From the moment I was invited to be one of the speakers at MetaForumX, dedicated to the theme of permacrises, I was certain that the starting point of my presentation would be Amalia Ulman’s 2015 Instagram performance Excellences and Perfections; a work that captured my attention years ago, and what proved to be a recurring inspiration source for my research concerning the effects of attention economy and digital culture on contemporary art.1Read more about the conference here: https://networkcultures.org/void/2024/11/29/metaforum-x-permacrises-repository/. In the summer of 2024, I was considering the idea to comment on the current state of online girlhood but in those weeks a scandal starting out from a Hungarian subreddit (now referred to as Motherless scandal) blew up and shattered the Hungarian online public, and consequently also changed the focus of my presentation. So this essay still builds on the legacy of Amalia Ulman’s groundbreaking work but also ponders on those feelings this scandal brought to surface: the anxieties that derive from losing agency over our online representation; about how gloomy it has become to be present on social media these days; and last but not least: how unchained audiences (both online and offline) have become.

I must start with a personal observation, a confession even: whenever a notification pops up that someone started following me on Instagram, it instantly raises a question in my mind: what made this person decide that they want me to be a part of their feed, and hence, their stream of consciousness? What do people in general expect from my account? On these occasions, for a couple of minutes, I get preoccupied with a weird feeling: the pressure that I have to perform for these followers and their expectations of me, which instantly pushes me to reevaluate my posting habits. Are these people interested in my work? Then they’re most probably not interested in the goofy photos of my dog, even though they give me immense joy to share. Or were they my high school classmates that I haven’t spoken to in years? Then I highly doubt they are curious about my newest academic publications, even though I’m extremely proud of them. These mental spirals that follow the same pattern every single time usually don’t last very long before I come to my senses, because, goodness me, I’m not willing to maintain separate professional and personal Instagram accounts. As Kimberly "Sweet Brown" Wilkins, the mother of viral YouTube videos wisely said: Ain't Nobody Got Time for That.

When I tried to dig deep and reflect on what drives these emotions, I found that the following phenomena are the most obvious sources of my anxiety:

- Online follower bases have become more and more judgy and unpredictable, meaning that any, seemingly harmless post can trigger massive misunderstanding or backlash, and result in being cancelled.

- Not independent from the first point, I – and of course, a lot of other extremely online people – feel more and more protective of our personal sphere and privacy.

- That being said, I – and of course, a lot of other extremely online people – still don’t want to miss out on shouting our most important achievements, happy moments and news into this void.

- And yes, these emotions and needs are absolutely conflicting with each other.

A solution many people choose is to set their Instagram page private; a path I also walked for a short while before the expectations of online personal branding ended my peace. As a curator, I was frequently encouraged to share the documentation of my work and projects publicly so it could reach a wider audience. But then again, I didn’t want to give up on sharing certain bits of my personal life, either, as they are also an integral part of my everyday existence. So I – and of course, a lot of other extremely online people – now need to learn to live with these anxiety spirals.

Amalia Ulman: Excellences and Perfections

What I just described is of course not a new phenomenon. Nothing proves it more than the fact that Amalia Ulman’s Instagram performance, Excellences and Perfections were conceived from the very same anxieties more than ten years ago.

In 2013, Ulman already felt those pressures of Instagram what we now call personal branding: that how we present ourselves on social media plays a huge role in how we’re perceived not just by our friends and family, but also (and mostly) by our potential employers – in the case of artists, by curators, gallerists and other potential collaborators. As she regularly engaged with social media platforms in her work, she was often invited to participate in panel discussions concerning the role social media plays in contemporary art. Reflecting on this period, she later on said:

In December 2013, I was invited to participate in a talk on self-branding. The term nauseated me. Was I self-branding? My openness had become a commercial strategy. No filter. I was unintentionally performing the stereotype of the artsy brunette, the poor female artist that had moved from a provincial town to the big city, the eager learner that requires to be saved by the male director of some museum or some school of fine arts. So if self-representation was an asset, if Facebook selfies overshadowed works of art themselves, I'd have to boycott myself to undermine the capitalist undertone of my online presence. Let the trolls in.2Do You Follow? Art In Circulation 3. London, October 17, 2014. Featuring Hannah Black, Derica Shields, Amalia Ulman. Transcript: https://rhizome.org/editorial/2014/oct/28/transcript-do-you-follow-panel-three.

