‘SAD BY DESIGN’: Interview with Geert Lovink by architect and researcher Hande Tombaz

Hande Tombaz: You define sadness as a possibility of reflection. The way you describe the term sadness largely refers to the concept of melancholy, which is a more complex emotion than sadness. However, what we are experiencing today through social media is more likely to be characterized as a depressive mental state. How would you describe this phenomenon?

Geert Lovink: In my book Sad by Design I contrast technologically induced sadness not just with the historical ‘illness’ melancholy but also with boredom, depression, loneliness and similar sombre mental states that are dominant today. We read a lot about ‘male’ anger, from trolling and shitstorms to cyber-warfare but less so about the regressive side. Emotional rides are no longer experienced in solitude, the virtual others are always there as well. It is a truism that we are lonely together (a subtle but crucial variation of Sherry Turkle’s alone together). We cannot put the phone away, there is no relief. In my essay, I have tried to minimize the comparison between the current wave of technologically-induced sadness and the rich historical descriptions of melancholy. I am cautious to overdetermine the ‘behavioural surplus’ techniques, as described by Shoshana Zuboff, by never-ending art historical readings of the same old Aristotle, Dürer’s Melencolia I, supplemented with Burton’s Anatomy, closed with a Susan Sontag quote. Phone and mind have merged. We have to describe and theorize the disturbing perpetual now and not reduce it to a type of academic historicism that refuses to engage with the current digital regime that-literary-rules the daily lives of billions. The predictable continuity thesis is not just elitist, it is escapist. It walks away from the dirty present, much in the same way romantics did in the industrial 19th century.

The techno temperaments are generated by computer code and interface design (also known as nudging) causes overload and exhaustion and produces a gloomy state that flickers, without ever becoming dominant on the surface. Sadness today is an indifferent micro-feeling, a flat and mild state of affairs. This should be contrasted with the much heavier illnesses such as depression, stress and burn-out. One or two centuries ago these would be labelled melancholia. Some artists make this an explicit topic of their work such as Lil Peep and Billie Eilish. Sadness is no longer hidden and is becoming part of pop culture. Youngsters feel the anxiety, the stress, and become sad about empty promises and diminishing opportunities. They’re experts at reading daily life through the sadness lens. This does not mean we should medicalize them. We are not sick. How do we comfort the disturbed? Not by taking their phone away. What can we do that’s liberating and prevents moralism?

I consider melancholy a thing of the past because there is simply no time anymore to indulge in a wistful state. This is why melancholia disappeared. One could, of course, defend that techno sadness still bears the possibility of melancholy. In my view, the implosion of the factor time has all but sabotaged the possibility to seriously drift off. Realtime machines constantly draw us back online, capture our attention and do not allow extensive mourning. Strangely, melancholy requires concentration and focus. Distraction on the other is all over the place and is sadness is ‘micro-dosed’.

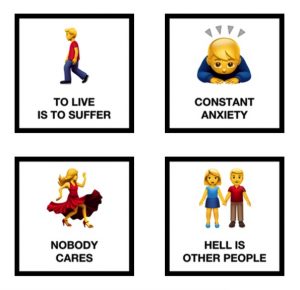

(from: https://existential-emoji.com/)

The acceleration of experiences, the density of our busy lives, the compression of feelings, the roller coaster ride of mental states (induced by drugs, but also travel), this all makes it impossible to have the blues. Hyper-capitalism does not allow negativity. Feedback is reduced to taste and ‘performance’. We could say that all states of mind can and will be exploited and commodified—and this is increasingly the case with sad music, sad t-shirts, etc. but organized positivity is still dominant. Negativity can easily turn against capitalism itself. Slowing down as a moment of ‘digital detox’ can be seen as a product that can be purchased, but what if this turns into a riot or a strike? Capitalist accumulation is driven by ‘organized optimism’, orchestrated by New Age managerialism. Dark states of mind are considered individual deceases that can be overcome by therapy. Capitalism is said to be able to deal with all the contradictions it produces. It is not.

The problem with (historical) melancholy is that it still is an individual attribution. We moved on and became post-human, cyborg, wetware, datadandies. Today’s sadness is a system, an assemblage of mind, body and techne. Intuitively, many feel that their mental mess is produced by society, it is not a sickness in our heads. Contemporary culture recognizes this and teaches us that every situation, every object and service can and will be sad. This is why we feel trapped and do not see how collective action can lead to change. The world’s state of affairs is causing many to become depressed. This is why the medicalization of the discourse will not be adopted, despite massive efforts to push it onto us.

