As a designer, when I choose a topic to discuss, it is usually based on my own experiences. As I am a keen observer of human behavior, I noticed something in my own behavior has changed in the past years. My emotions were being affected by something. Something that was not human. Something that slowly became a part of me without me realizing it. And I was not the only one in my surroundings experiencing this. I’m talking about the smartphone and how we communicate on social media - by sharing our lives.

Every time I went on holiday, hosted a party, spent time at school, worked on a project, visited friends, or attended expositions, my iPhone was with me to share these experiences with all my social media followers on Instagram. I have used this app since I was 16 years old and it has been my public diary for eight years. Now, I use the app every day. I am at a point where I have set an alarm that goes off when I have spent more than 15 minutes on it. The alarm has gone off more often than I want to admit. Sharing has become an integrated part of my daily life, which is undoubtedly troubling. However, stopping is difficult. Most of my friends are in their twenties and are engaged in the creative economy. This means that to promote our work, especially in COVID times, social media platforms are the main tool to get publicity, customers, and jobs. Professional networking is exponentially moving to the online world since the offline one has been out of reach. However, this type of networking hasn't been the only part of our lives that moved to the online world. Social media platforms have become the primary social realm for keeping people in your private life up to date too.

David Brooks, a political and cultural commentator who wrote the book The Second Mountain explains it perfectly:

Social media reality may be seen as a magical realm where we belong. That’s where the tribes gather, and that’s the place to be – on top of the world. Social relations in “real life” have lost their importance.

I think this is the case for many of my friends that are Instagram users, creatives or not. Before seeing each other in real life, we already know how our week looked like because we saw each other the snippets of the week on social media. Curious animals that love to have a sneak peek of someone else’s life. My friends and I grew up during social media’s technological development, so thinking of a life without it seems impossible, but if I think about how many parts of our lives are connected to social media, it worries me. What negative effects does our social behavior online have on our real lives?

