‘The old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born;

now is the time of monsters’ – Antonio Gramsci

Over the past decade, the Institute of Network Cultures has led several applied research projects about new (digital) publishing models: the Hybrid Publishing Toolkit, Urgent Publishing and Going Hybrid. Time and again, publishers, designers, coders, authors, and readers bring up the same problem: the ‘book publishing industry’ fails to fulfill the promise of a rich multi-media reading experience in the digital era. Many digital tools for publishing experiments remain marginal, while traditional publishers and big tech platforms shy away from new formats. Audio and video integration — technically possible for a good three decades — is all but absent. Book sales keep decreasing. Young people read less and less, both online and offline. All in all, it becomes increasingly harder to sustain indy and experimental publishing practices while the regressive gap between so-called real paper books and the ‘virtual’ social media swiping keeps growing. Gutenberg the Second, where are you now that we need you?

To address this challenge head-on, we brought together a group of ‘expanded’ (small, independent, experimental, multimedia) publishers and developers to figure out together if there are any prospects of sustainable change. This effort was aligned with the Creative Europe project we are currently spearheading, but in this case, we worked with partners in the Netherlands: Hackers & Designers, Archival Consciousness, Lukas Engelhardt, Amateur Cities, the publishers Valiz, StarFish, Spookstad and HumDrumPress, APRIA, The Hmm, Sandberg Institute (MA Design), and the Piet Zwart Institute. We wrote a two-year funding application entitled Expanded Publishing: Not Yet Another Tool to create a platform to both archive and develop publishing innovations: publishing software, workflows and economic models.

Our RAAK (Dutch applied science) application was rejected in August 2024. The fact that we worked with small organisations gave the commission too little confidence that we could create a “significant market impact”. We sharply protest against this decision. Of course, we remain convinced of the urgency of our project, and we stay involved in expanded publishing experiments. The text below is made up of relevant bits of content that we evacuated from the application document. (This was the work of a team of four during five months. The preparatory phase of a RAAK application is a long and complex one, as the Dutch funding organization requires surveys, interviews and meetings that will have to be written down and integrated into the application to prove that there is enough demand in the professional field for the proposed research question and approach. Unlike academic research conducted at universities, the applied science establishment in NL requires professionals to first express the research question, which is then ‘picked up’ by the poly-tech researchers — a well-intended but slightly dubious bureaucratic procedure, as it never quite works like that.)

The entanglements of (publishing) infrastructure

Now, over to the actual matter. With the advent of personal computers and the internet in the 1990s, the promise of a rich multimedia reading experience was born. A world of possibilities opened: moving images in books, 3D reading environments, interactive storytelling, and many more innovations seemed to be within reach. But three decades later, we are still reading scanned PDFs from the traditional book. Major Dutch publishing houses focus exclusively on print and occasional ePubs, and distribution is monopolised by big tech platforms like Bol.com and Amazon. In the meantime, the market is getting more challenging as the attention economy reshapes readership and literacy, and Generative Artificial Intelligence is starting to occupy the positions of writers and editors. Where did the promised boom of multimedia books — and, with it, the advent of a new reading culture — go wrong?

Fragmented and Repetitive Innovations

Book innovations hardly get off the ground due to two developments in the market. Following the rise of e-books, tablets and audiobooks more than 10 years ago, the traditional book market has ‘consolidated’. There is little room for new players, and traditional publishers in the Netherlands, such as De Bezige Bij, Prometheus and Atlas Contact, are risk-averse. According to David Huijzer, editor-in-chief of INCT.nl, a professional journal for publishers in the Netherlands, the absence of rich multimedia reading experiences has largely to do with the structure of the publishing industry. Huijzer: “Would it be possible to share content differently? Yes. Should we? Yes. But publishers are hesitant. The industry doesn’t like avant-gardism.” In Huijzer’s view, this has to do with a lack of an ‘early majority’ public for multimedia products and crossovers. He observes that “it’s not easy to find people who want to experiment, especially in the for-profit domain. You won’t be seeing commercial market disruptors any time soon.” In addition, international platform companies play an increasing role in the book industry. Amazon, Kobo and Storytel are blurring the lines between sales, distribution and subscription services. They have innovative power but put business profits before social interest. Therefore, the innovations of these platform companies get stuck in a trendy new app or gadget without depth. Publisher, educator, and designer Niels Schrader perfectly summarized the collective pickle of expanded publishing in the context of platform capitalism: “We need to address agency, money, and platforms. As publishers, we’ve gained more platforms, but at the same time lost agency.”

