June 26 – August 30, 2022

I have been resisting to return to writing this dispatch for more than two months. Notes – yes, constantly. Writing – occasionally, but not so much. When the tenth dispatch was published in June, I suffered from a two-week-long depression, dark enough I confessed to our School’s Director that I was in the need of psychological help, ashamed and, at the same time, puzzled by my weakness. Many people around me undergo incredible physical and psychological pain, I literally have no reason to suffer, but I do, which makes no sense. Nearly all my childhood friends with whom I was able to reconnect during this year have their kids going through the war grinder – Yulia, Vira, Vita, and Nelya, two of her sons are at the war. The woman at the café, where I stop every morning to get a coffee after jogging, tells me her son is pronounced missing – “Four months! How can one be missing for four months? I told his commander that I saw his dead body on the Russian propaganda channels – I recognized his tattoos, it was him.” My neighbour, Ryta’s father is fighting near Bakhmut. Maksym, one of Ukraine’s known human rights activist, whom I met last September at the conference on media and democracy in Germany, is a declared pacifist who volunteered to the army in the first days of the invasion – he remains in Russian captivity since June, and we learned about it also via the Russian propaganda channels who called him a Nazi, possibly because some time ago he was a producer of a local BBC channel. I watched the interview with his parents, they cope somehow… incredible. When I finished and published my next dispatch in July, the darkness returned. Will it spare me this time? Will see.

In February and March, I recall, writing dispatches was a remediation that gave me a cure and structure amid the shock and chaos of the war, but perhaps according to the logic of the pharmakon, even if something cured you once, it may poison you next time. You just never know. Nothing is reliable. A formula of bearing witness emerges: a laborious act of immersing yourself in terror and, thus, feeling precisely what your enemy wants you to feel – the agony. As such, bearing witness is the opposite to any survival techniques amidst the ongoing war, you just take your skin off and press your flesh against the sharpness of uncovered evidence of genocide – you brace yourself and you make sure no online video about the recent exhumation of bodies or abandoned torture rooms escapes you.

But before all that happened… where were we? Where was I before being interrupted by these nonsense pains? On June 26th, the Russian forces changed their tactics. They started shelling Ukrainian cities far away from the frontline. On June 27th, the “Amstor” shopping center in Kremenchuk, where Asia used to shop when visited her hometown, was hit by a rocket. Experts said it was a X-22 missile shot from a Tu-22M3 aircraft from the Kursk direction and that a crowded place with no relation to any military operations was chosen decidedly. Zelensky mentioned “thousands of people” were inside, but Asia texted me surprised by the inaccuracy. I agreed: we cannot afford using numbers metaphorically, not now. In the end, on the morning of June 1st, there were twenty-eight body pieces recovered from under the debris and the list of twenty-one victims of the strike was published by Ukrainska Pravda, with photos. Russian state media claimed the shopping mall was a “training facility of nationalists.” The strike opened a wild season of regular hits on the civilian infrastructure of smaller and larger towns, and cities. Many did not even make the news unless the destruction was entirely sensational. On the morning of July 14th, a missile attack on Vinnytsia was carried out by the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation in the crowded central part of the city. It killed twenty-seven people, among them – twelve civilian women, seven civilian men, seven employees, and visitors of the Neuromed medical center, three minor children, and three officers of the Armed Forces. The missile strikes on Kharkiv and, most recently, on Zaporizhzhia are happening daily.

On July 29th, the Russian forces set an explosion near Olenivka in the Donetsk region at a Russian-operated prison used for keeping the prisoners of war, where many soldiers from Azov were captives. At least fifty Ukrainian POWs were killed as a result and seventy-three were wounded. Russian propaganda claimed there was no explosion. The investigation was led by Steven Seagal himself as an expert on disinformation and ballistics, who was brought in by the infamous Vladimir Solovyov to report on his trip to Olenivka where Seagal investigated the site to conclude that it was hit by a HIMARS strike, which, he said, Ukrainian Nazis, following the teaching of Stepan Bandera, executed to silence Ukrainian prisoners from Azov as they just “started talking.” They stood there in the studio, two simulacra of each other, to reveal to their distant audience that “fake news is worse than nuclear weapons.”