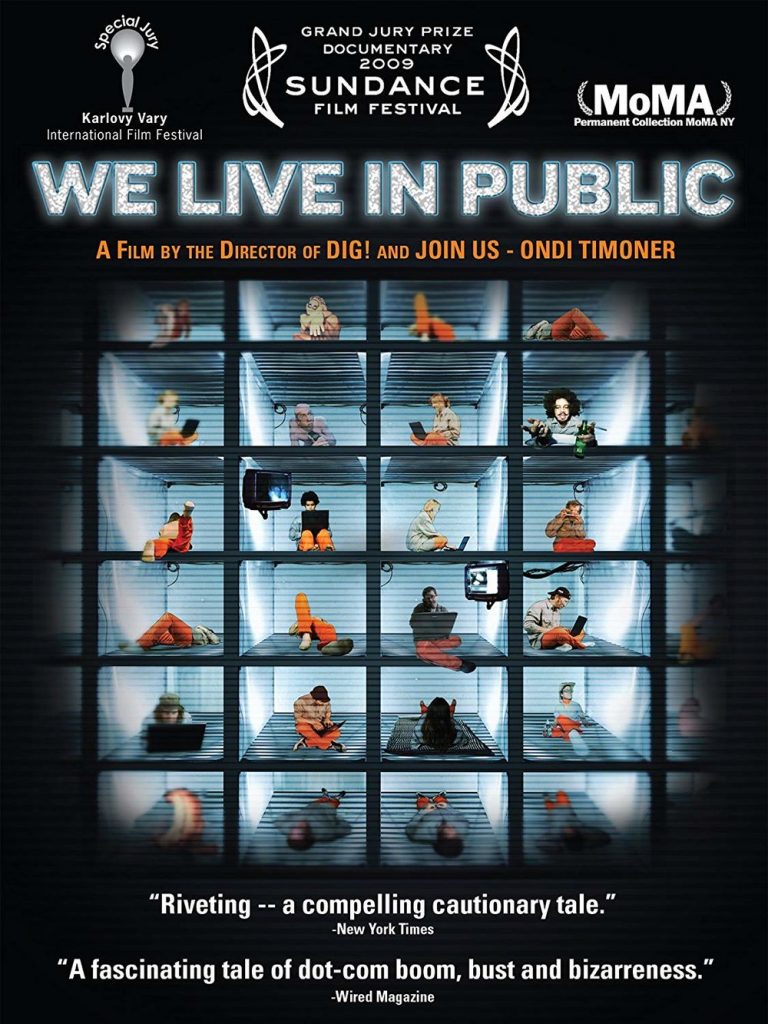

Wondering about this made me think of a documentary called QUIET: We Live in Public by Ondi Timoner from 2009. The film discusses exactly why humans are so prone to using social media in the way we do today. The film follows Josh Harris who is called one of ‘the greatest internet pioneers you’ve never heard of '. He was the inventor of Pseudo.com. After creating this online platform, which was one of the firsts, he conducted various social experiments. One of them entailed putting 100 people in an adapted basement for three months in 1999. During this period, their intimate rituals such as eating, having sex, sleeping, and going to the toilet were live-streamed. With this experiment, he wanted to show that people would willingly let go of their privacy because of the deep desire for connections and recognition, which was further facilitated by the development of technology and media. In an interview, Timoner states that Harris’s project was 'a physical prediction of life online,' anticipating the rise of Big Brother and social networking. I see his work as a metaphor for the Instagram world where people’s lives are shown in frames as well. As the movie poster illustrates, the two aesthetics happen to coincide.

TECHNOLOGICAL SADNESS

'Technological sadness', a term introduced by media theorist Geert Lovink, describes it all. He explains as follows:

Social media are designed for us to continue. We scroll, we like, we wait for responses, we wait for information to come in, for others to come online, to respond again. This leads many of us to a point where we break down. Technological sadness happens when it is all too much. You want to stop, you put the phone away, but that is not possible.

I started to wonder what technological sadness looks like on Instagram and who experiences technological sadness.

The people most affected by Technological Sadness are digital natives, a term created in 2001 by Marc Prensky, a scholar who researches humans adapting to technology. Digital natives are the generations who grew up using computers and the internet– namely the younger millennials and Generation Z.

Why are digital natives so tempted to use social media? Doreen Massey, a social scientist and the author of the book Generation Me, notes how those born in the 80s and 90s tend to focus on self-development over work. She elaborates:

The rise of individualism and neoliberalism is therefore perfectly reflected in the words and phrases we use: in the last decades of the last century, terms such as ‘the individual’ and ‘the malleable human being’ became very popular. Credos such as: ‘your life is your life’, ‘belief in yourself’ and ‘follow your dreams’ were pretty much the soundtrack of the eighties and nineties.

Generation Me build their identities by comparing themselves with others online. It is not strange then, that their emotions are affected because social media has become a part of their lives from the beginning.

STORIES

Instagram Stories, which were launched in 2016, definitely interest me the most. This function lets users posts photos and videos that vanish after 24 hours and is used by 500 million people every day. The effects of this function include users having unrealistic comparisons to others. Lovink describes the function as follows:

Instagram Stories bring back the nostalgia of an unfolding chain of events – and then disappear at the end of the day, like a revenge act, a satire of ancient sentiments gone by. Storage will make the pain permanent. Better forget about it and move on.

There is an increasing pressure to share every day because, after 24 hours, it may look like nothing happens in your life as there is no activity showing. It makes us want to capture daily activities that are not memorable, just because we want to show others we are doing something. Paul Verhaeghe, professor of Psychoanalysis at the University of Gent, says that we are 'living in a performance society where everybody is focused on performing and social media magnify our individualistic competitive society. We can compare ourselves perfectly all day long.' This made me think of how Stories takes advantage of our vulnerabilities and facilitates the confrontation with others whom we start to see as competitors.

FOMO, INFLUENCERS AND HIGHLIGHTS

Since the amount of Stories has been increasing, the chance to get FOMO (fear of missing out) is bigger, which usually happens when users feel they have missed out on certain social opportunities and cannot connect to others that have had that chance to the extent they would like to. Users viewing these activities from others on Instagram can cause them to feel excluded. Scholars Aarif Alutaybi et al. researched what aspects of social media increased FOMO and concluded that more than half of social media users have experienced FOMO. Moreover, it can also lead to a range of negative life experiences such as a disturbing sleep rhythm, reduced life competency, emotional instability, and negative physical well-being.

