Comment sections on social media platforms have evolved from a tool to respond to an online post, into ‘third spaces’, meaning they have become social spaces where we connect that are neither home nor work. They can, at times, be volatile due to the nature of communicating behind a screen as opposed to IRL. Much of the culture wars are being fought online, which has led to a simplification of complex issues and ideas reduced to binary arguments. The creation of the Internet is an incredible contribution to global communication and has pushed forward massive change. Part of this change is that we have moved from the industrial age to the information age. A consequence of this is information overload, which encourages more simplistic narratives in order to cope with the hyper-connected world we now live within. This has led to a very binary understanding of things – ‘good’, ‘bad’, ‘like’, ‘dislike’- you get the picture.

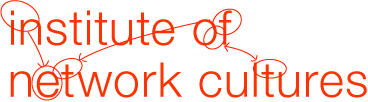

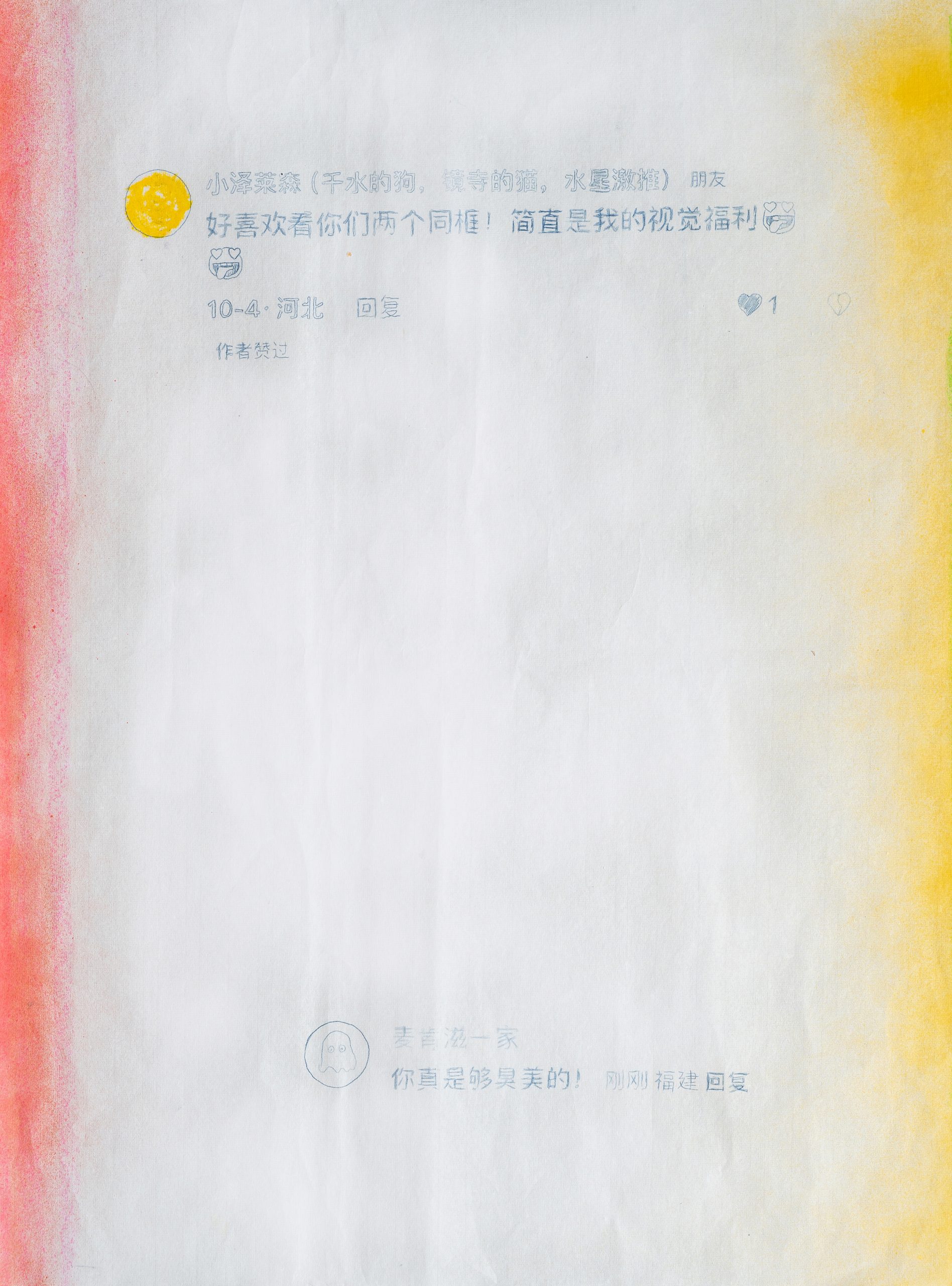

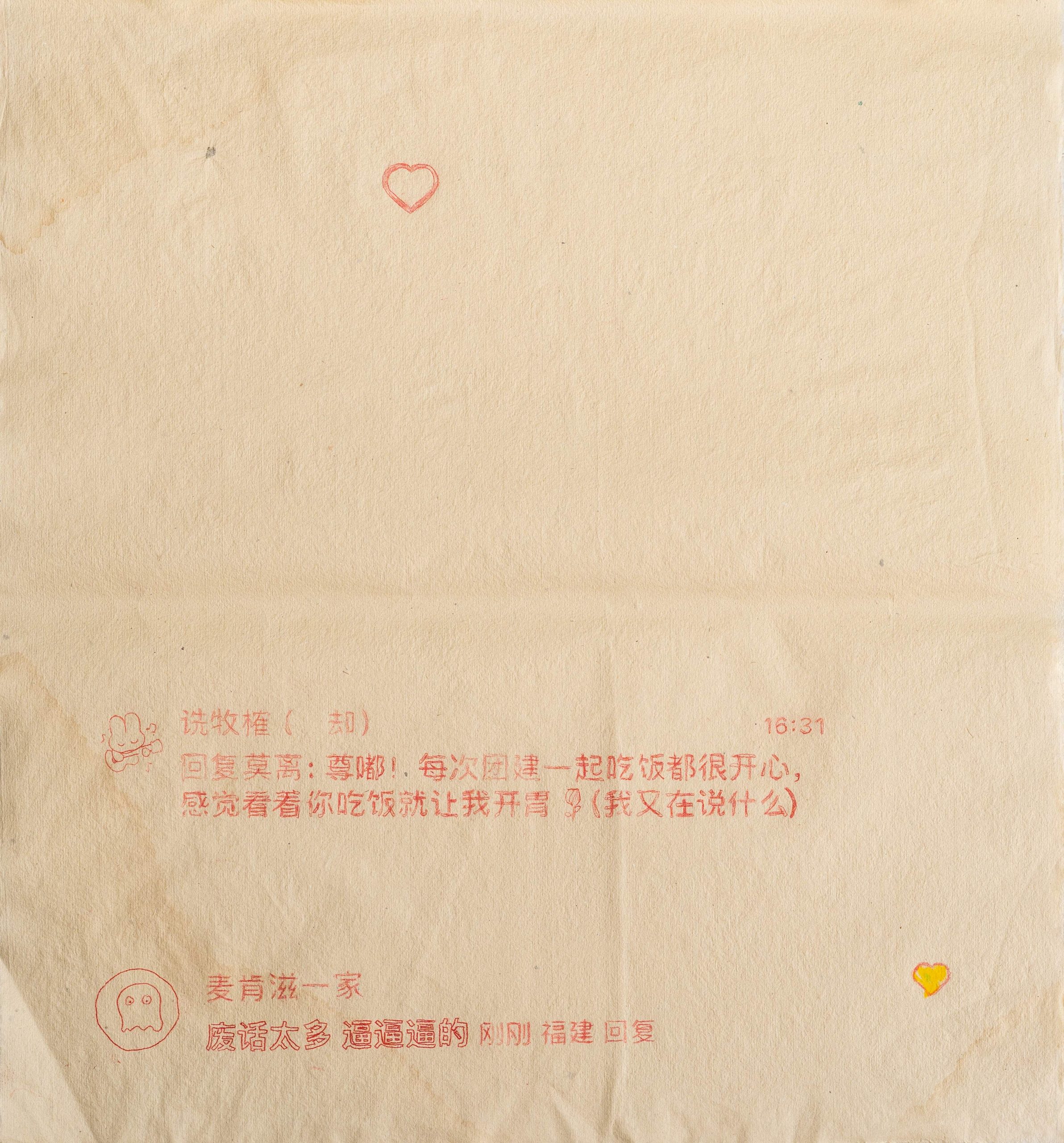

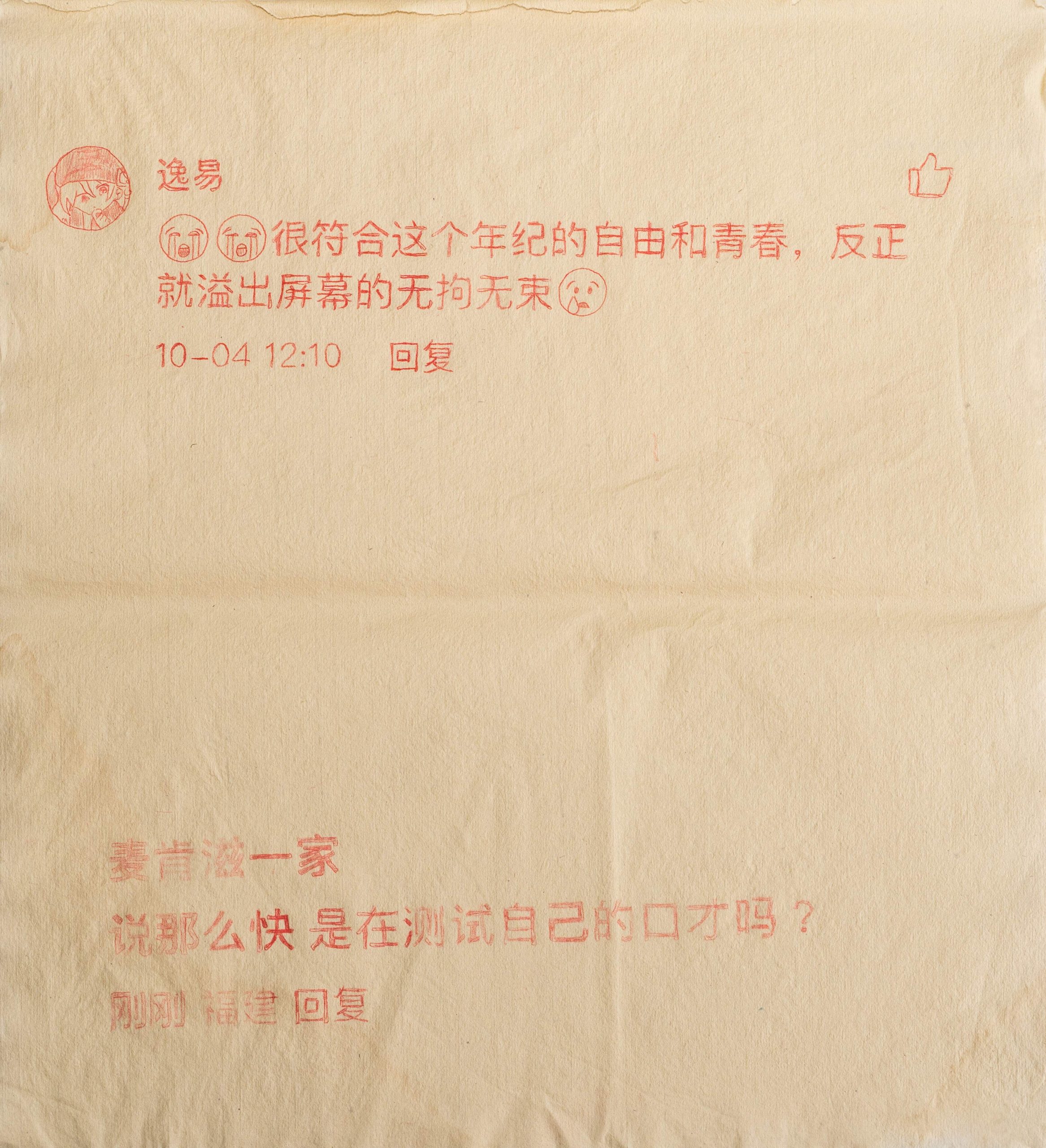

I created an art exhibition entitled: COMMENTS: Declaration of Love / Campaign of Hate as an artistic response to the binary nature of much online discourse. As I currently live in China, this project engaged with the Chinese online spaces people inhabit. The process of creating this work began with buying online comments, which I refer to as ‘online artefacts’[1], from students of the university that I was working in at the time, as well as the local Xiamen art community. I then appropriated and recontextualised those online comments that were either praising or abusive into physical text drawings.

