“How happy is the blameless vestal's lot!

The world forgetting, by the world forgot. Eternal sunshine of the spotless mind!” Alexander Pope, Eloisa to Abelard

“We rip out so much of ourselves to be cured of things faster than we should that we go bankrupt by the age of thirty and have less to offer each time we start with someone new. But to feel nothing so as not to feel anything—what a waste!” Andre Aciman, Call Me By Your Name (2017)

“…

and say, sit here. Eat.

You will love again the stranger who was your self.

Give wine. Give bread. Give back your heart

to itself, to the stranger who has loved you” Derek Walcott, @ Joseph Fasano op X Today’s poetry thread BREAKUPS on twitter

“所以我突然明白了一个道理,这段感情里,原来我们势均力敌,结尾处统统惨败,我毁掉的,是他关于我的这个梦想; 而他欠我的,是一个本来承诺好的世界。” 鲍鲸鲸,失恋33天

“As time has gone on, I fall less and less in love with him but he still lingers in the back of my mind. I’ve dated new people, slept with people, but nothing comes close to what we had. I hope I find that again one day, just not with him.” Anonymous, Museum of Broken Relationships

Smartness and Pain

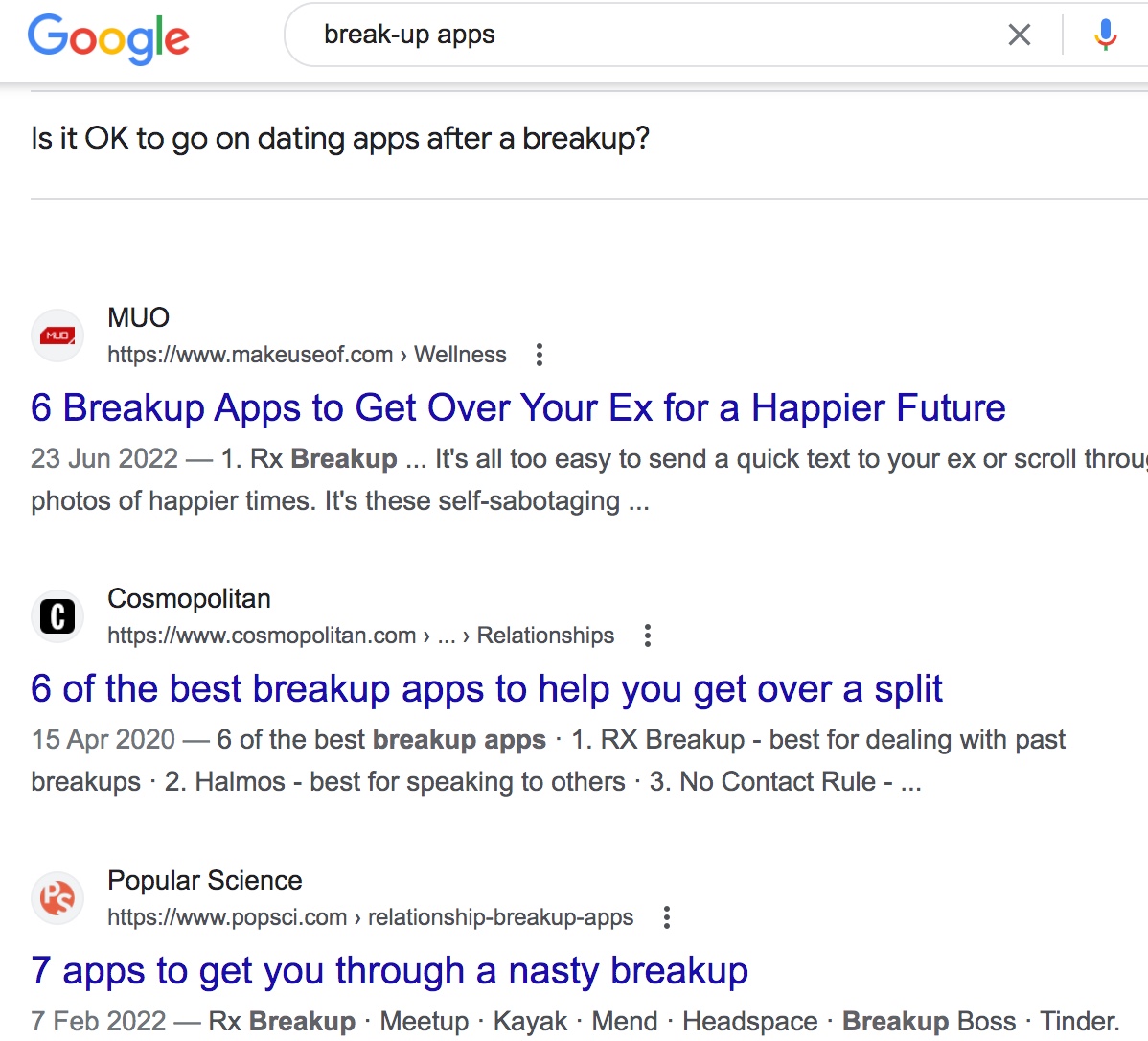

Whenever I tell friends and strangers I study break-ups, they wonder if I am a psychology student. I‘d say no and tell them I relate break-ups to cultural objects such as break-up apps. They respond differently, but most of them pause for a second. “Hmm, break-up apps…” I see the question marks on their faces. Do they really exist? How do such apps work? And why should one care?

Yes, break-up apps exist, but they are way less known compared with dating ones. Based on a 2023 marketing analysis from FinancesOnline, a U.S. platform for software and financial product reviews, approximately 1,500 online dating sites and apps exist worldwide (see also data from bedbible.com). By contrast, there are just 10 options for break-up apps in the Google Play store (determined by using an app store crawler tool made freely accessible for education purposes by my UvA Media Studies teacher, Esther Weltevrede from my elective course Appification. The number of Chinese break-up apps from Yingyong Bao (应用宝) - an app store run by the tech company and media giant Tencent that I analyzed in an earlier course paper - is also 10. Then there are meditation apps like Headspace, which has a program for break-up help, and Mend, a start-up company that has developed an app for break-up training. Since the space for this writing was provided by the “data-free” Institute of Network Cultures, I will not use data-oriented tools to map the break-up apps in the digital landscape. Instead, I will give priority to concepts, theories, stories and reflections.