On a platform such as Instagram users see all the “highlights” of people’s lives, but they rarely get to see the “behind-the-scenes”; the mundane things that everyone goes through. How is posting what we think is Instagram worthy influencing how we define ourselves? This is where influencers come in. In her book Gold Mountains, Doortje Smithuijsen explains how influencers' lives revolve around the platform. She mentions that 'for those who look no further than what they get portrayed on their phone screen, the purpose of life is reduced to a flat, square ideal image, a beauty ideal that it yields.' These are people who have made it their job to share their life online. They are the inventors of ‘the highlight reel’ a term that explains our obsession with only showing our highlights online. The ‘spontaneous’ pictures we see from influencers could have taken hours to create, which is something that is often not taken into account when consuming this type of content.

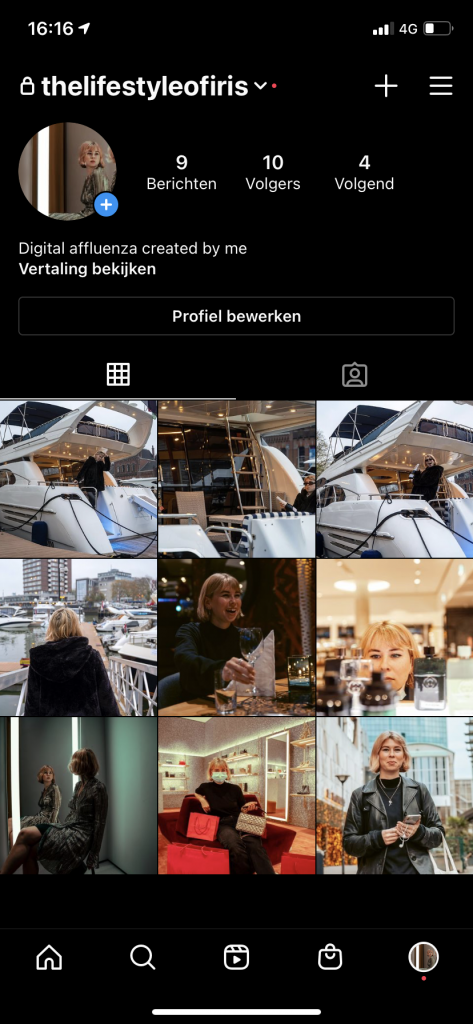

Experiment 1. In the image above you see me replicating the life of an influencer, to create a better understanding. I broke into a luxury port Rotterdam and climbed onto a yacht, only to realize that there were people inside. When I told them it was for a school project they laughed and offered me a bottle of champagne for the photo. Afer that I went to an expensive hotel to ask if I could enter one of their most luxurious rooms to take pictures in. They said no. I could, however, take a photo in their restaurant. Then I went to the Bijenkorf, a luxury department store in the Netherlands, to do some shopping. I put on expensive perfume and a dress that costs 1100 euros. I did all of this while my friend who is a photographer followed me. Walking around with a photographer made me uncomfortable, but it also make me realize that if you want you can be an influencer, you can create whatever high light reel you want. It doesn’t even have to be real.… )

#ISHARETHEREFOREIAM

In the TedTalk Connected, but alone? Sherry Turkle explains how 'Technology appeals to us most where we are most vulnerable.' Vulnerability took root when we started separating ourselves from each other and started connecting with our phones. Our phone became one of our most personal tools when we started to carry it with us everywhere. In the TedTalk, Turkle explains 'how the phone offers us three gratifying fantasies. One, that we can put our attention wherever we want it to be. Two that we will always be heard. Three, that we will never have to be alone.' The problem becomes that we no longer want to be alone. Because of the increased amount of contact, we started to lose real conversation and connection. We can now edit anything before sharing. In exchange, there is no authenticity or spontaneity.

Turkle also wrote a book called Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other in which she introduces the following statement: “I share, therefore I am.”

