When one inquires about the products of the specifically modern aspects of contemporary life with reference to their inner meaning – when, so to speak, one examines the body of culture with reference to the soul, as I am to do concerning the metropolis today – the answer will require the investigation of the relationship which such a social structure promotes between the individual aspects of life and those which transcend the existence of single individuals. It will require the investigation of adaptations made by the personality in its adjustment to the forces that lie outside of it. Georg Simmel, ‘The Metropolis and Mental Life’ (11)

In ‘The Metropolis and Mental Life,’ Georg Simmel gives a thorough account of the peculiar circumstances that city residents experience in daily life. Particularly in his call to investigate the connection that an urban ‘social structure promotes between the individual aspects of life and those which transcend the existence of single individuals,’ Simmel grapples with a fundamental challenge that all city dwellers must face: to be one in a world of millions, to seek a sense of individuality in an environment structured around the seemingly infinite presence of others, all looking for some way to define themselves similarly.

Queer and trans people are not the only ones who struggle to seek self-definition in this overwhelming climate, of course. But in navigating cities defined by cis-heterosexuality, patriarchy, white supremacy, and capitalism, the struggle to understand one’s individuality against these hostile forces takes on a fraught urgency. In a climate shaped by attitudes, norms, and material forces which run counter to our well-being, we may ask: How should we be expected to find sufficient reserve within ourselves to construct a hopeful narrative for the future? How do we reconcile ourselves to the hostility of our surroundings?

To better understand the complexities of self-definition in this climate of fear, doubt, and uncertainty, I draw upon the work of French philosopher Gilbert Simondon, particularly his conceptualization of the ‘transindividual.’ Despite never writing about trans people at any point, Simondon’s concept nevertheless holds resonance with my lived experience as a trans person. Extending Simmel’s description of urban life as the reconciliation of individual subjectivity with collective, external experiences, Simondon’s philosophy of individuation explicitly argues that there are no individuals, only processes of perpetual individuation.

Simondon’s claim may not at first seem much different from a perspective that recognizes factors like ideology, social norms, and history as determining forces on our thinking. However, his emphasis on the impact of the milieus that shape us makes tangible the environmental factors guiding the individuating journey, saturated with social and ideological forces that never fully delimit potential future changes to come. By explicitly considering the relationship between urban space and digital space as two crucial milieus that queer and trans people navigate on the path towards individuation, I will try to name the kinds of spaces that I’d like to see in a queer future to come, drawing upon the work of artist Edie Fake, writer Renee Gladman, and artist Bodys Isek Kingelez for inspiration.

Enlarge

INTRODUCING SIMONDON

Gilbert Simondon, a mid-20th-century French philosopher, has seen his influence gradually widen over the course of the last several decades. While much of his philosophical legacy has been subsumed by Deleuze’s incorporation of Simondon in his writing on the theme of becoming, it’s worth engaging with Simondon’s own texts and the many other adaptations of his thinking in recent years, to get a full sense of Simondon’s ongoing significance. (For the most straightforward English-language introduction and contextualization of Simondon’s philosophy, I recommend Muriel Combes’s Gilbert Simondon and the Philosophy of the Transindividual, translated by Thomas Lamarre; for the best book of essays by scholars interpreting and applying Simondon’s theories today, I recommend Gilbert Simondon: Being and Technology, edited by Arne De Boever, Alex Murray, Jon Roffe, and Ashley Woodward. Both texts are cited in this piece.)

The essential concern at the heart of Simondon’s approach is the replacement of ontology with ontogenesis – an analysis of how the world becomes, not what it already is – and a focus on the process of individuation rather than on centering the individual subject as such. To grasp this process, Simondon also asks us to understand the significance of the milieu, or the social environment surrounding a subject, through which the act of individuation can emerge.