The initial inspiration for this project came from an online activist named Alberto Escorcia. He views the Internet as a war between ‘love’ and ‘fear’[2]. Alberto researched how messages via social media platforms travelled between individual users during successful protests. What he discovered was that protests grew in size when online communication increased, which formed multiple inter-connection between masses of people – what computer scientists know as ‘capillarity’. Escorcia noticed that certain words used by online users in their communications increased the inter-connections between individuals and the online groups they associate with which powered the capillarity. He realised that if he knew in advance which subjects brought people together, and which strengthened the interconnections, he would be able to ‘summon up’ protests[3].

Escorcia’s understanding of how to get people’s attention can also be applied to capitalist agendas on social media. Some users on social media will post certain words or discuss particular subjects that they know will instigate attention. They are also powering ‘capillarity’, but instead of bringing people together to protest, the agenda is usually a ploy to instigate attention so that they can then turn that attention into social capital through likes, acquiring subscribers or garnering comments. This attention then can be transformed into financial capital as it proves this person has some form of influence or can get people talking, viewing products or propagating ideas. This is sometime done through love, which I propose are the online posts that instigate positive comments, or fear/hate, which are online posts that purposely ‘trigger’ people’s anger or resentment. In the neo-liberal structures of social media, love and fear/hate are both commodities to be exploited by both the users and the corporations that own the social media platforms.

The text drawings and paintings conceptually replicate the neo-liberal structures of social media. For this project, I capitalise on the emotions of love and hate that are expressed online. Exhibited within a gallery context in which the drawings are for sale, this conceptual choice replicates the way online content can be transformed into financial capital, first to the participants (as I bought the comments), second by commodifying the artwork (through the sale of the drawings). The creation of the artwork and the context of the exhibition conceptually engage with the economic structures of social media that profit off online communication.

Today’s version of capitalism no longer requires the creation of a traditional marketplace: it is simply the infrastructure upon which, say, users on social media interact[4]. Rather than dematerialising the routinised labour of an industrial age, in todays’ technology revolution, labour has been reconfigured in the form of ‘playbour’[5]. Although many of us view time spent on social media as a form of leisure or fun, it is a form of labour. Online labour itself becomes ever more fragmented and concealed as the act of engaging in social media conceals productive labour behind the veil of play. Using social media has become a daily activity due to how technology has become entrenched in society as a whole, particularly in China, as the country at this time is developing at a faster rate than any other in the history of humanity.

This text drawings are essentially a documentation of personal data that has been exploited and commodified by the participants of the project and myself as the artist to illustrate how the structures of social media exploit and profit off the current battle between love and hate that is being fought on social media. Data is today considered a valuable resource of the 21st century and a new type of raw material that’s on par with capital and labour[6]. Large-scale data processing is increasingly considered the defining feature of contemporary economy and society and the collection of data has become the new social and economic structure of a new ‘data-fied social world’[7].

Another inspiration for this project is my interest in the phenomenon of online self-disclosure. When people self-disclose, it usually encourages others to disclose personal information in response, which in turn encourages the user to disclose more, and so on. Today, many people perceive self-disclosure to be more intimate when it is received online than when it is received face-to-face[8]. To elaborate, I’m fascinated with online content that communicates human emotions in the flat existence of the Internet. When people self-disclose or express emotions on the Internet it both connects people emotionally yet also dehumanises the emotional communication or connection into a digital representation or imitation (simulacra) – the flat existence I was referring to earlier.

Online comments sections usually get active when people express or disclose something about themselves, or the political, cultural or social values they believe in. The term ‘keyboard warrior’ is commonly thrown around when people direct an opinion or accusation at a person or group on the Internet that they generally wouldn’t if they were confronting them IRL. For many people, being behind the safety of their computer screen or phone enables them to express themselves with less restraint and fear of disapproval from others. This is because the Internet allows elements of freedom in a sense that the normal consequences through physical social interactions are eradicated as a person can leave the interaction at any time and never come in contact with the other person involved again if they don’t want to[9]. Viewing the negative online comments in the form of text drawings in this exhibition, viewers may ask themselves if they would say these same things to a person face-to-face? Is there a difference if something is communicated online or offline? Does it matter? By extracting authorship and the original context of the online comments, the text drawings encourage viewers to question the social world that the structures of social media have created for us all.