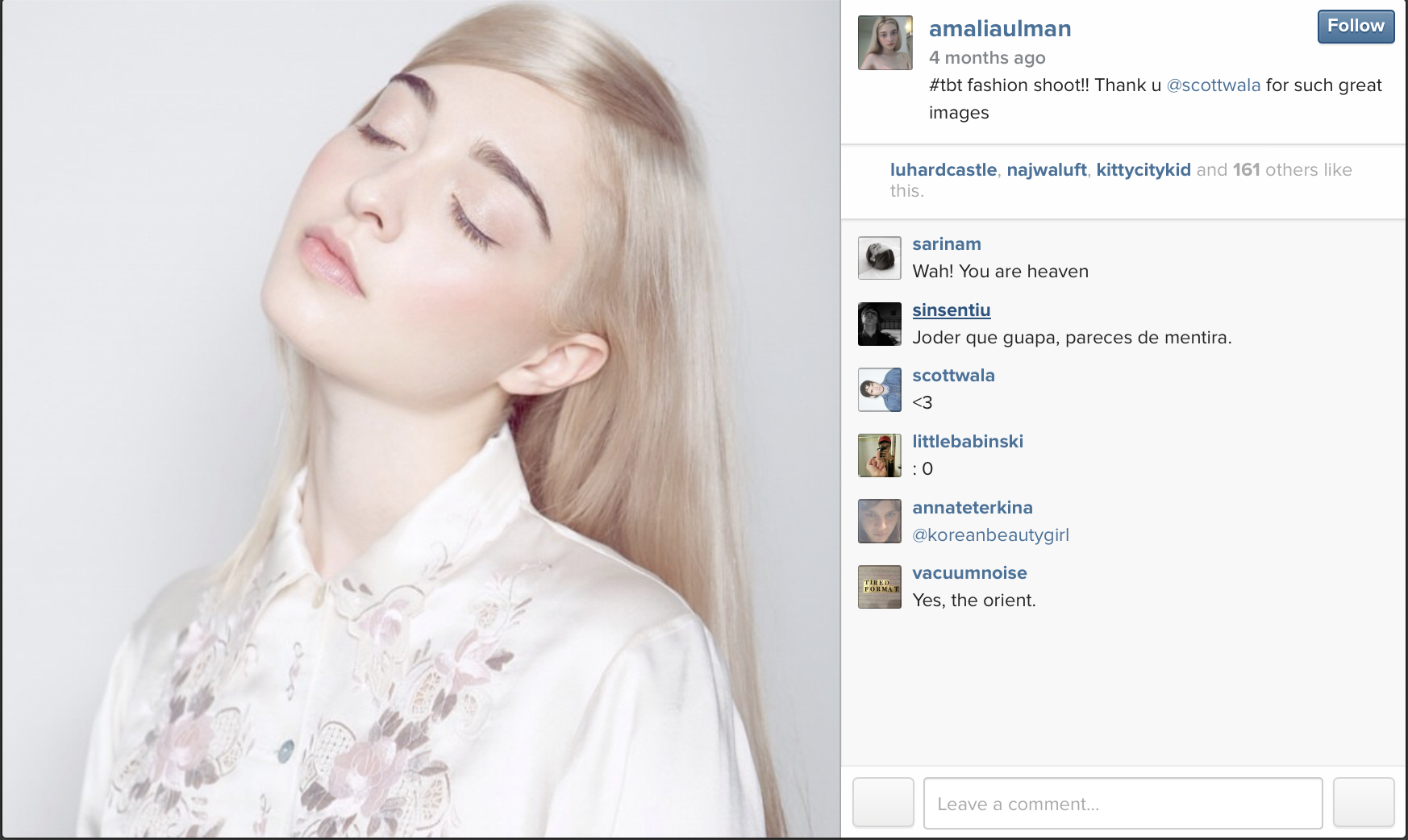

As a protest against this identity factory powered by social media platforms, Amalia Ulman came up with the idea of a fictitious Instagram performance that eventually became such a big hit that it was exhibited in major institutions like Tate Modern, and the whole performance is now archived on Rhizome. To summarize shortly, the performance evoked the narrative of a well-known playbook: 'The crash and burn tale of a beautiful girl'.3Emma Maguire: Girls, Autobiography, Media: Gender and Self-Mediation in Digital Economies, Palgrave Macmillan, 2018. 181. Ulman’s inspiration were teenage girls turned movie and pop stars like Amanda Bynes and Britney Spears whose personal lives were constant targets of tabloids and paparazzi back in the day, and whose lives spiraled out of control while millions of people were watching: their mental breakdowns were scrutinously followed, broadcasted and commented by the media and the audience alike.