If ‘we may consider individuals as beings that come into existence as so many partial solutions to so many problems of incompatibility between separate levels of being,’ as Muriel Combes describes Simondon’s thinking, we can grasp individuation as an act of perpetual problem-solving, our individuating subjectivities constantly divided amongst the many competing challenges we face. Through these ideas, we can begin to see the relevance of this work to the question of queer politics: How do we individuate as a series of partial solutions that are largely determined by the particular milieu in which we find ourselves, especially in the hostile environment of 21st century networked capitalism, global pandemic, and climate change?

Simondon’s definition of the transindividual and his emphasis on relationality as the way in which we come into being, offers a hopeful articulation of the significance of queer kinship as a perpetually generative process of becoming. Combes suggests that the ontogenetic claim essential to Simondon’s philosophy ‘is that individuals consist in relations, and as a consequence, relation has the status of being and constitutes being.’ Simondon connects the individuation of singular beings with a concurrent individuation of the collective, which he refers to as the subjective and objective transindividual, respectively. (It is this dual process of simultaneous becoming that takes place both individually and collectively, that explains Simondon’s use of the trans- prefix.) In this sense, the transindividual ‘appears not as that which unifies individual and society, but as a relation interior to the individual (defining its psyche) and a relation exterior to the individual (defining the collective): the transindividual unity of two relations is thus a relation of relations.’

For Simondon, the act of becoming, rather than simply being that which connects individual psychology and collective sociology, is inherent in both forms of the transindividual. Psychic and collective transindividuals both manifest latent pre-individual elements that accompany them at all times, a persistent source of renewal and possibility that generates new individuating paths. As Combes states it: ‘What gives consistency to individual psychic life is found neither inside the individual nor outside it, but in what surpasses it while accompanying it, that is, the share of pre-individual reality it cannot resolve in itself.’ Simondon further describes the relation of one’s psychic individuation through the notion of affect, suggesting: ‘affectivity, in effect, puts the individual in relation with something that it brings with it, but that it feels quite justifiably as exterior to itself as individual….’

Such an image is an evocative description of the ways in which each being carries beliefs and attitudes which constantly exceed its individuality, a fact that describes hopeful affects like queerness as much as it does the persistent stream of racist, sexist, and other harmful thoughts that often populate our minds against our will. If ‘thought is rooted in a milieu, which constitutes its historical dimension,’ as Combes writes, we would do well to accept that our being and our psychic individuation are conditioned by the world we move through and the preindividual elements anticipating our arrival into becoming, without foreclosing the possibility of creating new environments through social life that will in turn further reshape our transformation.

In her chapter ‘Identity and Individuation: Some Feminist Reflections,’ Elizabeth Grosz makes the case that the construction of transindividual collectives can offer important insight for feminist and radical thinking today. In a discussion of identity categories which are frequently invoked as naturalized social forces, Grosz argues that ‘these categories are neither structures nor forms, neither intersected nor singular and self-identical.’ Instead:

They are social collectivities, transindividual groups, that cohere not only because they share a common milieu (the environment of various forms of oppression) but also because they share some kind of internal resonance, some form of informational coding that brings together their members, in various degrees of adhesion, to social / political collectives.

As Grosz notes, one essential characteristic defining marginalized peoples’ milieu is that it is an ‘environment of various forms of oppression.’ Still, there’s much more than a shared experience of harm that binds collectives together. Indeed, there is ‘some kind of internal resonance’ that exceeds the negative forces of structural violence and deprivation to knit together disparate peoples. As a small personal example: for reasons as of yet not fully understood to me, many trans femme people seem to love rats. This detail, perhaps insignificant outside the community, is nevertheless a common source of recognition that I share with many other trans people, somehow floating in our shared pre-individual imaginations and manifesting in various forms through the process of individuation.

The ‘various degrees of adhesion… to social / political collectives’ reflect the sense of incomplete individuation essential to Simondon’s approach, suggesting that even the most self-evident identity categories are better understood as contingent forms of pre-individual realities, reference points to be negotiated with, contested, and assimilated over the course of one’s lifetime. Even if we cannot always escape the ways in which perceived social categories like race, gender, or sexual orientation shape how others treat us, these broad identities are nonetheless contingent, prone to taking on evolving impacts in our lives in the same ways that political affiliations, religious beliefs, and subcultural identities shift and mutate, never fixed in place.

