Maxim Kondratiev is a coordinator of Avtozak LIVE, an independent media that covers protests and the violations of rights in Russia. Avtozak LIVE is mostly active on Telegram, where their channel has almost 51.000 followers. We talked with Maxim in early May via Zoom. He is currently residing in a migration centre in the Netherlands, where he applied for political asylum after the war had broken out. In the following interview, he talks about the current state of the Russian protests and explains how the surveillance system helps the Moscow police to detain people.

How does Avtozak LIVE operate within the realities of war? Were there any radical changes in what Avtozak LIVE publishes or how the journalists communicate?

Maxim Kondratiev: Over the past two months, our entire editorial staff has been in a state of shock, and only now the sober reflection on the war, our country initiated, has begun. There hasn’t been any fundamental change in the way we work, and none of our journalists or coordinators has quit. The only radical thing that has happened is that Avtozak LIVE now, like many other Russian media, can be called international. Our employees do not exclusively live in Russia anymore, but also in Turkey, Armenia, Georgia, or, like me, the Netherlands. Still, most of the editorial staff remain in Russia. Even those who remained in the country work quite openly. In any case, at the rallies of recent years, almost all journalists shone in one way or another, because we always provide them with an editorial task and a press card with our media title and the names of the journalists. None of us ever thought about going anonymous because we never thought we were doing something illegal, even if our activities are formally against Russian law.

Do you, personally and as part of Avtozak LIVE, have to deal with any forms of oppression or state censorship?

MK: I myself am regularly detained by the police in Russia. The last time it happened, on March 6, I was just walking down the street and a police officer recognized me by sight. He said that he remembered me and that it was high time to smash my face. When he brought me to the police station, they told me that if they wouldn’t find any unpaid fines, they would let me go. I in fact did have unpaid fines after the previous protests I was detained at, but, fortunately, the online platform of the State Services failed and did not show them. I was released the same day.

However, I cannot say that our media has been ever repressed at the official level. I was detained because I am known as a coordinator of Avtozak LIVE, who actively participates in protests. Our journalists also found themselves in paddy wagons precisely during the execution of the editorial task of covering the rallies. Lots of people get detained during the rallies, including journalists. There are exceptions, of course, such as our YouTube channel and podcast administrator, Artem Petukhov. The National Guard of Russia and people dressed in civilian clothes were patrolling near his house for several days. They cut off his electricity and water supply to get him out, however, only his mother lived in that apartment. This is how Artem found out that a legal case had been opened against him and he was forced to leave the country. But this had more to do with his political activity than his participation in Avtozak LIVE; he was the coordinator of the Yabloko Party, which is in the opposition, for a long time and actively worked in election campaigns.

Another form of repression that we are faced with is digital. Some time ago we launched our new website avtozak.info, which was disrupted by a DDoS attack after 30 minutes of air time (the last version of the website can be accessed here). We do not have enough resources to restore it now, but we also have another website, avtozak.online, which shows a map of Russia with all the cases of police detention.

On 8 May 2022, right before Victory Day, some political activists shared on their social media that the police came to their place to threaten and prevent them from protesting the next day. Do you know how these particular people were chosen by the police?

MK: When I worked at the Russian nationwide community platform Open Russia, I did a study on the databases of Russian security forces. Since 2005, there has been a ‘Surveillance Control’ database, the existence of which the Russian authorities deny. This is a database of information systems of law enforcement agencies in transport, which allows them to identify those who participated in opposition actions. Previously, until 2015, only so-called potential extremists and terrorists, football radicals, and sectarians were registered there. Since 2018, they have begun to include everyone who was detained at a rally or those who spoke against the government even on social media. Until 2020, the database had between 10,000 and 15,000 records. In 2020 and 2021, after Navalny’s protests, the database was replenished by 50,000 people just in a month, thanks to mass detentions and surveillance cameras on the streets. So, people who were intimidated or had a search warrant in their apartments on 8 May by the police were most likely picked from this database which includes the information about their protest history, and political activity.

As I mentioned, the Moscow police actively use a video surveillance system. Thousands of cameras with a face recognition system, capable of detecting the faces of people even wearing a mask, are installed in the Moscow subway. Photos, where the faces are recognized, are transferred to the police if needed. This system was quite ironically called ‘Safe City’. As a result, unfortunately, it has become common for activists or regular citizens to be approached, intimidated, and even detained right there, in the subway.

Cameras on the turnstiles at the entrance to the Moscow subway.

How would you describe the protest in Russia, where even those who picket just with a white sheet of paper can be detained?

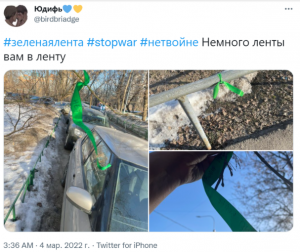

MK: That is true, people are massively detained for even very small actions, such as placing green ribbons on the trees. Before the war started, the State Anti-extremist Center had to monitor the social media feed and search for oppositionists. Now they do not have to search, because the denunciations have become more frequent. Denunciation was a big issue in Soviet Union society, and now, when the society is strongly ideologically divided, it is revived again. Neighbors denounce their neighbors. Still, people continue to protest, just alternatively, quietly. They go picketing, carry flags with them, and do graffiti.

Ribbons were distributed by the Vesna anti-war movement, whose activists were detained last week.

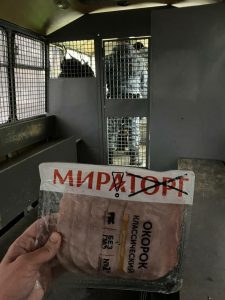

One man went out to protest with a pack of sliced sausage with the Medvedev-owned brand Miratorg and crossed out letters so that the name of it would form the word “peace” (мир in Russian). The policemen literally wrote in their report that this pork sausage discredits the actions of the Russian army. Another man was detained for wearing blue-and-yellow laces on his sneakers. It is absurd, but it leads to serious consequences. What’s more, those who are getting detained are not charged by the court under the law on protests but under the new law on discrediting the armed forces. Punishments for breaching this law are more severe.

Photo: @avtozaklive.

Who or what could be a formative force for a mass protest in present-day Russia?

MK: I think that everyone who could be a formative force of protests has already left Russia. Those who haven’t left will leave soon. All the people who could protest in Russia are already on the streets of other countries. According to OK Russians, a charity group helping Russians who face persecution at home for opposing the war, more than 300.000 people have left Russia in the past months. This number is increasing since it is no longer possible to protest inside the country. Even if Navalny calls to go to the streets again and protest against the war or the government, few people will actually come out. It is a bad thing to say, but the police in Russia work too well. They are very good at intimidation, and this is what they keep doing.