Ulman’s 5 months long Instagram performance followed the same pattern, and her transformation went through three stages with three different identities: first, she took up the role of a small town girl moving to a big city, but the girly Instagram persona soon took a darker turn. The bubble gum pink feed full of toys, Starbucks coffees and cutesy selfies were replaced by photos of her fitness journey, expensive clothes, accessories and plastic surgeries, funded by her new-found profession as a sugar baby. This stage inevitably headed towards a publicly broadcasted mental collapse, and upon her return, Ulman took up the role of a health conscious wellness freak, posting about her schedules of doing yoga, drinking her cleansing juices and finding her way back to a socially acceptable lifestyle. A fundamental part of the project was that apart from her family, Ulman kept the truth behind her transformation in secret, so all her colleagues, friends and followers of her artistic journey were stunned by her unexpected metamorphosis, while her freshly gained followers most probably had no idea about the artistic side of Amalia Ulman.

Excellences and Perfections had numerous aspects that would be worthy of interpretation but in this essay, I’d like to focus on two phenomenon that will also help me clarify the upsetting nature of the current state of online representation.

Who Has the Camera, Holds the Agency

Even though Ulman’s project was scripted well ahead, she was also open for organic developments that are inevitably part of any performance that takes place on interactive platforms. This was no different in the case of Excellences and Perfections, either: once she started posting photos of herself that complied with the preferred aesthetic of the internet as we knew it in 2014, the likes instantly went up, and soon the offers arrived, as well. Men who started following her kept sliding into her DMs, offering to take photographs of Ulman. When the professional photographer of the brands Urban Outfitters and American Apparel approached her, she eventually said yes, and later she commented: 'I accepted and I modeled for an unpaid photoshoot 'cause girls want to get their portrait taken for free, of course.'4Do You Follow? Art In Circulation 3. London, October 17, 2014. Featuring Hannah Black, Derica Shields, Amalia Ulman. Transcript: https://rhizome.org/editorial/2014/oct/28/transcript-do-you-follow-panel-three. She also pointed out that the huge number of offers initially surprised her but when she gave it some thought, she concluded that there is nothing truly shocking about them. Because picking up the camera and taking photos of her also meant that the photographer takes domination over their subject: by making decisions about her representation, they can also take away her agency; they would one the ones defining who Amalia Ulman is and what it is she lets her follower base see about her.

In their book Narcissus in Bloom: An Alternative History of the Selfie (2023), Matt Colquhoun analyzes the common cultural trope stating that we live in a more and more narcissistic society and one of its manifestations is the epidemic of taking and sharing selfies.5Matt Colquhoun, Narcissus in Bloom: An Alternative History of the Selfie, London: Repeater Books, 2023. The book disagrees with this statement, and by taking a historical look at the self-portrait (starting from Dürer and Caravaggio), it guides us to our present day, detailing the psychology and sociology of selfies. One of Colquhoun’s most interesting remarks concerns the self-transformative power of selfie-taking: they cite an infamous tweet of Paris Hilton where the celebrity stated that a photograph she and Britney Spears took in 2006, turning the camera towards themselves instead of exterior subjects can be considered the invention of the selfie. Even though its accuracy can be challenged, Colquhoun claims the notorious photo is indeed the start of something new: a new era of celebrity.

Although, at first glance, we may think there is nothing innately interesting about a picture of two of the most photographed women of the 2000s, it is precisely because they were so frequently and intrusively photographed by others that their selfie inaugurated a more autonomous gaze, providing a privately constructed window into the lives of two otherwise very public figures, seemingly for the first time.6Colquhoun, 17.

What Colquhoun draws attention to is even though these women were constantly followed and photographed by paparazzi and fans alike, the act of taking the camera in their own hands and showing themselves in a light they felt fitting is a revolutionary reaction to their media representation mostly defined by judging and humiliation. This interpretation also sheds some light on why the men who kept offering Ulman their services in taking photographs of her weren’t just offering her favors: they wanted a dominant hand in defining her narrative.

Comply or Be Canceled

When talking about her work, some of the most definitive questions Ulman asked herself were the following: 'How is a female artist supposed to look like? How is she supposed to behave?'7Do You Follow? Art In Circulation 3. London, October 17, 2014. Featuring Hannah Black, Derica Shields, Amalia Ulman. Transcript: https://rhizome.org/editorial/2014/oct/28/transcript-do-you-follow-panel-three. The answer lies in the comment section of her performance: not like this.