Questioning the existence of break-up apps draws attention to the status quo that break-up apps are overlooked. There is a gap between dating apps and break-up apps. Even though not all gaps have to be filled, there is theoretical value in this gap in academia. A rudimentary search with the keyword ‘dating apps’ shows many articles on dating apps published in journals, including in Computational Culture, Media, Culture & Society, Computers in Human Behavior, and Journal of Sociology (Melbourne). However, after digging into databases, I found only one study from 2015 concerning break-ups, titled The Role of Facebook Use in Mediating the Relation Between Rumination and Adjustment After a Relationship Breakup. The study mentions the behavior of deleting messages and concludes that the principle “out of sight out of mind” seems to offer comfort. Breaking up on the internet implies acts such as deleting accounts of ex-partners, and unfollowing or blocking them. This links to the tactic of ghosting, which relies on technologies, especially social media, for “not responding to phone calls or WhatsApp messages, ceasing to follow or blocking social network sites.”1Caitlyn Kay and Erin Leigh Courtice, ‘An Empirical, Accessible Definition of “ghosting” as a Relationship Dissolution Method.’ Personal Relationships 29. 2, (2022): 386–411, https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12423, pp. 388.

Will it be possible to think of break-up app theory in ghosting? It depends. Even though ghosting is considered a relatively new phenomenon in the intersecting studies of relationships and communication, it has already been around in humanities, considering the work of Jacques Derrida, Mark Fisher and another UvA teacher of mine, Esther Peeren. The potential to take ‘break-up theory’ in the direction of ghosting enables us to imagine how social media can be used for breaking up, but sadly without breaking away from the already dominant communication tools. This line of thinking will also not guide attention to a discussion of what break-up apps can do.

Some time ago I liked a guy who did not like me back and broke up with me no matter how hard I tried to repair the relationship. It is what it is now. I’m not blaming him for the break-up, and I thought of what I had not done well in the relationship, too. Breaking up was hard to do because ending a relationship is not the end of the work. I needed to actively work to bring closure to find peace.

Making an issue out of the phenomenon of break-ups is definitely not revenge on my ex-partner - it started as my automatic response to pain. It was intuitive. I watched break-up films in the hope of learning from them. I wanted to have clarity and move away from the chaos. It is a fantasy to outsmart the pain of heartbreak. In simple words, I fought by learning. I had the question: how can I move on from my post-breakup attachment which was so sticky-tricky? As emotional disturbances arrived, I wanted to withdraw from love, to detach, disconnect and disengage, but the question is how?

Many may mistake the idea of moving on for hating the ex-partner, for making the person disappear and killing the pain. No matter how one learns to outsmart the pain, outsmarting the pain is not all wise. At least in English, the word ‘pain’ is historically linked to smartness. The American cultural theorist Lauren Berlant wrote in their book Cruel Optimism:

“The intellectual referent of the word ‘smart’ derives from its root in physical pain. Smartness is what hurts, or to say that something smarts is to say that it hurts—it’s sharp, it stings, and it’s ruthless. It is as though to be smart is to pose a threat of impending acuteness (I.. actus — sharp).”2Lauren Berlant. Cruel Optimism. Duke University Press, 2011, pp. 139.

This is a less quoted text but it is thought-provoking. Given that ‘smartness’ comes from pain, knowledge may be indistinguishable from pain - a little reflection on my situation. Since learning was the way I was thinking to get over the heartbreak, what I learned first was unexpectedly painful later. I remembered that I wanted to start over. The broken relationship would be fixed if I learned how to rekindle the romance. On YouTube, there are endless instructional videos from life coaches on giving a relationship another chance. Without shame, I admit that I binge-watched them one after another. The content ranges from how the brain of an ex works after a break-up to what to say exactly when an ex wants to be friends (but the other secretly doesn’t want to). If my ex ever knew it, he might assume me as a smart-ass. After all, love is not a military battle of winning someone over with internet strategies. From this perspective, this interconnection between pain and smartness could mean that my smartness would become an unwanted force nudging an ex to change their mind.

Berlant’s reading of Mary Gaitskill’s novel Two Girls Fat and Thin offers another important perspective. They point out that the “counter-traumatic effects of smartness” that the two protagonists seek are almost the same as “traumatic effects”.3Ibid. I would not open a can of worms here to relate break-ups with trauma to think of how to live through them. But for many, break-ups do not automatically bring closure. The aftermath could be experienced as “traumatic” in some cases, which is why some interpersonal communication scholars focus on well-being and satisfaction in the post-dissolution period. Do not expect my discussion of break-up apps to add to the discussion around trauma, even though the introduction touches upon this word.

Berlant sensed that counter-trauma attempts could be traumatic. When I researched the film Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, which tells the story of memory-erasing after a fight between the main couple Clementine and Joel, I stumbled upon the book Trauma and Memory by Dr. Peter A. Levine – a psychotherapist who invented the method of “somatic experiencing”. While as a cultural analysis student I may not agree with all his interpretations of the film, I do see the counter-productive nature in the root of the word ‘smart’ again in this context.

In a New York Times article titled After PTSD, More Trauma, a veteran named Morris gives an intimate account of how harmful his therapy sessions were. Levine follows up on this account in an epilogue to his case studies, by arguing that a certain form of talk therapy is not for everyone. He cautions that by making the clients re-tell the unfortunate occasions, stress may increase out of control. Another German verb abreagieren helps to understand this drama from counter-trauma to more trauma.

Abreaction – derived from the German word Abreagieren – refers to the reliving of an experience in order to purge it of its emotional excesses. The therapeutic efficacy of this has been likened to ‘lancing a boil.’ Piercing the wound releases the ‘poison’ and allows the wound to heal. In the same way, the lancing process is painful, reliving the trauma can be highly distressing for the patient.4Peter Levine. Trauma and Memory: Brain and Body in a Search for the Living Past: A Practical Guide for Understanding and Working with Traumatic Memory. iBooks, North Atlantic Books and ERGOS Institute Press, 2015, pp. 188-9.