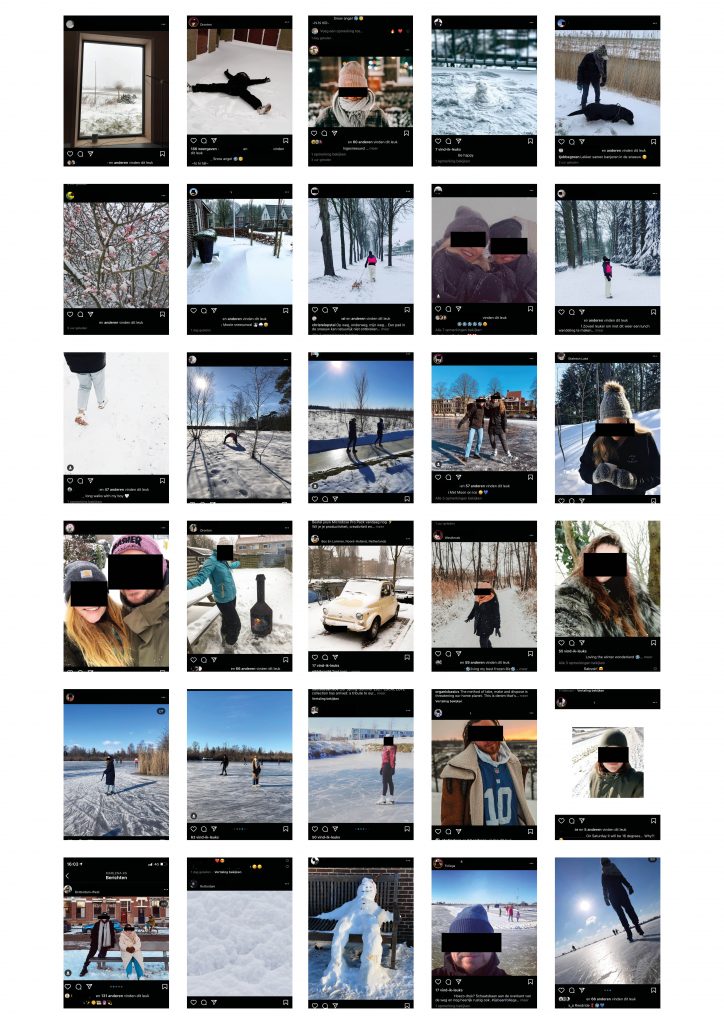

An example of #IsharethereforIam happened when an extraordinary phenomenon occurred in the Netherlands last winter. It was snowing! Everyone went outside to enjoy this beautiful weather and we all started sharing. Why wasn’t being in the snow enough? Do users have to have proof that they were enjoying the snow?

OVERCONSUMPTION OF SOCIAL PHOTOS

The way we are capturing moments is changing - instead of a photo just being a photo it has become a social photo. Nathan Jurgensen notes the following in his book The Social Photo:

To the degree it's ephemeral, the social photo does the opposite: it interrupts the traditional photographic mode of fixing the present as impending history, positing instead a captured moment that is indifferent to such recording.

Social media changed the way we see photography. When they take a snapshot, an active social media user already thinks about how it will look in the online world, always taking a few of them, making sure they have the best angle, lighting, etc. In the article A life more Photographic; Mapping the Networked Image Katrina Sluis and Daniel Rubinstein describe it as the following:

Since the beginning of the twentieth century, the snapshot has been the archetypal readymade image: placeholder for memories, trophy of sightseeing, produced in their millions by ordinary people to document the rituals of everyday life.

On Instagram, more than 300 million photos get uploaded per day. Every minute there are 510,000 comments posted and 293,000 statuses updated. We are trying to capture the outside world and hold on to moments by creating them but aren't we losing these moments by our obsession to share them? The problem is that today, making a photo has less meaning because it can just as easily be deleted or taken again. Whenever something feels imperfect, uninteresting, or just meaningless it is in danger of being deleted immediately or never looked at again.

It is not the photo itself we find important, rather it is what the photo says we value. A photo behind your desk to show that you working, a few holiday photos to show your traveling, a photo of your dinner in a restaurant to show off your taste, a photo of your friends to show you are social, a photo with your loved one to show you’re not alone, a photo of your outfit to show you have style, a photo of you going to the gym to show you’re healthy, and a selfie to self advertise. We are not living in the moment itself anymore. We don't even see a photo as a memory we want to keep.

