“There are rarely good reasons for showing us the images of mutilated victims” Harun Farocki[1]

“Those of you who, despite the flood of death images, choose not to bear witness but instead act as mere spectators, beware that you are passing through our bodies, walking over our bodies, and standing on our bodies,”[2] wrote Lebanese artist Alaa Mansour on her Instagram in autumn 2023 during Israel’s devastating attacks on Palestine. Later she deleted her post but I still keep a screenshot of it, and keep thinking of her words.

The image she posted along with those words was a blank white square with the word “image” written in Arabic. It is an image where there is nothing to look at, nothing to see. Does it mean that bearing a witness is something opposite to looking?

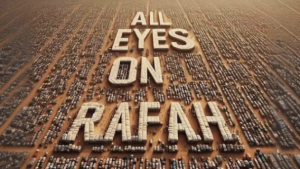

In contrast to Alaa Mansour’s post, the AI-generated image “All Eyes on Rafah” (created by a Malaysian artist known by his username @shahv401) massively circulated on the Internet suggests that looking at the violence can somehow stop or prevent it. This picture has been re-shared over 46 million times on Instagram since Israel’s deadly attack on the Rafah refugee camp on May 24.

In fact, it offers to us, the spectators, quite a comforting feeling that looking is already a sort of action. This image tells us that If we put our eyes on Rafah for a second, if we donate a bit of our attention, which, as we know is a precious resource today, we will contribute to .. what?

The paradox of “All Eyes on Rafah” image is that, calling us to turn our eyes on Rafah, it in fact directs our eyes away from it. What is being shown has nothing to do with a real place. What we are looking at is some dream-like piece of purely virtual reality. Experts say this is precisely the reason why this image went viral. It is the absence of the real violence that makes it shareable.

“I believe the virality of this image is largely due to its stark contrast with the predominant visual imagery of the war … To humanise the victims in Gaza and Rafah, social media users often share vivid images of casualties and mourning family members,” Eddy Borges-Rey, associate professor in residence at Northwestern University in Qatar, told Al Jazeera.[3] “This might explain why algorithms on platforms like Meta [Facebook and Instagram], designed to filter graphic violence, did not flag this image. Unlike real, graphic images of the war, which might be restricted or removed due to content policies, this AI-generated image could spread more freely, contributing to its rapid virality,”[4] said Borges-Rey. “The AI image might be more palatable to some viewers than real photos of Gaza which are graphic and often show blood, dead bodies and violence”[5], the Aljazeera journalist explains. That kind of images offer us a “healthy way” to look at the pain of others without being negatively impacted by seeing it, a smart option of looking without seeing, a balanced manner of being publicly “engaged” but at the same time mentally detached.

Synthetic Double

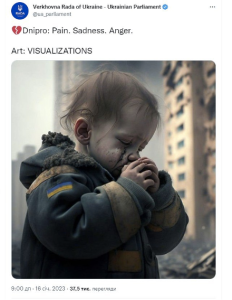

Yet, while some deepfake images of tragedies mitigate the depiction of terror to make it more “palatable” and therefore spreadable, others just simulate it without trying to decrease the level of violence or pain in the image. After the Russian rocket attack on a residential building in Dnipro on January 14, 2023, the Verkhovna Rada (Ukrainian parliament) shared on its Twitter page a deepfake image of a little boy with traces of blood on his sad face, a presumed survivor of the Russain missile attack, accompanied with a caption “Dnipro: Pain. Sadness. Anger”. Unlike, the “All eyes on Rafah” picture it was a close-up aimed at delivering a vivid and graphic depiction of a victim of the strike. That image was widely criticized but also widely circulated. It was deleted from the official page of Verkhovna Rada 20 minutes after the publication under the pressure of critical comments, but it virally spread out across social media.

The use of this deepfake image to mourn the tragedy by officials as well as random social media users felt to me all the more surreal against the background of the abundance of real photos of the real victims. One particular photo, taken by Arsen Dzodzayev, depicting Anastasia Shvets who survived the rocket attack on Dnipro, sitting amidst the rubbles of her destroyed home, immediately became an iconic image of the tragedy, virally spread across the web. Like the little deepfake boy, the woman is surrounded by ruins, her hands near her mouth, she is absorbed in her own tragedy. This photograph might have been a reference for the synthetic image of the boy. Why wouldn’t the Ukrainian Supreme Council use this well-known photo of the real person and the real consequences of the attack, I wondered?

