Philanthropy is on the rise in the Dutch visual arts. Fat cash prizes, big-name exhibitions, large-scale renovations, spectacular public artworks, and big scandals are changing the public display of art and undermining the democratic governance of art institutions. While some have critiqued the patron's rise to power, the majority of the art world remains silent, muted by a combination of ignorance and self-censorship. How can we overcome this deadlock and start cultivating a healthy public debate?

A ‘Totally Irrelevant’ Enumeration

In 1994, De Appel in Amsterdam founded its Curatorial Programme, the first-ever educational program for curators. Today, the CP is a widely renowned institution, with graduates in leading positions at art institutions around the world. From 2013 to 2019 and 2022 to 2024, the Curatorial Programme received long-term financing from the philanthropic fund Ammodo. Since 2020, the philanthropic Hartwig Art Foundation has also provided structural support to cover part of the operational costs.

In 2010, Voordekunst, the first non-profit cultural crowdfunding platform globally, was founded in The Netherlands. Voordekunst allows artists and creatives to ask small donors to help make a project come true. In practice, many of the donations are made by family and friends. In recent years, however, Voordekunst has developed a match-funding strategy to connect creatives to bigger sponsors. Creatives are connected to a cultural fund that agrees to contribute the remaining 25% once the creative has raised approximately 75% of their goal. Dutch public funding bodies that have participated in match-funding on Voordekunst include the Amsterdam Fund for the Arts, the provincial government of Limburg, the provincial government of Gelderland, Almere Cultural Fund, Groningen Art Board, the Rotterdam municipal government, and the Mondriaan Fund. Private funds also play an important role in match-funding through Voordekunst: in 2021 and 2022 alone, the Prins Bernhard Cultuurfonds gifted over 28 million euros through the ‘Long Live Giving’ program. In total, fund-matching has contributed to 3,337 projects – just over half of the 6,527 campaigns that have been successfully financed via Voordekunst.

Every two years, since 2012, the Niemeijer Fund awards the Theodora Niemeijer Prize to a mid-career female artist. So far, Sarah van Sonsbeeck, Sachi Miyachi, Sissel Marie Tonn, Josefin Arnell, Silvia Martens, and Sara Sejin Chang have each received a cash prize of €100,000. The Niemeijer Fund has also commissioned the Boekman Foundation to create a research report on the position of female artists in The Netherlands. The fund’s assets come from the estate of its namesake Theodora Niemeijer, daughter of Theodorus Niemeijer, one of the biggest tobacco manufacturers in the 19th century in The Netherlands.

In 2012, the private British Outset Fund created a sister organization in the Netherlands. Outset connects individual, mid-tier patrons with high-quality experimental art productions. For instance, with the support of Outset NL in 2018, Matilde Cassani created the art piece Tutto: Ordine e Disordine, a literal eruption of confetti during Manifesta 12 in Palermo. Outset also supported the production of Alexis Blake’s performance artwork rock to jolt [ ] stagger to ash in 2021 at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, which was later awarded the Prix de Rome.

In 2013, Casco Art Institute in Utrecht founded the Arts Collaboratory – ‘the most important network of art institutions that you’ve never heard of,’ according to ArtReview. The Arts Collaboratory is a community of 25 arts organizations, primarily from the Global South, which is committed to forging long-term, reciprocal relationships across borders. An important aspect of this collaboration is a jointly managed fund called the ‘common pot’. The money in this pot was initially donated by the humanist fund Hivos and the DOEN Foundation, which distributes lottery funds to social causes. After several years, Hivos stopped its support, but DOEN and Casco Art Institute continue their collaboration up to the present day.

On September 10th, 2016, the Voorlinden Museum was opened in Wassenaar. It consists of a 4,000-square-meter building and a large sculpture garden, filled to the brim with works from the Caldic Collection. Many of these works are site-specific pieces by prominent artists, specially commissioned for the museum. There is a light installation by James Turrell, a pair of mice lifts by Maurizio Cattelan, and a COR-TEN steel installation by Richard Serra. Swimming Pool by Leandro Erlich is especially popular on social media: the blue cubical space with a ladder and a glass ceiling, which looks just like a real swimming pool, is highly photogenic. Voorlinden and the Caldic Collection are owned by the chemical industry tycoon Joop van Caldenborgh.

On October 17th, 2017, it was announced that the international star curator Beatrix Ruf would resign as director of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. During Ruf’s three-year tenure, the Stedelijk presented several high-profile exhibitions featuring blue-chip artists like Isa Genzken, Jordan Wolfsen, and Ed Atkins. Nevertheless, the Board of Directors decided to let Ruf go, effective immediately, due to an apparent conflict of interest. Aside from her well-paid full-time job at the museum, Ruf held twenty ancillary functions that she had failed to report to the museum and owned a consultancy firm that made a profit of at least €437,000 in 2015. Ruf had made this money advising art collectors, including collectors who had donated works to the Stedelijk Museum. An independent investigation commissioned by the Amsterdam Municipality later concluded that Ruf was not guilty of a conflict of interests, but that she should have been more transparent.

In August 2019, the Boijmans van Beuningen Museum in Rotterdam closed its doors for seven years for a major renovation to remove asbestos and build a new entrance. The costs were estimated at €223.5 million. €168.9 million was contributed by the municipality of Rotterdam. The additional millions would have to be funded privately. Wim Pijbes, director of the philanthropic foundation Droom en Daad, offered a gift of €80 million. In addition to funding the renovation, this donation was meant for a new ‘Boijmans Modern’ museum in South Rotterdam. One of the conditions was that Droom en Daad would get two seats on the museum’s board of directors. The museum and the municipality refused to accept this demand, and the donation was rejected. In the following years, the estimated costs of the renovation rose to at least €259 million due to setbacks, and the reopening was tentatively postponed until 2029. In the process, a chronic conflict arose between the museum, the architects, and the municipality. Museum director Sjarel Ex stepped down, and the renovation ground to a standstill, but municipal officials continued working on the project and charging for their time, which caused the budget deficit to run up. At the moment of writing, in March 2024, there is no end in sight to the misery of the Boijmans.

The building of the future museum on the Amsterdam Zuidas, in development by the Hartwig Art Foundation.

