(This interview, conducted via email in July 2018, appeared in the double issue, edited by Georgina Cojocaru, on ‘Art & Digitality’ of the Romanian art magazine Arta. The text below is the original ‘extended’ version. It happens to be that I have a special relationship with Revista Arta, going back to the early 1990s when I met the editor in Bucharest, Calin Dan and art historian/critic Magda Carneci (who editor of Arta right now), the Open Society Foundation, all facilitated by the Dutch rebel ambassador Coen Stork. I was involved in a special media art issue that appeared in late 1993, designed by Mieke Gerritzen, that coincided with the Ex Oriente Lux exhibition I co-organized.

Ceaușima: at the abandoned construction site of Bulevardul Uniiri, Bucharest, May 1991. Photo: Adolf Buitenhuis.

Georgina Cojocaru: What brought you to Mediamatic magazine in the late 80s? Was it the same time you decided to devote yourself to media theory? Was the magazine a place where you found yourself motivated to continue working in this field?

Geert Lovink: Late 1983 I lived in West-Berlin for a year, in the squat Potsdammerstrasse 130. There, I fully immersed myself for the first time with theory: philosophy, humanities, contemporary French thinking, away from political science, anarchism, Marxism, but also squatting and the social movements that I studied (and was a part of) at the University of Amsterdam, where I studied for six, turbulent years. Right before the move to Berlin I encountered Basjan van Stam and decided to join his one-man band, The Foundation for the Advancement of Illegal Knowledge (Adilkno in English, Bilwet in Dutch and German).

The following transitional period (1985-1987) was a harsh one for me. I was unemployed and the Amsterdam squatters movement was in decline. At the same time, the infrastructure we were building up was still expanding: theatres, bars and restaurants, free radio stations, printing presses, carpentry workshops, tool sharing, up to pirate TV experiments. And above all, autonomous free housing for many thousands of young people. It was an odd mix of crisis and care-free living. There was literary no future in this era of Reagan, Thatcher and austerities. Factories closed down, offices were downsizing and people moved out of Amsterdam in huge numbers. The 1980 slogan ‘The City’s Ours’ was not hubris. The balance between activism and theory shifted in 1987 when I decided to become an independent media theorist (whatever that meant). I had left the realm of social theory and my interest in art and aesthetics rapidly took over.

In 1987, Willem Velthoven and Jans Possel had moved their Mediamatic magazine, which started in 1985, from Groningen to Amsterdam. In 1988, they came across our writings and contacted us. Half a year later I joined the editorial team. Mediamatic started off as a video art magazine. In the mid-late 1980s video art was at its height in terms of institutional support and infrastructure such as festivals, editing facilities and rental facilities that worked on behalf of video artists. In the first years, the magazine mainly published reviews of new tapes, installations and festivals. In the early 1990s a broader editorial board was installed, that, besides the two founders, consisted of Paul Groot, Jorinde Seijdel, Dirk van Weelden, Maurice Nio and myself. Each issue had a theme such as The End of Advertising, No Panic, The 1/0 Issue, Radical Boredom, Storage Media or The Ear. Besides the one page speculative contributions of our Adilkno group (which were later on collected in The Media Archive), I started to review a lot of German media theory books. In this way, the rich material around Friedrich Kittler started to find a broader audience outside of academia, in the non-German reading world

My five or six years at Mediamatic were turbulent ones. The Berlin Wall came down, communism collapsed. Video arts got blown up because of the rise of the PC and multi-media. Analogue turned digital, the internet was introduced, and with it, the long goodbye of the dominant print and broadcasting paradigm of the ‘old media’. In that period I lived for a second time for a longer period in Berlin (90-91), went to California, Japan and India for the first time. I visited Romania for the first time in April 1990, which had a big impact on me. I then started to come back more regular from late 1991, staying for longer periods in Cluj and Bucharest. From 1994-97 I was partly based in Budapest. In 1992/93, the time when I left the dole and started earning my own money, I gave my very first classes in media theory and video art at the National Art Academy in Bucharest where I brought a lot of books, magazines and tapes.