Fortunately, the consolidated market is by no means indicative of an absence of publishing experiments. Many small, innovative publishers have developed tools and practices to expand their publishing practice. We have defined this as ‘expanded publishing’ (sometimes referred to as ‘self-reflective, extended, hybrid, experimental or urgent publishing): the development of alternative methods (both technological and social) and formats alongside traditional ones, creating a dynamic creative, multi-medium and accessible process and output. Examples of these expanded forms include video essays, interactive comic books, podcasts, real-time event reports, live virtual exhibitions, collaborative digital archives of the past, present, and future, as well as yet-to-be-defined formats. Other authors and projects also refer to ‘expanded publishing’ as “a practice in which books and screen-based texts are considered part of a process which includes talks, exhibitions, performances and software development”. Valiz co-directors Astrid Vorstermans and Pia Pol, in an interview with Amsterdam Alternative, describe how they want to bring their traditional book publishing business into experimental paths:

We have been thinking of ways to approach content in a new light, creating a different platform. For example, we have been doing many events, lectures, and performances, which tend to take a secondary space, always sort of squeezed between our other projects. But what if we looked at them differently? As an entity in and of itself? What would that need, and how could we position it in a way that is unique to us? How do we make this content available in a different format, a different medium than the book? We have also been thinking about becoming a more nomadic platform, one that would meet with people to talk about projects and bring our specific knowledge to them.

While people remain committed to experimental, risky publishing because of the added cultural and social value, we also know that it is not easy to make time and free up energy for this kind of question in daily practice. Expanded publishers are bogged down by practical problems, such as high workloads, increasing power of big players and technical hurdles. Mainstream research platforms hope that disruptive innovation might still be possible. “How do you free up the resources for that game-changing innovation? This is a split that characterizes all companies that want to innovate in the consolidated book market,” according to knowledge platform KVB Boekwerk. Our take is very different; we don’t expect innovation to solve the economic precarity of expanded publishers. The innovation cycle is the very core of the problem, with workload-intensive ‘innovations’ being half-developed, discarded, and left behind at an increasingly rapid pace. Rotterdam-based publisher and researcher Florian Cramer also asks: “How do we avoid reinventing existing best practices and make platform alternatives sustainable?” Among the expanded publishers we spoke to, we found a large shared interest in finding economic sustainability by sharing resources, scaling up collectively, and creating a more equitable tool ecology.

Due to a lack of knowledge and resource sharing, innovations in the publishing industry remain stuck in a cycle of reinventing the wheel. Publishers especially lack insight into existing innovations. “Under the day-to-day workload, it is not easy to invest time in (new ways of) experimental publishing,” said publisher Pia Pol. Out of convenience, they use user-friendly services on big tech platforms, although sharing open-source software horizontally is closer to their mission and ideals: “Sharing knowledge and resources is perhaps even more important than developing new software”. Publishing software developers are also often unaware of the work of their colleagues, leading to unnecessary repetition of innovations. For example, four software developers within this consortium independently developed software solutions for converting a website into a book. In short, both expanded publishers and software developers need more insight into existing innovations.

Open-source software known to partners is often technically demanding, unstable and time-consuming, says publisher Amy Gowen, “We find it difficult to learn to use an open-source version of Google Docs. If we have to give a crash course to our collaboration partners, it becomes completely difficult”. Marianna Lanari points out that this situation is the result of thinking and working too project-based: “We need to figure out what a healthy ‘social economy’ of publishing software looks like. We often develop software with project funding, but how do we make these tools sustainable for the long term?” To create a more resilient book industry, partners indicate, software solutions and other resources must be scaled up collectively.

Expanded publishers are struggling to find revenue and governance models that can support expanded publishing over the long term. “I don’t know of one sustainable model,” software developer Karl Moubarak shares. As a result, innovative publications often remain one-time experiments, and budgetary considerations lead to content concessions. Spookstad publisher and designer Lukas Engelhardt puts this tension into words: “How can you professionalize and become more sustainable while remaining close to social commitments?”