Anastasia Shvets, who survived the rocket attack in Dnipro. Credits: Arsen Dzodzayev/Hromadske

One of the most alarming objectives behind synthetic images of war is that they are being used by the enemy to spread fakes or propaganda or to blur the line between what is real and what is fake, seeding the confusion, as many critics commented the famous deepfake video of Zelensky announcing the surrender. But why do we use deep fakes to mourn the real victims when we have real photographs of them?

When Ukrainian social media users, following the move of the Parliament of Ukraine, started massively spreading the deepfake Dnipro boy, I asked myself: was it a sign that documentary images of violence don’t seem convincing to us anymore? Was it a symptom of the well-discussed media anesthesia? Are documentary images of violence not impressive or not effective enough, so we are trying to enhance the image of disaster with algorithmic visuality, just like we are improving our selfies with filters?

Russian media theorist Anna Engelhard claims that synthetic images might be more effective than documentary ones. Pointing to the failure of documentary images to stop the violence, she proposes to shift from a representational to an operational mode of visuality: “Indexical image does not suffice as a means to an end – to gain political significance, it must be tied to an action, it must be operationalized as a part of a larger system,”[6] she writes. Referring to the example of the fighter jets’ head-up displays (HUD), which substitute the real view of the pilot with the simplified target map to avoid his distraction with unnecessary details, she rightly suggests that “simulated image becomes more tactically useful than the real one.”[7] It always was. Synthetic images aimed at simulating reality are operational by design just because the very technology of simulation was developed to operate reality. The example she picked is a telling one as it highlights the core method of simulation production: stripping the reality of unnecessary details and keeping only the key characteristics crucial for the given task, just like reducing the territory to the set of targets.

Unnecessary Details

In 2022, the first year of the full-scale Russian invasion, Ukrainian artist Anna Zvyagintseva made a work called The Same Hair. It consists of a screenshot from her online conversation, namely a question “How are you?” addressed to the artist by someone allegedly from abroad, and her response to it: “Air raid sirens sound all around Ukraine now. I didn’t know I can feel hatred so deeply. I saw a photo of a dead kid, who had the same hair as my daughter has.”[8] The work’s second part is a picture of her daughter with her face covered under her beautiful hair.

To be honest, when I first saw this work on Instagram I felt pissed off at Anna for using her daughter’s image as a part of it. I still find it difficult to look at this work, just because I also have a daughter, almost the same age.

This work points directly to the difference between a photograph and a synthetic image. This difference lies in the details, those random manifestations of reality, which don’t have a generic meaning but can gain significance from some peculiar point of view. Rolan Bart called such detail speaking personally to the viewer “punctum”, comparing it to “studium” as a more common layer of meaning.

At the dawn of photography (coming to its decay in front of our eyes) Walter Benjamin grasped the revolutionary particularity of the new medium: “No matter how artful the photographer, no matter how carefully posed his subject, the beholder feels an irresistible urge to search such a picture for the tiny spark of contingency, of the here and now, with which reality has (so to speak) seared the subject.”[9]

The “tiny spark of contingency” is exactly some uncontrolled detail, unnoticed by the photographer and not serving his or her aims, where reality left its mark, its message addressed to some unknown future beholder. Like the hair of the dead girl captured by the camera sent a message directly and specifically to Anna, leaving a trace in her vision of reality. Now, looking at Anna’s work I involuntary adopt her vision, a mother’s view of her daughter seeing her beauty; this vision is very familiar to me; only this time Anna made me look through the eyes of a mother seeing her child as a potential victim, and I was angry at her because that vision was unbearable.

These kinds of details are exactly what synthetic image lacks. This lack makes them for us more ‘palatable’, as an AlJazeera journalist puts it. This is why the deepfake violence, no matter how graphic, is not unbearable. Just because reality didn’t leave its mark there. The synthetic image of the Dnipro boy doesn’t have any contingent details, except for glitches. This image is generic. It is a generalized image of the victim. This boy has nothing to do with my child because they don’t share the same reality. This deepfake image can convey the message of violence but this message doesn’t hit me directly because the violence, a real one, is rendered as fiction.

Witnessing vs Looking

Contingent details are what made photography, from its very beginning, so attractive to forensics. French criminologist Alphonse Bertillon, who started using photography to document crime scenes, explained the benefits of the medium compared to human unmediated vision. “You only see what you look at and you only look at what you want to see,” [10] he said. Instead, metric photographs of the crime scene dispassionately register all details, even the most insignificant or those that at the moment seem insignificant to the eyewitness, although later, in the process of investigation, they may turn out to be key. As Benjamin said more poetically and more politically, photography invites us “to find the inconspicuous spot where in the immediacy of that long-forgotten moment the future nests so eloquently that we, looking back, may rediscover it.”[11] This inconspicuous spot might reveal itself only later, apart from the moment when the picture has been taken, in the process of investigation, or under the light of some subsequent events.

