In April 2020, I was in my second month of lockdown. The particular state of isolation I was in made my digital life more tangible, and my ‘real life’ intensively more digital. Around that time, TikTok started to gain more popularity and to become a social networking phenomenon which I didn’t delve into until I found out about ‘lesbians on TikTok’ through a discussion on my Twitter feed. TikTok lesbians were talked about as a particular category of both platform users, and lesbians in general, which some perceived as either fun, cringe, attractive, educational and/or just purely fascinating. Driven by that conversation and curiosity it sparked in me, I joined the app and without giving its recommendation algorithm a chance to ‘clock’ me on its own, I started typing #lesbian in the search bar.

Coming to terms with my sexual identity was gravely informed by the processes of seeing and being seen. Having my lesbian identity be invisible to me for the majority of my life, once it was ‘out in the open’ (at least to myself) it motored the desire to constantly witness it in others, as well as to allow for others to witness it in me. Getting on to TikTok to ‘see’ lesbians extended and fused my already established activities of watching lesbian TV shows and films, as well as meeting ‘real-life’ queers, which in the midst of lockdown became possible only through my screen activities. Interestingly enough, one of the first videos that I encountered on ‘Lesbian TikTok’ was the one discussing lesbian (in)visibility in public spaces.

The notion of lesbian invisibility is tied to the lack of lesbian representation on several planes; from personal (which is reflected on in the above tiktok) to legal, social, political, medical and cultural spheres of life. Feminist scholar Annamarie Jagose argues that lesbian invisibility is itself a representational strategy denoting a presence that can’t be seen. The invisibility of the lesbian identity serves to solidify and naturalize heterosexuality, and in itself bears prohibition. Unlike the explicit prohibitive practices that accompany the male homosexual identity, anxieties around lesbian identity are so great that they demand her total exclusion from the social imaginary. Literary scholar Terry Castle connects the gravity of these anxieties to Monique Wittig’s argument that the conception of being a lesbian means denying the traditionally established gender roles imposed by heterosexuality. This refusal consequently undermines the male dominance imposed by heteronormative patriarchy that in turn deals with this threat by making the lesbian invisible and absent.

The first attempts to make the individual lesbian visible were tied to observance of the existence of perceptible difference, which is usually located in non-normative gender expression. In this instance, visibility is equated with visuality. This formulation of visibility, according to Sabine Fuchs, serves as “unconscious metonymy for recognizability” and is itself a limiting notion. The limitation lies in the creation of a system of representation that is narrowly constructed on the account of visible difference that overlooks and marginalizes people that do not make their non-normative sexual or gender identities visually perceptible. Lisa Walker, in her 2001 book The Politics of Looking Like What You Are discusses the ambivalences that surround the feminine lesbian, or the “femme,” that is both privileged and rendered further invisible by ‘passing’ as a heterosexual woman.

In the instance of the lesbian identity on TikTok, visibility as visuality is not located in the markers of perceptible bodily difference that signal the potential lesbian identity of the subject. It is rather formulated through the visible and audible articulation of that identity within the user-generated content. Additionally, it can take shape in a multitude of ways and can encompass the (re)presentation of the lesbian identity in all of its intersectional embodiments. The visuality of the lesbian identity on TikTok thus reflects all its audiovisual presence and representation that is made visible for and by the users themselves through the user-generated content.

NETWORKED IDENTITY OF TIKTOK

What struck me as fascinating while scrolling through my For You feed, was to what extent the lesbian identity became something quite literally performed. TikTok lesbians were engaging in theatrical, narrativized, and stylized performances that served to code their identity as legible, which was either figured through video memes, thirst traps, storytimes, couple videos, and the like.

How the visuality of the lesbian identity (or any identity for that matter) generates on social media, is heavily determined by the platform’s interface and structural possibilities. The platform itself creates its parameters of identity formation and articulation that are further made visible through different channels, for different agents, and different purposes. Jan Hinrik-Schmidt names the identity of users created through social media affordances the networked identity. Networked identity is conceived in accordance with the code that marks both the overall technological infrastructure of the Internet, as well as particular interface formats and affordances of individual platforms. As code pertains to particular affordances, internal structure, and culture of use of a certain platform, the networked identity of TikTok will differ from the networked identity of Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, or LinkedIn.

The networked identity of TikTok is framed through two important interface segments; one refers to the means of expression of users through content creation and the other one pertains to the connective aspects of the platform.

