"During long periods of history, the mode of human sense perception changes with humanity’s entire mode of existence. The manner in which human sense perception is organized, the medium in which it is accomplished, is determined not only by nature but by historical circumstances as well."

So writes Walter Benjamin, in his famous essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Human sensory perception is a historical fact, through the medium in which it takes place. Beyond social media and smartphones, beyond the obvious, can the drone be the new-old medium of the 21st century? How is sensory perception organized and changed through the (commercial) drone? The drone as hyper-sensory simulacra, the drone as an object of our times, an object of spatial violence and control.

My drone journey began in my beloved city of Palermo, in Sicily, where Manifesta, the contemporary art exhibition, was held in the summer of 2018. Among the various, interesting works, the video work Signal Flow (2018) by Laura Poitras particularly struck me. The theme was the ‘strong presence of U.S. military bases [in Sicily], a pivotal location for U.S. military communications and international military drone operations’. Sicily is my adopted homeland, and although the presence of military bases is a well-known fact, seeing the island from the perspective of communication infrastructure was certainly a new thing for me. The military drones fly over the island – the island as a military platform from where the drones can fly.

What are these deadly weapons? Are drones used as infrastructural tools of communication? How many types of drones are there? What is the difference between military drones and commercial drones? Are commercial drones really harmless objects? Are they innocent toys? Fancy new media?

In Why Media Matters, Nick Couldry writes that “in the contemporary era, it makes sense to think about media not just as a single medium (…), but as linked infrastructures that make possible a certain way of living”. Media are infrastructures of connections, “able to transmit or preserve meanings across space and time”. Let’s think of the drone here, specifically the commercial one, as a medium that is part of this infrastructure of connections. A medium that not only conveys the meaning of our historical time but, in doing so, modifies and organizes human perception.

Enlarge

Terror, swarms and shows

To consider the drone as media, one must first understand what a drone is.

‘Drone’ is indeed a somewhat generic term, encompassing various types of technological objects that can be used in different contexts and for different purposes. We usually refer to Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) or Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV), which are ‘aerial vehicles’ or robots that can perform some kind of task, controlled from a proper distance by an operator on the ground.

In this text, I will explore the commercial drone as a hyper-sensory media. Yet, it would be difficult to argue that commercial drones do not retain, in their essence, some of the destructive characteristics proper to the military ones.

Military drones are infamous war machines, whose purpose is to detect the so-called enemy, to kill, to destroy. They are mainly used in warfare contexts – a death business that knows no crisis. The military drone's real goal is terror. In this sense, they well express the fact that terror, as Achille Mbembe notes in Necropolitics, is linked to modernity.

Some years ago, I had the chilling experience of Killbox, an online game and interactive installation that explores what it means to deal with military drones. The video game consisted of two stations placed at the ends of a table, looking at each other, each one equipped with a screen, headsets, and station control. On one side of the table, the game simulates the point of view of the drone operator who has to make strikes in a war context; on the other side, the player assumes the point of view of the target, the victim. Everything happens in the same virtual environment.

I do not remember exactly how much time I spent on each side of the table, but I remember very well the feelings of anxiety, fear, disgust, and profound sadness. From both the victim’s and the drone operator’s perspective, the physical sensation of the game was quite unsettling - and the rather simple and standardized graphics mitigated only slightly the feeling that, out there, this was a horrendous reality. That’s it: recognizing that that video game was nothing but a simulation of the brutality of life. Killbox brings the manhunt and execution to life on one’s skin, confirming Chamayou writes in his text Theory of the Drone, that ‘aerial warfare is done with terror’.

Drones can also operate in swarms, and this is considered to be the direction in which both the warfare and commercial industries aim. Despite what one might think at first glance, drone swarms are not controlled all at once, but in a separate and coordinated manner. In the military context, the tendency toward separation + coordination is particularly evident. The separation of the individual drones that make up the swarm, is decided not only to facilitate autonomous movements but also derived from the type of drone itself. Within a swarm of military drones, an unarmed drone might map the terrain and give information to an armed drone about where to strike. This type of scenario is very dangerous, not only because of the number of drones involved, but also because of the potentially high degree of automation of each individual drone -resulting in a lack of central control. As journalist David Hambling reports, there is a need for global concern to emerge over these new ‘weapons of mass destruction’.