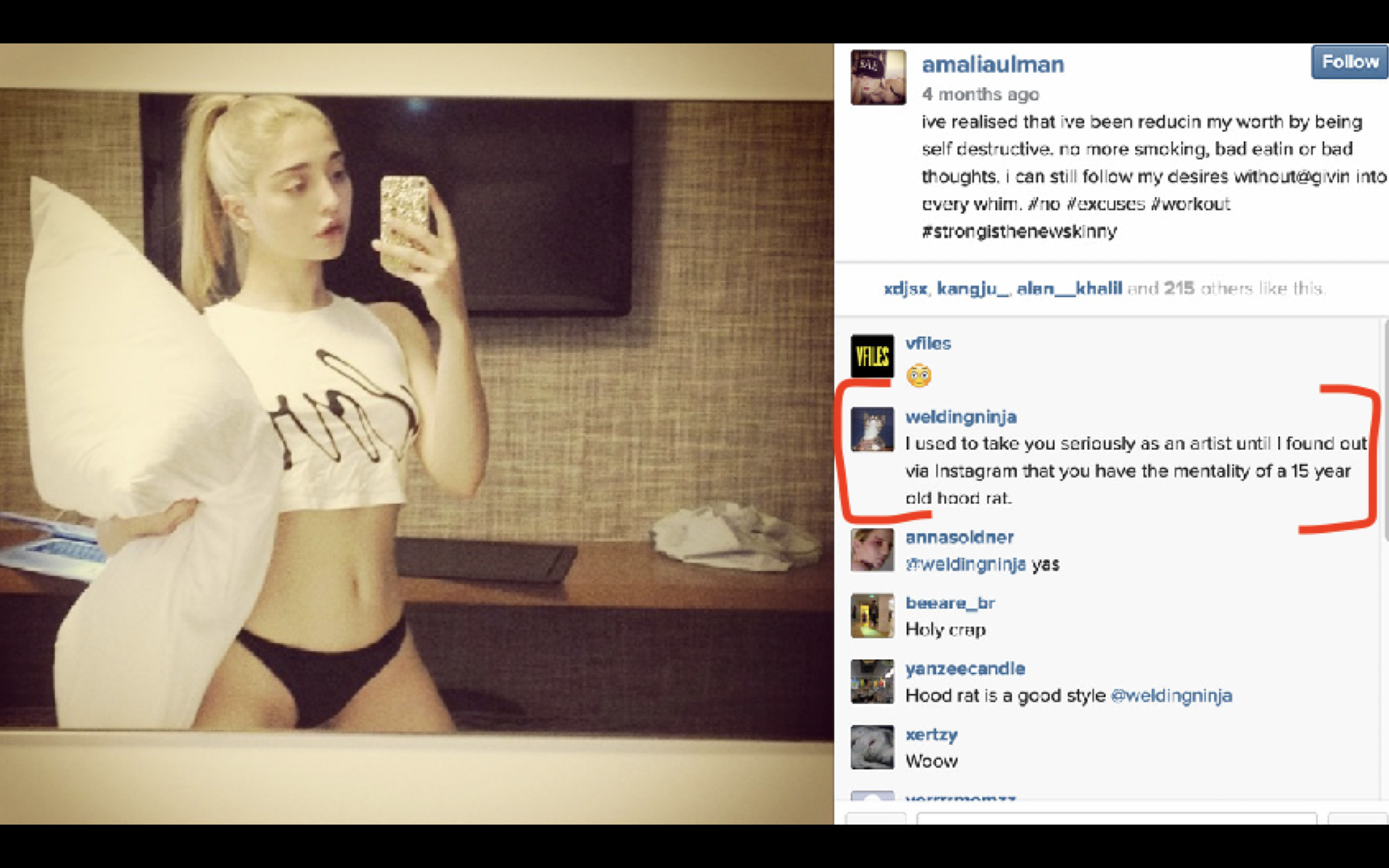

An intensely powerful element of Ulman’s social media performance is that the audience’s vitriolic, threatening and abusive comments under her posts were also considered an integral part of the project – just like in the case of any social media profile where the comment section provides a chance for the viewers to interact, ask their questions, share their thoughts and exchange ideas with other commenters. Or – more frequently than not – to vent, criticize and judge. In the case of Ulman, these commenters either complimented her transformed appearance, or became harsh critics of her metamorphosis, and deemed her unworthy of her artistic legacy, for example: 'I used to take you seriously as an artist until I found out via Instagram that you have the mentality of a 15 year old hood rat.'