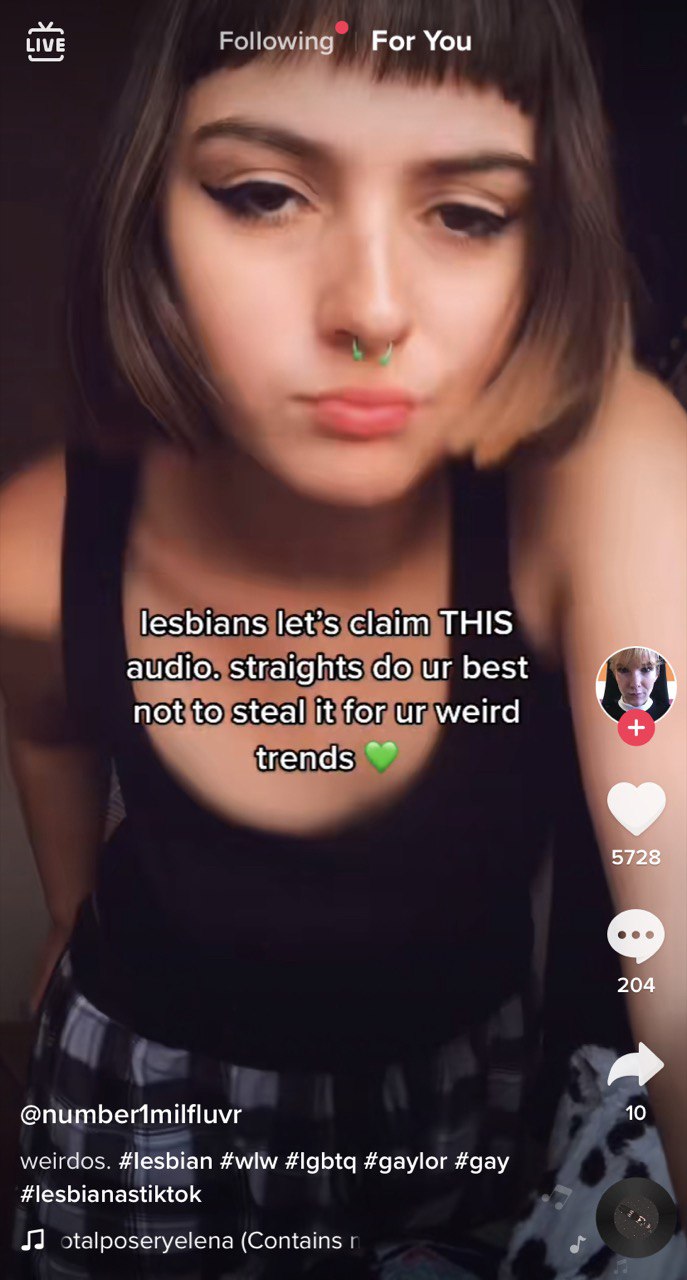

Firstly, the affordances of the platform that are concerned with content creation emphasize users’ performance more than competing platforms. TikTok only allows for the production of video content, supported via a wide range of creative affordances concerned with video editing and the implementation of visual filters. TikTok affords an array of augmented reality filters and effects that interact with users’ faces and bodies, which implicitly puts the physical presentation of the user as a normative instrument in content creation. Strategies in which the users convey the messages in their content through their physicality span from non-narrative bodily performance (prime example on the platform being dance videos), enacting narrative scenes (both by themselves and in a group), talking to the camera, or creating audio-visual memes. The important creative affordance of the platform is its ever-growing archive of sounds and music, which also includes platform-native sounds, that is, the sounds the users have created in their videos. The re-using of the sounds encourages lip-synching, which affirms the norm of performance on the platform. Moreover, it also allows for the proliferation of memetic content, which in turn affirms the cultural and social context of the content creators and consumers. As the sounds can be re-used by a multitude of users, they become a social, or a vernacular affordance, since in some cases certain sounds reflect specific ideas or identity communities on TikTok that appropriate those sounds for individual and cultural expression.

Screenshot of @number1milfluvr's video calling to 'reclaim a lesbian sound' on TikTok.

The importance of sounds in representing an identity community has also been addressed by users themselves. A particular lesbian code emanated from utilizing the songs of queer artist girl in red on the platform. “Do you listen to girl in red?” has become an identificatory question with the same function as the phrase “Are you a friend of Dorothy?” or more recently and more specifically contextualized in lesbian culture “Are you a friend of Ellen?” that serves to identify fellow lesbians.

TikTok’s main content feed, called For You feed, is composed of content that is curated for each user specifically by TikTok’s recommendation system, or in vernacular terms ‘TikTok algorithm.’ TikTok’s recommendation algorithm represents the affordance that is most specific to the platform, which has provoked new ways of both consuming content and creating connections between users. In one of their blog posts, TikTok representatives shed some light on how this recommendation system works, saying that it mostly depends on users’ previous interactions with similar content, their searches, and their location and language preferences. The algorithmic ordering of the For You content feed enables the creation of various communities based on the categorization of the users and their content. Users will often refer to themselves and their content as being part of ‘Lesbian TikTok’, ‘QueerTok’, ‘Spiritual TikTok’, and the like, depending on which filter bubble they think they belong to. To direct the recommendation algorithms to the community on the platform that they wish to participate within, users will opt for using keywords in captions and hashtags, as well as creating content with certain sound bits that reflect their membership to that particular cultural community on the platform. The filter bubbles instituted through the algorithmic connection are often connected to the identity categorizations on the part of the platform, with ‘Lesbian TikTok’ being just one of the many possibilities for the identity-determined communities of TikTok.

Having the identity contextually established through the emergence of the filter bubbles, as well as provided with the possibility to be bodily and narratively performed, created a particular form of expression on the platform. Identity becomes one of the main centers around which the content-creation is formulated that in turn takes shape through users’ creative and bodily performance. In that sense, the networked identity of TikTok is not only influenced by the creative affordances that users utilize for their expression, but also through the platform's internal architecture that utilizes the notion of identity to distribute content and organize the environment of its users.