Enlarge

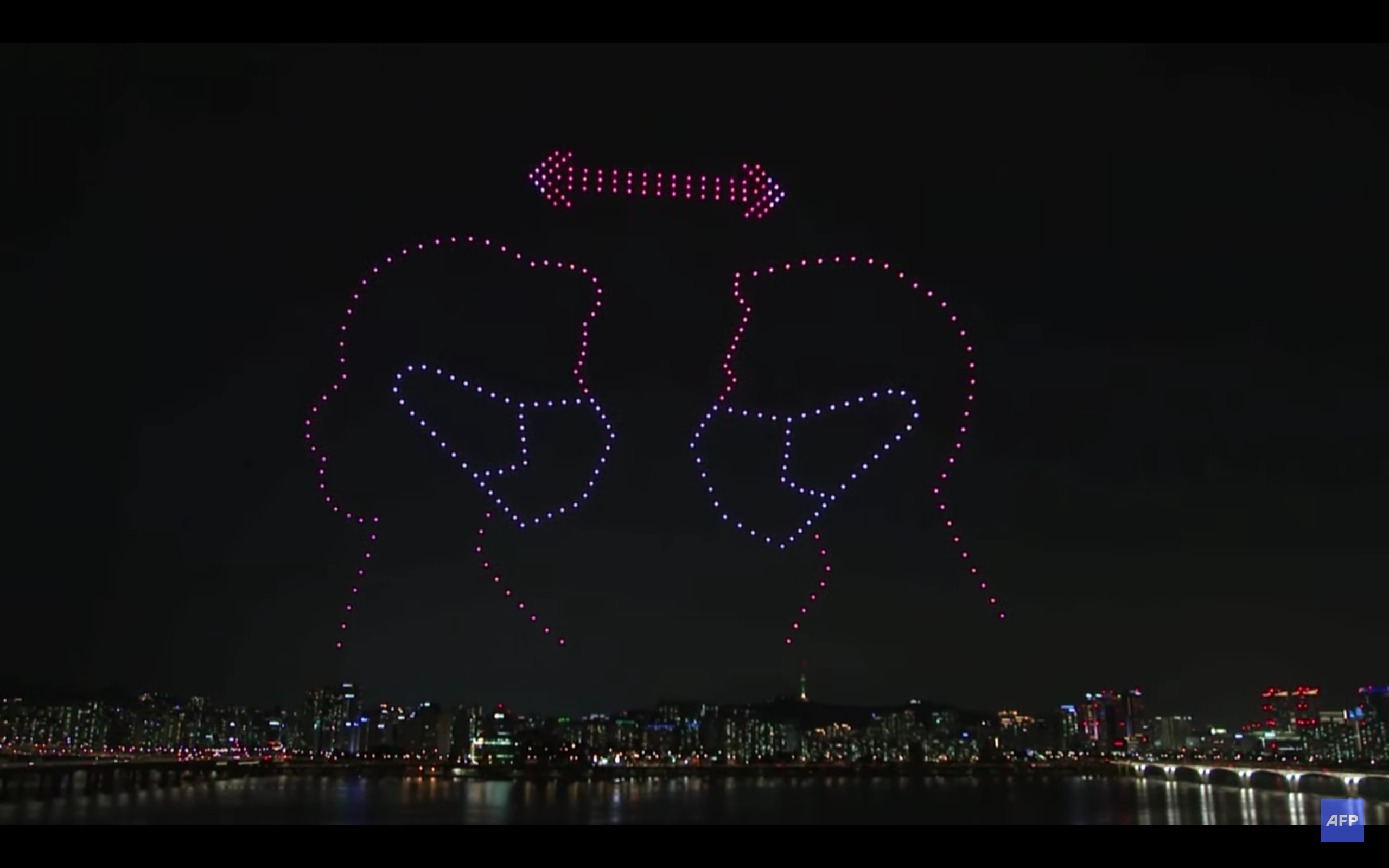

Drone swarms are actually beginning to take hold in commercial and civilian environments as well. This is the case with the spectacular drone lights shows. Here the degree of separation and autonomy is slightly less than in the warfare context since the movements of each individual drone are controlled from the ground by a central computer, which ensures that no collisions occur and that the drones that make up the swarm move in unison with one another. These light shows are certainly striking and capable of truly arousing a sense of wonder in the viewer. Usually, drone light shows are used for big events, for example in the opening ceremony of the 2021 Tokyo Olympics. However, even in the most spectacular of performances, the dystopian coefficient is always around the corner, and it is just a matter of seconds to go from the technologized version of a pyrotechnic show to the real-life transposition of cyberpunk imagery. For example, during the summer of 2020 in Seoul, in the midst of the first wave of Covid-19, the Ministry of Infrastructure and Transportation decided to remind the rules of social distancing and prevention with a drone show (or drone flashmob). Three hundred tiny flying robots soared for ten minutes above the astonished heads of South Korean citizens, creating in the sky graphics of hands about to wash, masked profiles at a safe distance, healthcare workers on the front lines, and finally a nice ‘Thanks to You’, accompanied by a heart. Or at the closing ceremony of the Riyadh Season 2021, cheerful and colorful images of hearts and geolocations alternated with the face of the King and other members of the royal family, faithfully reproduced by the many small flying drones.

The faces of power and the rules of the State are shown through choreographies of cheerful dancing drones, rising above the heads of its citizens - from the sky. Can an image be more symbolic – didactic, even? Dematerialized power commands from above. As a brilliant quote by William Gibson, perhaps the most famous author of cyberpunk novels, goes: ‘The future is there [...] looking back at us. Trying to make sense of the fiction we will have become’.

249gr

Last year, on a February afternoon, the little DJI Mavic Mini 249gr drone I ordered arrived at my doorstep. Finally, I could touch the object that had intrigued me so much for such a long time.