The fact that these comments were also archived, moreover, even printed in the catalogue of the performance showcases Ulman’s greatness: it helped the work to become more than a mocking role-playing game; it is also about the unchained reality of how we interact with each other online.

In her essay discussing Ulman’s performance, Emma Maguire captured the double sided nature of the expectations women constantly face online: the very aesthetic and behavior that attracts followers and their likes (featuring well-dressed women in good physical shape with flawless makeup who regularly post selfies of themselves and photos of their lifestyle) are also a common target of criticism, oftentimes in the comment sections.8Emma Maguire: 'Hoaxing Instagram: Amalia Ulman Exposes the Tropes of #Instagirlhood' in: Girls, Autobiography, Media: Gender and Self-Mediation in Digital Economies, Palgrave Macmillan, 2018. 175-204. The critics mostly argue that these women are superficial and narcissistic, and their oversharing behavior is reprehensible because they are sexualizing themselves for attention. To put it bluntly: the exact behaviors and aesthetics that pave the road to success on Instagram also turn out to be triggers for a myriad of criticism and harsh judgement.

When reflecting on her performance, Ulman said: 'Excellences & Perfections is a project about our flesh as object. Your body as an investment. How do we market this flesh? How do we price this meat? And how long will it stay fresh for?'9Do You Follow? Art In Circulation 3. London, October 17, 2014. Featuring Hannah Black, Derica Shields, Amalia Ulman. Transcript: https://rhizome.org/editorial/2014/oct/28/transcript-do-you-follow-panel-three. This aspect of her project hasn’t lost a dime from its relevance throughout the decade that has passed since its publication. Even though, in theory, we are much more literate in the workings of social media platforms than ten years ago, practically nothing has changed when it comes to interpreting and evaluating the fictitious character of social media content.

The Cruel Optimism of Leading Our Lives Online

As Ulman’s performance vividly showcased, the inherent logic of personal branding and social media presence is permeated by the necessity of negative experiences. This mechanism is similar to what Lauren Berlant described in her book Cruel Optimism (2011). Berlant writes in the introduction:

A relation of cruel optimism exists when something you desire is actually an obstacle to your flourishing. It might involve food, or a kind of love; it might be a fantasy of the good life, or a political project. It might rest on something simpler, too, like a new habit that promises to induce in you an improved way of being. These kinds of optimistic relation are not inherently cruel. They become cruel only when the object that draws your attachment actively impedes the aim that brought you to it initially.10Lauren Berlant, 'Introduction' in Cruel Optimism, Duke University Press, Durham and London, 2011, 1.

Her theoretical framework is mostly cited in the context of politics and social mobility, especially in relation to the American Dream. Cruel Optimism seriously questions the long-lasting fantasies of this concept, namely that social upward mobility and a constantly evolving life is possible for anyone, given they are blessed with willpower and perseverance – a thought many cannot identify with anymore, eg. members of the Millennial generation who are constantly accused of reckless financial decisions, and their inability to become homeowners is often falsely and mockingly led back to their overconsumption of avocado toast and coffeeshop lattes, and not the crippling housing crisis. So even though this generation was raised with the promise that hard work pays off, and following their passions and pursuing their dream jobs will lead to success in the end, they mostly hit walls realizing these dreams while blaming themselves for not being resilient enough to make it.

But I believe that her notion can be extended to the workings of social media, as well, which can be considered a tool not only to document but also to manifest a good life. As a modern version of fake it till you make it. But what exactly is a good life? All social media profiles give a personal answer to this question: what is mediated on each and every account is that particular person’s vision of how their kind of good life looks like. It’s not necessarily the one they actually live – but it’s definitely how they want their life to be represented. Apart from manifestation, with each public expression and revelation of ourselves, we seek affirmation and validation. But what we get in return might paint a gloomier image – and this is how cruelty comes into play. Because however carefully we try to protect our public image (on social media and beyond), we are less and less capable of overseeing what others intend to do with our images… and the scale of this uncertainty can range from slightly embarrassing to threatening and illegal, even.

Whose Representation and Whose Agency?

While commenting on her project, Amalia Ulman oftentimes recalls a certain behavior of her male followers, namely that they wanted to take the camera out of her hands to take photos of her, even though it was obvious she was good at taking her own. She eventually agreed to take part in a studio photo session, as a consensual exchange: she accepted being photographed and used the images as she intended to use them. But what happens when no consent is given? What happens when the Instagram photographs are taken out of context and end up on unintended sites? Or event worse: what happens when we are not even aware of our photo being taken publicly and being uploaded to sites whose existence we don’t even know of?