After considering Simondon’s thinking in detail, Grosz ultimately concludes that:

What Simondon offers to feminist and other forms of radical thought is a new way of understanding a world that is not ultimately controlled or ordered through a central apparatus or system, that has no inherent or necessary hierarchies, that does not require animation or coordination by culture but instead enables and makes culture itself possible.

Grosz suggests that Simondon’s approach renders every identity category, however seemingly fixed, as more fluid, contestable, and indeterminate than previously imagined. Without rendering identity politics, intersectionality, or Marxist class analysis obsolete, Simondon’s emphasis on perpetual becoming is nevertheless an anti-essentialist approach to identity, suggesting that no ‘central apparatus or system’ is determinate of how we may individuate through the identity categories available to us within our given milieu. In short, Grosz argues that radical movements can avoid creating a kind of politics based wholly on subjective identities:

Subjective identity is not the stable and abiding identity that founds a politics, whether it be a politics of recognition or an egalitarian politics of formal similarity. Simondon understood a world in which unities and stabilities are always capable of further elaboration and evolution; unities and stabilities were never unified or stabilized enough to remain unchanging universals.

If identities are not ‘unchanging universals,’ how do they evolve? Simondon calls the process of cobbling together heterogenous factors into temporary solutions ‘transduction,’ an act that is always already provisional by nature. As an example, in queer history, particularly queer urban history, the creation of community spaces free from the heteronormative gaze of others has always been an essential task; while we may not escape wider forces of discrimination, making spaces like bars, nightclubs, and queer health centers is always a partial solution to countless ever-present adversities, certainly an ‘[adaptation] made by the personality in its adjustment to the forces that lie outside of it,’ as Simmel described the urban experience. Thus, we can understand transduction as ‘a mode of territorialization or spatialization[:] a mode of production of a field or terrain that surrounds and enables the being and its transformations,’ as Grosz argues.

Unsurprisingly, cities, with their dense and lively atmospheres and heterogenous sources of opportunity and interactivity, have historically been uniquely valuable for queer people; economic precarity and social marginalization tend to accompany us wherever we go, but physical proximity offers new forms of protection and identification that sustain us. This line of thought can also be followed onto the internet. Today, we must consider the task of creating new digital spaces informed by the valuable lessons that we have learned in our experience navigating visibility and vulnerability in urban environments.

STANDING AT THE ENTRANCEWAY OF A QUEER BAR: DEFINING QUEER SPACE AND HIDING IN PLAIN SIGHT

It is in this sense that I think of the entranceway of a queer bar as a useful metaphor for what we must demand of the digital spaces of the future. In ‘Spiderwoman,’ an essay by Eva Hayward included in Trap Door: Trans Cultural Production and the Politics of Visibility, she writes:

I live directly across from Diva’s. Standing outside the bar, at all hours, are dazzling women. Their heels cantillate, sounding out the streets. They gather at the entry of the bar, which recedes from the sidewalk just enough to offer shelter and vantage [….]. Differences in race, ethnicity, and class are not lost – going into Diva’s, you are confronted with how race territorializes – but necessity makes the entry a temporally shared space between these glittering women. A glistering threshold – charged with desire and fear – the doorway is the only common ground. Even still, every entry is also a foreclosure. An open door is a closed door, too.

Enlarge

Hayward’s description of the threshold offers a window onto the current shortcomings of digital space. Even on the street, the physical architecture of the bar and its receding entryway push back from the outside world ‘just enough to offer shelter and vantage,’ a first step into something more protected inside, a milieu safer than the wider world outside its doors. As Hayward suggests, physical embodiment through race, ethnicity, and class fail to disappear inside the bar, but as ‘necessity makes the entry a temporally shared space between these glittering women,’ we sense the value in coming together across our individuated and individuating differences. If ‘An open door is a closed door, too,’ as Hayward states, it suggests that we might be able to shut the door behind us, so to speak, to welcome people at the threshold in need of entrance a way in, still creating a meaningful buffer to hostile forces which may lurk in the shadows outside.