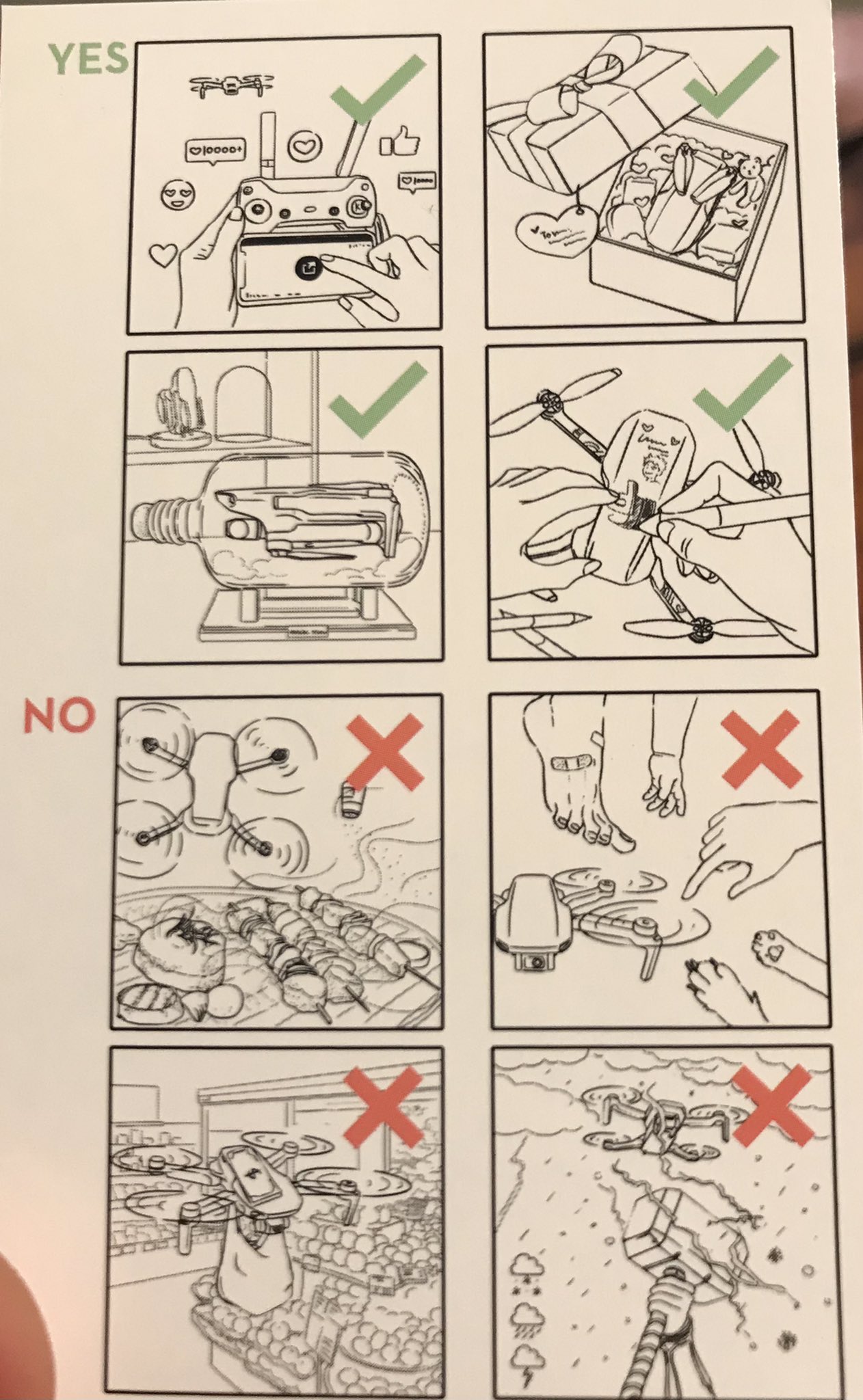

The weight of 249gr is to make sure I can fly the drone without the so-called flight license, as required by the European regulation in force as of December 31, 2020. All the other types of commercial drones, whether for recreational or professional purposes, from 250gr on need one. This type of small commercial drone is aimed at a young audience, presented as an agile and smart object. I remember being very amused by the instruction label which used pop culture language, for example reminding me that, yes, you can put the drone under glass instead of the old sailing ship, but, mind you! Better not use the drone’s propellers to cool the grill, or to let it do the shopping for you. LOL.

Enlarge

Actually, although the narrative around the DJI Mavic Mini is that of a fun and popular object, in reality, it is not a toy but an actual drone, a miniature UAV.

A few days later, with the help of a more experienced friend, I took my Mavic Mini for a ‘ride’ at the park nearby, where I had previously noticed other visitors flying their drones on more than one occasion. Although the area chosen for flight testing was isolated and cleared, the presence of the drone seemed, rather surprisingly, all in all accepted by the albeit few people present. Beyond the (relatively few) complications I had in installing and actually activating it, I immediately noticed the technological potential of this small object. Of that afternoon, I remember, above all, a feeling of wonder.