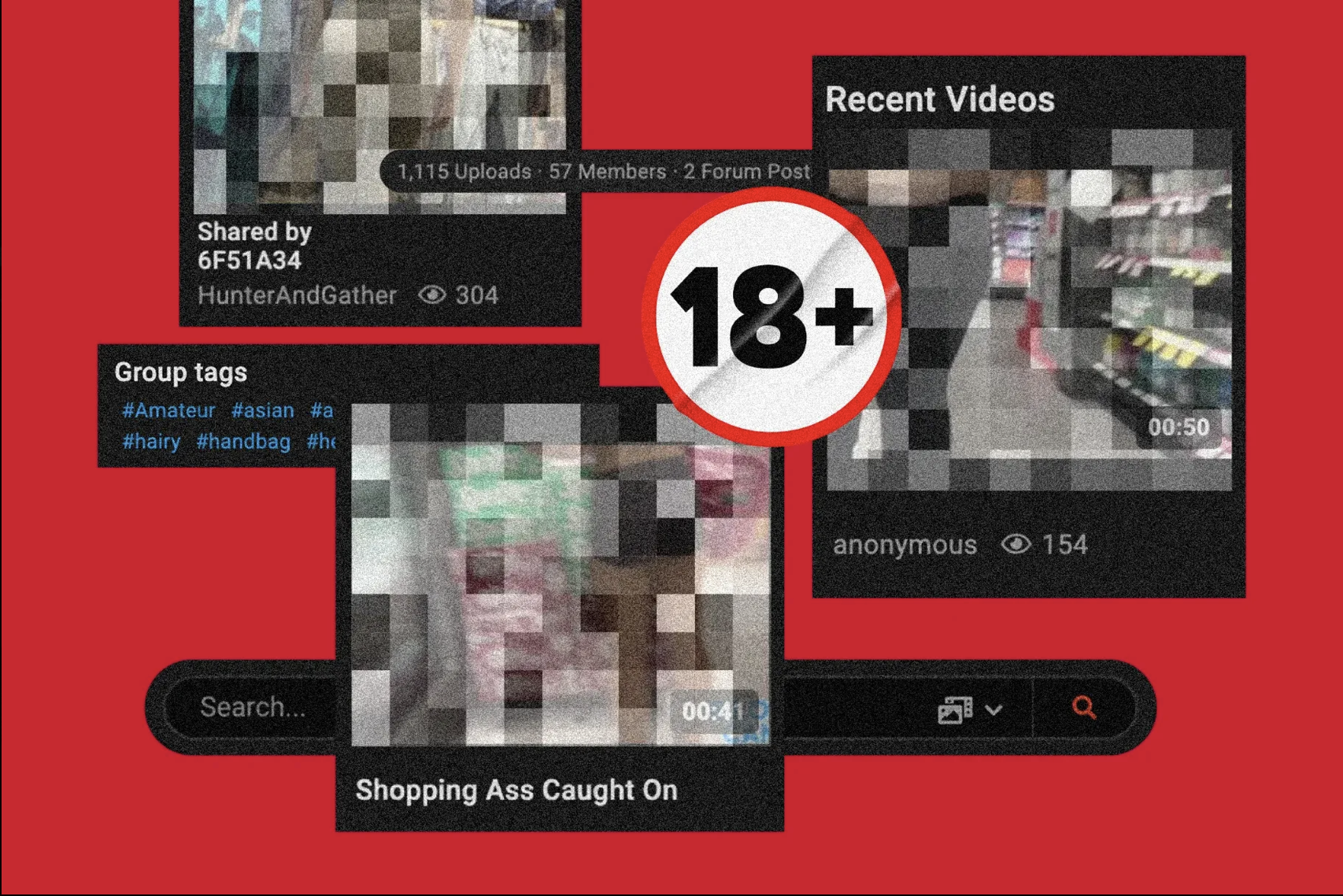

This was one of the central themes of the Motherless scandal that shattered the Hungarian online public last summer. To shortly summarize it: a Reddit thread shed some light on a porn site called Motherless (that – according to its description – is a moral free webpage), and revealed that it contains a group titled HUNT HER DOWN, full of photos of Hungarian women, also listing their names, ages and the city they live in. The photographs were either stolen from their Instagram or Tinder pages, or worse: they were taken on the streets, on the metro, or other public areas where they had no idea they were photographed. Some of them were even taken in public toilets, or were shot from outside of hotel room windows. Besides the women, a number and a currency appears on these images: the price these men would have been willing to pay if they were actually hunted down. Under the photos, the commenters shared their most perverted thoughts on what they would do with the person if they could get their hands on them. One of the reasons this issue became a big scandal is because a famous Hungarian influencer was also among the victims: a photograph of her in a swimsuit was saved from her Instagram account and uploaded to Motherless with a price tag.