To make Ukrainian soldiers speak – in Olenivka and elsewhere – as many witnesses reveal, Russian soldiers and the FSB officers present during the interrogation severely beat and torture them, regularly using electrocution of their bodies including genitals, they break bones, rape, and starve them. In an intercepted call, a Russian solder shares his experiences of torturing captives with his mother, providing the details of extreme violence, and his mother suddenly confesses she would have also enjoyed doing that to Ukrainians, if she were sent here. In a viral video, a soldier of the Russian army, later identified by OSINT activists, cuts off the penis of a Ukrainian prisoner of war with a stiletto, then kills him and posts the video on social media. This war has unleashed violence I could only associate with some rare cares of mental disorders or medieval prisons where the executioner believed to be dealing with bodies possessed by the devil and so he had to carve him out of the flesh by any means. Now the executioners are equipped by the modern knowledge of anatomy and the electric current. Most likely, witnesses believe, Olenivka saw that kind of extreme violence where Russian servicemen and representatives of the occupation administration decided to burn the bodies of Ukrainian prisoners with a flamethrower rather than leaving them as evidence of their executioners’ techniques. The report on the Olenivka explosion by BBC-Ukraine, although it does not provide much detail, still provides you a warning: “this article contains information that may upset you.”

In mid-July, the Russian core propaganda show Вечер led by Solovyov hosted the RT editor-in-chief, Margarita Simonyan, who, in her usual manner, announced that Ukraine has no right to exist. Solovyov then supported her by offering the audience a genocidal joke, now a popular genre on Russian state media, by which he explained a radical disconnect between the terms by which different sides describe the Russian invasion of Ukraine. “When a doctor treats a cat to exterminate parasitic worms in her body, for a doctor, it is a special operation, it is a war for worms, and for a cat, it is purification.” Simonyan, whose media corporation RT has been shaping the understanding of Ukraine’s politics among the progressive West for more than twenty years, really liked the joke.

On July 7th, the Ukrainian soldiers of the 73rd maritime center of the armed forces returned the Ukrainian flag to Zmiinyi (Snake) Island, which was under Russian control for a few months. It felt the war started going circles as this strategic point in the Black Sea was one of the first important gains for the Russian army in the first days of the war.

On July 9th, Zelensky dismissed Ukraine’s ambassador to Germany Andriy Melnyk, allegedly for his aggressive approach to securing military support from Germany, and strident attacks on Olaf Scholz and other German officials. Probably not the best strategy in the times of war when you need to beg for all kinds of support, but for the public, Melnyk performed a good service by reminding us how little Europeans thought of Ukraine and how ready they were to stay with the Russian Federation despite the invasion. Half a year into the full-scale war, there is a sense that Ukraine’s resistance has become, and is still growing more and more uncomfortable for the world powers and their inter-imperial economic deals. If indeed Putin’s three-day blitzkrieg would have somehow succeeded, everyone would have taken it just fine – an inevitable development of imperial business as usual. Putin let them all down – China, Germany, France, and others – but not by his imperial war, only by his failure to deliver a fast victory that was promised. And now, by the end of September, even Xi Jinping must perform distancing from Putin in public. According to Melnyk, on the first day of the invasion, German Federal Minister of Finance Christian Lindner told him with a polite smile that Ukraine had just several hours left before it would be occupied by Russia with a puppet government installed, so that any help such as supplying weapons or excluding Russia from SWIFT, he thought, was pointless.

By the end of July, the situation with my parents felt more difficult than when my mother had a broken spine in hospital last year. On the day when we have an appointment with a neurosurgeon, my mother calls me at 6:30am and asks if I could come help her with making pickled cucumbers for the winter. “Now”? I ask as I got up at 4:30am with the hope of finishing a ridiculously overdue essay that was blocking another twelve writing projects. She says, “Now, I have already started on it.” I rush to my parents and find her standing amid the kitchen, while my father, in bed, calls her to give him a nitroglycerin pill because he cannot breathe. She looks dramatically lost and with her face twisted from her own pain in her legs and back. I help my father by turning him on the bed, so he stops sobbing, then I raise this 120-kilo man to help him sit, as he keeps opening his mouth as though he is singing a song, but with the sound turned off. I bring him water and a pill of nitroglycerin that, I know, is killing him, but he refuses to take anything else. Then I return to the kitchen. I ask my mother to sit and tell me what to do. She obeys. I go to the garden and pick several sets of leaves – grape, sour cherry, mint – as well as parsley and dill, wash them and put on the bottom of two 3-liter glass jars along with garlic, dry bay leaves and black pepper.