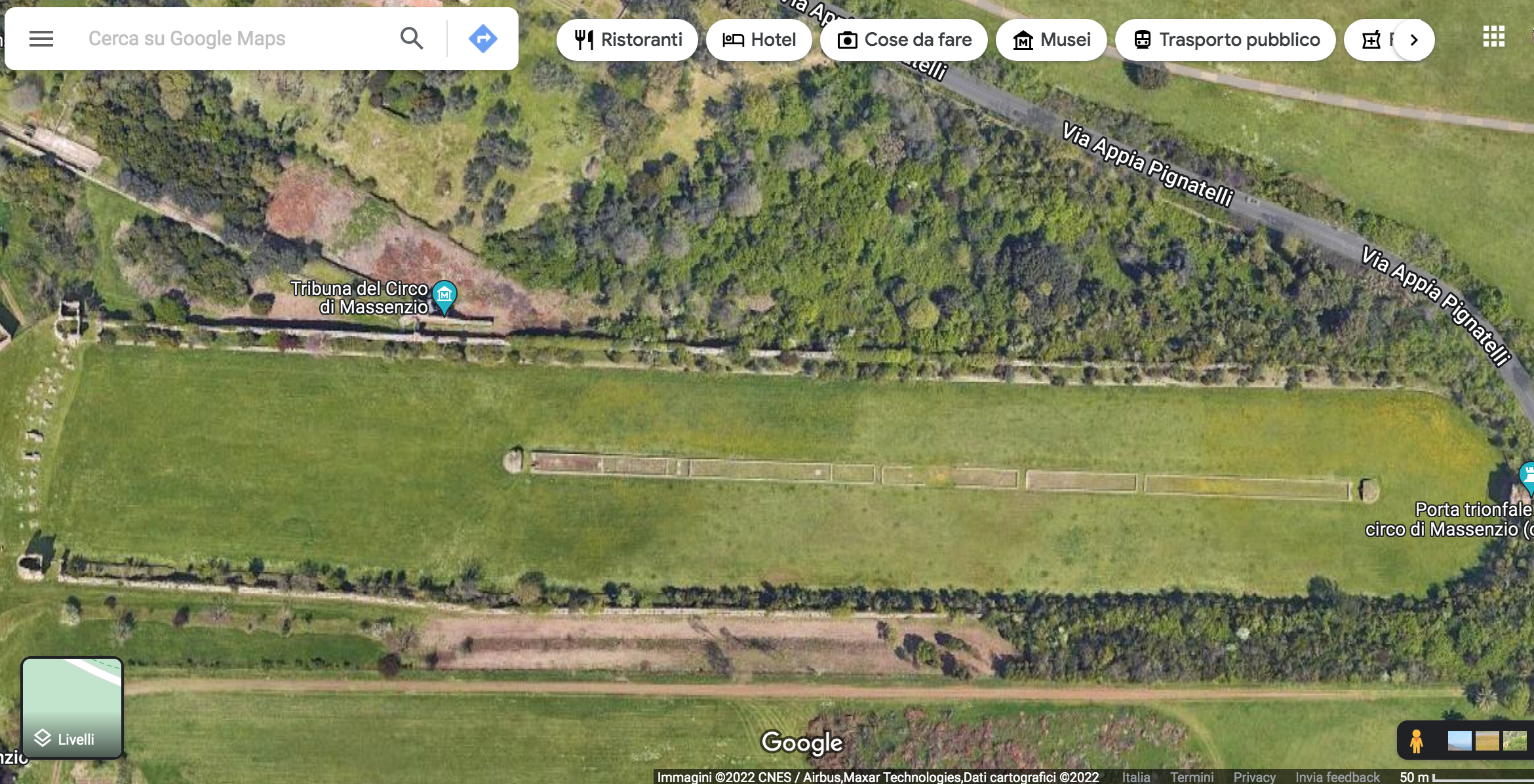

In fact, after a series of attempts with small flights, my friend and I decided to fly the drone a little higher, a little further on. The area where we were staying is part of a larger regional park, within which there are also Roman ruins and historical monuments, some of which were right adjacent to our location. Behind us, a large wooded expanse bordered the area, beyond which passed a fairly busy road of cars. We could not imagine and comprehend, then, that a little further on an imposing and majestic Roman circus was located, excellently preserved and well-maintained, but closed and inaccessible for years because of interminable renovations. So it was a great surprise when, thanks to the little Mavic, we ‘discovered’ this hidden treasure, whose architecture and structure seemed designed specifically to be observed from above.

Of course, the design of the Circus of Maxentius can also be observed through satellite images, trivially even through a search with Google Maps. Experiencing it with the drone is something different because being able to move it through remote controls produces an inherent presence that is impossible to perceive through satellite images – although, perhaps, the photographic output might be quite similar. The Mavic's eyes became our eyes for a while, and we were in awe. And therein lies the power of the small drone.

Enlarge

Sensing the commercial drone

Nowadays, commercial drones have been cleared in our post-modern societies, more or less. We use them to shoot striking panoramas of nature, to wow guests at weddings, to have fun races (drone racing) and for the spectacular shows at public events. Not only that: they are very useful for mapping endangered territories, and transporting small objects to inaccessible places, essential materials in emergency situations.

Understood as a media and technological object, the drone carries a set of values and meanings that are important to address. Let’s think of its characteristic aerial perspective, the so-called bird-eye or God-eye perspective, and how this ties together, among other things, elements of wonder and elements of surveillance. I mentioned before how the wonder’s effect is especially related to the drone’s proximity condition, its presence, becoming for a while, as Marshall McLuhan said, an extension of man. On the other hand, one of the most obvious and self-evident features of the drone is its relation with surveillance. Considering not only the visual element but also the extractive or thermic element, for instance when using the drone to collect data concerning the temperature of environments, things, and people. A volcanic eruption to monitor, a weapons depot to destroy.

The drone is also a physical presence. The shadow of this flying object is projected into the ground, on sunny days. Its most typical feature is being in motion, it is able to move between gaps and scale heights. It can rotate on itself and around an object, and it can suddenly accelerate and suddenly brake. If large enough, or close enough to the human ear, its buzzing sound is quite unmistakable. During the flight, it scares local birds (usually pigeons, gulls, or crows), that flee in terror or attack it. Finally, recent research, such as the work of Julia M. Hildebrand, has shown how there might be an affective relationship between the drone object and its operator, as sometimes happens with other objects (for example, with cars), drone owners name their little technological friend, taking it out ‘for a ride’. Partly a toy, partly a pet.