The timeline from here sheds some light on why it was one of the most anxiety inducing misogynistic scandal of the Hungarian digital sphere:

- When the site was contacted to remove the content, the owners threw up their hands, stating they take no responsibility for the content appearing on their site, it’s the responsibility of the user who uploads the images.

- While the influencer appearing on the photos tried to get the information out there, in order for women to find out whether they were affected and what their options are if they were, Instagram restricted her account, stating content like this goes against its terms and conditions.

- One of the victims who actually turned to the police got gaslit by the officer interviewing her, stating that the commenters are only 12 year old boys, then asked the girl if she is bothered by this case because she was shy, then told her she should be glad for getting compliments.

- Even in the case of those women who made a complaint by the authorities, an investigation could only be opened for abuse of personal rights and privacy (even though the threats and possible dangers move beyond the matter of stolen images.)

This very specific incident can provide more general takeaways, or more precisely, questions that no judicial system has straightforward answers to: whose responsibility is it to decide whether the threats coming from a page like this are real? How can we tell when online threats are turning into real life dangers? How can it be assessed when escalation might be expected? As an outcome of the Motherless scandal, many women in Hungary report feeling anxious because they feel helpless, since there is no legal framework for their problem to be correctly handled. And as another outcome, many women (who were not affected in this round, or at least they don’t know if they were) worry because they feel there’s nowhere to hide - their photographs can be taken anywhere, anytime, without them realizing it.

This is the point where we return to Ulman’s performance and its reception: what men taking photos/videos in the streets do is to take away the agencies of these women, and make the decision instead of them where and how they want their images to appear. The unpredictable nature of this practice can induce anxieties, as the people appearing on the footage have absolutely no control over what happens with their images – and also cannot influence what the viewers are inspired by looking at them.

Swifties for Trump, Swift for Kamala?

As the US election campaign was heating up last summer and autumn, half the world was waiting for a very specific endorsement: the one of Taylor Swift’s. But while the pop star was contemplating her choice, others took matters in their own hands.