‘Smart’ people such as doctors and therapists with advanced knowledge may improperly add to more traumatic experiences after a very distressing experience. Will there be traumatic effects of the counter-traumatic move? If smartness is what hurts, for Levine, it is only the smartness of a talking cure or lancing process that ignores the body, mind, and brain interplay that hurts. Among break-up apps, some intend to be therapeutic. In the following, I will bring in Bernard Stiegler’s notion of the digital as a pharmakon – in Greek, simultaneously a poison and a cure that enriches the thread of thought.

The online etymology dictionary provides a shortcut for understanding the association - it's straightforward. The Middle Dutch word smerten and the German schmerzen are sources of the English word smart, meaning to bite, to hurt, or even to cut. This matters to my encounters with cultural objects related to break-ups, including apps. In my desire to know how to move on after a break-up, I will bring up the connection between smartness and pain again, but differently this time.

Allow me a far-fetched but very vivid example – the 2022 indie sci-fi film Everything Everywhere All at Once that turns a family drama of Chinese-Americans into a bizarre but moving and comic, multiverse-jumping action fantasy. One specific image helps me make sense of this linguistic coupling between smartness and pain. It pictures the supporting character Waymond Wang (Ke Huy Quan) cutting his hand with a piece of paper to possess the power and speed to fight against the tax officer Deirdre Beaubeirdra (Jamie Lee Curtis). If a cut ignites something, that is smartness to me. Waymond must feel the pain to be stronger. The cut turns on the button in preparing Waymond to transform into a tough fighter.

Daniel Kwan et al. Everything Everywhere All At Once, Lionsgate, 2022.

With this image in mind, the English saying “no pain no gain” rings a bell. On the one hand, the cut for people like me who desire to gain knowledge after break-ups, if not muscles like Waymond, is crucial. In my encounter with my research artefacts, I could not help having teary eyes sometimes when I captured something poignant. The cut is touching, which is heartbreaking in an empowering way when seeing connections between things. There is, nevertheless, uncertainty when the cut doesn’t work.

When I was about to wrap up my thesis, I intensely felt another break-up was pending in my new relationship and did not know how to carry on writing to claim what I learned. That brief moment taught me to be present with pain to bypass it, which makes gains possible. Being present with break-up apps reminds me of the same. Some pain, hopefully temporary and not excessive, can come along in facing break-up apps while reflecting on something difficult in life. Before taking break-up apps as objects for knowledge gains, remember the pain so it is not wasted for nothing.

Pain does not have to be a must, a sacrifice. It should be welcomed more like an entry point for curiosity and knowledge growth if certain objects cause discomfort. On the other hand, facing break-up apps or any other cultural objects related to break-ups does not fetishize pain as a cure. At the time when a person has just broken up, s/he or they may not have the strength for cognitive effort. Thinking may risk ruminating, or simply activating the memories of painful experiences again. Or, an object may register its affect by leading a person to take a course of actions they may later regret.

The aforementioned direction from counter-trauma to trauma is interesting to notice. Break-up apps emphasize the suffering, or discomfort, of a situation in love life. By facing the pain, if not trauma, one may learn and grow. Yet, the way the pain is experienced is also a concern. We do not want the objects to traumatize or trap a person again. Breaking up is technically “relationship dissolution”. A systematic review covering 207 articles from 2002-2020 enlists four definitions of relationship dissolution: (i) a distressing, disruptive and stressful life event, (ii) a decision, (iii) a process, and, most often, (iv) an outcome metric of a good relationship. Some reasonable amount of pain helps one stay with the process of learning to be smarter next time. Break-up apps take on a crucial role among post-break-up events, in mediating the polarities between pain and smartness.

Internet Debate: A Short Overview

A simple Google search with the keyword “breakup apps” shows that many popular digital magazines have interests in the field of interpersonal relationships.

Enlarge

It is important to notice that these articles approach the question of how break-up apps work more openly to help users select an app. One review from PC titled The 5 Best Breakup Apps for Soothing a Broken Heart, published around Valentine’s Day 2023 holds the view that technology aims to be the social glue but at times, it does not mind helping with the issue of separation.

Enlarge

A Cosmopolitan article uses only one line under the title to start.

Enlarge

Break-up apps are self-help tools. For the author Guilla, the benefits of break-up apps are that they can be there 24/7, when human friends can not, and all it takes is a charged battery, internet, and sometimes a small download fee. This argument also applies to the promotion of chatbot therapy apps, ranging from 10,000 to 20,000 options for working on mental health issues, despite the fact that these apps do not advocate for the replacement of therapists.

Allow me a bit of deviation in introducing this debate. Break-up apps seem to be Western inventions indebted to female founders, based on the amount of media coverage. Cosmopolitan is an American monthly fashion and entertainment media company for women with an audience size of 62 billion. It provides content on relationships and love life. The previous beauty director Zoë Foster Blake, an Australian female entrepreneur has an interesting role in the history of break-up apps. In fact, she launched the break-up app called Break-Up Boss in April 2017.

