For the original French version of this article, click here:

What relationship can we establish between Chat GPT and a tomato soup thrown on a Van Gogh painting? What invitation does Proust give us, from the analog age, to go beyond the meaningless noises of Twitter? What lessons can we draw, both from present disruptions and from past reading grids, to decode, recode and go beyond the contemporary digital black hole? Let's try a few exercises in improbable concatenations.

If we are not lacking communication, but creation, as Deleuze and Guattari emphasized, and as I have demonstrated in the context of the Web in this article, it is because we are lacking spaces at the margins, free from the imperative of utility and quantifiability. Places that are able to provide a favorable framework for desiring “machinations”, that produce novelty. How can we imagine such a framework within the digital world? How can we relate to algorithmic automation and developments in artificial intelligence, which lead us to rethink the place and role of the human thought as such? In our age of absence of horizon, what strategic bet can we make?

The digital is not a set of tools, but our very culture. The world in which we live, as Marcelo Vitali-Rosati explains – or in which we try, despite everything, to live. The speed of its metamorphoses and the opacity of its functioning makes it, for most of us, bluffing, if not “magical”. Except that its consequences go far beyond the simple performance of magic tricks, in the circus or elsewhere. Digital technology trans-forms us. It frames our actions and standardizes our thinking.

The bewitching and blind magic of today's digital technology can be, with an effort of imagination and the will of a reappropriation, reversed into a new form of techno-magic, no longer illusionist, but participative, imaginative – eminently relational. This is the challenge that arises with the development of artificial intelligences models, such as those of OpenAI.

Let’s try to glimpse how to overcome our situation of “Extinction Internet”, as described by Geert Lovink – as an absence of possibility and imagination, following the capture of the web and its potentialities by Big Tech’s platforms. The issue is one of media, but it cannot be rethought without the support of renewed concepts and without the precise analysis of the algorithmic functioning of our new “tools”.

Codes, Desires and their Creative Arrangements

In the Anti-Oedipus, Deleuze and Guattari refer to code as the set of rules and norms that frame and organize the circulation of flows (the latter consisting, in general, of everything that circulates - including desire). While most societies have coded flows in order to better channel them, capitalism is distinguished, according to them, by its refusal of codes and its extreme flexibility, as Benjamin Nitzer summarizes.

Let’s appropriate this idea of “code”, in a different context, by applying it literally to the coding of our digital media. Thus, decoding will designate the act of decoding what cannot, or should not, be reduced to a computer calculation, while recoding will designate the rewriting of our digital spaces. I do this in a sense similar to Lawrence Lessig's “code is law” - that is, where computer code can protect values, as much as ignore others. As digital technology has become the medium for the majority of the flows D&G are talking about, code must now be thought in both ways: as a standard and as a computer inscription, the two intersecting.

We shall retain in particular the conception of desire developed in the Anti-Œdipus: a desire which, rather than filling gaps, produces arrangements, couplings of the already-existing; rather than remaining in individual fantasy, invests social territories and marks it with differences. From the moment we conceive the unconscious as a factory, rather than as a theatre – as D&G invite us to do – desire becomes creative and thus, revolutionary.1As very well explained by Benjamin Nitzer again, in the first article of his series around the book It becomes capable of decoding and recoding both the flows that traverse our society as well as the digital, which can be seen as the hegemonic medium of these flows.

With these notions in place, let’s consider what constitutes the creative process: a question that feeds many of the debates and criticisms raised by the appearance of Chat-GPT, Dalle-E, and other “generative” models. In these debates, some come to mystify this faculty, while others grossly reduce it, as OpenAI CEO Sam Altman did in this rather revealing tweet:

Figure 1: Tweet by Sam Altman on the 4th of December 2022, in response to this paper

All parrots? Let's explore a few avenues that would allow us not to reduce the entire life of the mind – already well damaged by consumer capitalism, then Meta or TikTok feeds – to a probabilistic calculation.