Navigating through the perils of visibility and violence, connection and erasure, is not new to trans life, of course. But in digital space, a realm that loosens gendered expectations and creates new kinds of openings for people to explore alternative experiences of individuation that may only come into physical transformation later on, the need for new ways of protecting ourselves is acute.

I would argue that turning to the history of trans digital space offers several clues that can inform new practices today, recognizing the necessity for more control in a milieu of normative platforms that seek our erasure. In Henry Giardina’s ‘An Oral History of the Early Trans Internet,’ he quotes Gwendolyn Smith, founder of the Transgender Day of Remembrance and ‘The Gazebo,’ an early AOL trans femme chatroom, who said:

In the early days of AOL, you couldn’t have a public chat using the word “transsexual” or “transvestite.” They’d find you and switch the forum to private, and no one would be able to find you. We had to be clever about it. There was a chat called “Christine Jorgenson” that threw them off the scent for a while, then there was one called “Virginia Prince.” They would always find us and shut us down, even when we started using terms like MTF and FTM. AOL had these people searching for banned words and they would eventually find us.

The above quote reveals the continuous dance that trans people have always played with authority, whether online or offline. The specific use of identifying keywords outs trans people on platforms beyond their control, much as real-life visibility often invites the specter of police violence and street harassment. Yet in channeling the legacy of trans elders like Christine Jorgenson and Virginia Price, these early-internet visionaries found a way to transindividuate in plain sight, offering signals of refuge to those who knew where to look for them.