Enlarge

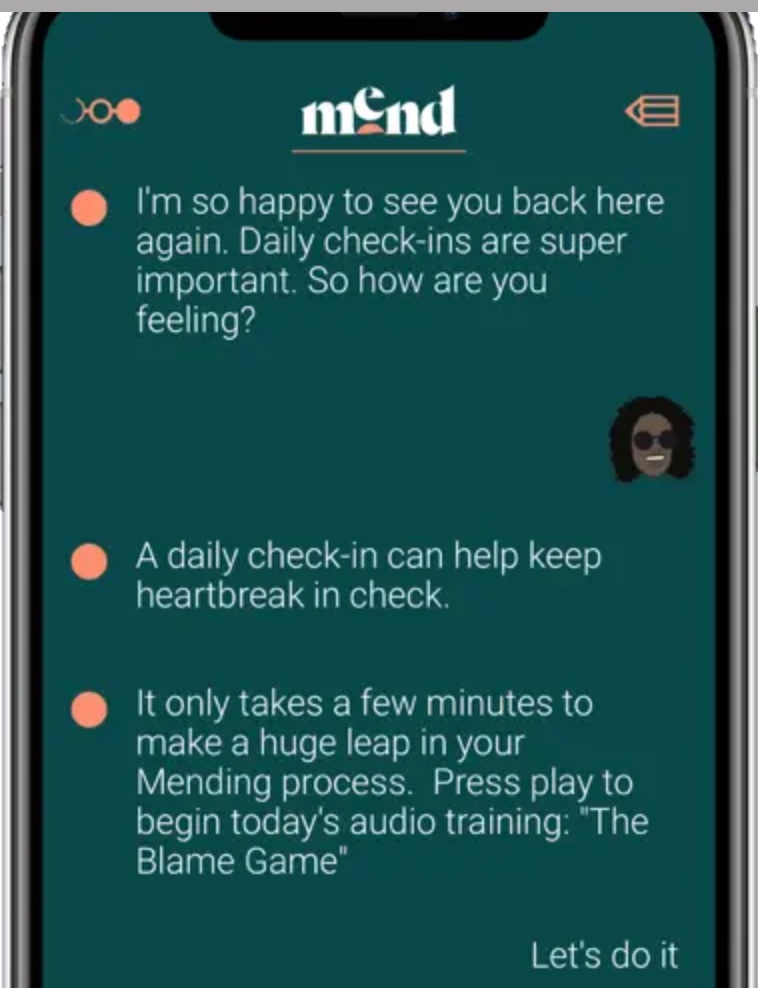

Another app Mend (2013) is also famous for its American female founder Ellen Huerta who quit her analytic lead job at Google to pursue the business of healing a broken heart. Both CEOs are female with high profiles in the digital media and tech industry before their entrepreneurship.

Enlarge

Back when I had no idea about apps like Mend and Break-up Boss, I was reading Helen Fisher – an American anthropologist who is also a renowned self-help book author on love. I thought that would make me smarter to gain knowledge of break-ups. I liked studying and I became almost a student of everything related to love, sex, and relationships after my break-up. I learned of the neuroscientific view of emotional pain due to falling out of love as “real”, comparable to physical pain, and the view of despair (e.g. crying) as an evolutionary coping mechanism. Fischer briefly mentions the Society for the Study of Broken Hearts in India. I was curious about this and it turned out a male sociology professor Ranjay Vardhan who works at the Post Graduate Government College for Girls, Sector 42, Chandigarh started the society, around 1992. It has 150 members. Later, I will reveal why I brought him into the discussion even though he has never done things related to break-up apps. For now, let’s keep in mind this non-Western case.

Enlarge

PC’s article ends with the idea that dating apps may also be useful for those who want casual sex to move on, in line with MUO, which explicitly lists Bumble, and Popular Science, which lists Tinder in the end. The reason? Obviously, sex. According to a general medicine expert, casual sex or rebound sex can make one feel better (in the short term in the author’s words, but I would not open another can of worms to debate about it here). One of the most popular dating brands, Bumble, with 50 million users has stated in the voice of a therapist who is also a founder of a mental health app that rebound sex may be a healthy distraction. No matter how one feels about the effects of dating apps on self-esteem after break-ups, I observe that apps that are not designed for breaking-up are also classified as break-up apps, as long as they may help with moving on after break-ups. MUO has even listed Nike Training, because physical exercise helps the broken-hearted manage stress. Not all of the recommended break-up apps specialize in all the related issues.

Enlarge

In response to those attempts to convince users to buy into break-up apps, some argue that break-up apps are flawed. James Greig, a British political editor at Dazed and commentator for the Guardian explicitly cries out “Sorry, you can’t optimise your way out of heartbreak” in his article title. It was published a few days after PC’s 2023 article, exactly on Valentine’s Day.

Enlarge

Greig used the aforementioned app Mend himself without a break-up to test the water, but turned out disappointed. He refers to a 2020 article by the journalist Diyora Shadijanova, born in Uzbekistan and migrated to the UK, published on Refinery29, a platform owned by Vice, to highlight the bad experience of break-up apps. A user reveals deep suspicion that break-up apps “capitalize on trauma” and “collect your data and exploit vulnerable people ''. This review has no source. Even though Shadijanova criticizes the financial barrier of break-up apps, she is not as critical compared with Greig. In an interview with the CEO of Mend, she mostly approves of break-up apps’ growth. There are of course other questions.

Enlarge

Enlarge

Nonetheless, regardless of whether the aforementioned reviews and articles emphasize the pros or the cons of break-up apps, they make an important lead in public debate in the English-speaking world from the late 2010s to early 2020s.

I intend to join the conversation by adding new considerations and avoiding arguing whether break-up apps are good or bad or worth a try. Passing judgment limits our capacity to learn from an object, a topic, or other people. Although in a different context, Bence Nanay, who transitioned from being a film critic to a university lecturer, expresses that sentiment:

"... I didn't want to be like them (the professional juries). I did not want to become jaded. I did not want to forget how to be truly touched and moved and lifted by a film or by other works of art."5Nanay, Bence. Aesthetics: A Very Short Introduction. iBooks, Oxford, 2019, pp. 190.

If we look at break-up apps as works of art, we may become more interested in experiencing them and observing how they move us by suspending judgments. Furthermore, supposing there are professional critics of break-up apps, larger studies on the effectiveness and reliability of break-up apps are required. More voices of the users themselves are valuable. We must admit that break-ups seem way less important to elected officials compared with urgent problems like climate change, the long haul of the pandemic, or global conflicts. Yet, they touch upon the problem of mental health, which is another global challenge. To tackle that, professional, evidence-based, and scientifically-informed research is needed.

Let’s spread awareness of the ways that app developers may consider to strengthen their apps. For example, when journaling is included in a break-up app, one can learn how journaling about stressful events works in general to advance one’s understanding of break-up apps’ helpfulness. This new perspective does not underestimate everyday experiences of the diary. Nor does it downplay the importance of privacy.

Enlarge

When Blake’s app involves sending a fake text to an ex, what is worth mentioning is the empty chair technique in emotional-focused therapy for specifically studying how break-up apps are tackling self-criticism.

Enlarge

Two psychological research papers published in the late 2000s, Emotional Processing in Experiential Therapy: Why "the Only Way Out is Through." and Dynamic Emotional Processing in Experiential Therapy: Two Steps Forward, One Step Back, specify what one needs to work while going through difficult emotional experiences, including break-ups like separation or divorce. Greig, author of the Dazed article mentioned earlier, disapproves of break-up apps, saying that “these apps assign you tasks”, but according to psychologists, emotional processing is itself a task.

