Despite the fact that you might disagree with his idea on happiness, the following statement by internet artist Rafaël Rozendaal illustrates how he feels about defining internet art, as well as the struggle on terminology in today’s art world. Over the last few years there has been an increasingly popular and inspiring discourse related to the ubiquitous of digital technologies and the internet. Whether we call it new media art, internet art, digital art, post-internet art or post-digital art, there are some interesting artists, ideas and critiques to discover. In case you missed it, No Internet, No Art let’s you catch up.

“Cultural categories can be helpful to discover things, but we shouldn’t take them too seriously.

Art can’t be defined. Try it. It can’t be done. We all kind of know what it is but no one really knows. No one really knows what happiness is either. The moment you know it, you’re not really happy. When you’re really happy, you’re not thinking about happiness.

The internet can’t be defined either. It’s part of our subconscious and dreams and daily lives and relationships and business and family and identity… it’s… everything.” – Rafaël Rozendaal

No Internet, No Art, A Lunch Bytes Anthology is both the documentation of and commentary on a series of events, which took place between 2011 and 2012 in Washington, D.C. that examined art and digital culture by addressing the role of the internet in artistic practice from a wide range of perspectives. This series consisted of ten events with themes like ‘Copy Culture’, ‘Surveillance, Security and the Net’, and ‘A New Aesthetic? – Beyond Lunch Bytes II’. For a complete overview of the events and their themes, check the Lunch Bytes website. In general, each discussion involved two artists and two experts, invited to present their work, and reflect on the topic. Since the first series weren’t recorded, this book let’s you catch up on the debate.

Melanie Bühler, founder of Lunch Bytes and editor of No Internet, No Art, contextualises the concept and origin of Lunch Bytes as closely linked to a discourse that emerged around 2010. She refers to the exhibition in the New Museums The Generational Triennial: Younger Than Jesus, in which the artists moved ‘seamlessly across media’ according to curator Lauren Cornell. According to Bühler, “The curators didn’t speak of the digital as a separate medium, they framed it as a cultural condition that could be addressed through all kinds of media.” She also refers to the essay The Image Object Post-Internet by artist Artie Vierkant. “Vierkant introduced this term to describe a specific kind of contemporary artistic production that deals with the internet and digital technology, yet focuses neither exclusively on its technological subgrade nor solely on the dissemination of an art work.” In this essay Vierkant indicated the implicit tension between new media and post-internet, which triggered Melanie Bühler to come up with the concept for Lunch Bytes.

“I’m not sure what the exact definition is, but I keep hearing the term “Post internet art”

It usually refers to artists who are “internet aware” and then make art inspired by their world wide web impressions.” – Rafaël Rozendaal

According to Bühler the most obvious development in the field since the start of Lunch Bytes, is that post-internet art has become fashionable. In 2014 post-internet was discovered as a marketable label. Not only does the service ArtRank – a platform that gives you an unprecedented data-driven advantage in art collecting – mirror the influence of digitization, it ranked (and still ranks) Artie Vierkant as top artist to be bought under $ 30,000. In addition, the number of panel discussions, exhibitions, articles and publications related to post-internet art started to grow.

Because of its power and limitations at the same time, Bühler intentionally never used the term post-internet art during the Lunch Bytes sessions. The term seemed to hijack the conversation because of the discussion on terminology, while she was more concerned with broadening the scope than defining a new movement in art history. In this publication, the struggle on terminology is clearly noticeable. Different genealogies, perspectives, and terminologies (net.art, new media art, internet art, digital art, post-internet art, new aesthetics, and post-digital art) are juxtaposed and therefore highlight what Bühler calls a “problem space”.