In September 2021, it was announced that a new museum for contemporary art would open its doors in Amsterdam – in addition to the already existing, publicly funded Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam. The Amsterdam Arts Council and the City Council agreed to a plan made by the philanthropic Hartwig Art Foundation to develop a new, 'cutting-edge international museum' in the Zuidas area. The two-person board of the Hartwig Art Foundation consists of Beatrix Ruf and Rob Defares, philanthropist, collector, and former member of the Supervisory Board of the Stedelijk Museum. The museum will be housed in a former courthouse, which the Amsterdam Municipality will purchase for this purpose from the National Real Estate Agency for €26.8 million. In response to this 'gift to the donor', one patronage expert commented: ‘This is all too cheeky: an ex-board member of the Stedelijk Museum wants to start a private museum with the support of the Amsterdam Municipality, which will compete with the Stedelijk.’

On November 5th, 2021, King Willem-Alexander officially opened the Boijmans Depot, the Boijmans van Beuningen Museum’s new art depot building. The simple shape (which reminds many people of a plant pot) and the mirror cladding of the imposing building immediately gained international renown. The building of this depot is the result of a ‘unique public-private collaboration,’ according to the museum’s website. In addition to a contribution from the Rotterdam Municipality, the philanthropic foundation De Verre Bergen contributed €27.6 million to the construction.

As of April 2022, a beautiful former underground water basin in Delft can be visited by the public. It is the exhibition space of Radius, Center for Contemporary Art and Ecology. The property is owned by real estate developer Robert Lekkerkerk, the father of founding curator Niekolaas Lekkerkerk. The location was renovated by Lekkerkerk Senior’s real estate firm and has been rented to the art organization for a friendly price ever since. On July 10th, 2023, it was announced that the Mondriaan Fund would provide €110,000 in yearly support for Radius for two years, consolidating the public-private collaboration.

On July 2nd, 2023, the statue Moments Contained by Thomas J. Price was unveiled on the Stationsplein in Rotterdam in the presence of State Secretary for Culture Gunay Uslu. It’s a larger-than-life bronze statue of a Black woman, standing confidently in the middle of the square, with her clenched fists in the pockets of her tracksuit bottoms. The public’s response was universally positive. Moments Contained, it was said, became an ‘instant Rotterdam icon’. The statue was gifted to the city by the philanthropic foundation Droom en Daad.

In April 2023, two high-intensity ‘listening sessions’ took place at the Stedelijk Museum, in which critical thinkers and artists made proposals for the future of the institution. These sessions were the inauguration of Buro Stedelijk, an experimental place for art that operates as an independent department of the Stedelijk Museum. The museum offers Buro Stedelijk space within its premises. Long-term funding for the staff and programming is donated by the founding partners Fonds 21 and Ammodo.

On July 14th, 2023, the Dutch Photography Museum in Rotterdam announced big news. Thanks to a gift of €38 million from Droom en Daad, the museum acquired a huge former industrial building in Rotterdam and planned its renovation into a museum space. Birgit Donker, the director of the Photography Museum and former director of the public Mondriaan Fund, was delighted with the new, larger building, where the museum will reopen its doors in 2025.

On July 16th, 2023, NRC reported that Martijn van der Vorm, the billionaire behind both Droom en Daad and De Verre Bergen, had donated no less than €793 million to causes in Rotterdam of his own choosing. This has led to a close relationship between his charitable foundations and the municipality. Droom en Daad and De Verre Bergen have direct access to the Rotterdam municipal executive via a special construction. They have also been exempted from the standard integrity investigations by the real estate department. However, there is a dark side to Van der Vorm’s activities. His investment firm HAL (Holland-America Line) has been dodging Dutch taxes for years. The tax evasion, however, hasn’t affected Van der Vorm’s warm relationship with the Rotterdam Municipality. According to Mayor Ahmed Aboutaleb of the Dutch Labour Party, the Van der Vorm family’s fiscal constructions are ‘totally irrelevant’.

Politics of Philanthropy

As someone who loves art and works in the Dutch visual art world, I’ve witnessed the recent rise of arts philanthropy with astonishment, annoyance, and – increasingly – anger. Martijn van der Vorm’s blatant art-washing, defended by the Mayor of Rotterdam, is a frontal attack on democratic governance. The implicit message is loud and clear: the rich know best what is good for society, and they should be allowed to provide public services without the intervention of cumbersome democratic systems of redistribution. Unfortunately, I’ve experienced how the public debate on this issue is subtly suppressed.

My engagement with the topic of arts philanthropy dates back to 2021. At the time, I was working for Platform BK, a Dutch art workers' representative organization. As part of our discursive program, we published an article by artist Timo Demollin titled ‘The Philanthropy Trap’. In this piece, Demollin discussed the disruptive position of three new philanthropic funds: Ammodo, Droom en Daad, and the Hartwig Art Foundation. Looking at these cases, he observes a shift in the role and position of arts philanthropy. Philanthropists are traditionally mostly interested in being part of high-profile success stories, such as the acquisition of masterpieces for prominent museums. But this new generation of philanthropists distinguishes itself by providing (long-term) financing to medium-sized, socially engaged, and critically minded art organizations. They don't mind if their money is used to cover running costs like salaries, buildings, and experimental programming instead of contributing to the purchase of yet another Rembrandt painting for the Rijksmuseum. At first sight, this development 'sounds good—the more money that goes to the arts the better,' Demollin writes, but at closer inspection 'it testifies to a creeping systemic rot'. Three decades of systematic budget cuts have made public art institutions increasingly dependent on patronage. This gives patrons more power in shaping the public display of contemporary art. They also get tax breaks and a free reputation boost in the process.