THE PHOTO IMPAIRMENT EFFECT

When I came across 'Instagram and Snapchat Are Ruining Our Memories' an article written by Eda Yu, I found out about ‘the photo impairment effect’; the more photos and videos we take with our smartphones the less we remember. This causes our phone to become our external memory, as if we are offloading our own memories onto the device.

Julia Soares and Benjamin Storm study the influence of digital technology and wrote about 'the photo impairment effect'. They suggest that, when taking photos on phone cameras, people disengage from the moment to capture the experience and therefore remember less. It shows how we are expecting the smartphone to remember for us, becoming our external memory storage. But what if this external memory is ruining our capability, or capacity, of remembering moments. In their groundbreaking paper, Forget in a Flash: A Further Investigation of the Photo-Taking Impairment Effect, Soares and Storm conducted an investigation of Snapchat, a platform where photos disappear after 24 hours, which was also the inspiration for Instagram Stories.

When I interviewed Soares she mentioned that:

Everybody is walking around with a phone these days. One of the consequences of this is that you're constantly making decisions about what's worth recording, what's not worth recording, what's worth looking up, what's worth uploading for other people to see or not. All these decisions and having this unlimited potential in your pocket at all times, how do they affect our cognition, especially when it comes to these regular interactions - with retrieving stuff that you wouldn't retrieve otherwise, through looking at your phone or getting reminders through social media and also how that makes you think about your memory and in terms of your own life.

To me, this was exactly what motivated me to start my research as well. That social media is affecting our memory was new to me, so I wanted to let my fellow social media addicts know about the dangers of over-capturing. Soares explains that when you take a picture, you start to rely on the object; the phone is there to remember for you. Then there are also the attention disengagements that are pulling us out of the moment:

Generally, people use cameras to direct their attention and move their attention around. Putting a camera between yourself and what you're experiencing causes attentional disengagement. What also draws us out of the moment is the thought of us creating a memory for others. We are not fully experiencing the experience which makes it automatically become less memorable.

Soares and I started talking about how certain moments get lost when we start using our phones to capture them. For me, it feels like we can’t accept that time goes by. Julia mentioned that capturing a moment is never the same as the real thing.