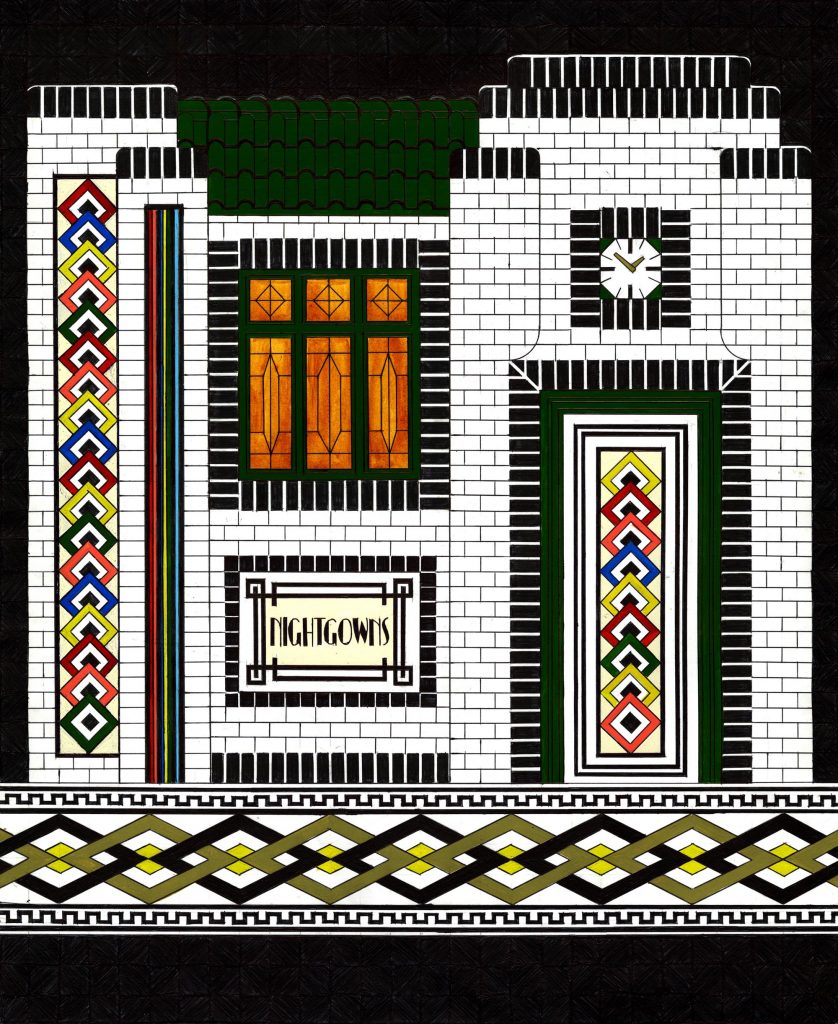

I find a similar resonance of Hayward’s description of Diva’s and the hiding-in-plain-sight quality of the early trans internet in the work of Edie Fake, a formerly Chicago-based artist, whose Memory Palaces project links queer history with a speculative architecture of the future. Another quote from Hayward’s description of the women outside Diva’s could work just as well to describe Fake’s imagined facades, whose names are drawn from Chicago’s queer past. Hayward writes: ‘They are hyper-visual and their shimmer, sparkle, dazzle also confuse vision, an excess that clouds the question of visibility; the gilded surface deflects a desire for depth even in its allure.’ If the obvious visibility of both Diva’s trans clientele and the imagined future architecture created by Fake invite the possibility for repression, so too do they offer a kind of refuge that trans people rarely find on platforms like Twitter today. Even as recent leaps in trans visibility create new forms of danger, they also allow more people like myself to find themselves in queerness.

The task now is to find a space for seclusion and connection, untethered from the normative expectations of others, both physical and digital. While those who draw hard lines between digital and physical space reinscribe another form of Cartesian dualism that has stubbornly tried to split mind and body for centuries, others who have fought to create safer online spaces recognize that such separation often makes little sense. In the 1993 article ‘A Rape in Cyberspace,’ which galvanized attention around the emergent phenomenon of sexual violence in virtual worlds, author Julian Dibbel described sexual contact on a multi-user dungeon, a common early-internet text-based virtual space. Rejecting a firm binary between physical and digital experiences, he argued that users ‘[recognize] in a full-bodied way that what happens inside a MUD-made world is neither exactly real nor exactly make-believe, but profoundly, compellingly, and emotionally meaningful.’

That the virtual rape in question was first directed at a character named legba, ‘a Haitian trickster spirit of indeterminate gender, brown-skinned and wearing an expensive pearl gray suit, top hat, and dark glasses,’ is not incidental: even as digital space offers room for gender play and new avenues for individuation beyond the constraints of physical embodiment, the real threat of misogynist, transphobic, and racist violence persists. Finding new ways of protecting ourselves online, then, is not a retreat from fighting for material protections. As we recognize the virtual realm as an essential space for trans becoming, we become more attuned to our physical survival as well.

DREAMING OF THE CITIES OF THE FUTURE

I like to imagine the digital and physical spaces of the future as realms in which we are ‘affirmed as a “singular point in an open infinity of relations,”’ as Simondon evocatively describes ethical activity for a relational subject. Combes further describes this project as the task of ‘[constructing] a field of resonance for other acts or to prolong one’s acts in a field of resonance constructed by others; it is to proceed on an enterprise of collective transformation, on the production of novelty in common, where each is transformed by carrying potential for the transformation of others.’

In practical terms, I view this work of virtual space-making happening today on Are.na, an exceptional platform that I use to connect my research work to the work of countless untold others. By making available people’s channels of existing collected information once I’ve linked a given URL, I’ve quickly discovered new forms of knowledge that became accessible after my first effort to look in a general direction, another form of hiding-in-plain-sight utility that certainly embodies the ‘production of novelty in common’ described above. It is a constant reminder that the raw materials necessary to reimagine better forms of life are already available to us; the challenge is navigating in and through structures, whether physical or digital, that prevent communities from creating new kinds of milieus that can substantially aid in their perpetual becoming.