'The Philanthropy Trap' was very well-read and stirred some commotion. We received emails in support and messages from critics, and lively discussions arose on social media.1The people working at Hartwig Art Foundation, Ammodo, and Droom & Daad also read the article, though without making this known publicly. We were even contacted by the Dutch Association of Property Traders due to alleged misrepresentation of Dutch flash traders—the profession of Rob Defares, the patron behind the Hartwig Art Foundation. With his sharp and accessible piece, Demollin had in one fell swoop made the rise of a new patronage visible, understandable, and, therefore, debatable. He also offered a perspective for (collective) action: 'Artists, curators, and cultural workers would do well to unite wherever possible, beyond competition and self-interest, so that the art sector can collectively put a stop to the influence that philanthropists can exert on art.' At the same time, Timo had conjured a series of systemic questions it could hardly begin to answer: Which interests drive the rapid rise of visual arts patronage in the Netherlands? How is philanthropy changing the public display of art? And how does the increasingly complicated ‘mix’ of public and private money affect the power structures in the field?

It was therefore important to forge ahead and further encourage the public conversation about patronage. We decided to jointly organize a one-day symposium on the ‘culture of giving’ in the Dutch visual arts and called it The State of Patronage. This is when we first encountered the seriousness of the self-censorship around questionable money in the arts. We wanted to organize the symposium in collaboration with a (preferably small) art institution that receives philanthropic funding, to bring in their practical experiences and questions. Out of the dozen or so such institutions in the Netherlands, we approached the two with the most explicitly socially engaged program. Both institutions seriously considered our proposal, but, ultimately, didn't dare to host the symposium. Backing off, one of them explicitly expressed fears of 'patron bashing'. The Mondrian Fund, the national Dutch visual arts fund, which had been invited to join the discussion several times, also rejected participation and was very displeased with the symposium.

In the end, we collaborated with the contemporary art space Framer Framed, which hosted and fully supported the political vision of the event. On April 30th, The State of Patronage took place, bringing together most of the very few public thinkers who had substantially engaged with the issue of patronage in the Netherlands. 2Helleke van den Braber, professor of patronage studies at the University of Utrecht; Olav Velthuis, professor of sociology at the University of Amsterdam, specialized in the art market; Sofia Patat, who worked as a fundraiser and business director for large and small art institutions and has written about this in several publications; patronage expert Renée Steenbergen; and Roel Griffioen, a researcher and activist who has written multiple articles on the topic of ‘real estate patronage’. These experts discussed the topic with each other and with artists, representatives of institutions and public funds, and, of course, private donors.3Liesbeth Bik, artist and chairperson of the Dutch Academy of the Arts (Akademie van Kunsten); Kristel Casander, director of Voordekunst; Nous Faes, sociologist, policy advisor, and opinion maker in the visual arts; Yvonne Franquinet of the Amsterdam Art Fund (AFK); Marjolein de Groen of Collectie DE.GROEN; Stephanie Schuitemaker, director of Outset; and Steven van Teeseling, director of Sonsbeek and State of Fashion.

The result we aimed for was an intense, critical, but constructive conversation between various stakeholders to map out patronage's current and ideal role. In the end, the event was both interesting and frustrating. Jack Segbars wrote in his report:

The State of Patronage made it clear that there is much confusion concerning roles among stakeholders in positioning, valuing, and supporting the arts. Therefore, productive and disruptive practices of patronage exist side by side in an amorphous totality that prevents any assessment of accountability, equity, or democratic values. As a result, disruptive donors have free reign, recipients of donations are at the mercy of arbitrariness, and responsible donors – who are needed to keep the art sector afloat – unintentionally end up being seen as suspect.

We were getting close now. The fundamental role confusion between stakeholders had become clear. However, in questioning the role of arts philanthropy, our goal was never to construct a disinterested description of the situation but to cultivate an explicitly political discourse on arts philanthropy in the Netherlands. Once again, it was clear to me that the public debate needed another push. To this end, I have collected texts by participants of the symposium into a little book, called ‘The Liberation of Arts Philanthropy’, and written an introduction and conclusion to accompany the contributions. In a final effort, I have tried to go beyond role confusion and formulate a series of productive talking points towards a politics of philanthropy. You are currently reading the translation of these companion texts, and the six theses below are the major lessons from two years of research – drawing, ethical, and political conclusions.

Thesis 1: We need a political discussion about patronage that transcends moralism

Often, discussions about patronage get bogged down in moral wrangling between critics and pragmatists. Critics denounce that wealthy patrons or corporations impose their individual tastes on the public, especially if the money was donated by dubious parties such as arms traders, plantation agriculture companies, the fossil industry, betting companies, or flash traders. These critiques, however, are not very effective in convincing proponents of patronage, who in turn put forward a wide range of pragmatic arguments. According to them, patronage is simply necessary to survive as a cultural organization or creator.4It is striking that pleas for a major role of patronage often coincide with government cutbacks (2004, 2012) or other kinds of budgetary crises for culture (like the coronavirus crisis in 2020-2022). In 2004, during a symposium at the Amsterdam Stadsschouwburg, State Secretary of Culture Medy van der Laan stated: 'The government has less money to distribute and therefore we have to make choices. But even if we did not have to make cuts, I would make a strong case for patronage. It is always better for the arts if more groups in society feel involved.' Unlike his predecessor, State Secretary Halbe Zijlstra, who cut the entire cultural budget by one-third in 2012, did explicitly draw a connection: in his view, the retreating government would make room for patronage to step in. Rob Gollin and Joost Ramaer, ‘Weldoenders gezocht’, Volkskrant, 9 September 2004, https://www.volkskrant.nl/home/weldoeners-gezocht~badf3f49/. It is allegedly hypocritical to accuse patrons of exerting power, while governments also create strict frameworks for art production (diversity, inclusion, and regional distribution are often the order of the day – along with the high regulatory pressure that this entails). And as long as nothing illegal happens, people in the cultural sector should stop judging each other.5This argument against regulatory pressure is often brought up as a call for renewed trust. Martijn van der Steen, special professor of public administration at Erasmus University, for example, called for less bureaucracy and a more horizontal organization of the field during the Paradiso Debate 2023 organized by Kunsten '92. However, it remains unclear how reducing the regulatory burden without redistributing power and resources would lead to a more horizontal organization instead of perpetuating the prevailing order. 'Paradiso Debat 2023', Platform BK, 4 September 2023, https://www.platformbk.nl/paradiso-debat-2023-2/. Let's look on the bright side; these proponents say: private donations are the ultimate sign of commitment at a time when support for culture is eroding.