In the last paragraph of “Little History of Photography,” written “in a decade heavy with the threat of Fascism,”[12] Benjamin famously claimed that every photograph is a photograph of a crime scene:

“It is no accident that Atget’s photographs have been likened to those of a crime scene. But isn’t every square inch of our cities a crime scene? Every passer-by a culprit? Isn’t it the task of the photographer -descendant of the augurs and haruspices- to reveal guilt and to point out the guilty in his pictures? “The illiteracy of the future,” someone has said, “will be ignorance not of reading or writing, but of photography.” But shouldn’t a photographer who cannot read his own pictures be no less accounted an illiterate?” [13]

The illiteracy of a photographer, according to Benjamin, is his inability to recognize the traces of crime in the photographed scene and detect the criminal who left his footprints there. With this passage, which always seemed too dramatic to me until recently, Benjamin managed to trace the new emerging relationships with the visible, brought by the medium of photography. The reality, grasped dispassionately by the mechanic eye in details, became exposed to endless scrutiny, investigation, and revelation, disclosure of what was hidden, and discerning of what was unnoticed. This rediscovery of reality as more accessible for profound inspection came along with new hopes for justice, expressed by Benjamin. “Photographs furnish evidence,”[14] Susan Sontag wrote, almost 50 years later. “In one version of its utility, the camera record incriminates… In another version of its utility, the camera record justifies. A photograph passes for incontrovertible proof that a given thing happened,”[15] Sontag still believed in 1977.

Unlike photography, synthetic images neither incriminate nor justify, it’s not proof that a given thing happened. Synthetic images of real violence, whatever graphic they are, don’t deliver us any evidence of it, so we can look at it without witnessing it. They don’t contain any details that can serve for future investigation. They don’t imply any investigation at all. Neither do they imply any responsibility or justice.

If the arrival of photography brought to us the idea of an image as evidence, the arrival of synthetic images marks the shift to another visual paradigm: the visible reality is not to be explored, but to be governed. Within this paradigm, the images are not to witness, reveal, or expose, but to operate.

Unlike photography, synthetic images of a crime don’t document a crime scene anymore. Synthetic images of war crime victims don’t contain any footprints of the criminal, only the message of victimhood. They don’t contain any data, which can be used for future justice. They can convey the message of violence without bearing any evidence of it. Just like proxy military units, they do their job without leaving any legally recognizable traces.

Plausible Deniability

Remember “little green men”, harbingers of Russo-Ukrainian war? Mysterious men, with covered faces in unmarked green military uniforms and fully equipped with weapons, appeared in Crimea just before the annexation in 2014.

Their presence clearly signaled the beginning of the Russian military invasion, but at the same time ensured not to provide sufficient evidence of it. Have a look at this picture of little green men taken by Reuters photograph Vasily Fedosenko in Crimea in 2014, it looks already like a synthetic one. The figure e of a little green man is a sign of pure violence, stripped of any specific details, except for a manifestation of force.

Credits: Reuters/Vasily Fedosenko

As Wikipedia puts it, “Russia, which had been denying any involvement in Ukraine prior to the annexation, used these little green men to give it plausible deniability on the international stage.”[16]

According to the Cambridge Dictionary, plausible deniability is “the ability to say in a way that seems possibly true that you did not know about something or were not responsible for something.”[17] According to The Law Dictionary “Plausible means you could conclude that something might or might not be possible”. In other words, plausible deniability is the ability to act in a gray zone, where multiple interpretations are possible. It’s not about proving or convincing that you are not guilty, but about leaving the space for uncertainty. Web is a perfect environment for this kind of strategy.