“Catching Up in the Archive”, De Appel, 2022

At the same time, the growth of open-source software from independent players such as the Coko Foundation, stimulated by government policy, shows that a shared understanding of existing innovations can be obtained — within the field of expanded publishers, a range of platforms for open-source sharing of publishing software has been created over the past fifteen years. Good examples are the Flemish-Dutch PrePostPrint, the repository of Brussels-based Open Source Publishing, and the products of Coko Foundation: Transforming Publishing and the Coop Cloud Federation. Examples from academia include The Library of Artistic Print on Demand, developed by the University of Nuremberg, Silvio Lorusso’s Post-Digital Publishing Archive, our own Digital Publishing Toolkit, the Experimental Publishing Wiki of the Piet Zwart Institute in Rotterdam and the Open Publishing Compendium from the UK.

While each of these platforms houses valuable knowledge, not one is a shared, sustainably used resource maintained by a strong network of publishers and software developers. The Post-Digital Publishing Archive, for example, as it became clear in a conversation with Lorusso, is primarily a solo project and lacks a participatory component — what started as PhD project thriving in the academic setting faced the precarity of resources in the professional field. Innovation platforms in the Netherlands that work well in that sense, such as KVB Boekwerk, are rooted in the traditional book industry and thus lack precisely the state-of-the-art innovation of expanded publishers and their software developers. This situation shows that there is currently a lack of thorough understanding of the kind of digital platforms that a strong network of expanded publishers and publishing software developers needs for sustainable sharing and scaling of knowledge, insight and innovations.

Internationally, there are several relevant practices that serve as sources of inspiration. Thee include Cube Commons from Canada, Aarhus University’s ServPub program and the German Cosyll, publishing art education materials, minor publications and syllabi, respectively, using a well-developed digital platform, blockchain technology and a strong social network. Another important source of inspiration for the consortium is Wikipedia, described in Joseph Reagle’s Good Faith Collaboration: The Culture of Wikipedia as an example of a platform rooted in the principles of open collaboration and illustrates how different contributors come together to build a vast body of knowledge.

Social and Technological Protocols

Inaccessible or unstable software hinders the adoption and development of existing tools into new contexts, and publishers fail to integrate technological innovations into their workflow. Without the necessary social and technical protocols, such as manuals, licenses, source codes, public ‘repositories’, and other forms of user agreements necessary to provide transparent access to shared resources, the threshold becomes too high. In the context of expanded publishing, we explore the techno-social dynamics needed for sustainable workflows, and open-source communities often make good use of social protocols. An obvious example is the social medium Mastodon, which operates similarly to X (formerly known as Twitter) but runs on self-hosted servers maintained by the community. As a nonprofit and open-source social medium, Mastodon allows users to access the platform’s underlying infrastructure and algorithms, avoiding privacy-violating surveillance techniques. A good, effective balance of social and technical protocols, as with Mastodon, is what Star and Ruhleder describe as “an ecology of infrastructure for large information spaces”. In contrast, a lack of effective protocols – currently visible at X – creates what Freeman called “the tyranny of structurelessness”.

In the domain of (post-)digital publishing, three movements have determined the developments of social and technical protocols. The first is the legal development of Creative Commons licensing through the “copyleft” movement, which enshrined copyright as a community asset in the public domain. Second, making good use cases and storing open source code in public “repositories” has become the norm in open source communities through the Free/Libre Open Source Software (FLOSS) movement, which has been working for an open and democratic Internet since the 1990s. The most recent development in social and technical protocols is the emergence of blockchain technology, which captures the online space for social interactions, decision-making and transactions in transparent codes. Blockchain is often deployed by DAOs (Decentralized Autonomous Organizations) and used for publishing digital cultural expressions in the form of NFTs.

Publication in Ethertoff, ready for print mode

So, while there is a lot of focus in open-source communities on the techno-social aspect of resource sharing, expanded publishers who are part of this community are not yet succeeding in sharing publishing software in a long-term and stable manner. The reason for this is not known, and there needs to be further research into why existing protocols for sharing open-source software do not (yet) work for expanded publishers and how protocols that do work can be developed.

Governance and Ownership

As we expected, we found that economic uncertainty holds back innovation and digitisation within the consolidated book market, and the focus is shifting from print books to digital platforms and e-books, audiobooks and podcasts. An important factor here is that it is not the local publishers but the international platform monopolies (Amazon, Google, Lulu, Storytel) that take advantage of new models such as self-publishing, e-book subscriptions, freemium content, crowdfunding and algorithmic curation. Media field experts call upon structural changes in business plans and collaboration strategies to develop a resilient publishing industry — and independent publishers must be the ones spearheading it. This can build on existing best practices, such as the “co-publishing model” in which writer and publisher share financial risk, the “small press model” described by Cutts (with printing coalitions and independent book exchanges, among others), the membership model of the Open Book Collective, and the cost-effective employee cooperative model as used by publishing software developer Autonomic Cooperative.

