STRIPTHƎSIS2023.004 It is the difference that will not go away, the difference between what others see of us and our sense of our inner selves and the deep feelings that sustain it. — Julian Jaynes

How would you know if you had died? Short answer: you wouldn’t. You would, sure enough, know if that were to happen to others, but you can only presume what others would know about you, right after you were no more. As you cease to exist, the act of knowing will no longer be your province.1 Nor will the fact of being. As many as there may be, provinces won’t have a place to settle. For some awareness to exist, there must be a subject from which this awareness derives. Which begs a follow-up question: if you did die, how would you know, then, not to keep being? What would make you aware of the fact that you no longer belong to the domain of the living? We know you wouldn’t be anymore, but who would tell you this, so that you could stop realizing, interpreting, investing, or intending? And how would they tell you this, even if they wanted to, if there is no you to tell it to? We arrived very quickly at the central problem of the limits of consciousness that, for years, has been salting my waters.

As far as you are concerned, the world exists merely as a representation, an idea retrieved and reproduced to its limit with the help of billions of tiny little demons,2 inhabiting your cognitive surroundings. To this, you could call reality. The coffee you usually enjoy or despise, this music you have stuck inside your head, or the one you can’t remember, that thought you just had about something you’re supposed to do later, and some memory you just recalled, for no specific reason, and forgot moments after – these are all slices from this block of knowing you feel engulfed in. You can’t quite put your finger in it, but it’s around you, in you, and it’s you. You can’t remember when it started, and you’re unable to know why, or where it’s going.

But the definition of consciousness, as it were, doesn’t merely reside in its property of being aware of itself through a channel enacted by a conscious being who is, by definition, aware of themselves. Even though it holds this particular notion, to try and define the specifics in this matter of consciousness is going to take much more sweat and tears than those exerted from recognizing it as a mere POV which, accidentally or not, shares the same hollow server (the known universe) with an infinite number of other participants, each with their point of view. Perhaps the problem of the origin of consciousness can be resolved by identifying the brain regions responsible for consciousness and then tracing their anatomical evolution. Additionally, if we examine how current species behave in relation to different stages in the development of these neurological structures, we will finally be able to define consciousness experimentally. At least scientifically, so to speak.

Let’s pursue this a little further, with a colourful example. What if, say, Tommy Vercetti suddenly became aware of himself, at the exact moment he was fleeing from the Haitians in the vicinity of Little Havana? Would he complete the mission, so essential for his life (or so we’re led to believe)? Or would it impede him to proceed, remaining stuck in a state of self-analysis that would inevitably – if he weren’t to be shot in that process, of course – end with someone in your room, perhaps even yourself, having to get up and reset the game console? And if that were to occur, what effect would that have in now-conscious-of-himself Tommy? Would that action reset, as well, his newly acquired power of being here and now? Now imagine yourself as Tommy, imagine the Haitians as some big trouble you are facing in your life right now, and try and think if you’re actually in control of your fate. Attempt to locate your motivations. Try and remember why you are, indeed, trying to finish this mission. Try and remember who you are, and do this concerning both yourself and your known universe.

Now, what in the hell did you do to these Haitians to make them hate you so much, to the point where you have to run around, fleeing for your life? Was it intentional? Did you mean to betray them? Or were you being led by a higher power, an outside controller, which made you do things without you being aware? No, that can’t be. You’re completely aware, you’re here! You’re here, and you’re there, and you know yourself, and you know the world you inhabit, through yourself nonetheless, but you know it: it’s this reality. No question can be made about intention, at least not generally, as every choice you made was conscious, even if not conscientious, right? What is even the point of asking these questions, if their recipient is you? You can’t know about yourself more than what you’re allowed to know. The tools you have that permit you to analyze, and eventually comprehend reality, are attained with whatever licenses the known universe has granted you access.(Fig. 3) Therefore, any answer you might come up with is already compromised by default. Tommy Vercetti cannot comprehend he’s the main character in a popular video game any more than you can comprehend any particularity about an unknown universe, whose existence you’re not capable of proving, and of which your known universe may or may not be part.

Fig. 3 — Max Planck, 1931

‘In driving a car, I am not sitting like a back-seat driver directing myself, but rather find myself committed and engaged with little consciousness. In fact, my consciousness will usually be involved in something else, in a conversation with you if you happen to be my passenger, or in thinking about the origin of consciousness perhaps. My hand, foot, and head behaviour, however, are almost in a different world. In touching something, I am touched; in turning my head, the world turns to me; in seeing, I am related to a world I immediately obey in the sense of driving on the road and not on the sidewalk. And I am not conscious of any of this. And certainly not logical about it. I am caught up, unconsciously enthralled, if you will, in a total interacting reciprocity of stimulation that may be constantly threatening or comforting, appealing or repelling, responding to the changes in traffic and particular aspects of it with trepidation or confidence, trust or distrust, while my consciousness is still off on other topics.’ 3