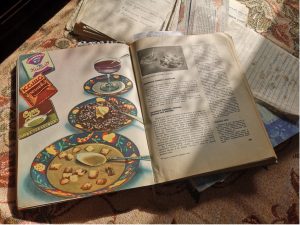

The air raid sirens, all three of them, go off. My mother tells me they could not sleep all night because the sirens were too loud. I wash the cucumbers, cut their ends, and put them in the jars, then after I cover them with greens, I turn to prepare the salty water. I pull the pack of the precious Artemsil salt from the shelf, the price of which actually did go up three times since my last dispatch, but my mother cannot recall how much salt is needed. I suggest looking it up online, but she wants “that” recipe she always used and no other. She is extremely upset, she says, she never could imagine that she would forget such things as the amount of salt needed for pickled cucumbers – “it’s time to die.” She stands up, pain-twisted face, and heads to the room where she would look for the recipe. Within the next hour she looks through all her life-long records on cooking – many of which I recognize from my childhood, and the memories of eating those cakes, and salads, and soups run through my mind, but the pickled cucumber recipe does not surface. The last place left to look, she says, is the Book of Tasty and Healthy Food, a Soviet collection of culinary recipes and food-preparation hints, first published in 1939 and approved by the USSR Ministry of Food, edited by the father of the Soviet dining industry, Bolshevik commissar Anastas Mikoyan, who, as we all knew back then, met Lenin himself in 1919 – somehow it mattered.

One hour later my mother enters the kitchen to let me know it’s 2.5 full spoons of salt per jar; I make the salty water, pour it in the jars, take two hard lids sitting in the pan on the stove, put the lids on, and we are done. The air alert is cancelled, too, and I run home to catch up with work.

My father resists my help, he forces my mother to perform housework she is not capable of doing. I spent time with them every day, 4-5 hours, but it is not enough in a house without hot water, where even washing dishes is a very complex procedure of carrying water in metal bowls from the bathroom, heating them on the stove in the kitchen, bringing a hot bowl to the kitchen table on the other side of the room, washing dishes in two containers, pouring water into a plastic bin and taking this bin outside to the garden to dump it under the apple tree. My father does not accept any alternative procedure. My suggestion to set up hot water in the house, which I can easily arrange by calling Vodokanal, is not accepted. This whole process is impossible for someone like my mother who has a disabled arm since childhood, and now, my father cannot do that as well, because he cannot take a step without two canes. Groceries, utilities, and everything that concerns hospitals and medication are on me, and the main weekly cleaning of the house and yard once a week, every Saturday at 7am.

Why Saturday at 7am? It is because during his service in the Soviet army in the navy they did the cleaning of their ship at 7am. The army structured the mind and psyche of this young Ukrainian peasant for the rest of his life. Prior to that he was literally nobody, he did not even have a passport (since passports under the Soviet feudalism were not distributed among villagers to keep them attached to collective farms without a possibility of moving elsewhere), but then, in the 1950s, he was taken to Leningrad, given the profession of a cook, and a beautiful marine uniform – blue and striped. When I recently took him to a dentist, right in the dentist chair, he suddenly revealed another detail of his miraculous transformation I never heard before: it was in the army that he cleaned his teeth for the first time in his life and was rather surprised by how white his teeth were; there, he also discovered his hair was curly after washing it with shampoo. You cannot undo that.