These best practices show that operationalizing innovative revenue models is closely related to choosing matching governance and decision-making models, such as cooperatives. In this context, alternative governance models emerge as crucial components for promoting resilience and sustainable innovation. According to Ostrom, the management of shared resources (‘commons’), a concept applicable to the collaborative nature of publishing networks, relies on principles such as collective decision-making and shared responsibility. The idea of commons-based peer production in the digital domain, as proposed by Benkler, aligns with the ethos of collaborative networks and emphasizes the decentralized creation and management of resources. In the field of governance and operations for expanded publishers, in short, there is no lack of models to follow and add to. However, we need to continue to research which of these many models could work for expanded publishing.

Expanded Publishing in Practice: Etherport

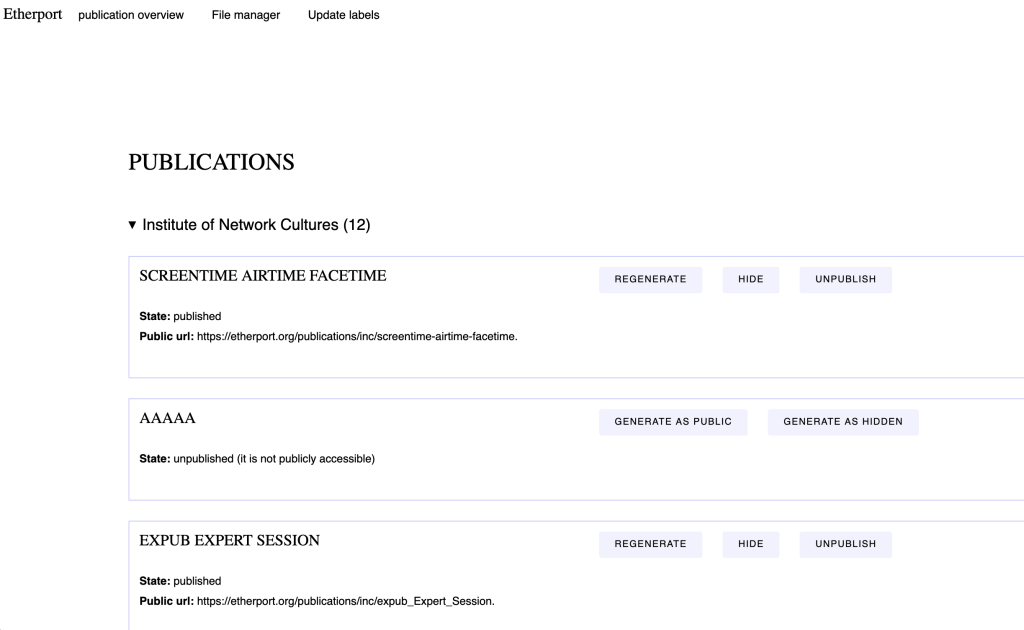

In our own experiences with expanded publishing (named at the beginning, but going beyond), we have put (expanded) publishing as a crucial part of our projects, building tools and methods. While the concept of “Not Yet Another Tool” was to establish a model that could become sustainable beyond the project-tool timeline, we have started to develop experiments in platform-independent writing, designing and publishing through Etherport. Etherport is based on the tool patchwork Ethertoff, which includes Etherpad (text editor), Django (framework), and Paged.js (paged media polyfill): it was developed together with Gijs de Hij at Open Source Publishing, in the context of the research project Going Hybrid and we continue to work with it. What started as a place to develop event reporting in new ways, rethinking notions of presence, archiving, and linearity, is now a publishing tool which allows us to think about form and content at the same time. We invite you to explore Etherport more here.