Enlarge

The drone is not only an increasingly present object in our daily lives, but it shows, above all, the particular characteristic of being a ‘multi-sensory’ medium. This aspect is also evidenced by the evolution of the drone object itself: in the last decade it has been implemented by significantly increasing ‘sensory’ features, moving from ‘simple’ radio-drone to advanced technology, in terms of sensors and detectors.

For many experts, especially academics who have begun to question the relationship of drones in our society, such as Anna Jackman, Bradly L. Garrett, and Anthony McCosker, the drone is something ‘more than optical’ and it creates ‘forms of “non-human sensing” that come together to form more-than-human ‘sensual amalgamations’. Daniela Agostinho, Kathrin Maurer, and Kristin Veel argue that ‘the drone is representative of “synesthetic media technologies” that combine a plethora of sensing modes to produce multisensory knowledge in human and nonhuman terms’. A drone is thus a hyper-sensory object, which not only translates but amplifies and extends human senses.

Yet, this sensory, translated into the cold materiality of its plastic or carbon fiber components, makes the drone nothing more than a simulacra of the senses, externalized and anesthetized. As Baudrillard wrote in his masterpiece work, L’Échange Symbolique et la Mort:

"The great simulacra made by men move from a universe of natural laws to a universe of forces and tensions of forces, today to a universe of binary structures and oppositions. [...] Cybernetic control, generation by models, differential modulation, demand/response feedback, etc.: this is the new operational configuration [...] At the edge of an ever-increasing extermination of references and purposes, of a loss of similarities and designations, lies the digital and programmatic sign, whose value is purely tactical, at the intersection of other signals (information corpuscles/tests), and whose structure is that of a micromolecular code of command and control."

And further:

"McLuhan's formula: “Medium is Message”. It is actually the medium...that governs the process of signification. One can understand why McLuhan saw the era of large electronic media as an era of tactile communication. (...) At the moment when touch loses its sensory, sensual value (“touch is an interaction of the senses rather than a mere contact of the skin and an object”) it is possible for it to become again the pattern of a universe of communication - but as a field of tactile and tactical simulation."

For Baudrillard, current communication, the one of the electronic media age, is tactile and tactical. Tactile as an interaction of senses, and tactical as an operational configuration, of command and control. Applying these words to the drone, note how being a hyper-sensory object, with human and non-human sensing, has, actually, an operational configuration – and in this sense, is a simulacra.

The genesis of the drone is mainly related to being a tactical tool. Chamayou reports how, in using military drones in counterinsurgency operations, ‘the use of drones shows all the characteristics of a tactic - or, more precisely, of a technological element - that is being substituted for a strategy’. Chamayou also argues that choosing the technological element over the strategic element highlights how in a state apparatus context, the practical-operational element is preferred to the programmatic element. The police apparatus is preferred to the military apparatus. In doing so, the political element is emptied, and replaced by the technological one. During the pandemic - and especially during lockdowns– we have witnessed this shift.

Lockdown and melancholy

The outbreak of the Covid19 pandemic has inevitably marked a before and an after in countless ways, including the way in which the global lives of citizens have become even more intertwined with communication technologies. This certainly applies to social media, video conferencing platforms and e-commerce platforms, but also to drones.

In Italy, during the most severe lockdown, police drones monitored and tracked those who ‘dared’ leave their homes, perhaps to simply go outdoors, stand in the sunlight. Those who ‘dared’ to reactivate and enjoy their senses, after being numbed by long months of lockdown and social distancing. In the U.S., police drones were used to measure the temperature of citizens and verify actual distancing.

Or, during lockdown in China, in an increasingly dystopian and apocalyptic escalation, drones themselves gave people orders to stay indoors.

Enlarge

At the same time, we have also momentarily delegated our senses, atrophied in fear of pandemic death, to these little flying robots. The small drones replaced our eyes, to ‘inhabit’ the usual places when they were interdicted; our arms, to take the dog out for a walk; and even our hearts, to ask the girl we like on a date.

Another element that emerged during the pandemic regards the atmosphere of mourning captured by the drone's eyes. This atmosphere unfolded in front of us in a rather literal way, when the ‘eyes of the drones’ captured the mass graves of the victims of the virus. Casualties were often more than reported in the official numbers and therefore were buried in mass – in some cases without accurate reporting by governments. In these cases, the images captured by the drones provided a visual testimonial of the severity of the pandemic situation, [see examples 1, 2 & 3].

The eyes of drones on grim empty cities, witnesses to loss and mourning.

In an insightful dialogue published in Filmquarterly, on April 2020, Caren Kaplan and Patricia R. Zimmermann reflect on this specific drone gaze, describing it as a true “genre”, a “spectacle of distance and melancholy”. For the authors, drone footages of cities in lockdown evoke a “wistful nostalgia for what has been lost”, both in time and space. The drone brings back grief that is not contingent on the pandemic moment alone, but structural to the “material conditions of neoliberalism to globalization”. It brings back deserted streets, but only for those who can afford to observe these same streets in the warmth of their homes. Essential workers, homeless people, and many others actually remained in the “empty” city. The physical distance of the drone, reports and reproduces social division.

