wild mushrooms and the people who survive harvesting them in public forests, to teach us something about how can we live together in a broken world.

Enlarge

Ephemeral just like the matsutake pickers, lomi operates an informal economy with unwritten but solid rules. These are value-creating labor processes that cannot really be considered work in the capitalist sense of the word, even if they create a livelihood for the participants. The work, knowledge and the experience of lomi, just like the work and knowledge of the matsutake pickers, is mostly invisible, and the people who do it do not define it as work and knowledge or as a profession. Both processes take place in public spaces, yet they generate private income through the effort invested in finding, selecting, transporting, and selling what is found. In both cases, the material that later becomes valuable is collected in wild, uncontrolled conditions, one in forests, the other in urban areas. In both situations, the amount of value produced from the amount of invested work is relatively unpredictable.

Enlarge

Tsing observes that, because of these aspects, matsutake picking cannot fit into the familiar design and analysis categories of capitalism and cannot be described in a well-rounded way. It is much more unpredictable, assemblage-like and temporal, and the dictionary of the capitalist world order, such as rationalization and scalability, fail to describe it.

Enlarge

Enlarge

Ephemeral just like the matsutake pickers, lomi operates an informal economy with unwritten but solid rules. These are value-creating labor processes that cannot really be considered work in the capitalist sense of the word, even if they create a livelihood for the participants. The work, knowledge and the experience of lomi, just like the work and knowledge of the matsutake pickers, is mostly invisible, and the people who do it do not define it as work and knowledge or as a profession. Both processes take place in public spaces, yet they generate private income through the effort invested in finding, selecting, transporting, and selling what is found. In both cases, the material that later becomes valuable is collected in wild, uncontrolled conditions, one in forests, the other in urban areas. In both situations, the amount of value produced from the amount of invested work is relatively unpredictable.

Tsing observes that, because of these aspects, matsutake picking cannot fit into the familiar design and analysis categories of capitalism and cannot be described in a well-rounded way. It is much more unpredictable, assemblage-like and temporal, and the dictionary of the capitalist world order, such as rationalization and scalability, fail to describe it.

Outlook

Wee see from the above that within and beyond ecological racism, repair and maintenance labor is almost always underpaid or unpaid, while work towards the perception of innovation and progress is highly appreciated. When we look at Jackson’s marveling at the lack of broken world theory labor research, we might wonder why he does not credit feminist critiques of reproductive labor whose history goes back to more than half a century. Not only that: people who build communication infrastructure have studied invisible repair and maintenance for decades. I hereby cherrypick a few which are relevant to the context of MetaForumX. What follows then are a few examples to open up our thinking about labor in broken world terms.

Ruth Swarz Cowan’s More work for Mother investigates the relations of technological change and household labor.7Ruth Schwartz-Cowan: More Work for Mother, The Ironies of Household Technology from the Open Heath to the Microwave, Basic Books inc. Publishers, New York, 1983 It is a great resource to understand how societal changes triggered by industrialization and household technologies alter (or not) the labor conditions in the household. Her research examines North America from the pioneers to the sixties. With industrialization, men swapped working in and around the house to working in factories, while boys swapped it with going to school. In spite of the commercial framing of progress in household technologies, women spent no less time working at home, while cleanliness standards became higher and higher. While men labored visibly and collectively, women’s work stayed behind private doors.

Katja Praznik’s Art Work, then, looks at how unremunerated household work is perceived very similarly to unpaid work in the art world, especially in a post socialist context, and how both are perceived as a labor of love and thus needing no remuneration.8Katja Praznik: Art Work: Invisible Labour and the Legacy of Yugoslav Socialism, University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 2021 This closely relates to Lisa Nakamura’s Indigenous Circuits where she looks at Navajo women who were assembling microchips in the seventies for Fairchild Semiconductor.9Lisa Nakamura: Indigenous Circuits: Navajo Women and the Racialization of Early Electronic Manufacture in American Quarterly, Johns Hopkins University Press, Volume 66, Number 4, December 2014 Fairchild supported studies that revealed how the indigenous craftwork of Navajo women is so similar to how the PCBs are built, claiming that assembling them is basically a form of self fulfillment and folk art-making for them.

While Jackson acknowledges that 'the work of the Wikipedia editors, crafting, honing, and maintaining entries against error, ambiguity, and vandalism', he does not look further into the remarkable context of technological activisms. Autistici is an Italian hacktivist group that was very active in the early 2000s. In the introduction to the book about Autistici, Maxigas points out that infrastructural labor that goes into technological activism is most of the time not publicly visible. However, it is just as much history-making labor as the labor that Anonymous did or the labor that many other more visible collectives do. For instance, the maintenance of servers, of communication channels, and internet connections and so on is just as important for technological activisms as the more visible or more appreciated labor. As Maxigas demands:

It is necessary to rethink the history of technological resistance from a use-centric point of view in order to counterbalance innovation-centric narratives.10Preface to +KAOS. TEN YEARS OF HACKING AND MEDIA ACTIVISM, Institute of Network Cultures, English Edition, Amsterdam, 2017

In conclusion, broken world theory offers the connection between the different themes in my work. It also helps to put into perspective the unjust and vulnerable material conditions that are sustained by the dominance of the violent technosphere that we inhabit. But more importantly, brokenness reveals the cracks where the light comes in – how resilience and survival might be possible beyond that violence.

Juli Laczkó is an intermedia artist engaged with critical research in visual arts and digital culture. She holds a practice-based doctoral degree from the Hungarian University of Fine Arts for her research on visual art and hacker culture. A monograph based on her doctoral dissertation titled The Art of Hacking: Strategic Interactions between Hacker Culture and Visual Arts was published in 2021. Her practice is informed by critical making, social divides, anti-patriarchal, feminist and post-Anthropocentric perspectives, articulating intermediality in space. Works of her hybrid practice of the material and the digital appeared internationally from Leipzig, Vienna, Budapest, Zagreb, Bratislava to Istanbul and the Nevada Desert in collective and solo exhibitions. She lives in Amsterdam and teaches at the Image and Media Technology program at the Hogeschool voor de Kunsten Utrecht.