In this session, contributors Joke Hermes, Marijke Hoogenboom and Ela Kagel each presented their unique perspectives the creative industries. Coming from positions in and outside of academia, the overarching theme they each acknowledged was a question of space for creative practitioners to work. This pondering of how structured organisations effect conditions and perspectives on creative production was also deeply concerned with the ability of those within and without the industry that were able to support themselves financially. One question during the discussion demonstrated this quite fittingly, enquiring how many people in the audience were being paid as they were attending the conference. In this blog post I shall briefly summarise the arguments from each speaker.

Joke Hermes

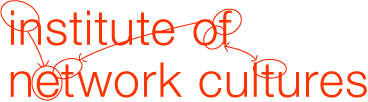

Hermes focussed on the mythologised status of individual professionals within the creative industries, and the different labels used when describing these creative workers. Hermes was primarily interested in freelancers, or “independent professionals,” which are typically thought of in one of two ways.

The first is the Free Radical. Hermes cited Dutch entrepreneurs Alexander Klöpping and Daan Roosegaarde as embodying this label: good at acquiring project funding, and sitting on the edge between artistry and entrepreneurship, she described them as “idealist engineers for a better world.”

The first is the Free Radical. Hermes cited Dutch entrepreneurs Alexander Klöpping and Daan Roosegaarde as embodying this label: good at acquiring project funding, and sitting on the edge between artistry and entrepreneurship, she described them as “idealist engineers for a better world.”

The second image is the Precariat. A relatively new concept, members of this group are victims of the global economic crisis and practices such as the outsourcing of work. This means that people who would otherwise aim to have full time jobs are required to work sporadically and/or from home in order to make ends meet.

Referencing her quantitative research interviewing members of the independent creative community, Hermes drew our attention to at least two additional identity formations that should be recognised. The third image is the Artist. Working in editing, publishing, graphic design, PR and so on, these creative independents identify as artists, rather than as what is dictated by their job label. Hermes didn’t offer a definitive term for her fourth image, simply noting that it was based not in creativity per se but rather in a desire in people to be able to work to live, to provide both for themselves and be able to care for others around them.

Hermes noted that she has seen a move from perceptions of artistic genius, back towards a more old-fashioned notions of vocation and the artisan’s guild. She argued that the problems within the current logics of policy making and state regulation of the creative industries could be countered with a return to the guild system. She cited the culture of unpaid interns as being a negative symptom of the current system, which could be adapted into a reformulated guild as a means of providing real experience and unionised support for a currently subjugated group within the creative industries.

Concluding her discussion, Hermes denounced the current trend of neoliberal romanticism, and cited the guild as one of the possible ways to improve the creative industries in the future.