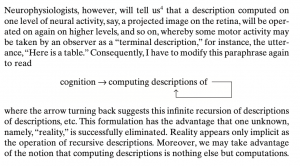

As Julian Jaynes suggests, if we might find ourselves unconsciously enthralled in this simulation of reciprocity stimulation, we could consider ourselves a victim of consciousness. Not only wouldn’t we be able to perform in this manner – automatically deviating from traffic, gear up and gear down, mirrors and levers, and all the mechanical behaviours proper of the complex task of driving a car – if we weren’t continuously possessed by this bathing autonomous virtual mass of reality-awareness, as it would also be impossible for us to operate subconsciously without the precious aid of those aforementioned demons, helpers of undefined quality, pulling strings and dropping bags of sand so that we may reach the doctor’s office, or a date with our loved one, safely and timely. To simplify this idea, if you find yourself deep within your conception of what is, then you’re inevitably part of this conception, which is part of your conception, which is part of this conception, and so on, in an infinite recursion of descriptions of descriptions of descriptions (Fig. 4). There is no possible end to something which had no beginning, or vice versa, it could be said, even though that would certainly be a heavy statement, which is why I won’t say it. I will merely write it. And from here on out, we shall continue, to find out how deep the rabbit hole goes.

Fig. 4 — Heinz von Foerster, 2007

Looking at what Hume thinks about how we might interpret matter within our conscious being, through the vision of H. H. Price Wykham, we understand that the conclusion which Hume draws is, to all appearances, purely destructive. According to him, ‘our reason and our senses are in direct and total opposition; or, more precisely, between those conclusions we form from cause and effect (in our study of the physiology of the sense-organs) and those that persuade us of the continuance of body. The ‘unsensed sensibilia’ postulated by the Vulgar — the unseen colour-expanses, the unseen pressures, the unseen sounds, which are supposed to fill the gaps in our fragmented and interrupted sense experience — do not in fact exist. This is as certain as anything in science can be. We all continue to believe that they exist, even though they are demonstrably false, and despite philosophers’ best efforts, their proposed replacement is utterly illogical and not even false, proving that they are actually constantly holding to the original fallacy.’4

What’s the matter, then? Did you see what I just did there? You did, even if you didn’t understand what I just said, or why I said it, because of that device you have installed in your brain, constantly gap-lining every moment, making it seem it’s all just one continuous experience. That device makes you believe there is a past, and a subsequential future. But what about the present? What about what is presently occurring? Wouldn’t that be everything? The ever-continuing experience itself? The whole knowable universe, all of the matter, has to be part of this present, this ever-flowing faucet of reality, seemingly flowing from the past, which is what happened (constantly archiving itself beyond your will), to the future, which is what will happen (the arbitrary sum of what’s expected and what’s unexpected).

On top of this mirror’s edge game, there is another interesting side phenomenon: the archiving of future events as memories. This would be everything you’re setting out to do, and everything that’s set out to happen to you, pertaining to both the realms of awareness and unawareness, being neatly compiled already as expectations, both from the expected and unexpected situations which will, or won’t unfold within the physical reality you keep perceiving as real. In the middle of this ‘temporal storm’ 5, you exist, almost unwarrantedly, if one would procure to define it under a poetic gist. You’re grounded to your space through time, and vice versa, therefore grounded to yourself through your Environment.6 Thereupon, the following question arises: is it your Environment you’re living in? What makes that Environment yours? Can you prove that to anyone besides yourself? You would think the fact that you are the one experiencing it should be enough to comply with this silly request. Notwithstanding that everyone else is experiencing some Environment simultaneously, as you may be able to conclude from your empirical observation, those other environments couldn’t be the one you’re referring to. Yours comes from you, it has this invisible watermark that angrily shouts ‘My interpretation, all right!?’, in the voice of George Costanza – why not? – thus never being mistaken for a different one! It’s perceived by you, so its origin is easy to trace, for without you there would be no such context.

Heinz von Foerster, 2007

The trouble continues when we understand that this so-called environment — the hollow server every living being has been granted access to — may be split into billions, trillions, perhaps even a perpetual bundle of versions that take place at the same time, piling up like Friday evening city traffic. Some have been lasting forever, and some have commenced showcasing this very moment. But since this very moment is unable to be located, being impossible to freeze, probably, this splitting arrangement is also part of the illusion. A fictitious humane-friendly representation that serves the sole purpose of helping us to better understand the intricate concept of existing collectively in a potentially infinite amount of individual simultaneous universes. This inconceivable reality is constantly being observed, thus constantly reacting to it. To the old question ‘If a tree falls in a forest, and there’s no one around to hear it, does it make a sound?’ I will counter with ‘If a tree falls in a forest, and there’s no one around to see the forest, is there really a tree, and a forest?’

Not by any stretch of the imagination is this question an original quest, at least not in its philosophical basis. However, where the field of Quantum Mechanics is concerned, a similar experiment has been made, and the results are surprising.7 If the act of observing an object has a definite influence on the manner of how this object will behave, then we may, at the very least, surmise that reality, as we know it, deeply relies on the presence of conscious spectators to unfold the way it does, if not to unfold at all. Being so dependent on its viewers and admirers, this reality of matter could even become so unconsciously enthralled that it might, within the limits of possibility, forget to put a stop to keep being observed.