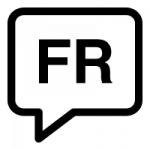

The creative process can be redefined through the concept of the Encyclopedia, which Claudio Paolucci borrows from Umberto Eco (whose thought he inherits and develops at the University of Bologna). Eco defines the Encyclopedia as “the whole of the already said, the library of libraries”, i.e. the whole of cultural uses and norms. Paolucci takes up this idea to describe the creative act (or “enunciation”) as an “addition of subtractions”, made on this whole.2Not without the support of Deleuze and Guattari, of which we find the same logic in the conclusion of the essay What is Philosophy According to Paolucci, in order to create, the painter or writer must not fill a blank surface, “but empty it, cleanse it of the encyclopedic stereotypes that pulsates there”.3See, in English

According to this branch of semiotics – which I believe should communicate much more with the “digital humanities” and “artificial intelligence” programs – the creative act consists of an arrangement between the virtual plane of this “Encyclopedia” and the act which is carried out, individuated and differentiated by the subject. The subject itself emerges from this act, as an actualized, recoded flow of what “pulsates” in the Encyclopedia.

The Encyclopedia, as a whole of the already-said, becomes, according to Paolucci, a “trail of interpretation” that the creative desire travels along: not to repeat it but, on the contrary, to “pull off matter from it”. Creative desire (the two being indivisible, if we stick to the conception of the Anti-Oedipus) has therefore nothing to do with the generativity of texts and images by Chat-GPT and Dall-E, trained on a colossal “Encyclopedic” corpus of 300 billion words for the first,4Although predominantly Anglo-Saxon and 12 million images for the second.

Knowing that these systems essentially consist of probabilistic and predictive calculations, established from the data on which they have been trained, their outputs can be persuasive and even rather relevant, to answer our queries. However, we are far from the “addition of subtractions” of which Paolucci speaks. On the contrary, we are rather in an addition of stereotypes, themselves automatically crawled, and without any real selection, from free access data in the Web Encyclopedia.

A first deduction that can be made from these contrasts is that the role of the contemporary encyclopedist is quite different from that of the Enlightenment encyclopedists. As Paolucci says,5In the book Struturalismo e Interpretazione, p. 186 if Diderot and d'Alembert's objective with their “Encyclopédie” was to square the surface of the Encyclopédie of the time, to arborize and hierarchize its multiple connections, we, in the age of generative AI, must operate syntheses between these elements: weave improbable arrangements, unpredictable connections.

Enlarge

Imagination as bricolage and as overthrow

In other words, in our encyclopedic – that is, creative – becoming, we must imagine, beyond the efficiency of our machines. This requires us to delve into what distinguishes the different faculties of the mind on which Kant worked (understanding, reason, imagination, intuition, sensitivity), as Brice Roy did in his thesis, and to reinterpret them in the face of the “faculties” of AIs.