Enlarge

More speculatively, I’m drawn into two other visions of cities of the future, through the work of Bodys Isek Kingelez and Renee Gladman. According to MOMA curator Sarah Suzuki, ‘[Bodys Isek] Kingelez was born on August 27, 1948, in the village of Kimbembele-Ihunga, approximately 370 miles southeast of the city of Leopoldville (now Kinshasa).’ Growing into adulthood in the complex environments of postcolonial and authoritarian Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kingelez was deeply impacted by life in the capital city, a place designed for 400,000 people that’s now home to 11 million residents. Taking the built environment as inspiration, Kingelez began creating city sculptures in the early 80s, in time creating dynamic urban environments that reflect the fluid temporalities present in any city.

Enlarge

Architect David Adjaye notes Kingelez’s relationship to the broader sense of hopefulness still present as a latent preindividual force for many Africans amidst the demise of decolonization efforts in the second half of the 20th century. He writes:

While Africans lived amidst the aesthetics of poverty, they were also keenly aware of the larger world, and this relationship has impacted the collective psyche. It is in this context that Kingelez is interesting: as the boy from a Congolese village with a futuristic vision not just for the place where he lives but for the world – a vision spurred by his lack of experience with the conditions he envisions.

Although Kingelez’s theatrical architectural sculptures appear resolutely focused on an as-yet-inconceivable future, they nonetheless mix temporalities in ways that reveal the latent virtuality present at any moment in the perpetual process of becoming. Igbo-Nigerian artist and curator Chika Okeke-Agulu describes Kingelez reflections on Kimbembele Ihunga, a work ‘depicting his place of birth in both its past, present, and future manifestations’:

The work is not merely a futuristic fantasy; it is also a meditation on a past that never was or on a reality that the artist has placed in perpetual doubt. It conflates temporalities: the work is a reflection neither on Congolese architectural heritage nor on its present urban realities, and we are not even sure that Kingelez was prognosticating about an architecture of the future.

This conflation of temporalities, an invocation of ‘a past that never was or… a reality that the artist has placed in perpetual doubt,’ is a reminder of the surprising ways that we change and can be changed by our world. Perpetual becoming is an act of pulling unlikely outcomes from our surroundings, defying internalized assumptions about our being, the persistent return of preindividual hopes and desires propelling individual and collective transformation. Elizabeth Grosz puts it well, noting the lively makeup of possible outcomes available in every moment, marked by the ‘memory’ of unruly potential:

The virtual forces of the pre-individual, in not being entirely used up by processes of actualization, remain an ongoing source of transformation, the generation of new virtualities and new paths of actualization. These constitute a kind of “memory”, an inherence of the past in the present and of the virtual in the actual, an inherence within the individual of the pre-individual resources whose disparity brought it into existence and which remain to regulate its ongoing individualizations.

Edie Fake’s past-future facades, and the similarly mixed temporalities and spatialities of Kingelez’s urban domains, push us toward ‘the generation of new virtualities and new paths of actualization’ in physical and digital space.

Enlarge

To further understand the latent potentials we may find in (re)creating and (re)inhabiting the cities of the future, I look to the writing of Renee Gladman, particularly her essay ‘Cities of the Future, Their Color.’ Quoting from the essay is nearly impossible, thanks to Gladman’s additive, shape-shifting prose. Still, even in short bursts, the text ripples with optimism and futurity, narrating a city responsive to the bodies of its residents, as when Gladman writes: ‘These were queer geometries, someone had said, because the bodies brushing the landscape rearranged the outdoors; the cities responded to what your clothes said you needed.’ If Winston Churchill’s famous quote, ‘We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us,’ suggests a somewhat static, closed loop between humans and their surroundings, Gladman’s urban imaginary creates space for simultaneous becoming on all fronts, internal and external, a call-and-response between our cities and our bodies more in line with Simondon’s approach:

I wanted a conversation with the buildings I entered, for the building to say something and my brushing it to respond, for it to allow its lines to move, to roam within its shape, such that to enter it would be to go on talking, to make everything you did a matter of space, an ongoing equation asking, What is your body doing, what does it need?