As digital culture theorist Valentina Tanni wrote in her brilliant recent book, “Exit Reality” “it is no longer just question of having to deal with misinformation or combating the advent of a culture increasingly focused on an emotion-flued, biased interpretation of reality, but rather of facing up to a social horizon in which truth and falsehood are not – and never again will be – distinguishable in an absolute sense.”[18]

In the last paragraph of the “Little History of Photography,” Bejmanin wrote: “The camera is getting smaller and smaller, ever readier to capture fleeting and secret images whose shock effect paralyzes the associative mechanisms in the beholder. This is where inscription must come into play […] without which all photographic construction must remain arrested in the approximate.”[19] This is exactly what happens to the image on the internet: it is arrested in the approximate, although not because of the lack of inscription but because there a myriads of inscriptions for every image. Within this kind of environment, there is always room for plausible deniability, which means that even the documentary image has the structure of a deepfake. Images of violence don’t function as evidence anymore because there is always a plethora of contradictory interpretations around them linked to very different versions of reality. Yet they are operational. While the specificity of meaning is lost in the gray zone of uncertainty, the sedimental meaning of threat and dominance can still be effectively delivered.

Successful Business Model

As it is well known today, the major part of “the little green men” were mercenaries from the Russian proxy military unit Wagner Group, famous for their extreme cruelty and extensive media presence. “The Wagner Group, officially known as PMC Wagner is a Russian state-funded private military company (PMC) controlled until 2023 by Yevgeny Prigozhin, a former close ally of Russia’s president Vladimir Putin,”[20] states Wikipedia. “State-funded” means that it fulfills state orders and is paid with the Russian taxpayer’s money. It also means that it uses the infrastructure of the Russian Armed Forces. “Private” means that the organization is registered in Argentina, and that although the connection of Wagner to Russia is obvious the Russian state can still deny its responsibility for the Wagner deeds. Or, to be more precise, the state-funded but private structure of Wagner PMC allows the Russian state to simultaneously show off the group’s activity as its achievement and deny responsibility for it.

PMC Wagner showed up for the first time at the beginning of the Russo-Ukrainian war in 2014 during the annexation of Crimea and the invasion of Donbas. By now it has operated in at least 10 countries: Belarus, Ukraine, Syria, Sudan, Mozambique, Central African Republic, Mali, Libya, Venezuela, and Madagascar. In most cases, their task is to support local dictatorships in exchange for resources and loyalty to the Russian state.

“Someone point to Syria as a highly successful model of how business could be done,”[21] says Candace Rondeau, Wagner expert from Arizona State University, in the Wall Street Journal documentary about the group. In Syria, Wagner backed the Bashar al-Assad regime, and even though they suffered heavy losses, the operation proved to be profitable as they got from the Syrian government oil and gas drilling rights to about 10,000 miles of land across the country. This “successful business model” was immediately replicated and sold to a range of African countries, enabling Russia to take control over a growing amount of African resources such as gold, diamonds, or lithium.

“As it later turned out, the practice of beheading enemies, burning their bodies, cutting off their limbs, and filming the whole thing started for PMC Wagner in Syria and Africa. Back then, this wasn’t yet intended to become the company’s official doctrine and was still hidden from investigative journalists. […] After February 24, 2022, everything fundamentally changed. Horror […] became a powerful promotional campaign for Wagner[22]”, writes Stanislav Aseyev, Ukrainian soldier, writer, and former war prisoner.

After February 24, 2022, when Wagner PMC took the leading role in the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the group’s brutality became a trademark of the Russian military style. “The PMC is no longer limited to making war or business: it is also involved in a broader strategy of branding Russia in the eyes of foreign, as well as domestic public opinion[23]”, Marlene Laruelle and Kelian Sanz Pascual claim in their article “The Wagnerverse: Pop culture and the heroization of Russian mercenaries” for Russia.Post. “At a time when mercenary activity has been propelled to the forefront of the international scene”, they wrote, “Russia has certain advantages and a brand image” in this market.[24]

“What’s “unique” about Wagner is that—unlike the Russian state—they don’t renounce their cruelty, they advertise it instead and turn it into a cult”[25], writes Aseyev.

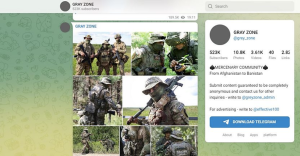

Thanks to its proxy army the Russian state can simultaneously renounce its cruelty and make it a part of its brand. At the same time, plausible deniability is also a fundamental principle of the Wagner PMC media campaign. It’s not by chance their main Telegram channel is called “Gray Zone”.

Gray Zone

One of the most famous videos produced and distributed by PMC Wagner was the video of the execution of its former fighter Evgeniy Nuzhin with a sledgehammer for alleged treason. This kind of execution video is usually shown by the PMC’s recruiters to their potential employees to ensure discipline. They call them “educational videos.”[26] Yet, this particular video was designed to be distributed to a wider audience. It was published on the night of November 13, 2022, on the “Gray Zone” Telegram channel and immediately became viral on the web, receiving billions of views on TikTok.