Distance is another prominent feature of the drone. At a first glance, this might seem contradictory to the notion of proximity. But if proximity is “the state of being close to someone or something in space or time” (Oxford Dictionary), then detachment, albeit minimal, is always implied. That element of detachment, minimal but inescapably ever-present, makes the condition of proximity possible. By rising in the air, the object-drone creates a distance – between the drone and the operator, and also between the objects visually captured from above and the screen where we monitor those objects. The drone pushes back to us the perception of detachment. And this detachment, this emptiness that cannot be filled, creates the melancholic atmosphere typical of the drone. This is not the result of something that has “been lost”, but rather the feeling of something that was never, and will never, be achieved.

Asymmetric violence

If the melancholic atmosphere is a typical drone trait, so is its connection to violence. And it starts from its inherent asymmetry.

Physically and symbolically, the drone is placed above, and from above it commands, noticing things that those below cannot see. The drone, says Chamayou, whether military or commercial, always contains within itself an asymmetry all to the detriment of the subject below, which also shapes and produces the perception of the surrounding space. This change in perception inevitably involves the sensory dimension, both in those who control the drone and in those who, instead, experience its presence from below.

As a drone operator, how do I perceive the space around me through my hyperized senses, through my ‘additional and extended eye’, which I can control and monitor by remote? As my sphere of action and view expands, I often become aware of elements I was completely unaware of, and as a result, the environment around me takes on a different kind of meaning.

Unlike military drones, civilian or toy drones must necessarily be operated in close proximity to the operator. Therefore, the extended perception of the territory occurs in the same portion of space (with a variable extendable range, depending on the drone model and the characteristics of the territory) and extends the operator’s senses in real-time. This aspect, noticeable by anyone who has used a drone even once, is not necessarily evident if one only looks at the drone footages that we are used to see online, on television, on movies, etc. The moment we step into the shoes of the operator and no longer just of the viewer our perception of space changes, and so does our awareness of it.

However, it is even more interesting and important to understand how the perception of space changes when I experience the presence of the drone from below, that is, when I see one or more drones flying over my head. Let’s get in the shoes of the subject on the ground, the one looking at the drone in flight. Probably, the reactions will be different if the drone is used to locate survivors of a climate disaster, such as an avalanche in the mountains, than when it is used by the police during protests [see also].

What both situations – the survivor of an avalanche or the citizen targeted by police’s drone during a protest – have in common is that those who are on the ground do not really know who is flying that drone and why, and what kind of information or actions they want to obtain or perform. This, inevitably, will lead to have, even in the best of intentions and situations, an experience of space as a trap, a place circumscribed by the drone's moving frame, within which you are.

This asymmetry induces, in both top-down and bottom-up perspectives, a perceptual re-modulation of space and surroundings. Observing space is important because, as Achille Mbembe reminds us, space is ‘the raw material’ of the violence of sovereignty, as well as “the way in which the power of death operates”.

In his text The Politics of Verticality, Eyal Weizman highlights how “since the 1967 war, when Israel occupied the West Bank and Gaza Strip, (…) the Occupied Territories were no longer seen as a two-dimensional surface, but as a large three-dimensional volume”. The airspace and underground space became areas of control, thus creating vertical, “three-dimensional borders” which “redefined the relationship between sovereignty and space”. When the vertical dimension is added to the horizontal dimension, this generates a “proliferation of the sites of violence... [and] even the borders of airspace are divided between lower and upper layers. The symbolism of being on top (of those who are higher) is reiterated everywhere”. The characteristic elements of drone technology, being placed above, and its inherent asymmetry, contribute to reshaping space and our perception of it, producing and multiplying new forms of violence and control.