VISIBILITY, PERFORMATIVITY, PERFORMANCE

Given that, in the instance of TikTok, the identity becomes something quite literally performed, it invites a perspective of identity as a performance by Erving Goffman, which is often addressed in discussions on social media instituted forms of identity. Erving Goffman’s theory of self-presentation as performance defines performance as all activity of a person that serves to influence others for a purpose of giving off a certain, intentional impression. Goffman states that the performance is influenced by the ‘setting’ or the scenic parts that influence expression; and what he names as ‘personal front’ which encompass any types of expressive equipment the performer embodies, such as gestures, facial expressions, physical characteristics, clothing, speech patterns and the like. Social media platforms thus create the setting within which users perform their identity and construct a personal front through the segments of the interface that enable self-definition and expression. That is usually done by choosing a username, profile picture, and posting content. An important facet of this theory is that it is always context or audience-dependent, meaning that they usually shape the nature of the performance in terms of its appropriateness and desirability. In that sense, Goffman’s notion of identity performance applies to TikTok’s content-creation even more so than other platforms, as it is heavily audience and context-dependent and it encompasses bodily and behavioral enactment of that identity on the part of the creator.

When discussing the notion of identity performance, it is necessary to complement Goffman’s perspective with Judith Butler’s notion of identity performativity, as they are both reflective of the identity-forming and presenting practices on TikTok. Goffman’s notion of performance refers to any type of bounded act of the performer that is aimed at conveying a certain impression, with the performer consciously utilizing all the signifiers at their disposal, of the identity they want to put to the front. Judith Butler’s theory of gender identity, but also of identity in more general terms, relies on the concept of performativity, which, unlike Goffman’s theory, diminishes the agency of the subject/performer in constructing their own identity. Butler’s notion of performativity seeks to explain how categories of identities are made visible in discourse through imitative performance. The difference between performance and performativity is that performance is a singular, bounded act, whereas performativity refers to “a reiteration of a norm or a set of norms” through repetition and imitation of speech-acts, bodily gestures, and the like, which serves to consolidate those norms within identity categories, as well as to make them legible and valid as such.

In such a way performativity constructs the discursive identity categories through the reiteration of the legible markers of these identities. This, in turn, legitimizes both the subject as being something, as well as the identity category, which is simultaneously naturalized and essentialized by the process. This perspective opposes the idea of the identity being something internal that comes to light through individual expression and rather takes an opposite position in which the external norms of (self)definition are internalized through performance. Because the norm is so contingent on performativity, it is rendered unstable, as it needs to be made and re-made constantly, and in that instability lies the potential for the subversion of the norm, especially in situations in which the dominant version of the performance ‘fails’.

The performativity of TikTok serves to provide distinct self-expression that is platform-native and is informed both by the platform’s architecture and affordances and the users’ interpretation of that setting and their contribution in creating their own norms in content creation and consequently dissemination of the lesbian identity. TikTok’s interface facilitates both the performance and the performativity of the lesbian identity, as on the one hand users are opting for tactics of self-presentation and impression management in Goffman’s sense; and on the other, the segments of interface used for content creation facilitate users’ engagement through acts of repetition, imitation, and citation whilst performing the lesbian identity. Additionally, imitation and citation processes are entailed in content making trends on the platform in which the articulation of the identity or the message in the content is standardized by the users and uplifted by the platform through popularizing it via content distribution, most commonly through the medium of memes.

DISCOURSE/ THIRST TRAPS/ INFORMATION

Even though I noticed the tendencies of users to uniformly perform the lesbian identity, the visibility of the lesbian identity in the user-generated content manifested itself in different shapes and forms, and for different purposes. Some of the videos I’ve seen strangely validated my experience that I took as extremely individual beforehand, which in turn affirmed the cultural aspect of my identity that still remained deeply personal. Lesbian identity was something that was defined and dissected also in comparison, juxtaposition, and intersection with other identities in the LGBTQ+ community, as well as ones out of it, such as the ones of class, race, age, profession, or otherwise. At a certain point, I also felt stifled by the overrepresentation and some of the narrow definitions of the lesbian identity I might have come across.

One of the most prominent forms of lesbian representation on the platform is a thirst trap. Thirst trap is a colloquial name for the digital images users post on their social media accounts that enact the seduction and put the sexual identity of the user to the front. This form is not confined to the lesbian community, and has its roots on platforms other than TikTok, but has instituted itself as one of the most prominent ‘lesbian genres’ on the platform. In these videos, the users usually present their bodies and gestures alongside a song with the sole purpose of sexualizing themselves for the viewing pleasures of other lesbian users. The portrayal of lesbians in mainstream media often features sexualized images of lesbians, which according to Karen Hollinger fuel homophobia since they are geared towards the representation of lesbians as pornographic sexual objects intended for male audiences. In the instances of thirst traps, the self-sexualization is often conducted by lesbians that display non-normative femininity, which differs from mainstream representation in which the sexualized lesbians are most commonly presented as hyperfeminine. Whether the lesbian thirst trap is created and posted by a feminine or a masculine lesbian, in either case, this type of video focuses on the segments of the lesbian identity that represent desire, pleasure and seduction, seeking to reclaim these aspects of the lesbian identity in aims of dislocating it away from dominant representations that cater to heterosexist standards.