HT: Soren Kierkegaard is one of the key figures in the conceptualization of melancholy. In his article ‘Over the Bridge of Sighs into Eternity’ from 2006 Karl Verstrynge writes about the concept of melancholy in Kierkegaard’s thought and states that: “Kierkegaard more often settles into a typically modern context by associating melancholy with heavy-mindedness and analyzing it as a wilful isolation from actuality”. However, you claim that “While classical melancholy was defined by isolation and introspection, today’s tristesse plays out amidst busy social media interactions.” Isn’t that also some kind of wilful isolation from actuality? In the context of the social media environment, how do we experience this isolation? And do you think that this experience has any potentiality?

GL: Ever since Robert Putman’s famous 2000 study Bowling Alone, we’re aware of the growing role of singles, individuals who live on their own, either voluntarily or not… Here in the Netherlands, this was discussed in the 1990s as ‘individualization’ (not to be confused with Simondon’s ‘individuation’, which is close but a different term). The statistics of individualization in Western societies such as the Netherlands, in Scandinavia but also in the UK, Japan and the USA is overwhelming and historically coincides with the rise of the internet. But is this a failed isolation, a pseudo-state. The feeling of being ‘alone together’, as Sherry Turkle adequately described it, is widely recognized as an accurate description of the status of the social. Not alone but still lonely. This situation is not a proposition of me. It is not an opinion or a ‘version’ of reality. The smartphone use is widespread, in most parts of the world, as is loneliness. Should we still discuss this?

Techno sadness is not a symptom of withdrawal (from society, from others) but a sign of temporary collapse, not being able to cope anymore, albeit a sensible, slow gesture, not a violent, dramatic breakdown. I take the freedom to classify Kierkegaard a 19th-century thinker who lived parallel to his unfolding industrial age. Can you imagine what would have happened if he, and Nietzsche, for that matter, would have completely internalized machinic (and media) thinking into his melancholy theory? Even Marx, his contemporary, was not really able to incorporate the machine in his thinking (except for one, now famous fragment). This is not a critique. We know that the study of the bourgeois subjectivity was a product of Romanticism and was (literary) distanced from the (proletarian) machinic reality, which in fact only a minority was exposed to in Kierkegaard’s lifetime. Kierkegaard’s provocations were addressed to Christianity, not the lack of understanding of the industrial age he unfolded during his lifetime. However, Kierkegaard is important in the contexts of pessimism and anxiety, which are relevant in our technological age.

HT: You’ve proposed the new term ‘social reality’ (in contrast to VR and AR) to describe the mighty presence of social media. How does this reality affect us as socially constructed beings?

GL: The term is a gesture towards start-ups and geeks but is also addressed to funders and researchers to take social media more seriously. Right now, social media are either the domain of marketing or an object for (moralistic) concern of teachers, parents, politicians). Critical internet research is still a joke in terms of funding, schools, research programs. The internet has been around only 25 years old (even though academics should know better, it is in fact 50 years old). Institutions are slow and the outgoing baby-boomers never showed much interest in anything digital. No one loves to be disrupted. Social reality (SR) is so much larger than hyped-up technologies such as virtual and artificial reality. SR is also am ironical hint to sociology, the discipline that so far has failed to contribute to a better understanding of the ‘social in social media’ as I called it in 2012 in e-flux, an essay I updated in Social Media Abyss. I no longer believe there is some raw and truthful reality outside of the social worlds that tech companies have created.

Dichotomies such as online-offline and real-virtual are no longer meaningful. I like the idea of a social reality that people carry with them. Once they grab their phone and start swiping and scrolling through the updates on their ‘social’ apps they are in it again. You go on ‘social’, as the Italians say. Have you seen it on ‘social’, as the Italians say. We need to re-invent the social, which is now technical and digital. I would not say it ‘affects’ us as such an understanding somehow suggests that we are outside, victims, subjects. The user perspective teaches us that we’re fully involved—by design—and constantly interact, contribute, upload, klick, respond, like, swipe, whatever. The extractive data machine lives of that.

HT: How would you define the relationship between social media and design? From the perspective of post-humanist philosophy, do we also design ourselves through social media?

GL: Yet another tragic topic. Most of us would not even notice that social media are regressive in terms of design; they look ordinary. We do not even notice how they look. This non-design stands in stark contrast with the experimental interface design from the 1990s. In the design manifesto Made in China, Designed in California, Criticized in Europe that I wrote with designer Mieke Gerritzen for the temporary Droog space in Amsterdam we describe the transformation of the design industry towards self-design. If more and more aspects of the exterior world have already been designed, or are in the process of being beautified, what remains is the interior world of the self. Design is here seen as a discipline that not just paying close attention to the visual quality of objects and services. Everyone and everything is being subjected to design. This includes the world of labour and organization where we see the rise of ‘design thinking’. All social interaction can and will be designed. This is a rather cold and cynical development in which the exclusivity of the visual experience is overruled by the smoothness of the process. What strikes me in this ‘democratization’ of design is the speed in which we get used to new products and services. What was new and chocking yesterday, is completely self-evident today and will be invisible and sub-conscious tomorrow.