The video starts with clips from Nuzhin’s interview, where he claims to have voluntarily surrendered to join Ukraine’s side. The scene then shifts to Nuzhin lying on his side with his head taped to a stone. Moments later, someone off-camera strikes Nuzhin’s jaw with a sledgehammer.

Dmitry Peskov, the spokesman of Vladimir Putin, when asked about the incident, answered, following the logic of plausible deniability that the Kremlin doesn’t know whether it is true and that “This is not our business.”[27] Instead, the press service of Prigozhyn, the then leader of the group, distributed his comment on the case: “I think this movie is called “Dog’s Death to a Dog”. Excellent directorial work.”[28]

On Feb 13, 2023 “Gray Zone” posted a similar video featuring another Wager’s fighter, Dmitry Yakushchenko executed in the same way. Prigozhin again called this video a film, claiming it is a film series. “If you wish, we can share the next episode with you,” he said.[29]

Clearly, spreading the fear-inducing videos is a part of Wagner’s media campaign promoting its threatening image as a merciless, ruthless force. At the same time, both videos were repeatedly claimed to be fakes produced by the Ukrainian side, to ensure the space for deniability. In this case, it is not a fake image pretending to be true, but rather a truth delivered in the form of a fake; a kind of fake which should nevertheless be taken seriously.

Just as a PMC Wagner’s itself, the images of the violence committed by them, operate within a gray zone, where the boundaries between fact and fiction, truth and fake are blurred, and everything is uncertain, yet the message of coercion remains precise.

After the success of the sledgehammer video, regardless of whether it was true or fake, the hammer became a mem widely used by Wagner. On January 2023 leader of the party “A Just Russia – For Truth” Sergei Mironov posted on his Telegram channel a photo of himself holding a sledgehammer with the depiction of a mountain of skulls and the inscription “ To Mironov from PMC Wagner. Bakhmut-Soledar”.

Earlier, in November 2022, a similar sledgehammer smeared with fake blood, packed in a violin case was sent by Wagner to European Parliament in response to the resolution its resolution identifying Russia as a “state sponsor of terrorism”.

Russian BBC journalists called this gesture a performance,[30] placing it again into some elusive fictionalized space. But even if the blood was fake those who sent it were real and their message was clear. The previously released video of the Nuzhin’s execution functions as a decoding instruction to this message. This message is, as they say, ‘educational’, designed to teach using blackmail and intimidation.

All Eyes On

In his famous essay on necropolitics, Achille Mbembe claims that coercion became a market commodity[31] in the contemporary world of the global economy, hooked on extractable resources. In this market of coercion, “Russia has certain advantages and a brand image” due to Wagner, as we already know.

If the business is trading violence, then any showing of the committed violence is a promo. That is a reason why the mercenary practice of Wagner is inextricably linked with the practice of image production. Look at this still from the video released by Prigizhin’s press service on March 2, 2023, with the Wagner fighters standing with a flag and musical instruments on top of the destroyed building in Bakhmut, Ukraine.

This is an image promoting an effectively accomplished task. If you need to erase any traces of life in a certain place, don’t hesitate to reach out. The brutality of Wagner’s operation on the ground is crucial to ensure the powerful brand image needed to maintain the advantage in the competitive coercion market.

Due to the marketing logic, any new reports, documentaries, or reportages featuring the violent actions of a coercion trader are beneficial for its business. The more visibility, the more profit. Wagner’s business in Africa flourished during the extremely brutal and extremely visible war in Ukraine. As Aseyev said, after February 24, 2022 horror became a powerful promotional campaign for Russia, which continues to pay off with African resources. A gray zone of the web is a favorable environment for such a campaign. While the evidential value of the images of committed crimes is lost in the clouds of uncertainty, they can perfectly operate as an advertisement of the abuser’s brutality, power, and in most cases impunity. And advertisements, as we know, need our attention. It needs our eyes on it. Synthetic images of war crimes just continue this advertising strategy; they effectively eliminate any evidential or forensic footprints of committed violence turning it into a visually catchy perfectly spreadable promo.

***

Just to remind you, the “All Eyes on Rafah” campaign started with the documentary satellite image of Rafah posted by the Palestinian Feminist Collective on their Instagram page on February 12 accompanied by a text: “Two days ago, after four consecutive months of continuous colonial violence, the Zionist regime ordered 1.5 million displaced Palestinians to “evacuate” from Rafah, initially deemed a “safe zone”. Those who tried fleeing to Deir al Balah were received with bullets from the Occupation’s snipers on the road, while over a million stayed in Rafah sheltering in mosques, schools and makeshift tents. Currently, over a million Palestinians sheltering in Rafah are under US-backed airstrikes.”[32]

This image was circulated to signal the ongoing violence and, at the same time, as a kind of action of preempting or forestalling the expected even more brutal violence. The following deadly strike happened with our eyes on it. We still keep watching.