The interplay of gazes in this instance is significant, given that the sexualization of women and lesbians, and the subsequent objectification of them via the ‘male gaze’, renders women without agency, which amplifies the social state in which, in the words of John Berger, “men act and women appear.” Laura Mulvey’s account on the attribution of the look in mainstream cinema aligns with the power relations between men and women, in which the woman is usually framed as the object of desire, whereas the man represents an active agent and pursuer, the bearer of the look. The gaze of the film camera and subsequently the spectator align with the look of the male protagonist, framing the classical Hollywood film experience through the lens of the male gaze. Hollinger discusses the possibility of the lesbian spectator that disrupts the heterosexual distribution of the gaze and is being empowered through becoming an active desiring female subject. As the lesbians engaged in creating ‘thirst traps’ use the selfie medium to create the videos, they are framing themselves as both the subject and object of desire. They seek to indulge the lesbian gaze, which is in this instance mediated through the algorithmic gaze of the platform, one that is further motorized through the utilization of affordances such as hashtags and captions that seek to algorithmically identify the content and deliver it to the intended audience.

Apart from posting thirst traps, filming couple videos, or creating audiovisual memes, TikTok users are also using the content-creation affordances to engage in discourse concerning lesbian identity and experience. In his 1969 book The Archaeology of Knowledge, Michel Foucault identified discursive formation as all the statements that refer to the same object, however formally different they might be, or temporally dispersed.

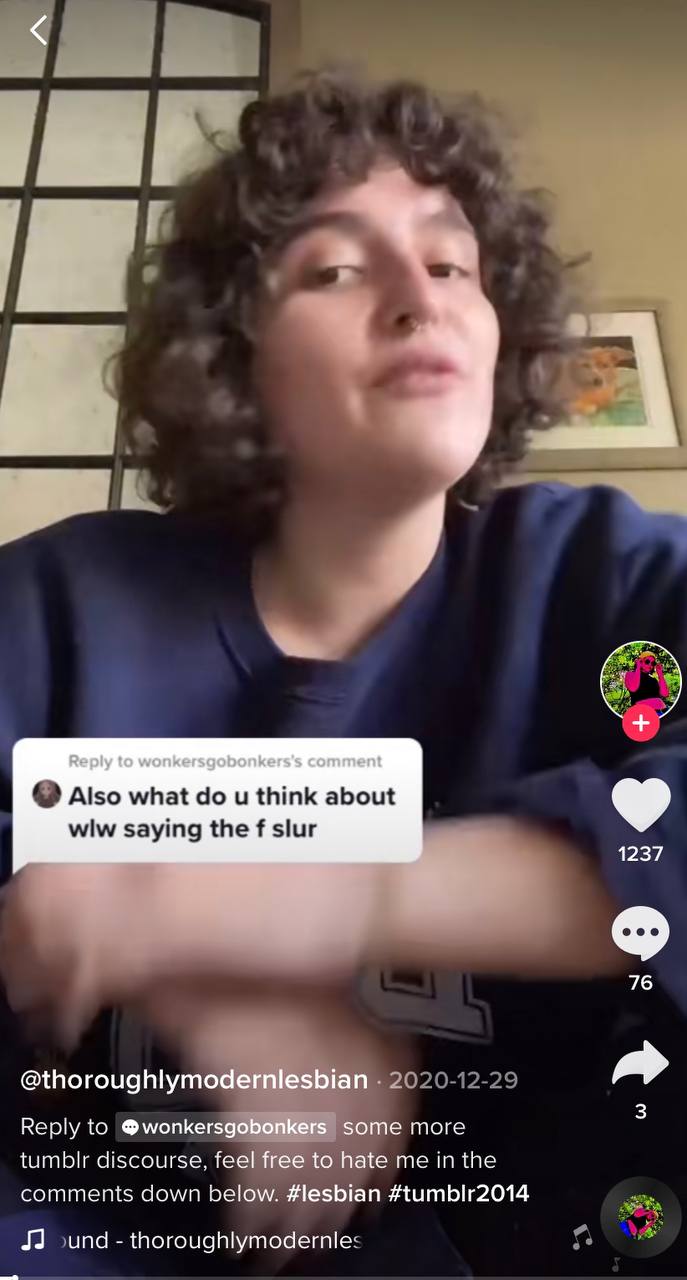

All content on TikTok referring to lesbian identity can be grouped under the same discursive formation, however, the type of content discussed here approaches discourse in more straightforward terms than the other forms of content concerning the lesbian identity. Namely, the users themselves are categorizing these videos as ‘discourse’ videos and the videos are often tagged with the #discourse hashtag in order to be recognized as such more easily. These videos are usually filmed with a selfie camera and contain a person vocally elaborating on a given subject regarding lesbian identity. The affordance of ‘stitching’ is often used in these types of videos, as it provides a counter-reaction to some other discourse video and invokes a dialogue on the platform. Another affordance that is pertinent to this type of content is the affordance of users being able to reply to comments on their videos with a video reply, in which the comment is visible on the screen.

Screenshot of @thoroughlymodernlesbian's video on lesbian discourse.

Ananda Mitra and Eric Watts approach internet-mediated discourse through the notion of voice which serves to articulate the particular form of agency users acquire in positioning themselves within the discursive space of the internet. The notion of voice is ideologically usually connected to the margin, as the center is often represented as ‘voiceless’ since it is normatively dominant. They note that the internet represents an ambiguous, hyperlinked environment, in which the center is hard to locate, and as such provides marginalized communities with an opportunity to voice their opinions and positions in a more egalitarian way. In order for the voice to be actualized as an event, it needs to become “an answerable phenomenon”, that is to be heard and acknowledged.