Doing laundry at my parents’ is hard even for me: I am still grasping all nuances of setting that washing machine to work in a slum house without hot water and proper distribution of cold water – you either have to be an engineer, I think, or really, really determined, like my father is, to have water for free by hacking the water infrastructure with your complex system of hoses and wrenches, connecting tubes that are not normally connected, for each of your laundry cycles. Same for taking a bath. On Tuesday, September 6th, we planned that adventure. After filling a bathtub with water, which was preceded by playing with gas tubes that I had to re-connect in a specific way, I helped my mother to walk to the bathroom. Even with my help she barely placed herself on a seat above the tub water and was not even able to spread soap over her chest. I carefully washed her tiny body with a soft sponge, trying not to irritate her incredibly thin skin. “I am so glad you do not despise doing it, Sveton’ka,” she said, “this is my last bath, my dear, I do not think I can do it again.”

I come to help with housework every day, but even washing dishes must be done three times daily, which is not possible with my work schedule and load. It’s crazy to watch my father trying to wash dishes himself, holding a metal bowl with hot water in his hands and leaning towards the wall by his back, which allows him to make small side steps until he reached the kitchen table and places the bowl on it. Sometimes he succeeds, sometimes he does not and then all hot water spills on the floor and on him; his skin is thick enough to bare that, so it seems, but collecting the water from the floor is another matter. Instead of peaceful rest, which my mother needs the most now, she is destined to sit on the kitchen chair and watch this insane drama of him moving along the wall with a bowl of hot water, cursing his body, his doctors, his life, and her with the dirtiest words he knows. “I just do not answer,” she tells me, when she recalls these episodes in our quiet chats. “Nobody loves me,” she says suddenly, and I realize that his abuse blocks even the love I am here to give her – my love does not reach her anymore.

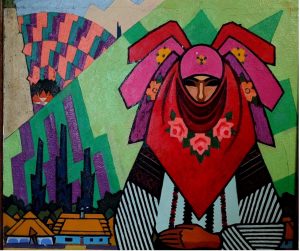

In June, I met Svitlana from Kyiv who had already lived for several months in Kamyanets since the invasion. She is a former PR manager of our major rock band Okean Elzy, and I say that because she does when introducing herself, her work for the band is one of her great achievements, everyone knows that, but I know that she is so much grander. Her energy, and her drive at first almost scared me, but then, after several dinners together, we synched into a perfect unit of travellers waiting for those Saturday and Sunday mornings, jumping in her car, and rushing towards villages, rivers, and mountains of our region – Bakota, Krushanivka, Maliivtsi, Yaruha… towards the landscapes painted decades ago by our most known local artist Oleksandr Gren, whose works I remember from my childhood visits to a gallery in the Old Town, and where I went to see them again inspired by our travels and conversations about his unique way of depicting the landscapes of Podillia. Gren’s portrayal of Podillia women is known for documenting how six or seven scarfs were traditionally worn one on another and under the chin. These Podoliankas are assumed to be self-portraits – but the matter of his homosexuality is what the gallery guides only whisper about and not to all visitors.

It was in that gallery in mid-August that I met Natalia Svyrydiuk, our known and honored Ukrainian artist from Poltava, who also escaped the shelling of her city in Kamyanets-Podilsky, and whose exquisite reconstructions of traditional Ukrainian dolls were exhibited there. We met for drinks one evening at a newly opened bar in the Old Town, and I asked her if she’d make a traditional knot doll – for me. I wanted it to be Gren’s Podolianka from the paining, only scary as hell and filled with rage – a Gorgon with those scarfs as venomous snakes, a Vodou doll that can turn our enemy to ashes. Natalia is excited. She accepts the job that will take until November.

We do not talk about war with my parents anymore. Only when air raid sirens go off too often at night, my father cannot sleep and complains to me in the morning; or if someone we know is killed or wounded at the front. Missile strikes still do not reach us. In July, the exact day now escapes me, four rockets were shot down by our defence system near our town, and that was the most. Our attention was then preoccupied with the possibility of chemical and nuclear attacks. In the beginning of August, the government updated the Air Raid Alarm app by differentiating threats and signals: air alarm, shelling, street fights, chemical threat, and radiation danger.

A peculiar disinfo was spreading through various channels in western and south-western regions, including mine: the signal of chemical danger, it claimed, would be associated with the sound of church bells, the signal of radiation danger with a bell, and the signal to evacuate the city with a train horn.