—

Notes:

[1] Harun Farocki, Phantom Images, p. 22, chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://monoskop.org/images/f/f8/Farocki_Harun_2004_Phantom_Images.pdf

[2] Alaa Mansour (@alaa_ma), deleted Instagram post

[3] Sarah Shamim, ‘What is ‘All eyes on Rafah’? Decoding a viral social trend on Israel’s war’, Aljazeera, 29 May, 2024, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/5/29/what-is-all-eyes-on-rafah-decoding-the-latest-viral-social-trend

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Anna Engelhardt, ‘Fear of the Synthetic Image’, Militant Media, Centre for Research Architecture, 2024, p. 158

[7] Ibid., 152

[8] Anna Zvyagintseva, Tha Same Hair, 2022, http://annazvyagintseva.com/contact/the-same-hair/

[9] Walter Benjamin, Little History of Photography, Selected Writings, Volume 2, Part 2, 1931-1934, p. 510

[10] Paul Virilio, The Vision Machine, British Film Unstitute and Indiana University Press, 1994, p. 42

[11] Walter Benjamin, Little History of Photography, Selected Writings, Volume 2, Part 2, 1931-1934, p. 510

[12] Jeremy Tambling, “City Snapshots: Walter Benjamin’s “Little History of Photography””, Springer Link, 19 April, 2018, https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-3-319-62592-8_38-1

[13] Walter Benjamin, Little History of Photography, Selected Writings, Volume 2, Part 2, 1931-1934, p. 527

[14] Susan Sontag, On Photography, RosettaBooks, 2005, p.3

[15] Ibid.

[16] Little green men (Russo-Ukrainian War), Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Little_green_men_(Russo-Ukrainian_War)

[17] Plausible deniability, Cambridge Dictionary, https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/plausible-deniability

[18] Valentina Tanni, Exit Reality, NERO, Aksioma, 2004, p.206

[19] Walter Benjamin, Little History of Photography, Selected Writings, Volume 2, Part 2, 1931-1934, p. 527

[20] Wagner Group, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wagner_Group

[21] The Wall Street Journal, Inside Prigozhin’s Wagner, Russia’s Secret War Company, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EMXnJMCoFYI

[22] Stanislav Aseyev, “Apocalypse Now?”, Krykyka, 2023, https://krytyka.com/en/articles/apokalipsys-sohodni

[23] Marlene Laruelle, Kelian Sanz Pascual, “The Wagnerverse: Pop culture and the heroization of Russian mercenaries”, Russia.Post, 28 June, 2022, https://russiapost.info/politics/wagnerverse

[24] Ibid.

[25] Stanislav Aseyev, Apocalypse Now?, Krykyka, 2023, https://krytyka.com/en/articles/apokalipsys-sohodni

[26] BBC News – Русская служба, “Казни, шутки и «мясные штурмы»: как Евгений Пригожин устроил свою ЧВК «Вагнер»”, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sYhEk2g3N4g

[27]Радио Свобода, “Песков о казни заключённого из “ЧВК Вагнера”: “Это не наше дело”, 14 November, 2022, https://www.svoboda.org/a/peskov—o-kazni-zaklyuchyonnogo-iz-chvk-vagnera-eto-ne-nashe-delo-/32130626.html

[28] News.Ru, “«Собаке — собачья смерть»: Пригожин о казни бывшего заключенного Нужина”, 13 November, 2022, https://news.ru/society/sobake-sobachya-smert-prigozhin-ocenil-ubijstvo-perebezhchika-iz-chvk/

[29] Lenta.Ru, “Пригожин отреагировал на видео с казнью кувалдой бывшего вагнеровца”, 13 February, 2023, https://lenta.ru/news/2023/02/13/commentarr/

[30] BBC News – Русская служба, “Казни, шутки и «мясные штурмы»: как Евгений Пригожин устроил свою ЧВК «Вагнер»”, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sYhEk2g3N4g

[31] Achille Mbembe, Necropolitics, Duke University Press, 2019, p. 84

[32] @palestinianfeministcollective, February 12, 2024, https://www.instagram.com/palestinianfeministcollective/?hl=en