These sophisticated, pragmatic arguments make it possible for even a seemingly simple ethical issue to be brought to a head. A good example is the fossil industry's sponsorship of arts and culture. After years of campaigning by Fossil Free Culture NL, most Dutch arts organizations have banned fossil sponsors, and a consensus seems to have formed in 'the sector'.6Zoë Dankert investigated the state of fossil funding at Dutch museums in 2020. She found that, at that time, there were only four museums left in the Netherlands with fossil sponsorship: the Drents Museum (NAM), Groninger Museum (Gasunie and GasTerra), NEMO (Shell), and Rijksmuseum Boerhaave (Shell). After the publication of the article, NEMO cut its ties with the fossil industry (it is not likely that the article was the deciding factor for this decision). Zoë Dankert, ‘Kunst & Klimaat: De lange arm – wat zoekt de fossiele industrie in de kunst?’, Metropolis M, 16 September 2020, https://www.metropolism.com/nl/features/41737_kunst_klimaat_de_lange_arm_wat_zoekt_de_fossiele_industrie_in_de_kunst. Yet the Groninger Museum still has itself structurally sponsored by the state-owned fossil fuel companies Gasunie and GasTerra. While the earth under the people in Groningen was being drilled to pieces to extract natural gases, museum director Andreas Blühm claimed to be proud of his partnerships with these ‘pioneers in the energy transition’. However ethically tone-deaf or factually incorrect he is proven to be, Blühm is not receptive to moral appeals from the field.7For years, Fossil Free Culture Groningen has been campaigning against the museum’s sponsor deal. They were joined by artist Marit Westerhuis, who called out the Groninger Museum during the opening of her own solo exhibition. I’ve been commissioned by art space Het Resort to write a Dutch-language article about this case: Sepp Eckenhaussen, ‘De slag om het museum: Een ode aan klimaatactivisten in de kunst’, Dagblad van het Noorden, 2 January 2023, https://dvhn.nl/cultuur/De-slag-om-het-museum-28135228.html. So, no, an informal moral consensus is not enough.

It is also important to note that more ‘extreme’ industries, such as the weapon industry, may seem distant from the art world, but that is not always the case either. Museum Moore in the Dutch town of Ruurlo displays a collection of (neo)realist art. The museum and its collection (largely built up from the integrally acquired art collection of former banker Dirk Scheringa) are owned by the estate of the late chemical magnate Hans Melchers. Melchers was convicted in 1986 of supplying the Iraqi government with chemicals that could be used to make chemical weapons. A civil lawsuit based on the same allegations was pending against Melchers until he passed away in 2023. Historical links between patronage and the arms industry are also prominent. The Prince Bernhard Culture Fund (which recently changed its name to the simple ‘Culture Fund’) was established in London in August 1940 under the name Spitfire Fund, aiming to raise money for war materiel.

To avoid this kind of situation, which we could safely call ‘problematic’, Roel Griffioen has proposed that an ‘ethics of patronage’ ought to be constructed. He observed that ‘we are not used to demanding public accountability from private interests that are active in the public arena’ – but we should. It's surprisingly easy to imagine such norms: ‘Don’t take money from the arms industry’, or ‘Only work with real estate development if a sustainable place for art is guaranteed’. According to Griffioen, such public accountability ethics of patronage is ‘a minimum requirement to get a handle on the changing current moment. Public dealings demand public responsibility to prevent private interests from harming the public good.’

In a similar vein, Àngels Miralda Tena has described how an ‘ethical patron’ could carry part of the responsibility for upholding public accountability: ‘With a disappearing boundary between the private and public we all need to confront the question of how to promote social values in a world in which they are on the point of extinction. The role of the patron should not encourage this situation, but fight together with cultural actors against the elimination of public institutions.’ Tena’s definition of ethical patronage implies respect for the democratic principle that power over a publicly funded institution is not for sale. We can extrapolate that a patron does not belong on a supervisory board. Nor should owners of loaned artworks be able to interfere with exhibition policy in any way. Clearly, a special municipal steering committee for a philanthropic foundation is completely out of the question.

It is immediately clear that ethical patronage requires transparency. Public accountability is not possible until the full interest of a patron is entirely transparent and, to use Roel Griffioen’s words, the quid pro quo is clear. But who will be checking these interests in practice? Surely, this is not something we can expect of anyone who happens to visit or work with a patronage-funded art organization. Sofia Patat has proposed that we should look to the fundraiser in this matter. According to Patat, a good fundraiser with integrity has a sharp eye on which interests come into play, allowing them to be the pivot between the values of a cultural institution and the interests of the sponsor. At best, this person acts as a guarantee against art washing.

However, we should be mindful to rely on self-regulation. Such ethical discussion ‘on the ground’ can quickly lapse into pseudo-politics. This problem has plagued the Dutch cultural sector many times in the past. In these cases, well-meaning people set up a complicated process with working groups, assemblies, team outings, and soundboarding sessions. People seek and find consensus on what ‘we’ should think ‘as an industry’. But in the end, little changes in the distribution of power and resources. In the end, these projects only expose the false assumptions under ‘our’ pseudo politics: that people in the culture sector have a keen sense of morality. We know that, in reality, ethics are often ignored by people in positions of power – also in culture. It is, therefore, imperative that an ethical discussion on patronage be directly translated into a real political stance.

A good example of such a stance was given by US artist Andrea Fraser in her 2017 lecture in Cologne on ‘Trusteeship in the Age of Trump’. She criticized venture capital investor Steven Mnuchin’s membership of the Board of Trustees of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. Not only did Mnuchin make his fortune trading in home foreclosures, but he also took charge of fundraising for Donald Trump’s election campaign in 2016. Fraser considered Mnuchin's position untenable and wrote an open letter. She stated:

Since the late 1960s, the art field has seen waves of concern over the influence of trustees and patrons on museum programs and collections. Unfortunately, these concerns often ignore the broader structural conditions and consequences of the US system, which places responsibility for cultural institutions—and also many educational and social-welfare functions—with philanthropic organizations. These organizations are plutocratic in the most basic sense of the word: institutions that are considered public and provide basic social functions, but are governed by a minority of the wealthiest citizens according to their own interests, with little or no democratic input or oversight.