To answer the second part of your question, self-design through social media is widespread but not exactly known under this rubric. Self-design can be a somewhat naïve term. The daily reality, in particular for young people, is a brutal one, in which the construction and maintenance of the self-image is a matter of life and death. We should not underestimate the internalized values of the neo-liberal precarious reality in which people are forced to compete with each other and life never quite succeeds. There are always mishaps, fall-outs, missed opportunities, break-ups, strange downtimes in our mood, an endless period of boredom in which nothing seems to work. The self-image constantly breaks down, we get angry or depressed, can’t finish a deadline. This is all recorded and captured, processed and turned into data points that are added to our profile. Self-image is no longer a cute selfie, it has become much more complex and contradictory.

HT: In his 2009 book The Melancholia of The Cyborg Fernando Broncano states that we are all hybrid beings living on the edge between natural and artificial worlds. This liminal situation reveals a kind of melancholy. He also states that “Melancholia is not a state of disenchantment, but a state of knowledge or wisdom. Modern melancholia is the melancholia of unrealized possibilities. It is therefore not a kind of infirmity or malady, but the very nature of frontier beings.” How do you interpret this statement based on the fact that we are transforming our beings through social media?

GL: I like the possibility. For sure we can design systems that are based on other values. Current social media are not even remotely based on the ideas you express here. They are not virtual worlds where one hangs out—if only. There is nothing psychedelic about them. Let’s hope the content is half-way cool. The functionality is boring, so dull that we don’t even see it. This is why we get used to a new app after a day. Every square millimeter is utilized, sensitized, hyped up, linked to ads, designed as traps to extract even more data. Terms like knowledge and wisdom are a complete joke, utter lies or newspeak when it comes to Facebook. We need a massive exodus first, and then the dismantling of the Facebook and Google infrastructure, otherwise our demands for a decentralized internet will remain empty and futile. I do not believe socialization or nationalization will change the situation. Monopolies need to be actively taken apart. Some say that the next social media will be hang-out places, much like the 1990s virtual worlds. This is a relaxed view of the future. I fear the next decade will not be so chill, but that’s something we can discuss. The point is, we cannot imagine the social in terms of the cyborg. This is not about natural or artificial worlds. The social is very real, messy, ugly, sexy, and boring for most of the time, cutting straight through the postmodern lingo.

HT: How would you define the role of technology, especially social media, in speculative design practice?

GL: Silicon Valley has all but killed the speculative imaginary—and they are acutely aware of that. This was their aim. Not merely own it but shut it down by pulling it into the background. A growing movement is reclaiming the net but it’s an uphill battle. It sounds weird but ‘another internet is possible’ has almost become a subversive slogan. If we want to overcome homo extractionist, we need to organize and fight, in visible manners, build and use those f*cking alternatives we desire so much! Stop crying. We cannot make fundamental changes unless anti-trust measures move in fast, split up the giants and dissolve them. Regardless, regulation will be not enough to reinstate a decentralized internet as public infrastructure. We need to socialize cables and remove Silicon Valley interests from key internet governance organizations such ICANN, IETF and actually rewrite protocols and bar them access. The influence of platforms on the deep levels of the internet cannot be overstated and needs much more attention. Fake news, algorithmic hatred and secretive moderation offices that have to then repair the damage, are only surface phenomena and can be dealt with by PR massage and perception management. The power over infrastructure is the real fight and we need to politicize that space.

Right now, there is hardly anyone working on the speculative re-design of the social. This space has been poisoned by the systems of likes, followers, updates, newsfeeds, ‘friends’ you name it. Let’s get rid of this jargon. However, we want to reinvent the social we need to acknowledge that we can no longer distinguish between the social and tech. Forget offline romanticism. Secondly, we need to get rid of the Silicon Valley online presence inside our conversations, our lives. Let’s minimize the presence of third parties and focus in a pragmatic way on what needs to be done and what tools support this strategy. No more invisible moderators, filters, censors. The algo ain’t no friend of mine. Alt.social will have to confront itself with various challenges: monetization and democratic decision making. Both aspects have been quietly removed from Silicon Valley’s agenda and their related start-up venture circles. For art and activism redistribution of the ‘wealth of the networks’ and collective decision making are essential. We need to dismantle the ‘free’ and invent new ways to work together and deal with difference and disputes. We can no longer delegate the management of the world to these IT firms. Silicon Valley is part of the problem and we no longer expect them to resolve the growing tensions in the world.

Amsterdam, September 5, 2019