That it is, we all know this. That it can be, simultaneously to different agents, is also apparent, even if not certain. But can it cease to be, altogether? Is this really that heavy of a statement, too heavy to be said? Just light enough to be written, perhaps. Just imagine a forest that has been here, there, and everywhere, forever lasting, wherein you can’t recede nor proceed, standing still in what, to you, seems like a constant ever-flowing state of presentness. It’s the perfect clash between the very bottom of the dryest canyon and the absolute surface of the most turbulent ocean. Like a cocktail of emotional splattering, combined with rational stuttering, a dot of wandering wondering, a dash of wavering weaving, and a lot of tree-falling observing, all of this being broadcasted to-and-by an endless quantity of interpreters with views that keep deriving and deviating from an even more unfathomable number of angles. What if, upon arriving, you parked your car by the entrance of this forest, and there was no one around to see you do it — did you really park it? Are you really there?

—

Notes:

1 Scarre, G. (2014). Death. Routledge. p 2. — “But here, as Epicureans point out, there is a puzzle. For while it is natural to speak of my death as depriving me of actual and potential sources of satisfaction, to anyone who believes that death is the extinction of the self, there is henceforth no me to suffer any loss. Death is the end not only of the play but of the actor.”

2 Von Foerster, H. (2007). Understanding Understanding: Essays on Cybernetics and Cognition. Springer Science & Business Media. p 103. — “Unfortunately, there is one crucial flaw in this analogy inasmuch as these systems store books, tapes, micro-fiches or other forms of documents, because, of course, they can’t store “information”. And it is again these books, tapes, micro-fiches or other documents that are retrieved which only when looked upon by a human mind, may yield the desired “information”. By confusing vehicles for potential information with information, one puts the problem of cognition nicely into one’s blind spot of intellectual vision, and the problem conveniently disappears. If indeed the brain were seriously compared with one of these document storage and retrieval systems, dis- tinct from these only by its quantity of storage rather than by the quality of the process, such theory would require a little demon, bestowed with cognitive powers, who zooms through this huge storage system in order to extract the necessary information for the owner of this brain to be a viable organism.”

3 Jaynes, J. (2000). The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p 2.

4 Price Wykham, H. H. (1940). Hume’s Theory of the External World (1st ed.) [Reprinted photographically in Great Britain, in 1948 from sheets of the first edition]. Oxford University Press, Amen House, London E. C. 4. pp 101-104. — ‘Thus our ordinary vulgar consciousness of matter consists, according to Hume, of two sharply distinguishable elements: the sensing of gap-indifferent and succession-indifferent sets of sense-impressions; the imaginative postulation of unsensed sensibilia to fill up the gaps.’

5 From the Portuguese language, the word ‘temporal’, aside from being related to time (PT: tempo), can also be used to describe a severe storm, characterized by the presence of strong winds, heavy rain, and even thunder. Thus, the expression temporal storm here is to be taken as a tender play with words, through a cross-idiom hyperbolic pleonasm.

6 Von Forster, 2007, p. 211 — ‘I am sure you remember the plain citizen Jourdain in Molière’s Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme who, nouveau riche, travels in the sophisticated circles of the French aristocracy and who is eager to learn. On one occasion his new friends speak about poetry and prose, and Jourdain discovers to his amazement and great delight that whenever he speaks, he speaks prose. He is overwhelmed by this discovery: “I am speaking Prose! I have always spoken Prose! I have spoken Prose throughout my whole life!” A similar discovery has been made not so long ago, but it was neither of poetry nor of prose — it was the environment that was discovered. I remember when, perhaps ten or fifteen years ago, some of my American friends came running to me with the delight and amazement of having just made a great discovery: “I am living in an Environment! I have always lived in an Environment! I have lived in an Environment throughout my whole life!” However, neither M. Jourdain nor my friends have as yet made another discovery, and that is when M. Jourdain speaks, may it be prose or poetry, it is he who invents it, and, likewise, when we perceive our environment, it is we who invent it.’

7 ‘When a quantum ‘observer’ is watching, Quantum Mechanics states that particles can also behave as waves. This can be true for electrons at the sub-micron level, i.e., at distances measuring less than one micron, or one-thousandth of a millimetre. When behaving as waves, electrons can simultaneously pass through several openings in a barrier and then meet again on the other side. This meeting is known as interference. Now, the most absurd thing about this phenomenon is that it can only occur when no one is observing it. Once an observer begins to watch the particles going through the opening, the obtained image changes dramatically: if a particle can be seen going through one opening, it is clear that it did not go through another opening. In other words, when under observation, electrons are more or less being forced to behave like particles instead of waves. Thus, the mere act of observation affects the experimental findings.’ — Venkatesh Vaidyanathan

—

More about the author here.