Etherport on the backend

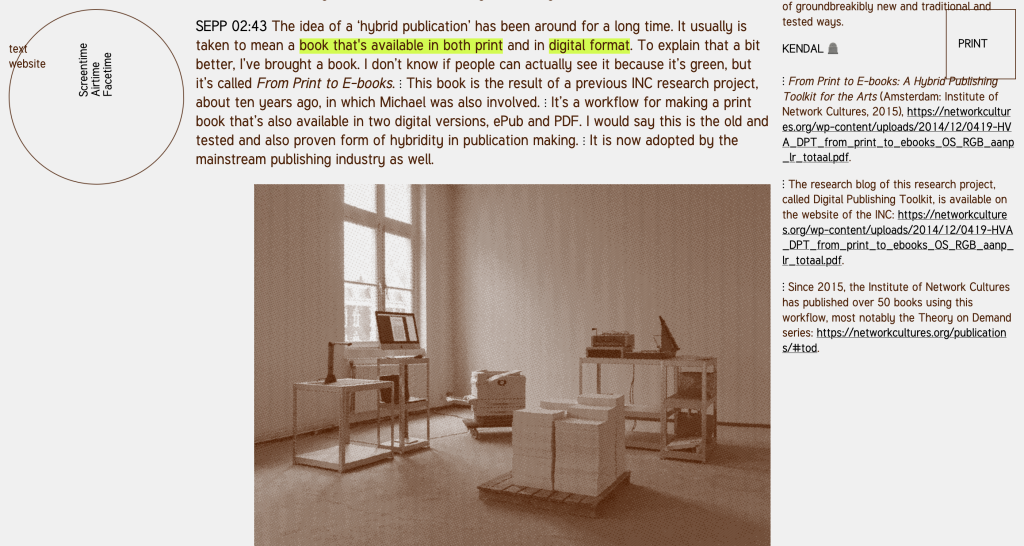

“Screentime Airtime Facetime”, 2024

The new dynamics and roles that Etherport challenges, both in relationships writer-editor-developer-designer and reader-maker, offer new possibilities for innovation, protocols and governance. It also expands notions of “medium” since it allows for multimedia publishing and toggling between web and print formats without being simply a pdf on a screen. So far, we have published Screentime Airtime Facetime, which used Etherport for its editing and designing. We will continue to develop it as a new iteration of the tool comes with a new publication — not just technical iterations, but social networks that are built and new readerships that can be formed. This does not come without its challenges: we still need to build more sustainable maintenance and work on some accessibility features, although that threshold becomes smaller with each iteration. The gaps that we have identified in this post still need further research so that Etherport becomes not yet another tool but an embodiment of expanded publishing that challenges the traditional book.

Literature

Arkenbout, Chloë, ‘Challenging Oppressive Discourses in the Digital Public Sphere: Reflections on Anger and Empathy in Comment Wars’, Institute of Network Cultures, 22 December 2022, https://networkcultures.org/longform/2022/12/22/challenging-oppressive-discourses-in-the-digital-public- sphere-reflections-on-anger-and-empathy-in-comment-wars/.

Baldwin, Carliss en Jason Woodard, ‘The Architecture of Platforms: A Unified View’, Platforms, Markets and Innovations, 2008.

Benkler, Yochai, The Wealth of Networks: How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006).

Bille, Paul, Lukas Engelhardt, and Ada Reinthal, A Self Hosting Manual (Amsterdam: 2022).

Campagna, Tommaso, ‘Blurring the Format: Expanded Publishing for Practice-based Research’, Institute of Network Cultures, 7 February 2023.

Catlow, Ruth and Penny Rafferty (eds.), Radical Friends: Decentralised Autonomous Oragnisations and the Arts (Londen: Torque Editions, 2022).

Carillo, Kevin, Sid Huff, and Brenda Chawner, ‘It’s Not Only about Writing Code: An Investigation of the Notion of Citizenship Behaviors in the Context of Free/Libre/Open Source Software Communities’, conference paper, 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Science.

Carillo, Kevin, Sid Huff, and Brenda Chawner, ‘What Makes a Good Contributor? Understanding Contributor Behavior within Large Free/Open Source Software Projects – A Socialization Perspective’, Journal of Strategic Information Systems, vol. 26, no. 4, 2017, pp. 322-359.

Coding Bodies (Amsterdam: Hackers & Designers, 2020).

Cramer, Florian, ‘What Is Urgent Publishing?’, in APRIA – ArtEZ Platform for Research Interventions of the Arts, vol. 1, no. 1, 2021, https://apria.artez.nl/what-is-urgent-publishing/.

Cramer, Florian, ‘Hybrid Publishing: Between Print and Electronics, Art and Research’, in Imagining Alternative Futures (Rotterdam: Rotterdam Arts & Science Lab, 2018), pp. 138-147.

