Florian Cramer announced the soon-to-be-released Digital Publishing Toolkit – the results of a two year project with publishers and designers that taps into their practical experiences and difficulties in developing a number of pilot e-book projects. It furthermore addresses ways in which publishers can change their internal ways of working so that releasing one publication simultaneously for print, web, epub and other formats becomes less painful and more efficient.

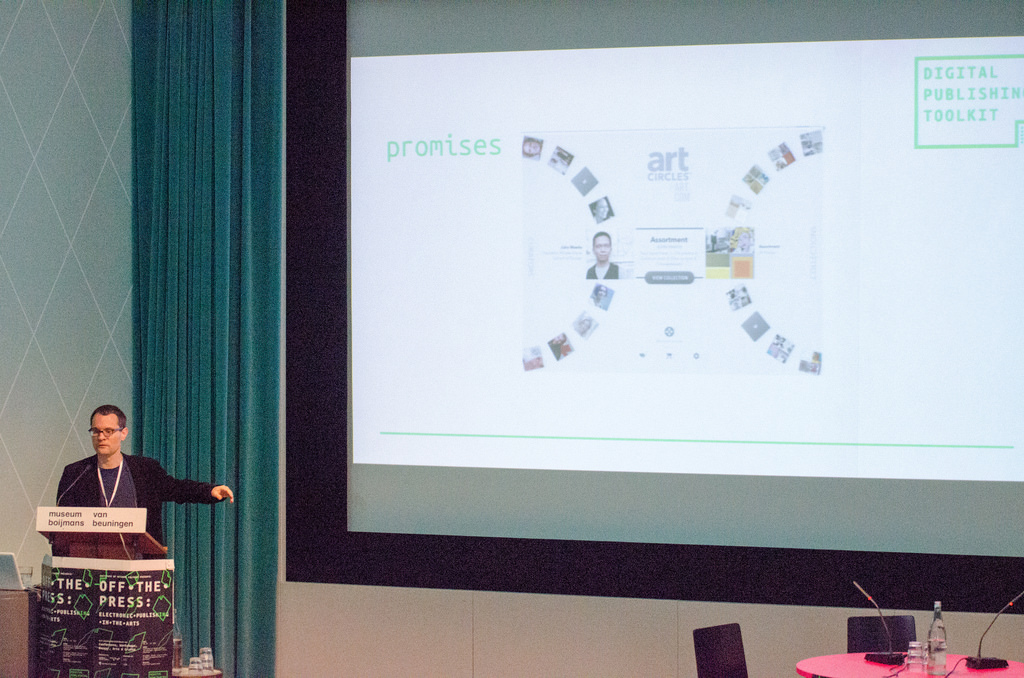

According to Cramer, digital publishing promised writers, designers and publishers exceptional visuals and interactivity combined with easy distribution and low costs. Examples such as Art Circle – an impressive application that brings entire art collections to readers via beautiful visuals, sound and interactivity – support this ideal.

photo credits: Martin Risseeuw

photo credits: Martin Risseeuw

So what isn’t currently working in e-publishing? Reality is, argues Cramer, that most arts and design publishers are small, have low budgets and can not maintain electronic publications that will continuous technical updates. Developing interactive applications would require those publishers to effectively become indie game designers – which is not workable in a world where books appear in editions between 500 and 1500. To complicate things, digital publishing is still a market in development. Print book publishing is in a deep crisis (for example, Rotterdam’s biggest – and only remaining general – bookstore recently went into bankruptcy) while there is no real mass market for e-books yet in continental Europe and the Netherlands. What publishers need is sustainable forms of electronic publishing. What is first needed, he says, is identification of exact needs. During the Digital Publishing Toolkit project, Cramer identified the following needs are: platform independence (the possibility to easily publish content everywhere – phone, tablet, PC, e-readers), stable formats, and optimized workflows that simplify the production process.

There are some important choices to be made in e-publishing, Cramer argued. One example are publishers who want to publish work as e-books that should better be on the web – but their only reason for choosing the e-book format is that they haven’t figured out how to monetize web content. In such cases, e-books and the ePub format are pseudo-solutions to problems that really lie elsewhere. In other cases, one should not underestimate the importance of offline reading. You can’t even read an online electronic publication in the high speed train from Amsterdam to Rotterdam with its many tunnels and connectivity disruptions.

Finally, when wanting rich material (audio, video, interactive), this will inevitably result in big files that may create unrealistic needs for mobile download bandwidth and storage on mobile devices. Multimedia interactivity furthermore creates challenges for compatibility to future devices and therefore technical maintenance. Therefore, one has to make a principle choice between simple flat text e-pubs best suited to e-readers and requiring practically no future updates, versus rich content that works best on tablets and mobile phones. In between the two extremes of flat text in the old epub 2 format and platform-specific applications (for iOS or for Android), there are also in-between options such as the more interactive and multimedia capable epub 3, Apple’s iBooks (an extended proprietary variant of epub 3) and apps written in HTML5.

Some practical issues were brought forth as well. One is the support of the epub standard on e-readers and e-reading software. It is currently as bad and as inconsistent as the support of web standards in the web browsers of the 1990s. Another issue is that software workflows in the editorial process need rethinking. (Cramer mentioned the Microsoft/Adobe legacy as unworkable). The technically ideal solution is the document format XML as a basis from which documents can be automatically translated into desktop publishing files, web pages and e-books, but in most cases, XML is too complex and technically demanded for non-IT companies. A pragmatic solution is to use simplified document markup languages like MultiMarkdown, which are easy to write and read, and a good basis for automatic file format conversions, too. Unlike HTML, which could also be used for this purpose, MultiMarkdown has an unambiguous syntax that can’t easily lead to incompatibilities when several people have worked on the same file.

Cramer further discussed costs, a rather sensitive aspect: “the promise that the electronic publishing is cheaper is a false promise”, he argues. That is why it becomes important to optimize workflows in the production process.

Ending his talk, Cramer has an important question for the audience: why do publishers tend to stick to the traditional formats of publishing even when they move to e-publishing? He gave the example of poetry books. Traditionally, poetry is published as poetry volumes because it is the only economical way of printing, distributing and selling it. With e-publishing however, it is possible to sell single poems. The same is true for exhibition catalogues. He gave the recent example of Stedelijk Museum, the Dutch contemporary art museum. It would have made no sense to publish its 200-page collection highlights catalogue as one e-book. But e-publishing makes it possible to turn each monographic chapter on an individual artwork into a mini-epub of its own, and to allow readers to choose what they want to explore and read.

The same essential questioning of formats concerns anthologies and periodicals. Cramer gave the example of the Dutch contemporary art and theory magazine Open which successfully transformed from a print periodical into a web platform. The overall point here is that traditional publishing formats often don’t follow some necessity dictated by their content, but rather the technical necessities of print production, distribution and retail. Since e-publishing obsoletes many of these necessities, it urges publishers to rethink those basic formats – rather than simply making books with multimedia additions.

You can find a PDF of his original presentation here: Presentation Florian Cramer

Florian Cramer is a reader for new media in art and design at Hogeschool Rotterdam, and director of the Creating 010 centre for practice-oriented research in support of creative professions. He also is dean of the Parallel University of WORM, the Rotterdam-based Institute of Avantgardistic Recreation. Last publication: Anti-Media, NAi Publishers, 2013; What Is Post-Digital?, A Peer-Review Journal About, 2014.