Enlarge

Smartness: A Cultural Difference

The existing debate is limited to the contexts of cultures. The aforementioned opinions are valid, but depend on the societal expectation that break-up apps should help someone move on. “Moving on” in this context means ending a relationship in a “clean” way; most of the time it’s the opposite of what Vardhan would do.

Enlarge

A few Chinese apps share similar views. They primarily rely on people and the apps are meant to make human social support available online, instead of automatizing it. Those helpers have professional licenses and experience: “心理咨询师” / “心理顾问” (psychology counselor), “心理专家” (psychology expert), “情感专家” (emotion expert), “情感导师” (emotion supervisor), and “感情大师” (emotion master) are central to the break-up app and demonstrate the range of support available. One app “依慧心理情感咨询” (abbreviated: Yihun, no longer on Yingyongbao but still on the iPhone App Store) lists two official institutions: the psychology department of Beijing University and psychology studies from the Chinese Academy of Science.

Enlarge

What makes break-up apps “smart” in the Chinese cases is the people behind them - this is what users are looking for, even though there are similar automatic exercises, like for better sleep, meditation, and reading. China also has chatbots like Xiaoice for resolving emotional problems, but I focus on apps that specialize in break-up support, so I will not use a loose categorization.

“App”, full name application, is software for mobile devices. The tech writer John Mortensen argues that “apps on the original iPhone in the year of 2007 turned mobile phones into smartphones''. There is already a connection to the notion of smartness. Further, apps become important when they “support users’ everyday practices” and “insinuate themselves into our daily routines and habits.”6Fernando Van der Vlist et al. "App Ecosystem Analysis". Internal Access, Elective on Appification: The Cultures and Economies of Apps, 2023, pp.1. For example, apps can help with the sticky habit of missing exes at any time – a frequency a person with a full-time job or studies may not afford. The Chinese break-up apps still believe that technology enables experts, whose authority stems from their training and skills, to become available to help each other outsmart break-up pain and emotions. By contrast, most of the break-up apps in the English-speaking world put technology at the center for a fix. It could also be that the break-up apps trending currently are so successful on their own that they eclipse other apps that need not just developers but also other experts.

Another very important difference is the idea of 劝和不劝分, which means persuading others to be together peacefully instead of separated. It is reflected in five apps’ descriptions (亲密关系情感, 异思情感 – no longer on Yingyongbao but on another site, 温度倾诉, 听芝 – no longer on Yingyongbao, 心晴陪伴 ). Take the app 异思情感 (abbreviated: Yisi) with the most downloads (365k) at the time, the word 失恋复合 is used, which means “to repair the relationship when one breaks up.”

Enlarge

The issue resulting from a break-up is not framed as a need for closure, but rather as a need for reconciliation. On Chinese TikTok, I came across a thread of videos about this idea. I take two examples to illustrate the idea of 劝和不劝分 - both advocate respect for long-term relationships and marriage. The reasoning is influenced by Chinese tradition and humor.

Enlarge

Enlarge

In no way am I arguing that Chinese users do not care about ending their relationships clean. Nor do I argue that apps in English do not care about reconciliation. I contacted Marieke Dewitte, a couple therapist and an assistant professor from the University of Maastricht whom I met through the elective course Sexology, during my relationship break and before the break-up. She told me that “so many couples give up and break up so quickly nowadays. Sometimes your relationship is worth fighting for.” It is thought-provoking in retrospect.

Again, the Western break-up apps in the spotlight fight to let go of relationships more, while the Chinese break-up apps fight to keep relationships. Recall the cut in the film when the character fights back. The smartness here is different from one culture to another, demonstrated by what the apps aim to achieve. The pain of break-ups, even though it can be imagined as universal, might still be culturally sensitive for reasons I won’t fully explore here.