The letter, which several art world hotshots co-signed, proved effective. Mnuchin stepped down from the MOCA’s Board of Trustees in 2016. However, I believe that the real achievement of Fraser’s efforts goes beyond the tactical victory. By linking the critique of Mnuchin and the reliance on patronage to a critique of political systems, Fraser shows that the debate on patronage is not just about imposing taste or the question of what money is ethically acceptable. There is a direct relationship between patronage and the distribution of power and control. Studying the American context, Fraser observes that patronage contributes to the rise of plutocracy. Is this also happening in The Netherlands? Can we talk about the politics of philanthropy in The Netherlands without making the discussion personal, without self-censorship, without questioning intentions or taste?

Thesis 2: Patronage after the welfare state is a uniquely European phenomenon

Pragmatics often point out that patronage works in America (and should therefore work in Europe, too), while critics denounce the corporatization of museums as a dangerous type of ‘Americanization’. In September 2023, even a private fundraiser of Dutch debate center De Balie, Caroline Lapidaire, published an op-ed in a prominent newspaper titled ‘Stop the Americanization of the cultural sector’. Indeed, the corporatization of the cultural sector and the growing power of endowment directors show similarities with the situation in the US. However, the usefulness of measuring the Dutch cultural system up to the American standard is limited.

Back to Miralda Tena. She notes that a gift in Europe fundamentally differs from gifts in America. Almost all art institutions in the Netherlands were built with public funding or went through some form of collectivization (which happened to Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, Van Abbemuseum, Kröller Muller) after the Second World War. Therefore, the distribution of money and governance in the arts are, in principle, subject to democratic, transparent, and accountable processes. Miralda Tena concludes that arts philanthropy in Europe, regardless of intentions, by definition contributes to the ongoing undermining of the idea of culture as a public good:

The privatization of culture in itself is the most symbolic producer of alienation and elitism within the art world. It is also a uniquely European phenomenon. […] Other geographical contexts have not had the privilege to rely on stable state structures of cultural funding for longer periods of time. Organizations in the United States rely on private donations as a norm, and organizations such as Istanbul Biennial, supported by the Koç Family, have signed long-term agreements to continue private funding commitments. In these circumstances, private patronage is not only necessary but admirable in that it notices and fills a void which is simply not provided by the state.

The emergence of new forms of patronage in the context of the (crumbling) Dutch welfare state is, in other words, a typically European phenomenon, which raises a unique set of questions. Who decides what the public programs of art institutions look like, and what kind of art is collected by the Dutch state? To what extent is art a public industry worthy of public support? And what are the practical implications of the ideal of a ‘democratic’ art supply? Only by asking these questions can a geographically and historically sophisticated analysis of patronage emerge.

For instance, culture critic and policy advisor Nous Faes has linked emerging patronage in The Netherlands to the availability of structural tax avoidance methods. In her analysis, which is based on a research report commissioned by the Dutch Minister of Finance in 2022, she states:

Wealthy Dutch people [over the past 15 years] massively avoided tax via donations to charities set up by themselves, and there were even millionaires who paid zero euros in income tax due to their gift deduction. Thus, 66% of millionaires who made large periodic (= multi-year and legally fixed) donations were found to do so to a charitable organisation (ANBI) set up by themselves; of those with more than 25 million assets, 94% did so. Besides tax avoidance by siphoning off private assets, such as shares and paintings, having your own charity also offered opportunities to claim high expenses.

European patronage is thus characterized by a striking reversal: tax benefits such as exemption from income and corporate tax are a gift from society to the philanthropist. According to Faes, it is time to intervene politically, as the ‘policy that sails on wood-powered actions from civic and charitable causes to address major problems’ has clearly become unsustainable due to structural tax evasion and growing wealth inequality. The kind of intervention that comes to mind is, for instance, to reverse tax exemptions: a philanthropist who funds a private museum should be required to donate the same amount to a public cultural fund.

Thesis 3: Patronage becomes political in the distribution of certainty and uncertainty

Political analysis would fall short if we explained accelerating patronage at the expense of the treasury as an administrative mistake. Rather, it is integrally part of the European, neoliberal post-welfare state. To analyze the symbiotic relationship between neoliberalism and philanthropy in Europe, we must more closely inspect the inherent politics of patronage.

Patronage is characterized by high levels of uncertainty and elusiveness, which nevertheless harbor an attractive promise of certainty. For artists and curators, this ambiguity is directly felt. Most philanthropists only support organizations, leaving the artist dependent on an uncertain trickle-down effect. Except for a few larger funds, they apply arbitrary, hard-to-understand assessment criteria and a ‘don't call us, we’ll call you’-principle. This makes it almost impossible to build on patronage as an individual artist or curator. Yet there is always the promise, or the dream, of the gift: a successful crowdfunding campaign, a nice prize, or a fine residency, which removes a few months or even a few years of existence uncertainty.

European art institutions deal with other types of insecurity caused by patronage. Donations make up a small percentage of the total income of public institutions and broadly follow the preferences of public funds. Unlike in the case of public funds, personal honor or gain often plays a bigger role in patronage than transparency and good governance. (However, we can’t be sure how big these personal gains are. One of the key findings of the Private Museum Research project of the University of Amsterdam is: ‘While we know from anecdotal evidence that opening and operating a private museum can come with substantial tax benefits for the founder as well, the generally low degree of transparency when it comes to finances and governance has impeded us to estimate the size of these financial benefits.’) There are private museums that run (almost) entirely at a patron’s expense, but these are on average less than 15 years old and often very fragile. There can be no question of a stable public function in such volatile organizations. Yet patronage holds magical promise for institutions too: the purchase of a masterpiece, the construction of a new wing, or, increasingly, the rescue from certain demise.

Finally, the local, mostly urban community also faces uncertainty caused by patronage. Since the rise of real estate patronage, patrons have played a greater role in distributing space for arts and culture in Dutch cities. Often, real estate patrons provide a unique opportunity for a new art space. But these usually come with temporary contracts, which means the art organization quickly loses its place and can never build a sustainable relationship with the local public. Ultimately, the added value of the ‘cultured’ real estate goes to the investor, while the arts organization and the residents are the victims of the gentrification process.