In the case of discourse videos on TikTok, the notion of voice becomes literal, as the actors are verbally voicing their opinions and feelings through their vocal agency. The voice, apart from presenting a symbolic instrument of power, aligns with the physical voice of the speaker in which the discursive utterance acquires a face and a name. Mitra and Watts note that, on the Internet, the power of the speaker is represented through their eloquence, rather than a spatial position from which they are speaking. Through the options of stitching and video-replying to comments, the speakers are situating themselves in dialogue that in turn actively produces a discursive community through “utterances and their reception.” In the case of video replies to comments, the speakers are enacting greater discursive authority through physically embodying the voice that contradicts the given statement and by providing themselves with greater expressive space to articulate their position. They are making themselves even more present to the world than the (in some instances even anonymous), commenter. The discourse videos encompass a variety of topics, such as the issue of intersectionality in lesbianism that elaborates race, class, ethnicity, and gender identity within the lesbian community, the differences and disputes of lesbians with other sexual minorities, as well as ‘the proper definitions’ of the lesbian. Through these videos, the lesbian identity becomes a site of dispute and reckoning, and a myriad of voices can be heard; some of which serve to gatekeep the lesbian identity, some of which tend to leave the label as open and insubstantial as possible. In this way, users are actively engaging in defining the lesbian identity on their own terms, and the plurality and multitude of the lesbian identity is put forward through many disagreements and nuancedly provided elaborations.

Seeing something also makes something known. Given that the lesbian identity and the cultural currents it encompasses often fly below the radar of the mainstream culture, the knowledge of its (inter)personal, political and cultural potential, still represents a sort of secret knowledge for many people, hidden below the dominant norms of hetero-patriarchal society. Some TikTok users utilize the instrument of visibility to disperse information that becomes valuable for others in both their personal and political activities.

Cait McKinney identifies information activism as the type of lesbian feminist activism that is formed around information gathering and distribution, for purposes of providing resources to lesbians in terms of their personal lives, keeping up with the social movement, and maintaining the historical continuum. Information activism is based around the available technologies instrumentalized to mediate and shape the relationships within feminist movements.*

One particular trend that was significant on the platform was the circulation of the “Lesbian Masterdoc” which is a document created by one of the users that contains self-reflexive questions aimed to help other people figure out if they are a lesbian, unaware of their sexuality due to compulsory heterosexuality. In this instance, visibility of the lesbian identity takes shape through the information that serves as an instrument aimed to aid the articulation of the individual lesbian identity, to help enrich and facilitate the lesbian experience, as well as to foster a sense of community by providing users with a sense of shared history and culture.

VISIBILITY BY THE ALGORITHM

I, myself, haven’t been posting any content on TikTok and have been using the app solely to watch and consume what others have been creating. As I grew up with social media platforms, they have been very influential on my personal identity construction and reflection, but TikTok might have come too late in terms of the formative effects it could possibly have on me. Engaging with creative video performance and allowing it to be dispersed to an anonymous audience, placed the emphasis on the vulnerability that comes with visibility which, in my case, was also configured through a very foreign form of expression. However, even though I have been ‘passively’ using the platform, my lesbian identity was still very much visible to it.

Apart from visibility being figured as visuality, as Sabine Fuchs notes, visibility might be formulated as knowability, quoting Rosemary Hennessy:

“[t]he ‘visibility’ of these issues is not a matter of what is empirically 'there' ..., but of the frames of knowing that make certain meanings ‘seeable.’”

Amy Villarejo mentions visibility formulated by a mutual recognition between queer people and lesbians, colloquially referred to as “gaydar”. This type of perception alludes to suggestion, the elusive quality, or qualities, of being gay, that fly under the radar of common perception. ‘Gaydar’ thus indicates alternative ways of perceiving and being perceived, but is limited to the lesbian and queer communities that develop particular means of recognition based on shared identities and experiences, and is presumed to be unavailable to the individuals outside of these communities. The tiktok shown at the beginning of the essay similarly ponders the notion of knowability framed through the instrument of ‘gaydar’. However, in the case of TikTok, gaydar acquires the technical properties its name originally figuratively implied and transposes it into literal machinic recognition of queerness.

As was mentioned earlier, For You feeds of users are organized through algorithmic mediations of the platform that serve to connect the right users to the right content through their perceived similarity. In order to curate a perfect For You feed, TikTok collects data by tracking users’ seemingly passive utilization of the platform.

By scrolling through their For You feeds, users are engaging in intensive watching and seeing, while simultaneously being watched and interpreted back by the platform as being something. In this process, they are assigned what John Cheney-Lippold named an algorithmic identity, which represents a digital identity formation composed of algorithmic interpretations of user’s data that in some instances might not at all correspond to the user's real-life identity or self-perception. Algorithmic identities are based on the collection of users’ online behaviors which are then interpreted by the algorithm as belonging to a particular identity, usually through ‘matching’ with the group that displays similar online behaviors. Apart from offering identificatory pleasures to the users by providing them with the content that corresponds to their identity, this type of algorithmically mediated identity and its subsequent visibility is based on dataveillance. Dataveillance is a type of surveillance instituted through the gathering of data and subsequent classification of populations into categories and groups, that in the platform environment, usually has the function of providing unified target groups for advertisers. In the case of TikTok, it also marks the main instrument of overall platform organization, individual user experience, and interpersonal connection-forming.