Mediamatic magazine became famous because of the artistic CD-ROMs that started to be included. I left the editorial board late 1994, when Mediamatic had moved into a big office and was turning itself into a web design agency. Soon after I left, the printed edition was discontinued and Mediamatic continued as a website (which it still is to this day: www.mediamatic.net. The vehicle that moved Mediamatic into the business realm was the slightly New Age techno-optimist design conference series called Doors of Perception, produced together with John Thackera, who was then heading the Dutch Design Institute. I was no longer involved in either of these activities. In my opinion, Mediamatic should have been turned into the European alternative for Wired (and their Californian Ideology). In 1991-92 Mediamatic had close connections with the predecessor of Wired magazine, called Electric Word. Soon after Louis Rosetto moved his operation from Amsterdam to San Francisco to start Wired magazine there. Jules Marshall, who decided to stay in Amsterdam, joined Mediamatic. As most Mediamatic editors did not support my proposal to continue the magazine, I left and soon after started to work with Pit Schultz in Berlin where we founded nettime with the purpose in mind to work on a continental European answer to the Californian ideology. Already then the ideological agenda of Silicon Valley was becoming apparent, in part thanks to early American cyber critics such as Mark Dery, Clifford Stoll, Paulina Borsook, Critical Arts Ensemble and many others.

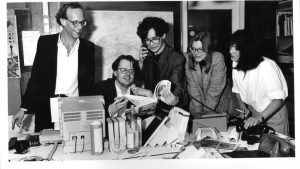

Mediamatic editorial team 1991/92, from left to right: Geert Lovink, Willem Velthoven, Maurice Nio, Jans Possel and Jorinde Seijdel.

Another reason to leave Mediamatic was the sudden rise of non-profit internet initiatives. Early 1994 we started the community access provider The Digital City (dds.nl) and a small office above the Bimhuis Jazz club called desk.nl, where artists could share unlimited internet access (at that time people still had expensive, slow access through a telephone modem. Late 1994, Caroline Nevejan (Paradiso) and Marleen Stikker (De Balie), with whom I both collaborated, founded Waag Society, which opened mid- 1995 in the oldest building of Amsterdam on Nieuwmarkt.

GC: You stated elsewhere that, although coming from a different background (i.e political science, social studies, activism), the encounter with contemporary art and new media art opened new horizons for you. Can you remember a particular work of art, an artist or an exhibition that left a long lasting impression on you or your work?

GL: I grew up behind the Amsterdam Concertgebouw. I regularly visited the Stedelijk Museum, De Appel and Fodor, but also squatted art spaces such as W139 and Galerie Amok. What caught my attention was the media art manifestation throughout town called Talking Back to the Media in 1985. This coincided with live video art events on the Amsterdam public access cable channel called SALTO. In particular the experiments of Rabotnik TV, as I was part of that scene through Franz Feigl, a key person at the time in the Amsterdam underground. His NL-Centrum was connected to groups such as Minus-Delta-T, Laibach and the Van Gogh TV crew. There isn’t much written yet about these underground movements. An exception I should mention is S. Alexander Reed’s brillant Assimilate, a Critical History of Industrial Music from 2013.

GC: What gave you an insight into the evolution of these new emerging practices, perhaps, as an anticipation of how things could go wrong? Nowadays, after the post-internet art hangover, there seems to be less of a hope left about the emancipatory possibilities of new media art, that has, lost some of its tools and practices to experience economy, advertising or what has been labelled as “creative culture”.

GL: I am not sure we ever talked about the ‘emancipatory’ potential of new media. Access, yes, that remained a central demand, well into the late 1990s. What artists, activists or ordinary people did with these tools and channels, was their own business. Tech was supposed to be cheap and open and empower freedom and autonomy. We did not have a concept that media were supposed to uplift other groups such as minorities and ethnic communities. We were in favor of self-organization and self-publishing: sovereign media. Working with technology was done in a cheap way. It was not all about the latest and the most expensive, quite the opposite. We practiced connecting electro-trash with Amiga, PCs and Mac, with the aim to produce as much noise as possible. The aim was to overcome boundaries between people, cultures, disciplines and technologies: life as a multi-media Gesamtkunstwerk. There was no fear for commerce as it was completely absent. The appropriation paranoia only came up much later. Until the mid 1990s the Amsterdam new media scene was wild and free because of the daily cost of living there was low. This radically changed only a few years later and smashed the entire scene to pieces. Retrospectively, we can say that was a delicate media ecology.