Marijke Hoogenboom

Marijke Hoogenboom

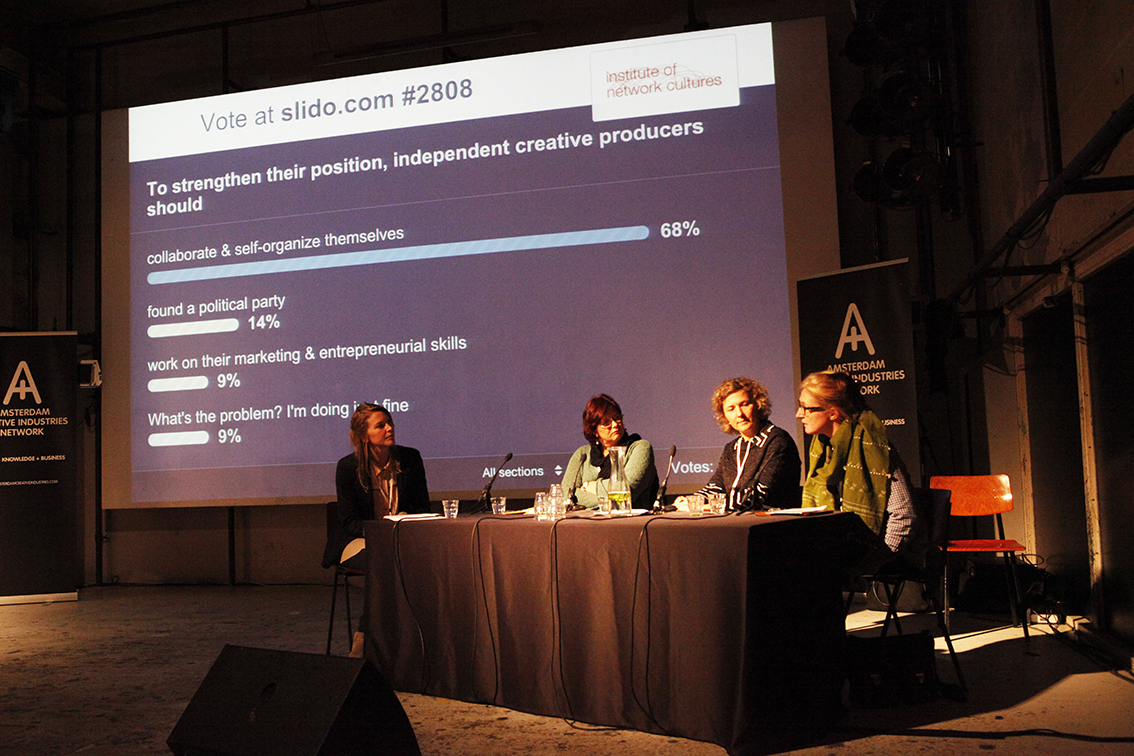

Hoogenboom’s experience with cultural policy and artist collaboration led her in this talk to consider the creative production not after, but before the industry, in order to better understand what is at stake now.

Hoogenboom confidently stated that theatre used to be characterised by its unproductively; that is, that it requires a great deal of time, labour and resources to be invested in rehearsal, with no guarantee that the process will be successful. Moreover, theatre itself is intrinsically ephemeral, existing only at the time that it is performed. As the performing arts in the Netherlands is becoming increasingly reliant on public money, they need to legitimise themselves; this means leaving a lasting impact or commodity, a requirement which goes against the nature of theatrical practice.

She highlighted a crucial problem with arts funding within the Netherlands as being concerned primarily with supply and demand, leading grant allocation to be dependent on the promises of larger audience reach, rather than the potential quality of what is to be produced. As stated by Hoogenboom: “There simply is no demand; let there be supply”.

Hoogenboom lamented the loss of sustainable conditions for the slow productions of theatre, noting that the lack of these conditions leads to the decline of complex and experimental practices. The effect of conditions on practices should not be trifled at; Hoogenboom noted that practitioners are “systematically discouraged” to engage in proper research, idea development or even time for reflection: they do not result in tangible output, and are therefore not paid for.

Further, Hoogenboom critiqued the emphasis on justifying the quality of art programmes within higher education as based upon the employability of graduates, arguing that art education should not have to reflect market needs.

She finally highlighted a growing sense of community collaboration and radical sprit in young creatives as offering hope to the future face of the performing arts. More concretely, Hoogenboom acknowledged her own position as an influential member of the academic community. Hoogenboom announced that she was in talks to create a “local school” as part of the new Amsterdam Theatre School campus at Groot Lab in Amsterdam Noord, not as a formal means for education, but to question what it means to work and educate artists, and also what it means to be a part of urban renewal and shifting regimes of space.

Ela Kagel

Ela Kagel

Creative industries, particularly in Berlin, are fundamental for cities to sell themselves internationally. Additionally, the creative industries have become very much associated with the start up scene, to the point where discrete elements of each have become conflated: “culture, the arts, the creative industry and the start ups… merged into one huge realm of market opportunities.”

Kagel tackled the question head on: what does it mean to be a creative practitioner in this day and age, and how can these creatives organise themselves? She points to open, unregulated community spaces as being prime assets for a city. Further, and drawing on Hermes’ arguments, the heterogeneity of creatives should be emphasised and community diversity embraced in order to properly function outside of state and market controlled structures.

Coworking spaces encourage those within them to learn from one another, gaining habits and skills that Kagel argues cannot be taught through formal training or in education. Coworking spaces encourage creation of new cultural practices, social innovation and politicisation; they offer small communities with their own rules to develop, from which elements can be taken up and implemented on a societal level.

Kagel emphasises the importance of these coworking spaces to collect data on those inhabiting such environments. This collection would allow them proper political representation that has not been possible thus far.

Within her own hybrid community space, SUPERMARKT in Berlin, Kagel has identified the importance of creating an environment of social support and exchange, of working with outside forces such as city administration as a means of increasing visibility but also of maintaining control from below rather than above. She believes that taking the steps mentioned throughout her talk are crucial to keep these vital community spaces alive.