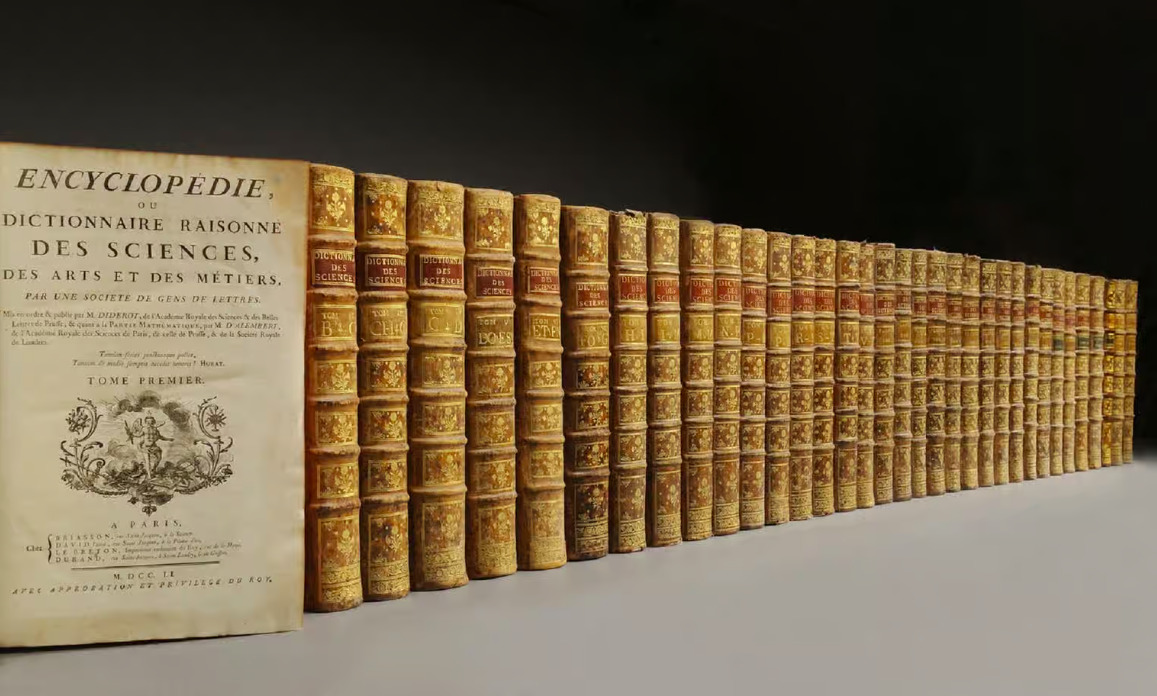

Let us make a brief summary of the faculties that are important to us here. Sensibility is “the faculty that presents to the mind the diversity of the given”, while understanding is “the faculty that provides the rules or categories to follow, without which there can be no intelligence of the given”. Up to this point, we can partly automate these functions, through the collection of data on the one hand, and the prescription of categories on the other, by algorithms.6Even though this partial automation is of a different nature: machinic “vision” in no ways corresponding to human perception (as carefully noted by Jordi Viader) Imagination, on the other hand, is “the faculty that will seize [...] the given variety and synthesize it”. It “will ensure the link of this diversity”, starting by “going through and selecting from the diversity of the given”.7All these quotations are taken from the part “Du caractère pratique de l'imagination”, p. 99 - p. 114 of Brice Roy's thesis, which we have collectively read and annotated within a group of the AAGT-Ars Industrialis, at the initiative of Riwad Salim This is where things get complicated. It seems that deep learning models are capable of imagination, when in response to our queries, they “browse” through the diversity of their data to select some of it, and return a combination, sometimes very bizarre:

Enlarge

However, can we speak of imagination when this selection is devoid of meaning, history and affect? “No emotion, no significance, no meaning helps the machine to select ‘what counts’”, as Giuseppe Longo explains in this excellent interview. Indeed, the way these “neural networks” think, James Bridle tells us, is “essentially inhuman”, because these networks do not have our bodies.

Imagination is a selection – and therefore an exclusion – which consists of an embodied evaluation, Giuseppe Longo tells us.8Giuseppe is a mathematician and director of research in Epistemology at CNRS. See his page This cannot be reduced to an arithmetic calculation, however complex it may be. As for the synthesis operated by imagination, it is fundamentally interpretative, that is to say the fruit of a “critical convergence of affects”, as Stiegler explained in this paper – which also excludes those agents without human bodies and emotions (and which invites us to re-read Spinoza).

With these philosophic-scientific foundations concerning imagination in place, our question can be asked on another, more explicitly political level: how can we protect this incorporated production of imagination from calculations? Or even: how can our imaginations take footing on calculation, rather than being reduced to it? In 2020, Stiegler posited that the improbable, in the era of the hegemony of probability calculations, is diversity.9Text “Noodiversity, Technodiversity”, written in spring 2020 and not published in French, whose translation in English by Dan Ross is vaguely accessible here Three years later, we feel and see more than ever the “systemic elimination of diversity” underway, starting with that of our imaginations.

It is in this perspective of diversification that I would like to quickly praise the figure of the “bricoleur” or “bricoleuse”, as Brice Roy has done, because it goes counter to this integral calculability that standardizes our imagination. As he writes, the inventiveness of the bricoleur or handyman lies in his or her “capacity to emancipate from the prescriptions of understanding, that is to say, on the one hand, to step over them, in defiance of what is said to be possible or permitted, and on the other hand, to divert these same rules in order to use them inappropriately”.