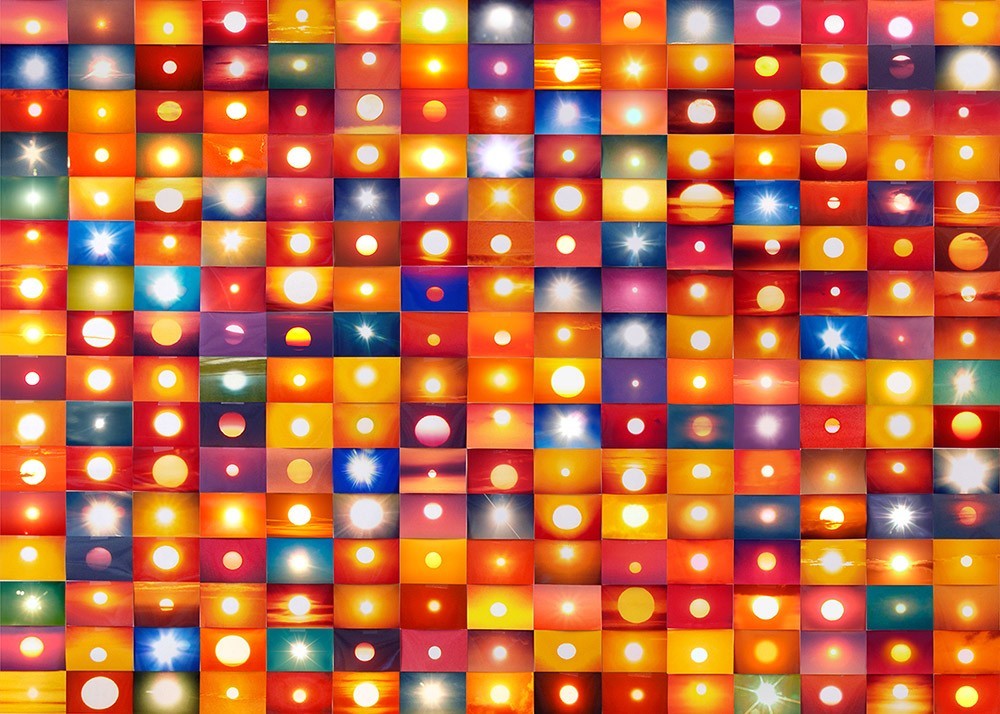

It’s like looking at sunset like you might try to take a photo of a sunset. I don't have a nice camera. Yeah, I just had my phone. So if I try to take a photo of it, it never looks the same. It never looks right. So I always think of it as one of these things that I need to just look at and enjoy because I can't take a photo of it to capture even what I'm seeing. I've been thinking about that a lot, what a camera can't capture.

Soares reminded me of an artist who makes work exactly about this phenomenon. Penelope Ombrico collected all photos of the sun that have been taken and posted on Flickr.

Soares and I started talking about how we can think of methods to stimulate less overconsumption. It wouldn't be possible to not take photos at all because it's in our human nature now, but it is about a balance, according to her. Different photographic technologies affect memory-making in different ways. Analog photography works in such a way that time is needed for the photo. Also, the image cannot be immediately viewed which makes the photo unedited. As a consequence, analog photography will not harm your memory in the way smartphone photography does. Digital photography with a camera is also a bit different. We still pick our moment with a camera. The force of habit with the smartphone is where the problem lies. Soares talked about how interesting it would be if people could only take one picture a day.

OVEREXPOSED

During my studies in industrial design at the Royal Academy of the Art of The Hague this became my research subject. I wanted people to rethink the way we are using our smartphones and how we are using them to share our lives daily online. I wanted to put our behavior under the loop. During my research, however, I found out that active Instagram users already know that what they are doing might have negative effects, deep down.

Everyone recognizes those nights where we keep scrolling through our feed, removed from the real world and absorbed into the digital one. The connections that are moving online can make it harder to get a deep connection in the real world. We have all felt technological sadness. But what was interesting to me was that the act of posting, photographing, and sharing is harmful to the way we remember. The one thing that we assume is a positive feature of social media; capturing moments, having a diary and documenting our life. That one thing is also hurting us. I wanted to confront people with their behavior. Not to say now we can never share content again. But to do it less. Let's not catch every moment. Let it slip away if we feel like it, because we want to be here, now.