GC: What do you remember of the Wetware convention? I found this quote somewhere: “Because of the inexperience with this kind of complex events, the Wetware Convention ended in a merry chaos and a spontaneous house party, with (what was still very new at the time) a couple of VJ’s who happily seized the available video- and computer equipment.” (Menno Grootveld). If that was true allow me to add that we also had similar events in ‘85 and ’87: the house pARTy moment—although under very different circumstances but perhaps on similar grounds, with values such as solidarity, coming together, art as sharing, celebrating private encounters, free from state surveillance–or so they thought.

GL: The Wetware convention in August 1991 in De Melkweg was the first conference and media festival that I curated, in this case together with Marleen Stikker, the director of the Zomerfestijn festival, of which Wetware was a part. I had been to Zomerfestijn events in the years before. The program contained a mix of underground theory, art, new media arts and industrial music (see the video by the Amsterdam collective Stort and their Off the Road documentary in which I appear, theorizing while biking through Amsterdam). At the time, the dirty, physical aspect of electronic media was crucial for us. The clean, New Age version of cyberspace was something that had to be polluted.

Electronic music, such as techno and house, were OK, but had an inevitable tendency to become harmless as they drifted off in the separated realms of dance, drugs and entertainment. The heavy industrial ‘rust belt’ elements grounded us in the material reality of unemployment, deserted spaces and the left-over trash of capitalism gone by, against the clean electronic order of the yuppies. The name wetware itself was an expression of that cultural discontent; it is a synonym of the human body that is connected to the hardware and software. For us, the human element, defined by its fluid desires and streams of tears, cum, urine and sweat was a revolting body that short-circuits the dry and dead New Order, against the Control Machine.

GC: From 1993-2003 tactical media existed in Amsterdam as something close to a movement that combined art, experimental media and political activism. Would you briefly introduce what Tactical media meant for you back then? What was the thing it supposed to oppose? What were the main drives to invest activist effort in it? Was it a movement more prone to activism or a something closer to theory, production of discourse and/or of discursive tools?

GL: The term tactical media is a concept that emerged out of an earlier term, ‘tactical television’, which was invented late 1992 when we put together a broad coalition of media activists and artists to organize a big festival in the Paradiso venue. Next Five Minutes, as it was called, can be seen as the international activist wing of the video art movement (with Montevideo and Stedelijk as the elite sections, operating in the contemporary arts market).

The term tactical referred to the need to have new methods and orientations after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the disintegration of the left and radical movements of the 1970s and 80s. The arts had to find a way to connect to the new neo-liberal reality of ‘the market’, the creativity paradigm and the rise of digital technologies. The term ‘tactical media’ was used for the first time by the editorial group that put together the second Next Five Minutes festival, which took place in Paradiso and De Balie in January 1996. This event happened simultaneously on public access TV, the pirate radio air waves and the internet. Retrospectively, it became known for the confrontation between Richard Barbrook and others of the nettime gang and John-Perry Barlow, who had travelled to Amsterdam to defend his Declaration of Independence of Cyberspace: was the internet a separate sphere that should be left alone or a corporate medium in need of government anti-trust regulation?

If tactical media ever opposed something, it was probably the cold insular culture of contemporary arts as an autonomous realm of conceptual forms without any reference to the outside world. The tactical temporary hybrid form anticipated, and opposed, the slack and smooth interfaces of today’s social media and its related extraction economy called ‘platform capitalism’.

GC: Did Tactical Media arrive as a form of aesthetics, a stylized form of resistance? In The ABC of Tactical Media – that you and David Garcia wrote in 1997–you spoke about a dirty aesthetic: was it similar to the deployment of the internet vernacular in post-internet art practices? Were hype, virality and dissemination seen as more affirmative than they are today in art theory and criticism?