So, it appears that patronage imposes an arbitrary distribution of securities on workers, on institutions, and on (urban) communities. This arbitrariness largely eludes critical analysis because gifts are supposed to be free of demands and constraints, as much as the recipient is expected to be grateful. Don’t bite the hand that feeds you… Yet it is precisely this game of distributing certainty and uncertainty on the ruins of the welfare state that is at the heart of the politics of patronage.

Thesis 4: Patronage is a function of neoliberal governance (and that’s not personal)

How does the uncertainty politics of patronage relate to public administration in the Netherlands? Remarkably, public funding for art has also become highly insecure over the past 30 years. Under the guise of professionalization, social benefits for artists (basic income-like schemes such as the BKR, WIK, and WWIK) have been abolished, work contributions for self-employed workers have been structurally reduced, and the general level of cultural funding has still not recovered from budget cuts after the 2008 financial crash. Although the national and local governments are still the biggest funder of the visual arts and the greatest hope of most artists and institutions, submitting a grant application or responding to an open call from a public art institution often feels like participating in a lottery. In this sense, patronage does not have a corrective or opposing function to public funding, but a symbiotic one. Government and patronage are the left and right hands of the same reputation economy. The ultimate example of this symbiosis is the principle of matchfunding: here, a public fund only supports a cultural initiative once it has proven itself on the market with a successful crowdfunding campaign, for instance.

The merging function of private and public funding leads to an increasingly sharp contrast in the art field: on the one hand, those who stand out in the meritocratic machinations, and on the other, the large group of less fortunate people. But however sharp, the contradiction remains porous. In the reputation economy of stock market awards, openings and media coverage, of seeing and being seen, subsistence security can be up or down at any time. Silvio Lorusso aptly summed up this situation in the slogan: ‘Everyone is an entrepreneur, no one is safe.’ Patronage functions as a magical element in this constellation, juxtaposing the apparent calculability of entrepreneurship with the hope of the intrinsic and fundamentally inexplicable commitment of gifts.

We can understand the symbiosis of different forms of public and private funding in the arts as sustaining the barely (still) governable state that characterizes neoliberalism as a whole. Philosopher Isabell Lorey writes about this in State of Insecurity: Governing the Precarious:

The counterpart of precarious is usually protection, political and social immunization against everything that is recognized as endangerment. […] However, when domination in post-Fordist societies is no longer legitimated through (social) security, and we instead experience governing through insecurity, then the precarious and the immune, insecurity and security/ protection, stand ever less in a relation of opposition and increasingly take on a graded relationship in terms of a regulated threshold of being (still) governable.

The question of whether the welfare state is still salvageable or whether we need to develop new forms of subsistence security is beyond the scope of this volume. However, I do think it is important to note that patronage as an enforcer of insecurity is an integral part of the neoliberal project. Occasional donations, as well as the hope for a magical moment of recognition, contribute to maintaining the (still) governable state of the cultural sector during the breakdown of collective security structures and the erosion of self-determination in the workplace.

A discussion on patronage can be conducted with nuance and understanding, with appreciation for generosity, and with an eye for the added value of gift culture. Yet, we will always have to face the fact that gift culture is an enabler of the deconstruction of social welfare. Or perhaps it is better to look at things the other way around: patronage is currently being held hostage as a function of neoliberalism. In typical neoliberal style, public policy is creating an ever-increasing interpenetration and thus a mutual dependency between public and private. Now that patronage has become an integral part of neoliberal governance, it can hardly function as anything other than a neoliberal tool.

This current situation is, however, not an inevitable one. After all, patronage was big before the old liberalism emerged. Can we imagine patronage beyond neoliberalism?

Thesis 5: A revolution of powerful patrons is taking place right now

Much social unrest about the role of philanthropy is caused by the revolutionary actions of a small group of large philanthropists who consider themselves above the law, tax liability, and democratic processes. The ideology put forth by these power-hungry patrons is voiced by their puppets like Wim Pijbes, the director of the philanthropic fund Droom & Daad. Pijbes has advocated for less regulation and more reliance on big money to guard (national) culture and its standards of quality. They are no longer interested in matching government decisions and reject 'imposed politically correct interpretation,’ in the words of Pijbes. They want to return to ‘art as art is meant to be.’ And they seize the initiative. By founding private museums or taking control of public institutions, they develop the urban environment single-handedly and shape the ‘Collection Netherlands’ as they see fit.

In The ABC of the Projectariat, Kuba Szreder diagnosed such toxic philanthropy 'as blatant manifestations of the will to power, in […] neoliberal guise'. However, I think the situation is even worse. The discourse of the power-hungry patron is neo-illiberal: an appeal to classical-liberal values from an elitist-autocratic and chauvinistic slant, with great distrust of the democratic control mechanisms of the liberal state. These patrons are ridding themselves of the burden, imposed by neoliberal governments more than any other, that public art exhibitions should rely on private support. The revolution of the powerful patron is therefore, in fact, a liberation of patronage from the grip of neoliberalism. (Publicly, most power-hungry patrons adhere to public values like diversity and inclusion. We should clearly understand this stance as an expression of populism and marketing rather than public accountability.) Yet it is quite likely that the philanthropic initiative will enter the publicly funded part of the visual arts sector through the back door and start competing for already scarce public resources. In this competition, the philanthropic initiative would have the advantage of private base funding. In an extreme but certainly conceivable scenario, the power-hungry patrons will take the lead in cultural policy, and it will be the government who will be fund-matching them.

In the process of the neo-illiberal revolution of power-hungry patrons, the social dialogue between traditional workers’ and employers’ representative organizations is entirely sidelined. The government's interlocutors in determining policy, such as trade unions, collectives, committees, and professional and industry associations, have no place at the table of the power-hungry patron. There can be no misunderstanding here: no powerful patron seeks union approval. The individual actions of the powerful patron thus undermine public control as well as workers’ emancipation. This is undeniably a liberation of patronage – in a disastrous direction.

Thesis 6: A democratic liberation of patronage is possible

What response does the artist propose in the face of the revolution of the power-hungry patron? It is urgent to quickly, publicly, and concretely explore more democratic possibilities for a culture of giving beyond neoliberalism. Not only are ethical principles and political visions important here, but tactical interventions as well.