Enlarge

Moving in the (air)space

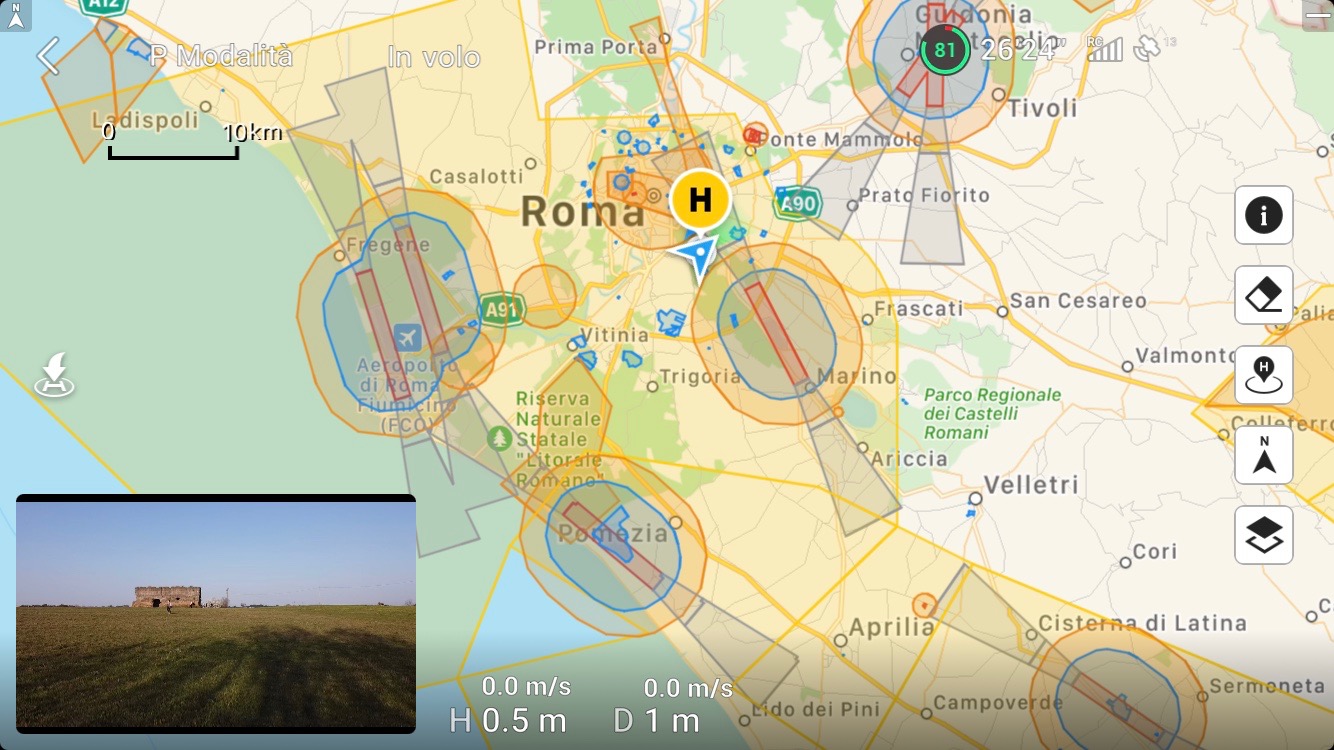

Recently, I flew my drone again and my first thought went to the issue of space. Where can I safely fly the drone? Which locations are shown on the DJI map? Where do I not bother people and animals? In which environment can I fly the drone without it getting damaged or entangled somewhere – as in tree branches or infrastructure? I was looking for “the perfect place”.

In the end, I happened upon the usual park near my home, which was safe enough in regards to people, animals, and the local environment, yet lacking a bit in “originality of perspective”. In fact, beyond the beautiful landscape views, I started wondering what it would be like to deal with different environments, perhaps with a bit more population. How would they look to my eyes, like little dots? Could I observe social patterns from above? As I was asking these questions, I realized how my desire for a change of perspective was a reflection of the God-eye drone feature. I wanted to see things from above, but static landscapes were no longer enough: I wanted to see people, motion. I wanted to observe life from above.

In moving the drone through space, coordination plays a key role. The gaze must monitor both the screen that replicates what the drone sees from above as the object-drone itself, and how it moves in the surrounding environment. This task is far from obvious and becomes gradually more complex as the environment itself becomes more complex. It demands effort in focus – that’s why flying a drone should require at least two pairs of eyes, and never just one.

Space is the terrain of the political. In his masterful text, La production de l’espace, Henri Lefebvre highlights how space is not an ‘empty’ environment ready to be filled, but a social environment produced by the relations and interrelations of different actors and elements, including institutional and economic practices, everyday experiences, and imaginaries. In a capitalist society, the goal is to dominate space, to control it, in order to maximize profits. This has obvious consequences and affects how people and citizens structure their daily-base existences.

Following Lefebvre, and embracing the idea that space not only stretches horizontally but also expands vertically, drones fit in. For Caren Kaplan, drones can play a role in the design and production of airspace - which is also shaped through infrastructure, dominated by regulations, and structured on the basis of ownership relationships.

"Airspaces are produced by assemblages of human and machine and can be apprehended through a broad array of material objects, elements, infrastructures, practices, and operations. (…) In a society structured by property relations, airspace is organized most dominantly by law and regulation (…). Over the decades of the twentieth century, what was first deemed to be a clear-cut case of ownership of the unending open space above the terrain and buildings that one owned became understood as volumes of space that could be carved up and claimed by municipalities, nations, militaries, and international bodies. Thus, it should not surprise us that (…) governments paid close attention and began to restrict and close airspace to citizens."

Drones have been used, and are still being used, by police and border control to control and restrain airspace and pursue forms of violence. Kaplan continues:

"When unarmed people on the ground face surveillance and/or weaponized attack from the air during such conflicts, access to airspace ranging from the right to clean air to breathe to the right to enter and fly objects in the atmosphere become vital elements of atmospheric politics and governance."

Thus, access to airspace has to be claimed, also through resistance practices emerging in the vertical dimension. Here, drones could also play a role, not only in practices but also in the re-design of airspace. Using drones to claim airspace can be an opportunity for resistance, says Kaplan, but it presents limits and ambiguities at the same time. That’s it: “in claiming or reclaiming airspace, we would do well avoid replicating settler colonial and nation state versions of the skies above our heads”. And to do that, better to start from the bottom, rather than from the top.

Enlarge

Droning our perception on the verge of the catastrophe

Drones are complex objects, on the one hand, they seduce us and have the ability to extend and expand our senses. On the other, they produce complex spatiality and reproduce hierarchies, echoing the violence and the melancholy of our capitalist society, the terror of postmodernity.

The condition of proximity is the most important element of the commercial drone, bridging together distance and connection within the surrounding environment. When we fly a commercial drone, our senses are engaged in coordination activities, expanded and hyperized through the experience of the bird-eye view and, sometimes, also through additional features that go well beyond human senses. Yet, the drone is nothing more but a simulacra of those senses.