It could be argued that expressing opinions and judgements, affirmations and insults, in online comments sections is a form of identity work. This is because understanding and constructing self is an emergent, dynamic process that must be understood within a community in which you interacting with others. This is because a self only achieves its central existence in situated activity[10]. Based on this argument, online comments sections are therefore spaces for self-representation where, through consistent and sustained actions and social interactions, people are able to assume certain social roles and shapes that align how they want to be perceived within their social network[11].

I propose that posting online comments are acts of (digital) mark-making[12] and a form of proof-of-presence. It is a declaration of a person’s existence and desire to be ‘part of the conversation’. We use social media to let the wider world know who we are through the online content we produce, which includes online comments. The aesthetic choice to materialise the online comments into analogue text drawings encourages viewers to engage in the works as examples of mark-making. A mark created by an individual is unique to its author, an expressive representation of self, evident from thousand-year-old cave-paintings to present-day signatures required on corporate documents.

These text drawings and paintings responds to the notion that our ‘real’ lives are ‘virtual’ lives have become ‘co-articulated’[13], meaning the online and offline worlds we inhabit have merged. Today, our so-called online selves, the person that is represented on our social media accounts, is not an avatar but an extension of our ‘real’ selves. I say this because notions of identity have changed. In the 20th century, self was fixed and singular, with the idea that we discover our understanding of true self from within. Today, self is fluid and multiple, and we somewhat construct self externally through online performance – the social media content we create.

This body of work asks viewers to look at ‘online content’ from a different lens. And the larger question I am exploring is: what does the online content that people post say about their desire to emotionally connect with others in today’s digitally hyper-connected landscape? This exhibition of text drawings and portraits continues my ongoing exploration of artistically representing human lived-experience that is both virtual and real.

—

[1] Mackenzie M. (2022), I Tweet Therefore I Am [Doctoral Thesis, Victoria University, Melbourne, Australia].

[2] Pomerantsev, P (2019), This is NOT propaganda: Adventures in the war against reality, Hachette, UK.

[3] Ibid

[4] Srnicek, N 2017, Platform Capitalism, Polity Press, Cambridge.

[5] Scholz T (2013). Digital Labor: The Internet as Playground and Factory. New York: Routledge.

[6] World Economic Forum 2012, ‘The global information technology report 2012’, Report, http://www3.weforum.org/docs/Global_IT_Report_2012.pdf.

[7] Couldry, N. and Yu, J., 2018. Deconstructing datafication’s brave new world. New Media & Society, 20(12), pp.4473-4491.

[8] Jiang, L. C., Bazarova, N. N., & Hancock, J. T. (2013). From perception to behavior: Disclosure reciprocity and the intensification of intimacy in computer-mediated communication. Communication Research, 40, 125e143. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1177/0093650211405313.

[9] Roesler C. (2008), ‘The self in cyberspace: Identity formation in postmodern societies and Jung’s Self as an objective psyche’, Journal of Analytical Psychology, Vol. 53, No. 3, pp. 421 – 436.

[10] Blumer, H 1969, Symbolic interactionism; Perspective and Method, University of California Press.

[11] Kaplan, A M & Haenlein, M 2010, ‘Users of the World, Unite! The Challenges and Opportunities of Social Media’, Business Horizons, vol. 53, no.1, pp. 59-68.

[12] Mackenzie M. (2024), ‘Curated Content: an exploration of the act of (digital) mark-making in the form of analogue drawings’, Telematics and Informatics Reports, Vol. 14, ISSN 2772-5030, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.teler.2024.100144.

[13] Leander, K & McKim, K 2003, ‘Tracing the Everyday “Sitings” of Adolescents on the Internet: A Strategic Adaptation of Ethnography across Online and Offline Spaces’, Education, Communication and Information, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 211-40.

—

Dr Michael Mackenzie works at the Xi’an Jiaotong Liverpool University within the School of Film and Television Arts. He is an academic, writer, filmmaker, and multi-disciplinary artist who is interested in creatively responding to what it means to exist in a world that we now experience as both virtual and real. If you are interested in contacting him or collaborating you can contact him at michael.mackenzie@xjtlu.edu.cn.