GL: We were aware that the old way of activist mobilizations no longer worked. We needed a new visual language for the emerging ‘anti-globalization’ movement at the time. One of the outcomes was the Indymedia network, that, in part, came out of the Next Five Minutes contexts. We were indeed afraid of the clean consumerist aesthetics of virtual reality, multi-media and computer games. Tactical media proposed temporary connections and hybrid forms of uneven streams of information, people, experiences, art forms and content. Tactical means choosing what’s appropriate for the moment: a performance, street art, memes, a song or decentralized networking, any form of expression that says no to power, that occupies space and bring us together and embodies the values that we’re fighting for—and want to share. Needless to say that some things no longer work and do not speak to certain generations. But that has always been the case—and always will. The question is: do we have the courage to go out again, and experiment?

GC: What does user ‘participation’ mean today?

GL: We never spoke about participation (or tried not to). In comparison to action or empowerment, the term is shallow, too weak. The participatory rhetoric of city planning and architecture that dominated the 1970s, has rightly been criticized (then and now). Participation is a form of control. The idea of new media is not that you participate in this or that channel. The promise is one of self-organization and self-expression. Not me, myself and I but a free association of media literate actors. The problem of social media is precisely that the role of us creators is being limited to one that merely participates in the pre-defined spaces of a few others. These days, participation is an economic resource. The extraction logic of internet platforms is based on it. We should call for a participation strike and see what happens. Right now this is a utopian gesture, a silly dream. Look at the tiny impact the Cambridge Analytica scandal has had. People cannot afford to abandon their participation. We’re trapped.

GC: Could we have a better understanding of both contemporaneity and community-built-resistance, than that of an alternative/outside/counter-cultural resistance that refuses assimilation or contagion with forms of domination? Should ‘we’ ditch Facebook, delete Instagram and go out and live ‘in harmony with nature’, thereby increasing prices through our ‘mindfulness-travel tourism’? Or should we, as this decade’s left and neo-reactionary accelerationist aesthetes, turn capitalism into a hyperbolae and submit to its delirious flow to its own destruction?

GL: Acceleration or resistance, is that what you’re pointing at? Accelerationists are not hyper conformists. And activists that resist and call for an exodus never really manage to leave the stage altogether. This is because of the mess we’re in. We’re incapable of executing the consequences of such pure positions. Look at the false political choices we’re confronted everywhere: instead of Trump, would you have rather voted for Hillary Clinton and her war mongering globalist ‘deep state’ elite? In Europe, the choice is not all that different, between nationalist rightwing parties and the globalist, austerity-loving neo-liberals. Against the potentially orthodox and marginal ways in which such debates tend to go, we’re living a life of trail and errors of ‘minor media’ experimentation that understands that current dynamics between social life and communication technologies.

GC: I’m under the spell of a passage from the Invisible Committee, in A Coming Insurrection: “The past has given us much too many bad answers for us not to see that the mistakes were in the questions themselves. There is no need to choose between the fetishism of spontaneity and organizational control; between the “come one, come all” of activist networks and the discipline of hierarchy; between acting desperately now and waiting desperately for later; between bracketing that which is to be lived and experimented in the name of a paradise that seems more and more like a hell the longer it is put off and flogging the dead horse of how planting carrots is enough to leave this nightmare. (…) To organize is not to give a structure to weakness. It is above all to form bonds – bonds that are by no means neutral — terrible bonds.”

Is there any hope left that social movements (powerful, lasting and efficient) can emerge out of new media infrastructures? Are trouble as well as solutions inherent to the medium? I am thinking now of a quote of Paul Virilio who said: “The Internet is like the Titanic. It is an instrument which performs extraordinarily well and yet contains its own catastrophe.”

GL: New crises will provoke new forms of resistance and self-organization. They, in turn, require their own form of communication and coordination. Right now, we seem to be a never-ending social bubble and cannot possibly see a way out. We’re trapped–and it’s nice inside there, notwithstanding the fact that we get very little done this way. The tech is personalized, intimate, holistic. It is boring yet addictive. I am not sure if the internet is like the Titanic. If only. In that way the Accident will happen, and then it is done and over with it. This is the secret cataclysmic moment many of us were hoping for. I am no longer sure it’s going to end that way. Perhaps the next recession will be a life-long meddling with precarity. What are we waiting for? Are we the living-dead, slaves of Marc Zuckerberg, dreaming of the next festival, night out, escape travel? We can do better than that.