“Using the term “new media art” leaves us with the sour aftertaste of something that has fallen out of fashion. Internet art sounds cute, but also somehow rusty. The chapter of net.art appears to have been closed. Finally – at least for now – post-internet has turned into a catchphrase that has been discussed so many times that it has started to bore people.” – Melanie Bühler

Just like the Lunch Bytes sessions, which want to address digital culture from a wide range of perspectives, the book covers an overwhelming amount of different topics and perspectives from the field of art history, media studies, philosophy, curatorial studies, and design. The book consists of contributions, mainly essays and interviews, which were directly derived from presentations during the first Lunch Bytes sessions. In addition to these contributions, No Internet, No Art includes fourteen commentaries, in the form of interviews, with experts that reflect on the contributions and aim to contextualize important concepts and key statements. Bühler conducted these interviews in 2014, a good way to actualize the content again. The dynamic concept of the book pays homage to the internet. Contributions are alternated with commentaries, and the images are disconnected from the related texts, shuffled around and assembled according to a digital aesthetic logic.

While most of the contributions are related to artistic production and changing models and modes of working, some of them deal with topics beyond the realm of art. These focus on the influence of digital technologies and cultural changes such as the digitization of labour, social media issues, archiving, the culture of sharing, activism, politics, preservation, querying, and surveillance. Other contributions by artists Jon Rafman, Mark Tribe and Natalie Bookchin focus on specific artworks and zoom in on their individual art practices. Another category has a curatorial perspective and focuses on the challenges and specificities of dealing with and exhibiting internet-related art. Among the interviews, artists Aram Bartholl, Michael Bell-Smith, Joel Holmberg, and UBERMORGEN address how they engage with digital culture. There are also two contributions that differ from the other ones: an interview by Rafaël Rozendaal, who interviews himself about his practice (the cited blog post about the definition of an internet artist is partly included), and a poem by Adam Cruces and Pierre Lumineau (to which the book owes its name). Finally, a couple of essays by Daniel Pinkas, Katja Kwastek and David M. Berry are dedicated to The New Aesthetic. The wide range of perspectives makes No Internet, No Art a good starting point to catch up with the debate and select topics of interest for further reading.