Precarity reigns in the cultural sector and patronage, whatever one may think of it, is currently an important funding stream. Helleke van den Braber therefore argues that artists should be able to think carefully about the kind of relationship they want to enter with patrons, actively formulate a funding request, and set their boundaries. More concretely, Renée Steenbergen calls for precarious workers to have more direct access to philanthropic money. Practical inferences from these reflections range from opening funding schemes for individual art workers to making the funding criteria for philanthropic funds more transparent and offering artists courses in negotiating. These small improvements may seem like opportunistic quick fixes, but they will make real changes in the real lives of real art workers.

It is also important to remember that tactical interventions are more than band-aids on a broken system. They provide opportunities to speculate, imagine, and prefigure new forms of organizing. For instance, Berlin-based gift circle Circles uses blockchain technology to self-organize a basic income for cultural workers. Het Actiefonds, which connects small-time patrons to global actions for social justice, creates a bridge of solidarity. Thus, tactical action can result in new forms of giving – decentralized, collective, anonymous, communal, and solidary – which in turn provide a testing ground for new ethical principles and political visions. For instance, after decades of working with the Arts Collaboratory and experimenting with trust-based funding, Stichting DOEN has formulated leading questions for 'a funding paradigm shift', which I believe is a very healthy discussion to have.8How can we develop a funding practice that operates in this living system, enhancing sustainability of ecosystems, instead of repeating (post-)colonial practices and imposing Western paradigms? What does a funding practice based on mutual support, solidarity, local relevance and openness really mean? How can we redefine ‘sustainability’? Less focussed on (financial) sustainability of individual organisations and more on creating so called ‘living’ ecosystems, in which both organisations and funders operate in a dynamic, larger ecosystem, and in which there is a more holistic approach combining cultural and ecological values. How can we redefine and decentralise the role of money in our practice, and give more intention and emphasis to other values such as knowledge, collaboration and solidarity? How can we practice with collective ways or collaborations to enhance our organisation processes? What are the practical mechanisms and tools we can build as alternatives to accountability?

Despite my concerns about the neoliberal function of patronage and the revolution of the power-hungry patron, I am convinced that a bottom-up, organized, democratic liberation of patronage is possible. If patronage becomes political in the distribution of certainty and insecurity, great freedom reveals itself in this: the fundamental non-regency of generosity. Let this non-reducibility become a basis for a culture of giving in solidarity that cultural workers shape together.