Closer to Independence Day, August 24th, staying at my apartment during sirens was not comfortable again, and the sirens were constant. The expectation of a potential nuclear strike was also set, and it felt quite possible, as it does again now, at the end of September. I spent the month of August preparing my tenure file for a September 1st deadline but had to also do more reading on radiation to get a better idea of what to do if that happens and how many drops of iodide to drink with water for thyroid protection during nuclear or radiological emergencies since the pills are not available at drug stores. Then there was the info that family doctors in our town are giving pills to anyone under forty. I texted Yevhen, my biologist friend, to clarify the age restriction, and he sent me this: “The thyroid gland produces iodine-containing hormones thyroxine and triiodothyronine. These are very ancient hormones that are responsible for both growth processes and the intensity of metabolism. With age, the intensity of metabolism decreases, and the processes of renewal of structures slow down. The hormone is produced less. In addition, the gland deposits large amounts of iodine, spending little of it in adulthood. Accordingly, less dangerous isotopes will reach a less active gland, and the risk of internal radiation is lower. Excessive iodine overdose can have harmful consequences. Which ones I won’t say now, I have to search more on that. But, in general, our bodies adapt better to a lack of something than to an excess. Although there may be significant individual variations. Your biological age seems to allow the active functioning of the gland, but doctors are focused on the average norm. If this fundamentally confuses you, you can do certain analyses, studies of the state and functional activity of the gland, and based on them, think of more individual recommendations.” A bottle of iodide is still on my bedside table.

On August 23rd, I was nervous, even, panicked. I spent the day writing a text for ROOM: A Sketchbook for Analytic Action, a New York-based magazine, which calmed me down. Then I went towards a river canyon with Olya, a friend of my friend, whom I rediscovered for myself recently. On August 24th, I did not feel a thing.

For a month already, I go jogging with Olya in the mornings at 6am, when it’s still a complete darkness, and I run to meet her through a local cemetery, which is quite a challenge, especially in the rain, as its trails are extremely muddy. Our route then goes around the local city park, the site of the Kamyanets-Podilsky massacre, a World War II mass shooting of 23, 600 Jewish people, both locals and deportees, only within two days of August 27th and 28th in 1941, with the pace exceeding that in Babi Yar, carried out in the opening stages of Operation Barbarossa, by the German Police Battalion 320, Friedrich Jeckeln’s Einsatzgruppen, the Hungarian soldiers, and the Ukrainian Auxiliary Police. I always wonder if anyone thinks about what happened there on the site eighty years ago, after decades of repressing this story by the Soviet government. I always wonder what or who stopped the project of building a housing complex there. The way these graves survived is a secret and it is buried in history. After we do our 6km, we make our way down to the canyon, again through another Jewish cemetery, where the Nazis later threw the bodies of exterminated Jewish kids, I pick up the garbage if the local public leaves it near the graves, and we walk towards a marvellous field of various herbs and flowers down near the riverbank. They were always just “grass” to me until I learned more about the local flora on our trips with Svitlana this summer; the complexity of their symbiosis is felt through their explicit presence so that you always want to ask permission before entering their field.

On August 30th, I woke up at 2:11am, because someone said “Ukraine” right into my ear. It was the voice from CBC News, which I left on while falling asleep, “Ideas” by Nahlah Ayed was running, the program about Jewish and Palestinian music with the anchor interviewing a group of musicians. “We will leave you with one more piece of music,” she said to the radio audience, “the band’s 4th quartet was inspired by this song.” And I hear a Ukrainian folk song “They are carrying a Cossack” performed by Capella Dumka. I fall asleep and dream of my mother and I standing on a thin trail on the edge of a cliff beneath us. Along with others, we are slowly moving forward. But when at one point I turn around, I see her left behind – with many people stepping carefully hands pressed against the cliff between us. I cannot make a step towards her, nor I can even call her without disturbing everyone, so I don’t – we just look at each other silently, but suddenly I see her eyes – very close – as even the distance between us has folded – and I wake up to hear Inuktitut coming to me through another CBC channel – somewhere from the Canadian Arctic.