Pain: Quotation Counselors and Pharmakon

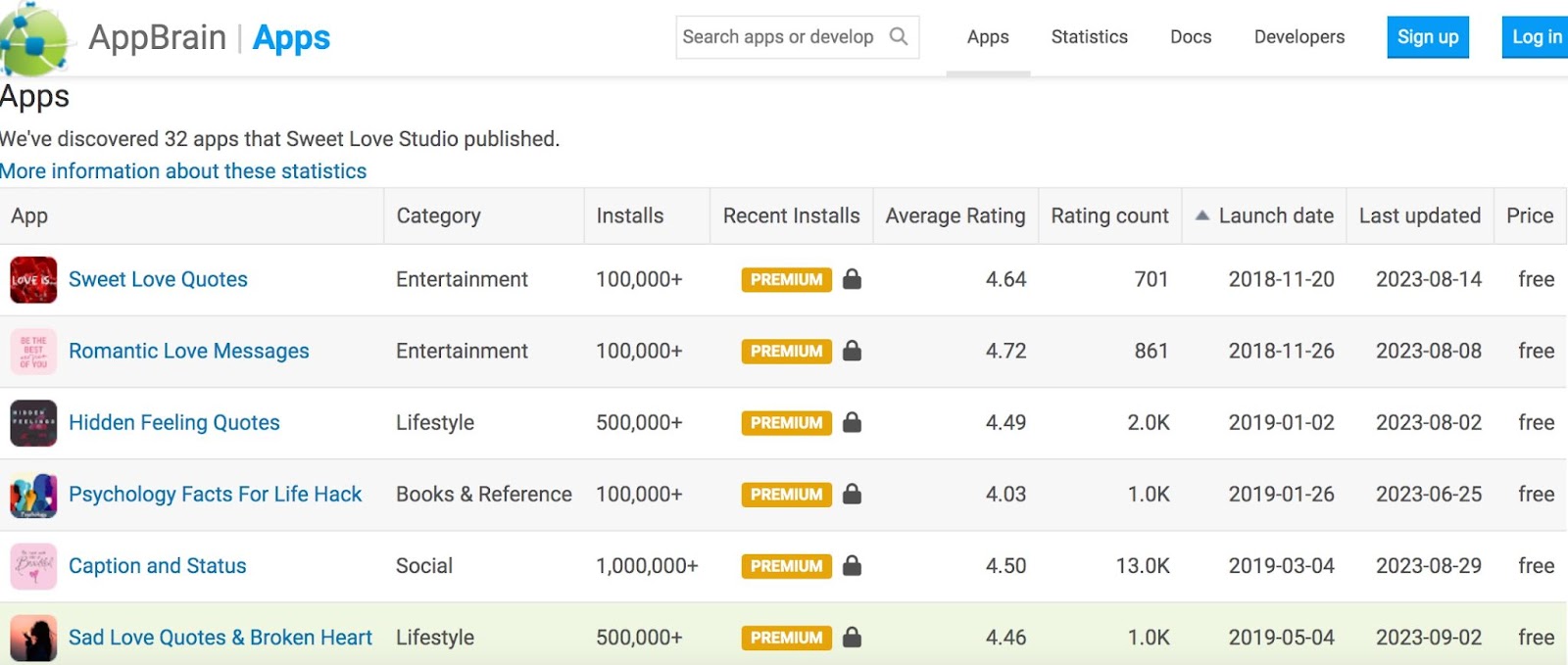

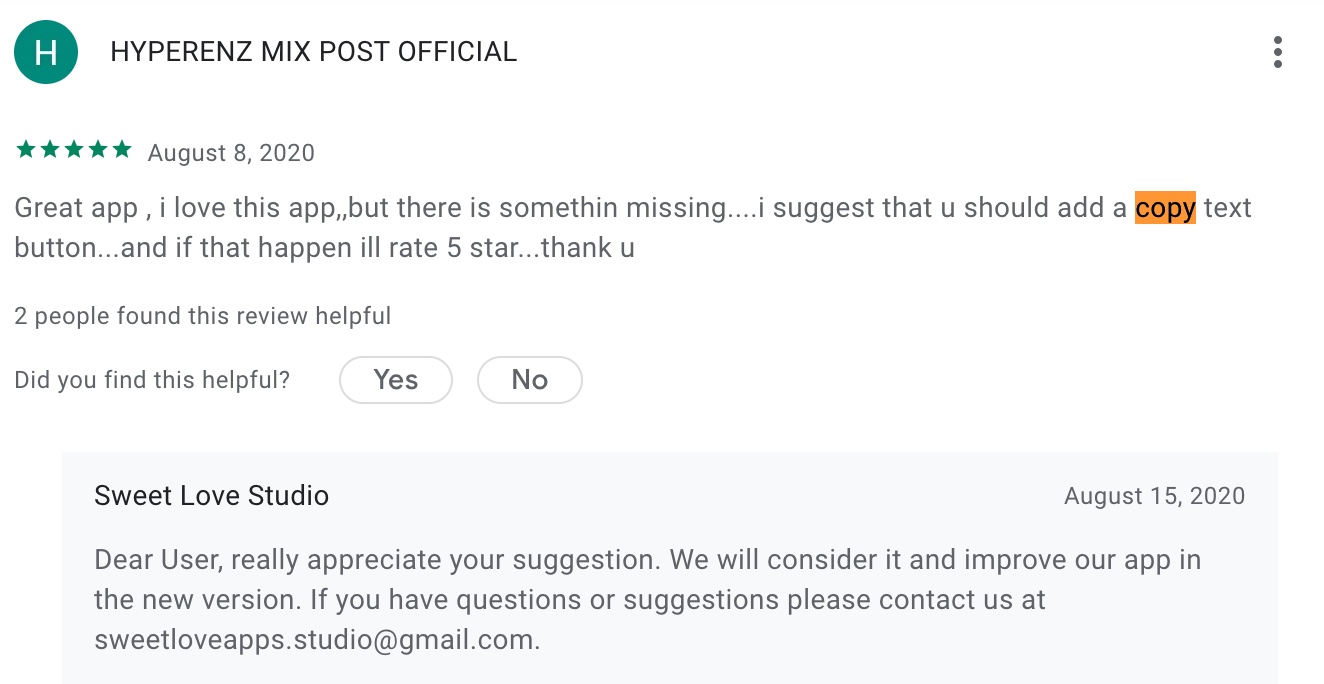

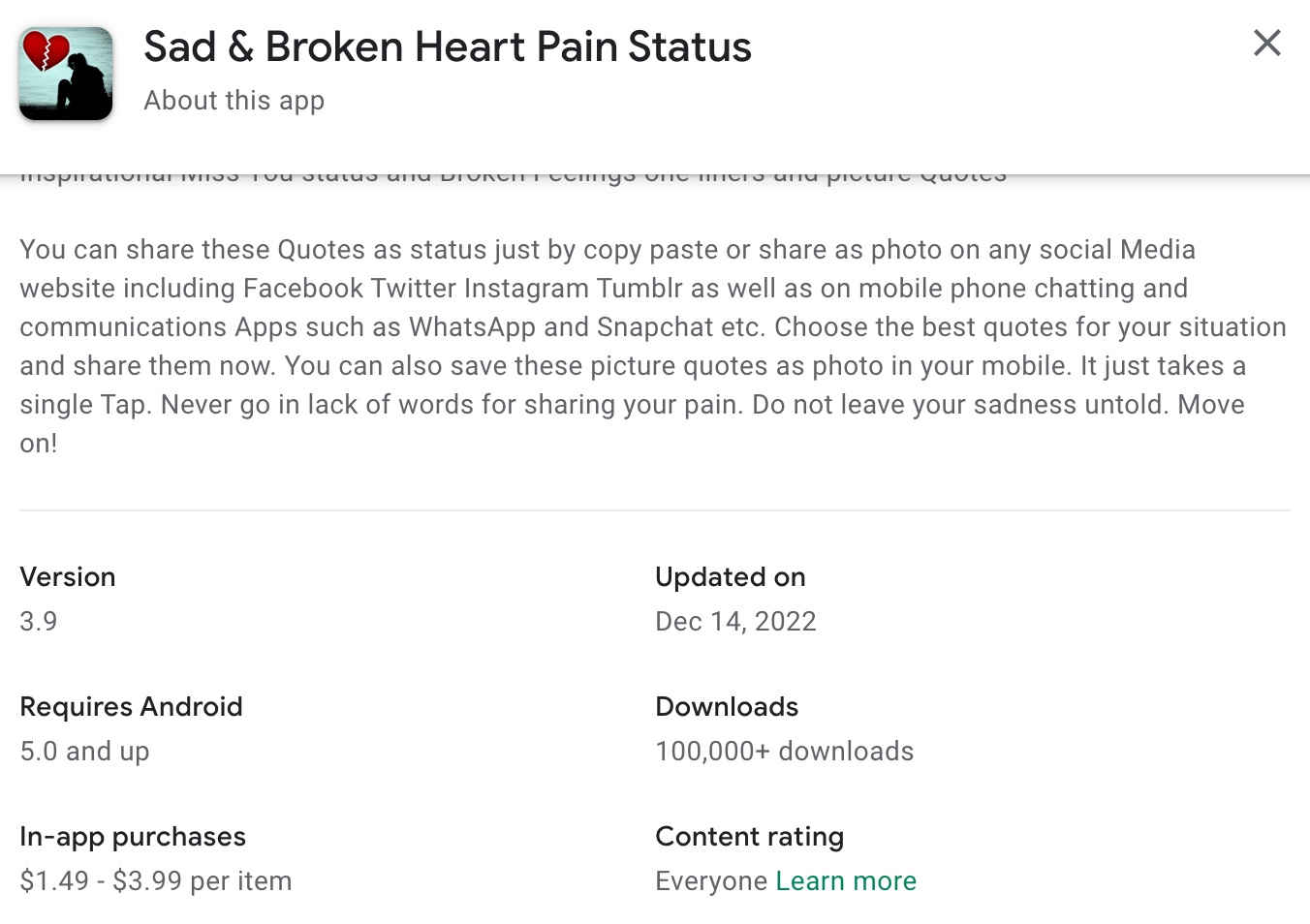

I want to bring up one app from the Google Play store that is free but contains ads, called Sad Love Quotes & Broken Heart by Sweet Love Studio. Given the marketing information from Sensor Tower, Sweet Love Studio has less than $5k monthly revenue. It is a small company that can draw our attention away from the more dominant break-up app players to consider another type of work.

Enlarge

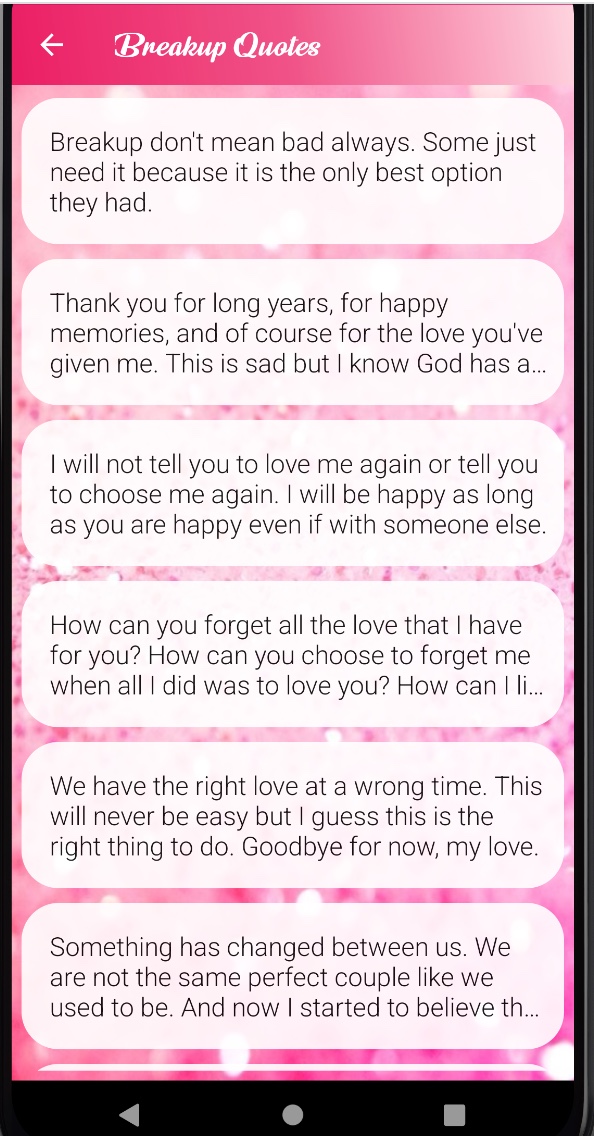

Sad Love Quotes & Broken Heart responds to the need for self-expression, communication, and social support. Their quotes are personal and use first-person pronouns (I-You) to express mixed feelings of regret, sadness, resentment, acceptance, gratefulness etc. The app uses pink to set a warm-hearted atmosphere, which may be why users find the app cute.

Enlarge

As a student with a BA in literary studies, I was embarrassed to think that I don’t recall any quotes from poems or novels to share. Google can quickly fetch quotes with images, at a speed with which I bet my professors could not compete. 500k users may have good reasons to use the app or Google for quote inspiration. The quote type of app is like a literary counselor or media therapist that responds to pain and is there to help. The genre of this type of app links to Bartlett's or a commonplace book, despite that it is digital and has images. Reading relevant quotes that are highly emotionally charged can speak to the users who are going through break-ups.

Enlarge

Enlarge

Enlarge

Enlarge

I hope I may be exempted from the responsibilities of judging the quality of the texts and proving that reading quotes reduces heartbreak pain, though many users agree. I wish to bring up the poison in pharmakon discussed earlier in the context of re-traumatization, now at the end of the discussion. By poison, I mean the harmful, risky, and unruly parts of taking the medicine – a metaphor, of course, referring to any potential therapeutic effects of break-up apps.

Enlarge

Enlarge

Disclosing one’s experiences of breakups publicly by posting app-designed content may increase the chances of gaining support from the social media network, in the forms of likes, comments, chats, calls and maybe more. Such apps praise the immediate act of sharing as not just easy, but also as showing “attitudes” and “letting everyone know your strength”. This copy-paste-post-your-quote method is almost a no-brainer - it might work for those who do not know how to articulate feelings well and those who do not mind being “emotionally naked” in public.