The condition of asymmetry is not only inherent to the military drone, but to the commercial drone as well. When we fly the drone, the space is a controlled environment, when we experience it from the ground, the space becomes a trap. This is due to a kind of “unpredictability” of the drone. A drone can move very fast: one moment you see it flying over your head a few meters away, and the next moment it pops up behind your back, catching you by surprise. That feeling of manhunt doesn’t really go away. In his text, Postscript on the Societies of Control, Gilles Deleuze wrote:

"Types of machines are easily matched with each type of society – not that machines are determining, but because they express those social forms capable of generating them and using them. The old societies of sovereignty made use of simple machines – levers, pulleys, clocks; but the recent disciplinary societies equipped themselves with machines involving energy, with the passive danger of entropy and the active danger of sabotage; the societies of control operate with machines of a third type, computers, whose passive danger is jamming and whose active one is piracy and the introduction of viruses. This technological evolution must be, even more profoundly, a mutation of capitalism."

What social forms does the commercial drone express? With what type of society does it match? The technological evolution represented by the drone, corresponds to what mutation of capitalism?

Mark Fisher argued that “capitalism is what is left when beliefs have collapsed at the level of ritual or symbolic elaboration”, and describes our times with the term capitalist realism, where “‘real’ means the death of the social”. For Fisher, Capitalist realism is “like a pervasive atmosphere”. Climate change and environmental catastrophe, abysmal social and economic inequality, systemic racism, never-ending wars. We are now beyond the society of control, beyond even capitalist realism. We are inside a society on the verge of apocalypse, generated by voracious, predatory capitalist acceleration. In Fisher's words, a rapacious, indifferent, inhuman capitalism.

In the end, the drone is violent and melancholic as our societies are. It is violent in its asymmetry, reminiscent of overpowering. It is melancholic because that overpowering will not guarantee salvation, at best only survival.

Enlarge

Gaia Casagrande is a Postdoc Research Associate at the Department of Social and Political Sciences at Milan University, where she works on the ERC project ‘CRAFTWORK: Understanding the relationship between identity and work in the context of the future of work’. Previously, she obtained her Ph.D. at Sapienza University of Rome, and was visiting Ph.D. and GTA at the Department of Digital Humanities, King's College London. Her research interests mainly concern the social implications of new technologies, and critical theory. In detail, her studies focus on platform studies, digital labor, social movements and media activism, drones’ studies.

—

References list

Daniela Agostinho, Kathrin Maurer & Kristin Veel, ‘Introduction to The Sensorial Experience of the Drone’, The Senses and Society, 2020, 15:3, 251-258.

Jean Baudrillard, L’Échange Symbolique et la Mort, Gallimard, Paris, 1976.

Walter Benjamin, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, Illuminations, Ed. Hannah Arendt. Trans. Harry Zohn, New York: Schocken, 1969.

Joel M. Carter, and Samuel Woolley, ‘We Need to Know Who's Surveilling Protests—and Why’, Wired, 3 November 2020, https://www.wired.com/story/opinion-we-need-to-know-whos-surveilling-protests-and-why/.

Grégoire Chamayou, Théorie du drone, La Fabrique, Paris 2013.

Nick Couldry, Media: Why it Matters, Cambridge: Polity Press, 2020.

Gilles Deleuze, Postscript on the societies of control, October, Winter (59) (1992), pp. 3-7.

Vikram Dodd, ‘Drones Used by Police to Monitor Political Protests in England’, The Guardian, 14 February 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2021/feb/14/drones-police-england-monitor-political-protests-blm-extinction-rebellion.

Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative?, Zero Books, UK, 2009.

Bradly L. Garrett, and Anthony McCosker, ‘Non-human Sensing: New Methodologies for the Drone Assemblage’, in Edgar Gómez Cruz, Shanti Sumartojo, and Sarah Pink (eds) Refiguring Techniques in Digital Visual Research: Digital Ethnography, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017, 13–23.

William Gibson, Pattern Recognition, Penguin, New York, 2003.

David Hambling, ‘What are drone swarms and why does everyone suddenly want one’, Forbes, 1 March 2021, https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidhambling/2021/03/01/what-are-drone-swarms-and-why-does-everyone-suddenly-want-one/?sh=3191a1342f5c.

Julia M., Hildebrand, ‘Consumer Drones and Communication on the Flight’, Mobile Media & Communication, 2019 Vol. 7(3), pp. 395–411.

Anna Jackman, ‘Sensing’, Society for Cultural Anthropology Editor’s Forum: Theorizing the Contemporary, 27 June 2017, (https://culanth.org/fieldsights/sensing).

Caren Kaplan, ‘Atmospheric Politics: Protest Drones and the Ambiguity of Airspace’, Digital War, 2020, pp. 50-57.

Achille Mbembe and Libby Meintjes, ‘Necropolitics’, Public Culture 15.1 (2003): 11-40.

Henri Lefebvre, La production de l’espace, Anthropos, Paris, 1974.

Eyal Weizman, ‘The Politics of Verticality’, Open Democracy, 23 April 2002, (https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/article_801jsp/).

Patricia R. Zimmermann, and Caren Kaplan, ‘Coronavirus Drone Genres: Spectacles of Distance and Melancholia’, Filmquarterly, 30 April 2020, https://filmquarterly.org/2020/04/30/coronavirus-drone-genres-spectacles-of-distance-and-melancholia/.