The particularity of the bricolage invention, he explains, “is that it is composed of ‘bric and broc’”, that is to say, of elements marked by a strong heterogeneity and that nothing predestined to be held together. To imagine is to tinker with, and to tinker with is to hold together. Imagination is therefore eminently practical, rather than fanciful: its synthesis “presupposes a holding-together, that is to say, the repeated exercise, over time, of that which prevents the elements from being dispersed”. Rather than knowing whether what is implemented “is consistent with established principles”, what counts is whether it works, Roy tells us – and beyond this functionality, let us add, whether it makes sense.

Inappropriate bricolage,10Rather than rule-prescribed, or randomized, bricolage addition of subtractions ... our AIs are structurally incapable of this, yet it is these very gestures that make up the creative process and imagination – that lead to what, for us humans, makes sense. In addition to these gestures, another no less fundamental source of imagination needs to be mentioned here, if we are to move beyond our incapacity to imagine: that which Nietzsche metaphorically describes as that of the “lion”, in Thus Spoke Zarathustra.

Nothing better illustrates this source of imagination than the recent actions of activists in museums, one of which involved tomato soup and a Van Gogh:

Enlarge

“Creating new values – the lion itself is not yet capable of this – but conquering freedom for new creations – that is what the power of the lion can do”, wrote Nietzsche.11In the “three metamorphoses” part of Thus Spoke Zarathustra (translated from the French) We find this propulsive force today in this type of gesture, which invites us to “rethink the very notion of cultural value”, as Anna Longo explains in this article. It can be seen as “a call to artists and true creators to imagine a new world”.

The reason I mention Nietzsche is that he seems to respond so well to the scandalized commentators of these actions: “Look at the good and the just! Who do they hate most? The one who breaks the table of their values, the destroyer, the criminal – but that one is the creator.” For Nietzsche, creators are “those who write new values on new tables”. And indeed, if there is a “transvaluation” of values to be done, that is to say, a reversal of all values to be carried out – and this is what the multiple ecological, technological and political issues of the present day are calling us to – it cannot be done without this superhuman, seemingly destructive effort. Everything has to be redefined, and this redefinition movement cannot come from our AIs, which rather confine us to the tables of old values.

Digital Reading and Writing

I continue my conceptual bricolage to come more precisely to our digital culture, as such. How can we foresee an eruption of desire in the digital, in its reading, as much as in (the open possibility of) its writing?

To begin to answer this question, I would like to convoke Proust. In a text entitled Sur la lecture, he makes some magnificent digressions on the conditions of a propitious reading. His precepts still apply, for our digital reading:

"As long as reading is for us the initiator whose magic keys open the door to homes we would not have known how to enter, its role in our lives is salutary. On the contrary, it becomes dangerous when, instead of awakening us to the personal life of the spirit, reading tends to replace it, when truth no longer appears to us as an ideal that we can only achieve by the intimate progress of our thought and the effort of our heart, but as a material thing, deposited between the pages of books like a honey all prepared by others and that we only have to take the trouble to reach on the shelves of the libraries and then passively savor in perfect rest of body and mind." Marcel Proust

This long quote, he later summarized as “reading is at the threshold of the spiritual life; it can introduce us to it: it does not constitute it.” The parallel with our times is striking to me, as we are tempted to delegate our minds to Twitter feeds and the truth to Chat-GPT. Although these platforms are far, far away from the “large and marvelous characters of beautiful books” that Proust speaks of. Which is why we absolutely must start desiring again online reading spaces that are alternative to these models, so as to cultivate desire in the digital.

For Proust, of course, reading, imagination and desire are involved in a sort of ménage à trois: “we feel very well that our wisdom begins where the author's ends, and we would like him to give us answers, when all he can do is give us desires.” How can we transcribe the Proustian vision of reading – this “impulse from another mind, but received in the bosom of solitude”, this “imagination [which] is exalted by feeling itself plunged into the bosom of the not-me” – Into digital form? Is this still possible?