But what should come into our awareness is that app prescriptions for emotional health can lead to new worries. Here, sharing does not let users opt out of the performing culture and disconnect from the internet. The broken-hearted users are nudged to “post” for attention and empathy with the designed buttons under every single quote.

Enlarge

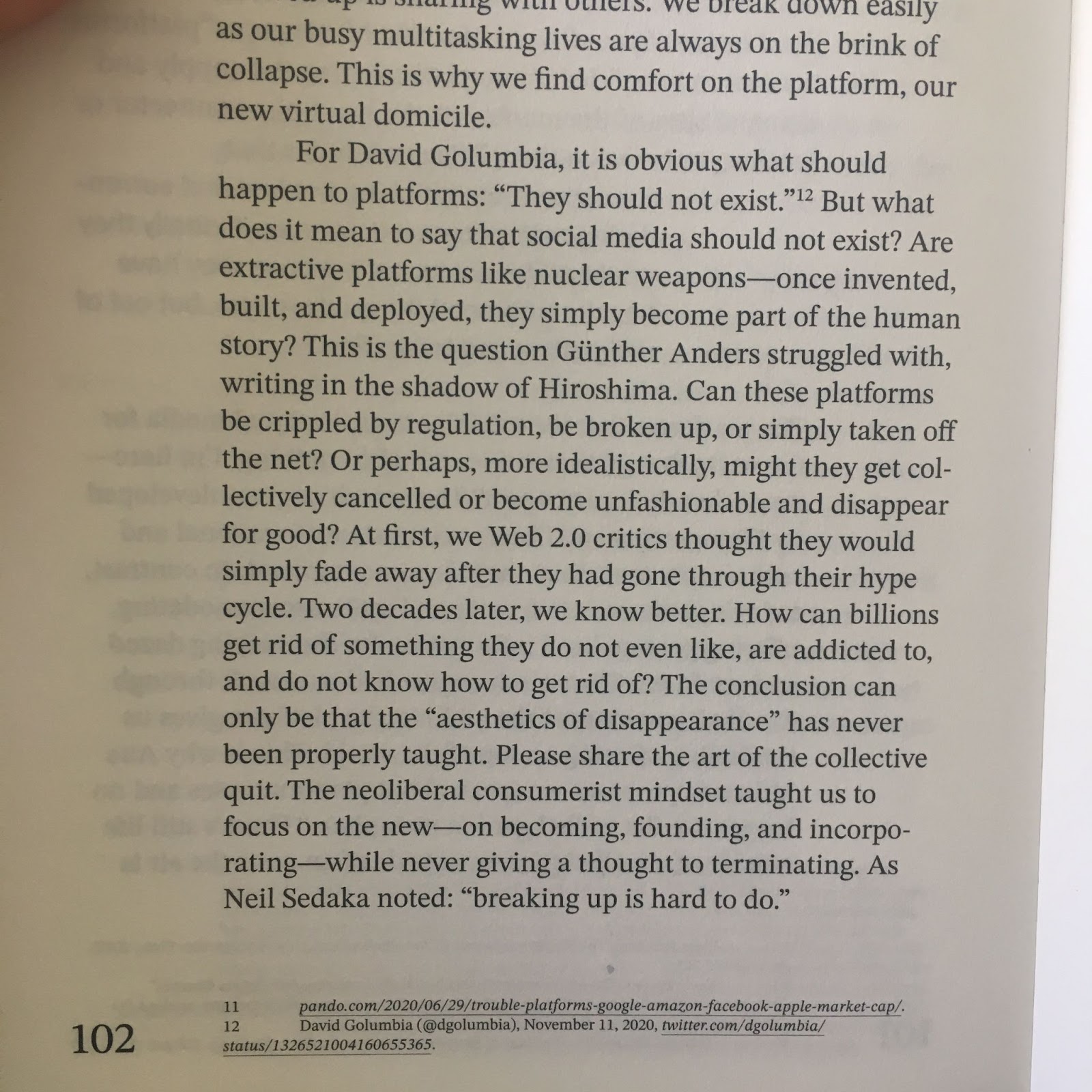

When I cried out of the blue, “Why no break-up apps?!” in my elective course, my professor, Geert Lovink, the founding director of the Institute of Network Cultures, took the issue seriously. I only did more research after that course. When I read more of his work, I found this paragraph:

Enlarge

Enlarge

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tbad22CKlB4&ab_channel=Conkyjoe

I find it interesting that quitting the platform is compared to an act of breaking up. Breaking up can be directed to more situations than just romance. I am not suggesting breaking up with quote apps just because they ask users to share content. We should worry a bit because of Stiegler's reminder of “pharmakon”- “both poison and medicine” in “a new episteme” called “digital studies”.7Geert Lovink and Luke Munn. Stuck on the Platform : Reclaiming the Internet. Edited by Luke Munn, Valiz, 2022, pp. 83. When Lovink analyzes how Zoom took over during the pandemic as a “cure” for social interactions, or “medicine”, or as a solution to the lockdown isolation but led to fatigue, I thought of my objects in the brokenhearted times. I sought literature that can expand our imagination, our creative skills, our learning capacity to identify feelings through reflections, through living with the bodies in the present, our freedom to speak of our feelings without fearing of not doing it well, without depending on the quotation app counselors and its social media brothers…

Takeaway

The theory of smartness and pain related to break-up apps is waiting to be tested in practice and waiting for feedback. Mainly, I want to say that break-up apps are diverse in terms of smartness depending on whom they collaborate with, and in terms of the specific cultural and societal concerns to which the apps respond. For anyone who cares about how smart technology changes human lives, break-up apps teach us to see the pleasure and relaxation users feel through their first-hand experiences. We need more collaboration between psychology, arts, culture, and digital media studies, and more research. Facing the break-up apps is facing the “pharmakon-type” of relation we have with technology and new media.

I was happy to remind myself what I knew and the conclusions I had drawn in the past. I am taking them out of my private world and offering them for takeaway together with whatever exchanges this essay may deliver.

--

Ting Xu studied rMA Cultural Analysis at the University of Amsterdam. Her research interests concern close relationships, emotional well-being, psychology and the arts.

Enlarge