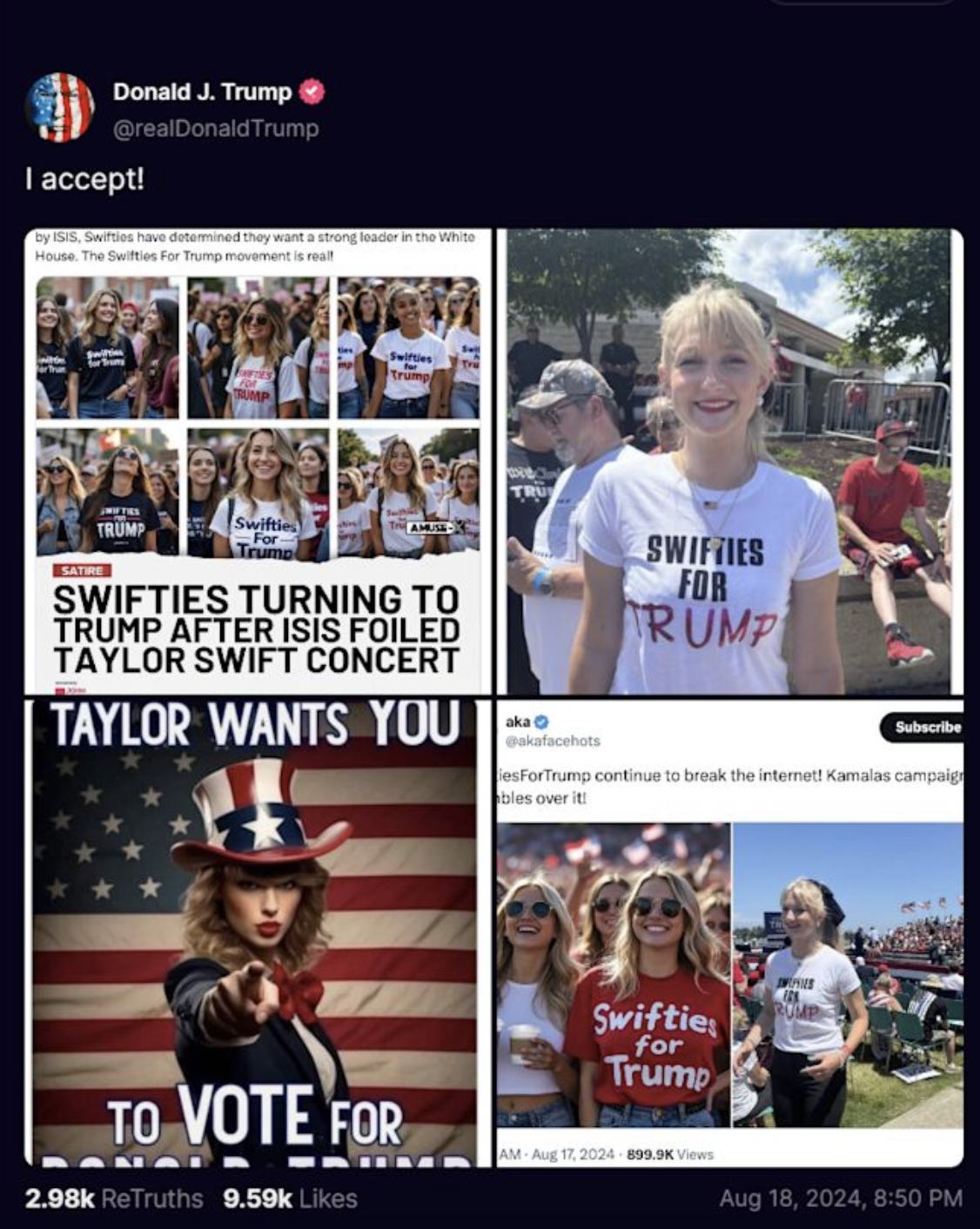

Last August, Donald Trump, regardless of the fact that Swift hasn’t endorsed anyone publicly yet, shared a post on Truth Social, and kindly accepted the support of Swifties and Taylor Swift herself. The post consisted of 4 photos: only one of them showed a real-life person (Jenna Piwowarczyk, who wore a homemade T-shirt to a Trump rally in Racine, Wisconsin, Trump rally, emblazoned with the words 'Swifties for Trump'. Piwowarczyk is now selling her homemade T-shirts on Etsy.) The other photos of Swifties and Taylor Swift herself were all clearly AI generated, moreover, the former ones were labelled even as satire. That didn’t stop Donald Trump from campaigning with them.

Meanwhile, a couple of weeks later, following the presidential debate, Taylor Swift shared this photo as her actual endorsement, showing support for Kamala Harris, and signed it as Childless Cat Lady, as a comeback to JD Vance’s snarky remark about Democrats and women in general who decide or end up not having children.

This case might seem far off from the anxiety-inducing Motherless scandal and no one’s physical safety was in immediate danger, deep down these issues stem from common root, namely that women’s photographs were used in an environment they did not consent to. Even though it is well-known that Swift is a Democrat and endorsed Biden/Harris in 2020 (so she clearly stands on the opposite side), it did not stop Donald Trump or a Swift fan from actually using her name, image and the power of her fanbase for Trump’s benefit. This might not seem a big deal in the normalized post factual media landscape where we don’t even bat an eye if the presidential candidate of the United States campaigns with obvious lies, but it’s still worth taking a step back and pondering over its consequences on representation. We need to ask the question if it is moral for Swifties to unite for Trump while Swift herself openly stands against him? If the image is AI generated, can we simply look at it as fiction? In a situation where the person who is depicted on it clearly stands for the complete opposite? And in this case, who represents whom?

Vanda Sárai is a Budapest-based independent curator, art writer and researcher. She completed her BA and MA studies in Budapest and Jena, and is currently working on her PhD at Eötvös Loránd University, focusing on the effects of attention economy and digital culture on contemporary art and its institutional system. She is a guest lecturer at the Art and Design Department of Metropolitan University Budapest. She was a member of the curatorial collective, Teleport Gallery (2016-2018). As a curator, she won the Esterházy Art Dating Prize and the MODEM Prize for Young Curators. Her most notable shows were: Time of Our Lives (co-curated with Tamás Don and Ferenc Margl), MODEM (2018); #IFeelSeen, MODEM (2021); WHAT THE RUG? Carpets in Hungarian contemporary art, 1111 (2023); I’m Afraid I Can Do That, TORULA (2023); Kádár Emese: NOT_FOUND, The Space Gallery (2024). Between 2017-2021, she worked in the editorial team of the Hungarian art magazine, Műértő. In 2022-2023, she was the gallery manager of the non-profit art space, 1111. She is a member of AICA Hungary.