Certainly, there is work to be done. We could say a priori that the effort should be more “cultural” and in our practices, than “technological” – although the design of appropriate digital interfaces is crucial. Especially if we define reading with Stiegler as that “place where one takes one's time, where there is an essential delay between grasping and receiving”. This is the antithesis of what Twitter and its infernal feed represents, and it makes one wonder if we can really talk about reading, when we scroll.

Another constitutive practice of reading that is endangered by our current digital configuration, is interpretation. According to this text by Stiegler, published in 1990, we should “eliminate the excesses of exactitude [of our machines] in order to clear a path, to open up a perspective”, by starting to “reintroduce reading as a failure”. I like this somewhat polemical view of reading as failure. What exactly does Stiegler mean by this? Failure, for him, is none other than “the imperative to decide (to interpret)”, decisions-interpretations that are always, to some extent, unfaithful to what is interpreted, heretical: outside the framework of accuracy and what is commonly accepted.

To assert this point of view is to claim one's free right to inaccurate interpretation, as a fundamental human right in our cohabitation with accurately programmed machines. This implies a completely different vision of truth, a plural one, which requires us to go back to Plato in order to better “kill him”.12As Stiegler points out in De la misère symbolique, p. 211: “contrary to what Plato would have us believe, who understands truth as univocity and exactness (orthotes) [...] participation is an interpretation (hermeneai), an activity by which the logos, far from being limited to a meaning, opens up indefinite possibilities of interpretation (masks of the consistency of what is interpreted: the text)” (translated the from French version)

Enlarge

Through interpretation, reading is also writing, if we follow Stiegler. We need this possibility of writing in reading, without which it contributes to a loss of the very feeling of existing. This is why he claims that a true reading of digital memory would be “founded in the open possibility of its writing”, as it was in analogue memory – and it is this open possibility of writing in digital reading that I would like to investigate, as part of my own research. Without going into too much details, such a possibility would have, as its principles:

- To connect with groups that share common interests, groups that would stand apart from the dazzling spotlight of platforms. Here it seems relevant to evoke the book Survivance des Lucioles by Georges Didi-Huberman, who comments on Pasolini's fireflies. These creatures still exist, in “survival” mode, outside the spotlights of the society of the spectacle. Nietzsche had already grasped what was at stake, before the advent of such a society, when he wrote “I no longer wish to speak to the crowd; this is the last time I have spoken to a dead man [...] It is not to the crowd that Zarathustra must speak, but to companions.” Rather than working on a new platform, we should form networks of groups of companions.

- To foster, by its design, discussions of parrhesia, that is, efforts to approach truth, rather than mere reactions, whether flattering or mocking. It would be a question of going beyond the limits of the “freedom of speech” dear to the Americans, whose almost 20 years of Twitter have more than shown us the inadequacy, and of being inspired by the parrhesia that Geert Lovink makes of the internet situation:

- To introduce into its framework something beyond the efficiency of calculations and quantifiability, by starting to favor what Stiegler conceptualized as “consistencies”: that is to say, idealities, projections into the future that exist only between minds, that are the stuff of “dreams” or fiction, but which are nevertheless indispensable to the desire to live together.

It goes without saying that these three principles complement each other in their articulation. What might this “open possibility of writing” look like, in its process and realization, through digital thought-patterns and algorithmic mechanisms? Once again, without going into too much details, here are a few avenues I intend to work on:

- Writing can be seen as a rearrangement, a juxtaposition of pre-constituted materials, rather than invention ex nihilo. This article itself consists of a large and hazardous juxtaposition. From this premise, we can consider new ways of writing via the digital – for example, by rearranging annotations made on other texts, as we have been experimenting with Esther Haberland (with the tools Hypothes.is and Etherpad).13See this report of the Organoesis reading workshop, around the chapter “The destruction of the faculty of dreaming” of the book La Société Automatique. Cuts that we can make through the reading or scanning of texts can be re-weaved in a form of collage-writing. This emerging practice of reading and writing blurs the boundary between the two, and problematizes the very idea of an “author”.14Continuing a movement already well underway by Michel Foucault and others While it is true that the “essence” of the author is challenged by collaborative writing, it can highlight another idea of text, as a common space or “trans-individual reservoir”, in the words of Tiziana Mancinelli co-writing her text with her collective.15In a contribution to the book Unlike Us Reader carried and published in 2012 by the Institute of Network Cultures