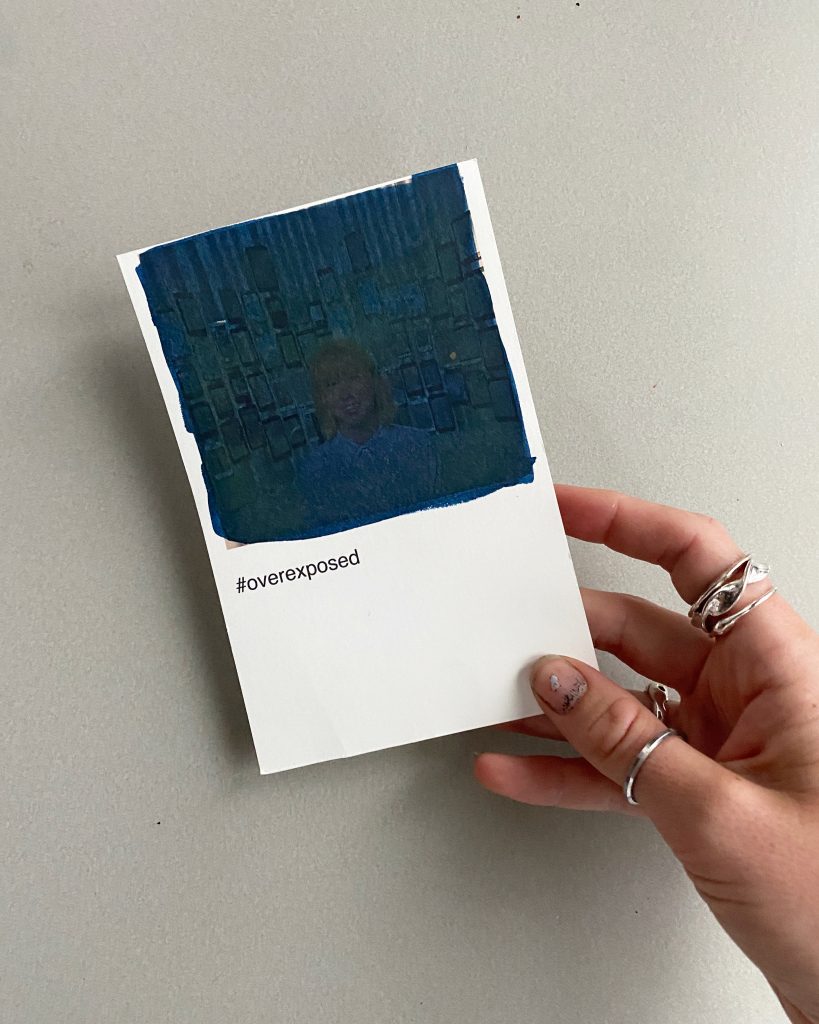

As a designer and artist, I decided to visualize memory loss through smartphone photography through an interactive art installation. I started to visualize the story of the 'photo impairment effect' by creating a unique photo booth; a beautiful metaphor, if you ask me. You go into a photo booth to create ever-lasting memories and you leave with a tactile souvenir.

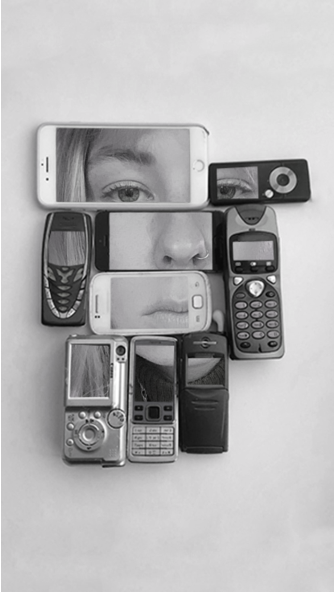

The design of the photo booth has details in it that refer to the online world. The curtains have an abstract-looking print on them, which is based ona picture of my broken iPhone screen - a metaphor for broken memories. The title on the top is illustrated on two hands that are taking a smartphone picture. I chose the title #overexposed because I wanted to refer to humans that are overexposing themselves with their social media usage. But it also refers to the photo that the visitors get in the booth. When visitors enter the photo booth on the inside there is a wall full of smartphones, where their screens have been replaced by mirrors, to raise a feeling of confrontation with the self and the smartphone. The light in the photo booth comes from a single ring light, a tool used by every influencer in town.

When visitors enter a google voice starts speaking:

In the booth, I am the one who takes the photo, but I am invisible for the visitors.

For them, a random human hand comes out, holding a smartphone that takes a photo. They get the printed photo as a memory.

But what they don’t realize is that when they get home the photo will slowly disappear because the images are made with a technique called Cyanotype.

The photo after the Cyanotype reaction.

IS THERE A WAY OUT?

To conclude, I think the digital world has become a permanently disturbed reflection of the real one. The amount of photos we take daily is increasing every day and so is the time we spent on the platforms to watch these photos. Smartphone cameras are being designed in a way that in the future they might see more than our own eyes. There are smartphones with 3 lenses. More than humans have eyes…

Will our behavior change even when realizing we are too obsessed with capturing everything around us though? Will my behavior change? Is there a way out? I have to admit the online world lures me back in every time. Contributing to it. Like everyone around me. I ask myself why is it so hard to stop? Do I even really want to stop?

Reference List

David Brooks, The Second Mountain: The Quest for a Moral Life, New York: Penguin Books, 2020.

Doortje Smithuijzen, Gouden Bergen: Portret van de Digitale Generatie, Amsterdam: De Bezige Bij, 2021.

Geert Lovink, Sad by Design, London: Pluto Press, 2019.\

Jean Twente, Generation Me, New York: Atria Books, 2006.

Nathan Jurgenson, The Social Photo: On Photography and Social Media, New York: Verso Books, 2019.

Paul Verhaeghe, What about Me?: The Struggle for Identity in a Market-based Society, Carlton North: Scribe Publications, 2014.

Sherry Turkle, Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other, New York: Basic Books, 2011.

.

.