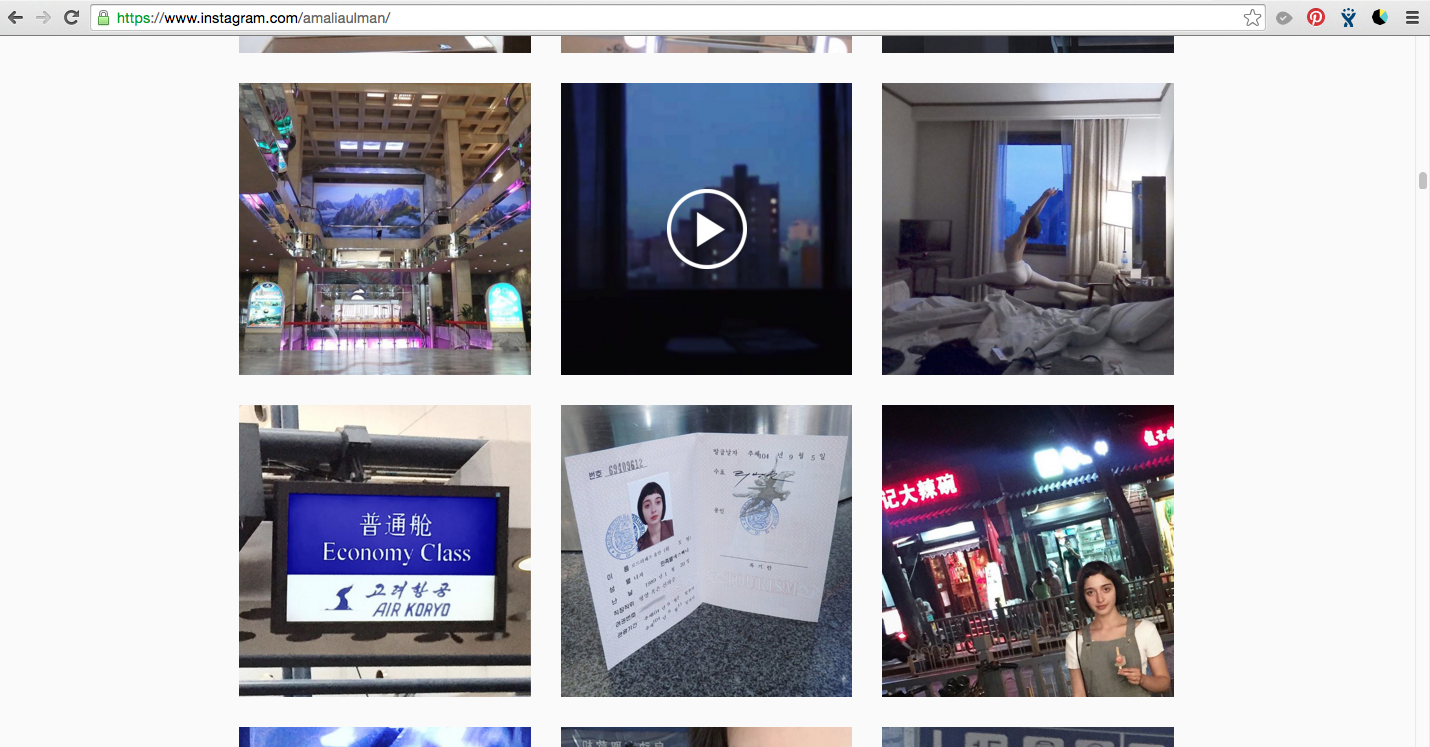

Because the digital has become a concept too vague to function as an overarching theme, we should instead focus on circulation, performance, and abstraction, states Bühler. These three interconnected phenomena are crucial to our understanding of digital culture in its present state, and feature as vital concerns in the work of contemporary artists. Firstly, she refers to the work of Martijn Hendriks, in which the accelerated exchange and circulation of physical and informational objects facilitated by network technologies, becomes visible. Secondly, Amalie Ulman, who reflects in her work on the state of constant performance, online self-promotion and the concept of branded lifestyle induced by social media networks. Ulman stages her online presence in a distinctly erotic manner and produces art works that are part of a simultaneously seductive and enigmatic performance. Thirdly, the notion of abstraction, as a result of a complex and multi-layered technological and economic infrastructure running in the background, is of interest in the work of Harm van den Dorpel. He has developed an algorithm that creates new connections between the images he has produced. This algorithm plays an active role in creating new art works because it decides which images should be brought together and turned into future works. In this way, the abstract, programmed structure materialises in his art works.

“… the only prediction that I would dare make regarding “the future of art” is that the notion of art, what it is, and what it can do, will continue to change, and that the tension between progressive, conservative and lateral movements, between avant-gardists, rear-gardists and transversalists will continue to constitute and confuse that obscure practice and object of desire that we call art.” – Andreas Broekmann

These three phenomena will be explored further in future Lunch Bytes events. Will we still be talking about post-internet art? No one knows but there’s a great chance we will have embraced another catchphrase.

No Internet, No Art, A Lunch Bytes Anthology

Edited by Melanie Bühler, published by Onomatopee.

- Martijn Hendriks – Installation View Searching For Devices Basis Frankfurt, 2015. Image: http://www.martijnhendriks.com/

- Screenshot Instagram Amalia Ulman. https://www.instagram.com/amaliaulman/

- Harm van den Dorpel – Deli Near Info. Screenshot http://delinear.info/

References

ArtRank: http://artrank.com/index.php

How could you define an “#internet #artist”?, blog post by Rafaël Rozendaal (no date), http://www.newrafael.com/how-could-you-define-an-internet-artist/

Keiu Krikmann interviews Melanie Bühler/ Lunch Bytes, March 2015, http://www.ofluxo.net/keiu-krikmann-interviews-melanie-s-lunch-bytes/

Post internet art, blog post by Rafaël Rozendaal (no date), http://www.newrafael.com/post-internet-art/