- “Computational writing”, a writing that is inspired from programming, constitutes such a juxtaposition and reminds us how writing is weaving: a making of assemblages. It makes links between different code or text fragments, functions that are copy-pasted, modified and brought together in a singular way to serve a particular purpose. This mode of reading and writing is a way of thinking in itself: an “imaginary of code”, in the words of Winnie Soon and Geoff Cox, that is tending to reconfigure human thought patterns altogether. In a similar fashion, the hypertext reconfigures our ways of thinking through a reading and writing that allows itself to become multi-directional, rather than linear and searching for one specific end goal. In its navigation of the Web ocean, hypertextual thinking allows itself some drifts.

- Finally, since we are talking about the digital medium, writing can and must take place within the very algorithms that pattern content. That is to say, in what makes some visible and others invisible, what allows or constrains their circulation. It is important to understand that the former “guardians of the debate” (journalists, publishers, academics, etc.) are gradually losing their monopoly on filtering the debate, with the rise of the “social web”, but that nevertheless, “far from disappearing, selectivity has been reconfigured through algorithmic sorting”, as explained in this article based on the work of Dominique Cardon.

Let's leave these avenues at that for now. This attempt can be summarized as a “provocatype”,16As Geert Lovink talks about it in Extinction Internet, to envision an overcoming of the usual prototypes, whose innovation is only incremental going against the grain of dominant conceptions of the digital and automation, of reading and writing, of community and discussion. The more media-related challenge is to overcome our dependency on traditional media, as decried by Serge Halimi and Pierre Rimbert in Le Monde Diplomatique (but for which they have neglected the media counter-power that the digital can be, even in the example they take of the referendum on the European Constitutional Treaty in 2005, in France, where they totally denied the fundamental role of the emerging web forums in the mobilization for the “no” vote).

Technomagical Regime and Narrative

We need to link all these tracks and principles to a narrative, a broader imaginary. Something propulsive for such initiatives, capable of reconfiguring the digital and its practice. What narrative can they fit into?

In Out of the Wreckage, George Monbiot reminded us of the human and strategic need to forge stories that enable us to navigate the world and interpret its diverse and contradictory information. Narratives that can resonate with our actuality, as well as our desires and projections. If it is true that the neoliberal narrative has lost its compass and its power of persuasion, as we have shown in this blog post and this one, we must replace it with another narrative, because “the only thing that can replace a story is a story”, as Monbiot says (and as Geert Lovink echoes, to pose the challenge in terms of alternatives to platforms).

Here is the beginning of the story I propose: we live in a techno-magical regime.

The word “magic” is often used when talking about what “artificial intelligence” is capable of. In fact, this dates back to the 1970s. More recently, Tristan Harris (ex-Google) wrote an article about how his work as a Design Ethicist at Google (i.e. in relation to the so-called “ethics of persuasion” of Google's programs) was a magician's job.

“I am an expert on how technology hijacks our psychological vulnerabilities. I learned to think this way when I was a magician,” he says:

Enlarge

“Magicians start by looking for blind spots, edges, vulnerabilities and limits of people’s perception, so they can influence what people do without them even realizing it […] And this is exactly what product designers do to your mind. They play your psychological vulnerabilities (consciously and unconsciously) against you in the race to grab your attention.” The rest of his article goes into more detail about these digital magic tricks made in California.

On the other side, that of the “users” (rather the used, if we are to believe Harris), a form of “magical thinking” appears, the one that Serge Abiteboul and Jean Cattan denounce as consisting of “accepting everything without thinking, or refusing everything outright”. According to them, we could however get out of this Manichean logic, with “a little knowledge of the world of algorithms and software”. This would enable us to understand “that there is no magic in them, that they were designed by humans, with their limits”.