Crean, Irene de (ed.) A Very Short and Incomplete Guide to Subversive Publishing Strategies (Amsterdam: Framer Framed, 2023).

Cutts, Simon, The Small Press Model (Glasgow: Uniform Books, 2023).

Dolata, Ulrich and Jan-Felix Schrape, ‘Platform Architectures: The Structuration of Platform Companies on the Internet’, Research Contributions to Organizational Sociology and Innovation Studies Discussion Paper, no. 1, 2022.

Eckenhaussen, Sepp (ed.) Minizine: Elements of the Conversation Starter (Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2023).

Eckenhaussen, Sepp, ‘Relevant Tools & Practices in Hybrid Publishing’, Going Hybrid, 3 October 2022, https://networkcultures.org/goinghybrid/2022/10/03/relevant-tools-practices-in-hybrid-publishing/.

Eckenhaussen, Sepp, ‘The Crowbar of Cultural Publishing: Introducing the Hybrid Publications Research Group‘, Institute of Network Cultures, 6 July 2023, https://networkcultures.org/goinghybrid/2022/07/06/the-crowbar-of-cultural-publishing-introducing-the-hybrid-publications-research-group/.

Eckenhaussen, Sepp a.o., ‘Introducing Etherport.org: A Publishing Tool for Cultural Event Reports’, in Sepp Eckenhaussen, Senka Milutinović, Carolina Valente Pinto, and Miriam Rasch (eds.), Screentime Airtime Facetime: Practicing Hybridity in the Cultural Field (Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2024), https://etherport.org/publications/inc/screentime-airtime-facetime/chapters/introducing-etherport.html.

‘Endogenous growth of open collaborative innovation communities: a supply-side perspective,’ Industrial and Corporate Change Advance Article, no. 4, 2018, pp. 1-762.

Fontein, Bas and Paül Herrera, Do/Don’t Do It Yourself: The DIY and DNDIY of 25 Years of Basboek (Apeldoorn: Basboek, 2023).

Gonzalez, J.M. and G. Robles, ‘Trends in Free, Libre, Open Source Software Communities: From Volunteers to Companies’, Information Technology, no. 5, 2013, 173-180.

Groten, Anja (ed.) First… Then, Repeat: Workshop Scripts in Practice (Amsterdam: Hackers & Designers, 2022).

Groten, Anja and Juliette Lizotte (eds.) Network Imaginaries (Amsterdam: Hackres & Designers, 2021).

Groten, Anja en Juliette Lizotte (eds.) On/Off the Grid (Amsterdam: Hackres & Designers, 2018).

Kircz, Joost, and Adriaan van der Weel (eds.), The Unbound Book (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2013).

‘KVB Boekwerk: kennis en innovatie’, KVB Boekwerk, accessed 12 December 2023, https://kvbboekwerk.nl/innovatie/kvb-boekwerk-kennis-en-innovatie.

Lerner, J. and J. Tirole, ‘Some Simple Economics of Open Source’, Journal of Industrial Economics, vol. 50, no. 2, 2002, pp. 197-234.

Lorusso, Silvio, Pia Pol, and Miriam Rasch (eds.) Here and Now? Explorations in Urgent Publishing (Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2022).

Lovink, Geert, Stuck on the Platform: Reclaiming the Internet (Amsterdam: Valiz, 2022).

Lovink, Geert, Zero Comments: Blogging and Critical Internet Culture (New York: Routledge, 2007).

Ludovico, Alessandro, Post-Digital Print: The Mutation of Publishing since 1894 (Eindhoven: Onomatopee, 2012).

Not Just a Collective (eds.), Survival Guide for Self-Publishers (Arnhem: 2023).

Ostrom, Elinor, Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action (New York:

Cambridge University Press, 1990).

Reagle Jr., Joseph M., Good Faith Collaboration: The Culture of Wikipedia (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2010).

Star, Susan Leigh and Karen Ruhleder, ‘Steps Toward an Ecology of Infrastructure: Design and Access for Large Information Spaces’, Information Systems Research, vol. 7, no. 1, 1996, pp. 111-134.

Valente Pinto, Carolina, All the Other Directions We Can Go: Alternative Media Networks and their Infrastructures (Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2023).

‘What Is Co-publishing?’, PublishDrive, no date, https://publishdrive.com/glossary-what-is-co-publishing.html.

Zoller, Rahel, The Inner Monologue of a Book (London: 2021).