Visibility by the algorithm, or the algorithmic gaze that emerges in this process, undoubtedly influences user subjectification by providing the users with mediated images of themselves. The algorithmic image is not visual, as it is composed of data, but through other providers of visuality on the platform, the image that is reflected back to the user has sound, vision and options to like, comment, and follow. Additionally, through the algorithmic gaze, the platform is organized and regulated by creating common spaces and controlling who gets to occupy them.

However, it is important to note that algorithmic interpretations and constitutions of identities are not rock-solid and unchangeable, as they are exposed to constant change and challenges as the user offers new data that might contradict the old. For example, if a user that is classified as a lesbian on the platform stops interacting with lesbian content, she might get less and less of that content and will, in turn, become invisible to the platform as such. This type of visibility is also somewhat determined by conscious user’s actions, as they make themselves visible through their usage of the platform that directly or indirectly signals their lesbian identity.

Visibility by the algorithm represents a form of panoptic surveillance, rudimentarily marked by the concept of the few watching the many, in which the platform has a role of a surveillant that watches and subjectifies users. This type of surveillance makes the user seen as ‘being something’ that further impacts the new form of self-identification instituted by the platform. The algorithmic gaze of TikTok has also facilitated the phenomenon of being ‘outed by the machine’ as some users reported they have come to terms with their homosexual desires through being shown the lesbian content on their For You Feed.

The logic of surveillance capitalism, according to Shoshana Zuboff, is based on ‘fortune-telling’ and 'selling’ which amplifies the anticipatory nature of algorithms which is being directed at modulating users’ behavior toward what brings the platform and the advertisers the most profit. Through surveilling the users and gathering their data, the recommendation algorithms are in a constant game of guessing what the users might be and what they might want, to which they respond by providing them with the content that aligns with those speculations. In this sense, surveillance not only brings confirmation of the lesbian identity of the user but makes the lesbian identity a speculative category that might prove itself to be true or false. This process further emphasizes the innate invisibility of the sexual identity as such, as well as its commodified nature in the platform environment.

Moreover, this type of surveillance is made explicit by users themselves, through the content that is aimed at ‘outing’ the end-user as being lesbian or queer. In some cases, through presuming and outing the identity of the end-user, the content-creator also encourages them to interact with the video, as well as otherwise connect to the user by messaging or following them.

Apart from this practice representing joint surveillance of the content consumer from the end of both platform and content creator, it also entails components of sousveillance, that literally translates as watching from below. Sousveillance practices are aimed to turn back the instruments of surveillance to the ones in power, as Mann et al. put it, representing an

“act of holding a mirror up to society, or the social environment [that] allows for a transformation of surveillance techniques into sousveillance techniques in order to watch the watchers.”

By ‘outing’ the end-user through this content, the content-creator is also ‘outing’ the algorithm that is presumably a hidden affordance of the platform, making the surveillance conducted by the platform explicit, and in this case, something that can be used as a creative strategy in content creation. This practice in content-creation reflects a unique relationship of users to surveillance, which makes surveillance acknowledged and accepted as a mundane aspect of their social media experience, as well as utilized for their own benefit, whether as a creative component or as an instrument of connection to other users.

SEE ME, SELL ME, BUY ME

Even though I was quite amazed by the amount of amateur content that made the everylesbian visible, the videos I would be getting on my For You feed were mostly the ones with at least a few thousand likes with some of the ‘prominent lesbian and WLW tiktokers’ being a regular spectacle on my daily TikTok scroll. On TikTok, everyone could aspire to their 15 seconds of fame, but chances that they are getting it, depend on the complex intertwinement of platform governance and user engagement. The setting of the platform works more like a narrow-cast digital television, than a social network aimed at forming tangible connections between users, which puts higher stakes on vulnerability that comes with visibility. That vulnerability sometimes seeks to be ‘paid off’ through acquired popularity on the platform. In other instances, visibility might even make the content-creator vulnerable to the extent of being bullied and harassed, in which the creator seeks to limit it to the communities and users that provide a safe environment for expression.