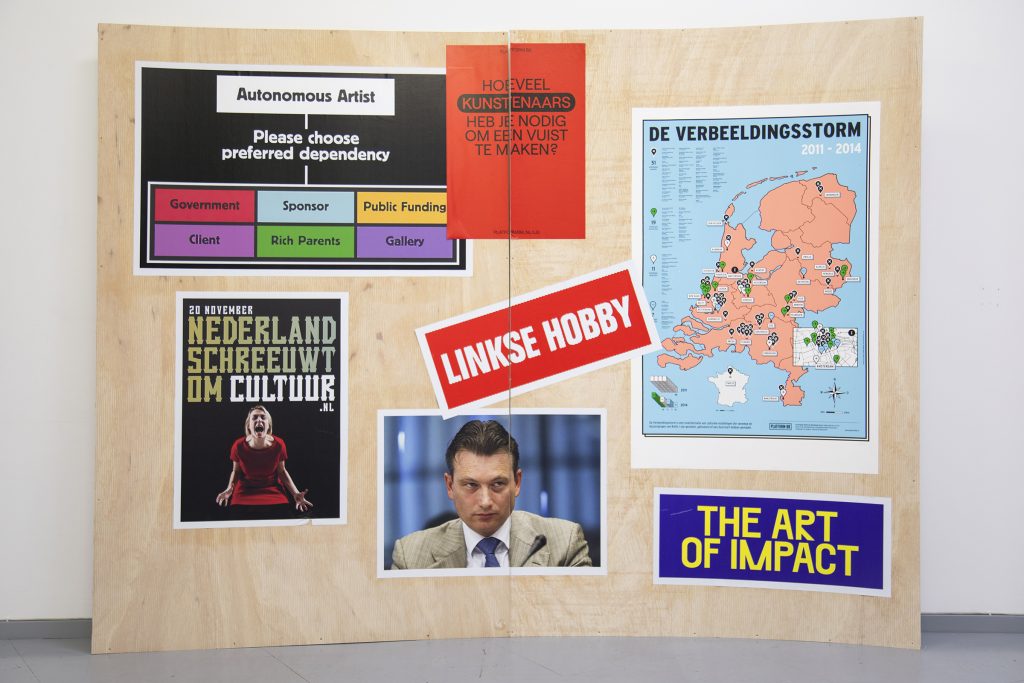

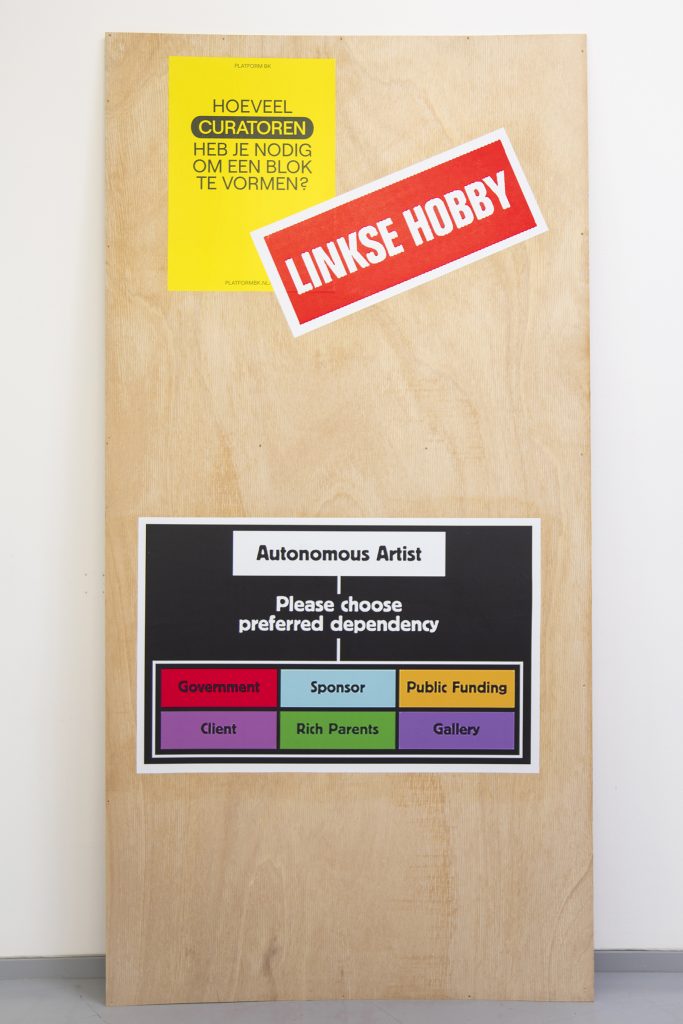

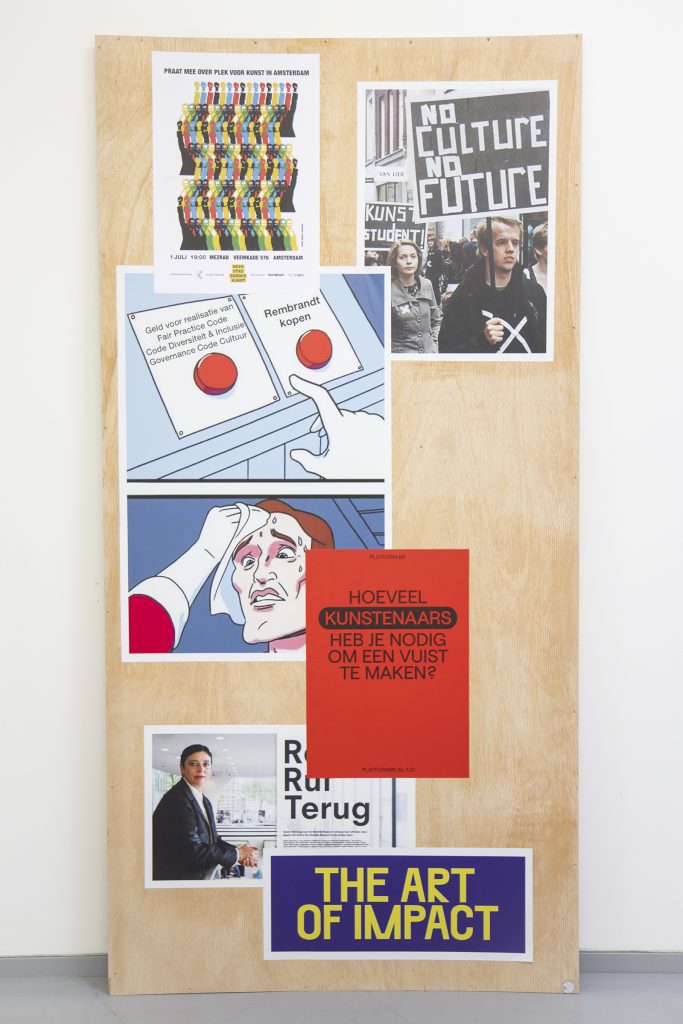

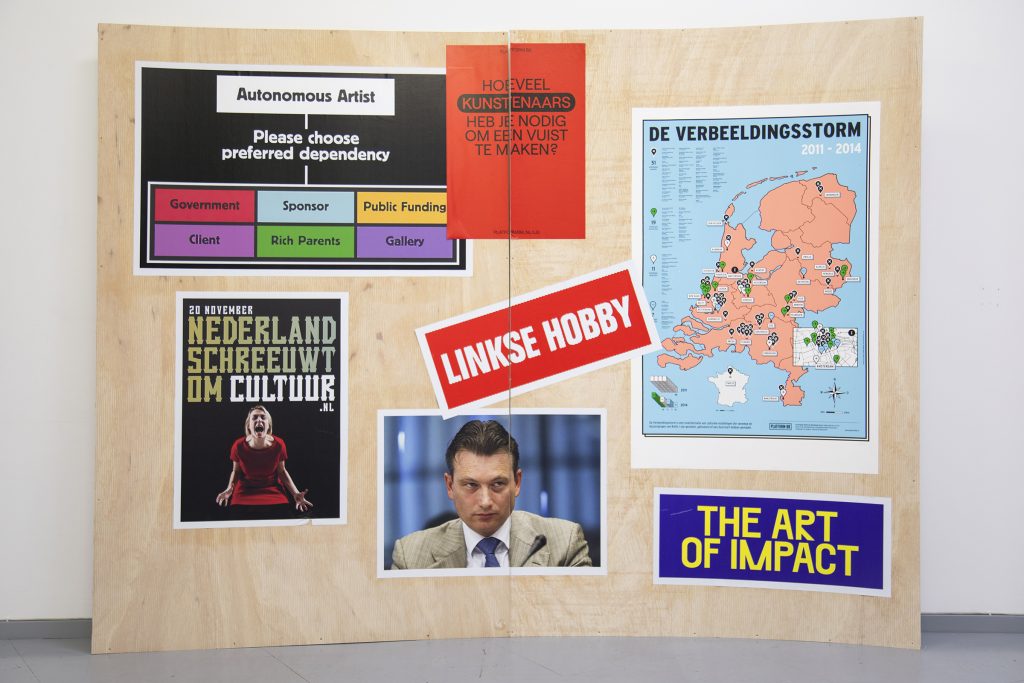

This text was authored by Sepp Eckenhaussen, an arts researcher at the Institute of Network Cultures (Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences) and Caradt (St. Joost Academy of Art & Design), and previous co-director of Platform BK (2020-2023). Candela Cubria supported and proofread the translation. Editorial feedback by Jeannette Slütter. The wooden panels in the pictures were made by Timo Demollin, with input from the members of Platform BK, and served as the decor of the symposium De Staat van Mecenaat.

Cover image: 'Tutto: Ordine e Disordine' (2018) by Matilde Cassani, at Manifesta 12 in Palermo.