In Gladman’s imagination, I am further reminded of Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower, specifically the lines ‘All that you touch, you change; all that you change, changes you.’ When we are capable of holding ourselves open to one another and to our cities, an act of vulnerability that can all too easily be met with violence, change and becoming emerge in real time; despite the risks involved, we transform our world as it transforms us in turn.

Even as the urban imaginations of Kingelez, Gladman, and Fake feel utopian in so many ways, so difficult to imagine in a materialized form from the place where we currently stand, their evocation nonetheless beckons us in their direction, activating desires that begin to actualize potent longings. As M.R. Sauter notes in their essay ‘City Planning Heaven Sent,’ quoting Lewis Mumford: ‘No Where may be an imaginary country, but News from No Where is still news.’ Even if I cannot inhabit the city of the future just yet, I feel its inevitable pull guiding me forward; I am led to the streets, to fight back and to organize, feeling longing manifesting in new relational configurations brought forth by protests against capitalism, police brutality, and the stultifying status quo that denies all of us the right to continue personal and collective individuation in cities inhabitable by us all.

In this floating future space, I find an optimism that’s not easily maintained in our current climate. Through each of these speculative projects, all rooted in turbulent pasts that nevertheless do not delimit what the future may be, I feel projected into worlds I can only hope will become actualized in some form, their wisdom rooted in bodies longing for a city that can truly be called home.

I end with a quote from Fake, explaining his intentions for engaging with the built environment. Fake suggests that Memory Palaces serves as a ‘floating potential for queer space,’ rather than a lament of what’s been lost. ‘It’s not about that at all,’ he says. ‘It’s a celebration of a fantastic space that has happened and could be the basis for something even more fantastic to happen in the present.’ As we ponder the ways in which queer and trans communities have perpetually exceeded the narrow constraints placed upon them, flourishing in spite of generations of oppression, we may imagine an unending present cast in doubt crystallizing into something temporarily inhabitable, carrying within it the seeds of potentials past and future.

Annie Howard is a master's student in urban planning and policy at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and a freelance journalist. Their work can be found at annie-howard.com/.

References

Muriel Combes, Gilbert Simondon and the Philosophy of the Transindividual. Translated by Thomas Lamarre. MIT Press, 2012.

Julian Dibbel, ‘A Rape in Cyberspace.’ The Village Voice. December 23, 1993, http://www.juliandibbell.com/articles/a-rape-in-cyberspace/.

Henry Giardina, ‘An Oral History of the Early Trans Internet.’ Gizmodo, July 9, 2019, https://gizmodo.com/an-oral-history-of-the-early-trans-internet-1835702003.

Renee Gladman, ‘Cities of the Future, Their Color.’ The Paris Review, Summer 2018, https://www.theparisreview.org/art-photography/7192/cities-of-the-future-their-color-renee-gladman-edie-fake.

Elizabeth Grosz, ‘Identity and Individuation: Some Feminist Reflections.’ In Gilbert Simondon: Being and Technology, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2013, https://edinburgh.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.3366/edinburgh/9780748677214.001.0001/upso-9780748677214-chapter-3.

Eva Hayward, ‘Spiderwoman,’ in Reina Gossett, Eric A. Stanley, and Johanna Burton (eds) Trap Door: Trans Cultural Production and the Politics of Visibility, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, December 2017, pp. 255–79, https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/trap-door

M.R. Sauter, ‘City Planning Heaven Sent.’ Eflux, February 1, 2019, https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/becoming-digital/248075/city-planning-heaven-sent/.

Georg Simmel, ‘The Metropolis and Mental Life’ in The Sociology of Georg Simmel. New York: Free Press, 1950, https://condor.depaul.edu/dweinste/theory/M&ML.htm.

Sarah Suzuki, ed. Bodys Isek Kingelez. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2018.