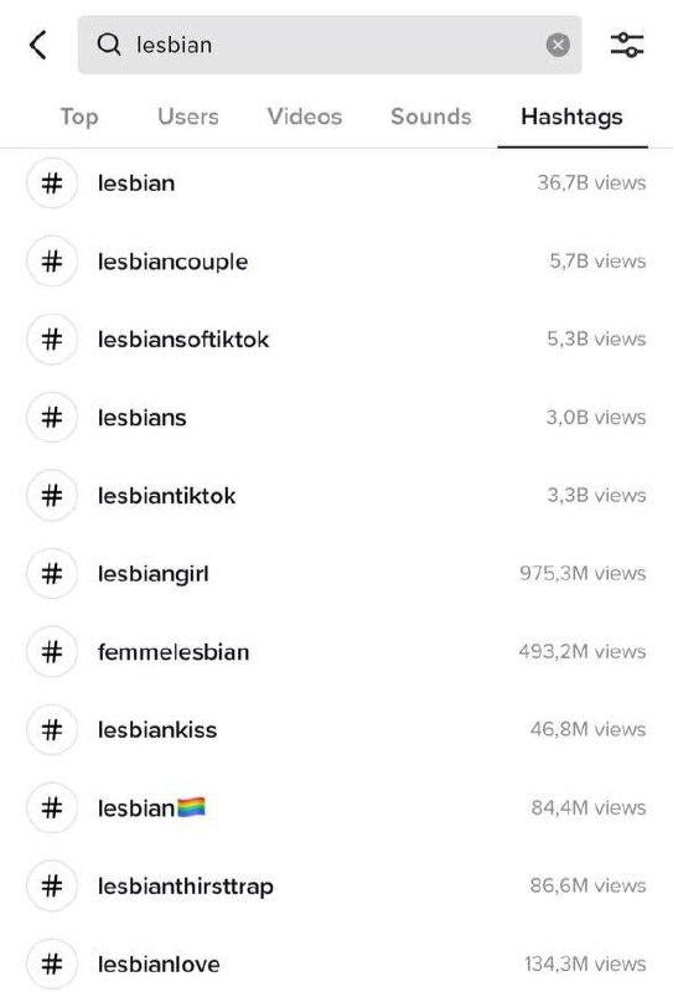

In digital environments, the notion of visibility is often equated with the quantified presence of and engagement with the content on a given platform. Content creators can use the affordances of captions and hashtags to tag their content and address it to the right audience (e.g. lesbian content is most often captioned or tagged with words such as #wlw, #lesbian, #queer). Through utilizing specific hashtags that denote both the character of the content, as well as the intended audience for it, the users make their content ‘algorithmically recognizable’ in hopes that the recommendation algorithm will deliver it to the right viewers. Moreover, users can opt for using trending or popular hashtags, as well as the #fyp hashtag with the goal of reaching a broader audience and going viral on the platform.

Hashtag in this instance presents an affordance that takes the function of generating visibility of the lesbian identity on the platform, as it serves to make content recognizable both to the algorithm and the other users as being lesbian. However, users have noticed the tendency of the platform to censor the content tagged with the hashtag #lesbian, because it recognizes the word as denoting a pornographic category. This example illustrates that the platform ultimately holds the power in attributing meanings to hashtags as affordances for visibility and consequently enables and disables for that visibility to take place in its environment. As a resistance strategy, the users have created a hashtag #le$bean that serves to bypass the censorship imposed by the platform misinterpreting and policing content that depicts lesbian identity. This event marks the enactment of the power struggles and negotiations concerned with naming and showing the lesbian on TikTok, given that even though it is widely enabled on the platform, it still represents a site of contestation and unfavorable meanings attached to it.

Content creators searching to increase the visibility of their content on the platform are involving themselves in certain negotiations with the algorithm in order to achieve this goal. In this way, the algorithm exists not only as a hidden affordance but also imagined through a lens of economic relations on the platform. The tactics content creators employ are heavily based on their own interpretations and speculations of what the most successful strategy would be in order to engage the algorithm to be ‘on their side.’ Kelley Cotter suggests that these negotiations can be regarded as “playing the visibility game” that social media influencers engage in to make themselves and their content more widely distributed and known among other users. As players in the game, the influencers approach the platform and its organizational processes enacted through the algorithmic distribution of content, as something that they can master for their benefit. The attention economy instituted by social media platforms regards visibility as a reward and a lucrative endeavor for individuals looking to monetize their online popularity.

As users fashion the lesbian identity as a commodity to be popularized across the platform, they indulge in self-commodification as much as in the articulation of the self. Rosemary Hennessy discusses how the visibility of sexual identities, both normative and non-normative, could not be separated from the economic and material circumstances that intersect with social and cultural norms and modes of being. In this account, she steps away from the notion of ‘authentic sexual orientation’ to understand how

“the ways sexual (as well as other) desires and identities are historically organized or how gendered sex-affective relations are infused with ideologies of race and mediated by relations of labor.”

In her analysis, she notes that the lesbian identity is produced as a commodity that is being fetishized through its inscription in the capitalist dominant modes of intelligibility, which aims to conceal the system of social relations that ultimately produce it. In the instance of TikTok, the lesbian identity takes on a commodity nature by being presented in a form of a video that is often produced through uniformizing standards of the trends that sweep the platform.

Additionally, the overall content creation on the platform entails the questions of free labor that help shape the distinct form of expression that is later capitalized on, provided by the users both through UGC and usage of the platform. As Mark Andrejevic puts it:

“The form of labor in question tends to be “free”: both unpaid (outside of established labor markets) and freely given, endowed with a sense of autonomy. The free and spontaneous production of community, sociality, and shared contexts and understandings remains both autonomous in principle from capital and captured in practice by it.“

The advertisements featured on TikTok are getting harder to distinguish from non-sponsored content, namely an ad for the lesbian dating application HER is created as a user-generated video, using the form and imagery instituted by the platform by being created in the form of UGC by actual, popular TikTok content creators. This example illustrates how the affective and immaterial labor of users to generate “networks of sociability, taste, and communication” is being exploited to produce valuable forms that are later utilized for marketing and profit-making purposes by advertisers. Moreover, through appropriating user-generated forms for marketing purposes, the platform manages to equate the personal and communal user expression to a literal commodity form, making one almost indistinguishable from the other.

HER ad on TikTok.

WHO NEEDS VISIBILITY?

After more than a year on TikTok, which was marked by extensive processes of both being seen and seeing, I felt a certain consolidation of my identity which was in equal parts validating and confronting. These events enabled the individual, cultural, and social processing of a subjectivity, as well as a personal and political practice, that requires its visible and undeniable presence to be acknowledged. Having control over one's visibility is important in empowering marginalized individuals and communities, however, visibility should be taken as an instrument, rather than an end-goal.

“Can the visibility of identity suffice as a political strategy, or can it only be the starting point for a strategic intervention which calls for a transformation of policy?“

Judith Butler, 'Imitation and Gender Insubordination'

‘Lesbian TikTok’ represents a contemporary social media formation that instilled itself in the continuum of the relationship between lesbian identity and visibility, which provided for novel perspectives on these notions and ways in which they relate to each other. The multiple facets of visibility in this instance manifest the complex interplay of gazes and agencies in being and making something or someone visible online. In that sense, the notion of visibility is inextricable from surveillance practices that became pervasive and elastic through the digitally instituted sociality. Additionally, it is influenced and utilized by economic processes on the platform that either encourage the attempt for popularity that can be lucrative for both content-creators and the platform or serve to produce the content consumer as part of a visible and marketable target group.

As an ambiguous term, visibility takes many shapes and meanings and makes for both potentially exploitative and empowering uses. In the instance of TikTok, it represents a category that cannot be subdued, if one wishes to engage at all in interaction with the platform and other users that share their social and cultural background. Moreover, developing a relationship to visibility means involving oneself in constant negotiations, and sometimes compromises, about what should and in what way be seen and shown. As visibility on TikTok is always created within the code instituted by the platform, as well as used by the platform for its own particular economic and governing purposes, it unquestionably becomes a tool of power that can be utilized in different ways. Acknowledging visibility without limiting its potential solely to its representative uses, enables critical engagement with this notion and subversive employment of the possibilities it provides, particularly within digital environments we almost have no other choice but to inhabit. I’m curious to see how we continue to get there.

FOOTNOTES

*Emma Holler does a more in-depth comparison of lesbian information technologies to TikTok that draws resources from McKinney’s book in this article: https://aninjusticemag.com/tiktok-as-a-tool-for-navigating-the-lesbian-lexicon-74f5d839e1be.

REFERENCE LIST

Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, New York: Routledge, 1999.

Judith Butler, ‘Imitation and Gender Insubordination’, in: Henry Abelove et al. (eds), The Lesbian and Gay Studies Reader, New York: Routledge, 1993, pp. 307-320.

Terry Castle, The Apparitional Lesbian: Female Homosexuality and Modern Culture, New York: Columbia University Press, 1993.

John Cheney-Lippold, ‘A New Algorithmic Identity: Soft Biopolitics and the Modulation of Control’, Theory, Culture & Society 28.6 (2011): 164–81.

Michel Foucault, The Archaeology of Knowledge, New York, London: Routledge, 2002.

Sabine Fuchs, ‘Lesbian Representation and the Limits of "Visibility”’, In I. Härtel et al. (eds.), Body and Representation, Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien, 2002, pp. 43-49.

Kelley Cotter, ‘Playing the Visibility Game: How Digital Influencers and Algorithms Negotiate Influence on Instagram’, New Media & Society 21.4 (2019): 895–913.

Erving Goffman, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, New York: Anchor Books, 1969.

Karen Hollinger, ‘Theorizing Mainstream Female Spectatorship: The Case of the Popular Lesbian Film’, Cinema Journal, 37.2 (1998): 3-17.

Rosemary Hennesy, Profit and Pleasure: Sexual Identities in Late Capitalism, New York: Routledge, 2000.

Annamarie Jagose, Inconsequence: Lesbian Representation and Logic of Sexual Sequence, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2018.

Cait McKinney, Information Activism: A Queer History of Lesbian Media Technologies, Durham, London: Duke University Press, 2020.

Ananda Mitra and Eric Watts, ‘Theorizing Cyberspace: The Idea of Voice Applied to the Internet Discourse’, New Media & Society 4.4 (2002): 479–498.

Laura Mulvey, ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’, Screen 16.4 (1975): 6-18.

Jan-Hinrik Schmidt, ‘Practices of Networked Identity’, in: Hartley, J., Burgess, J. & Bruns, A. (eds), A Companion to New Media Dynamics, Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013, pp. 365-374.

Lisa Walker, Looking Like What You Are: Race, Sexual Style and the Construction of Identity, New York: NYU Press, 2001.

Amy Villarejo, Lesbian Rule : Cultural Criticism and the Value of Desire, Durham: Duke University Press, 2003.

Shoshana Zuboff, ’The Secrets of Surveillance Capitalism’, Frankfurter Allgemeine, July 17 2019, p. 5.

Steve Mann, Jason Nolan, Barry Wellman, ‘Sousveillance: Inventing and Using Wearable Computing Devices for Data Collection in Surveillance Environments’, Surveillance & Society 1 (2002) 3, pp. 331-355.

Mark Andrejevic, ‘Social Network Exploitation’, in: Zizi Papacharissi (ed.), A Networked Self Identity, Community, and Culture on Social Network Sites, New York, London: Routledge, 2011, pp. 82-101.