Nothing is self-evident in programs. How much do we want to see what goes on, behind the scenes of these magic tricks? Do we want to grasp these techniques, or would we prefer it to remain a form of magic for us? This is what Megan Graber asked back in 2012 in the article “Americans Love Google! Americans hate google!”.

The question is still being asked, and even more so with the growing importance of the cloud, which can be understood as a magical way of not having to think about servers and their maintenance, as well as all the power relations are at stake there. When we upload content to Google Drive or videos to YouTube, for example, we are delegating our memories (which they can erase at any time, and whose data they manipulate against us) to the mega-company Alphabet, in exchange for simple interfaces and systems that hardly ever bug. We were talking about this cloud thinking habit at an INC event, which I reported on here.

Today, it is Chat-GPT that is the center of all attention. But if we dig behind his magic tricks, we see nothing more and nothing less than a very sophisticated system of “bullshitting”, of deception. Chat-GPT doesn't care about the truth: He is in bullshit, as are most of our politicians. Of course, we could give other examples, such as dating sites that present the cold calculations of their algorithms as having a magical dimension, allowing one to meet the unexpected, “destiny”.17See Mektoube The magical, elusive complexity of love here meets that of algorithms, as Vitali Rosati has put it.18In his book On Editorialization, accessible here

This is why we are in a techno-magical regime, as Vincenzo Susca wrote in a book in Italian entitled Tecnomagia. According to this researcher, “tecnomagia” consists of a “voluntary and globally unconscious alienation of the social body” by platforms such as Netflix and TikTok, an “aesthetics of malaise” that makes us enter collectively, and in an accelerated way since COVID-19, into a kind of “dance of death”. Using the notion of totemism, Susca clarifies the links that have always existed between religion, technology and magic.

However, it seems to me that the phenomenon Susca talks about in relation to the digital – and indeed all the phenomena I've just mentioned – is more a matter of what we might call techno-illusionism. I say this because I believe that the idea of magic could still refer to an open space of possibilities, something improbable and incalculable. Even though techno-illusion presents itself as techno-magic, we can see that it is rather a form of bewitchment and largely unconscious control, an attempt to determine and monopolize our attention.

I return to this need for a propulsive narrative. If “Internet extinction marks the end of an era of collective imagination” and alternative techno-social arrangements, as Geert Lovink states, then techno-magic could mean “an energy freed up to create new beginnings”. This “writing machine”, as Franco Berardi calls it, which was put into motion during COVID-19 and which aims to “rewrite the poetic and computational software of social interaction”.

True techno-magic can be this unprecedented creative breath emerging from our clogged circumstances. Even if extinction has already been decided – the extinction of the biosphere as well as that of the Internet – we can still perform our most beautiful dances, and these do not have to be macabre, unlike what Susca thinks. This is a generational point of view: don't stick to the macabre. There is life allowed by and in death: it's a question of relationship, of how we inhabit it. Let's not be too absolutist about the future. This is a story that has yet to be written by the new generations.

We need to generate dreams within the nightmare of the third unconscious described by Berardi; a new horizon of desire, within the very probability of extinction. We can do this through a new movement of the imagination, itself techno-assisted (there is no imagination without technics of imagination). This movement, imaginative and desiring, can be thought as a dance. A movement which comes from the body, and which aims at the body. Beyond Freud's desire as theatrical representation, and Deleuze and Guattari's desire as factory production, desire as a dance movement conveys something that is both insolent and healing: a desire closer to what makes us feel alive, and that can break stuff. Moreover, if erotic perception is more and more replaced by a computerized, informational perception,19As Berardi suggests in And: Phenomenology of the End (2015) dance invites us to this conjunction between the bodies of which we are tending to forget the inaccuracy, the ambiguity, the impertinence.

This is a story’s beginning for a techno-magical way out of the techno-illusionism. A lucid and desirable political and affective narrative for the 2020s, giving us a glimpse of a techno-emancipatory way out of techno-feudalism.

Enlarge

More concretely, techno-magic could be constituted around technologies capable of forgetting – as forgetting is essential to be able to imagine. This would require working on alternative databases which, in addition to not retaining everything forever, leave room open for what cannot be encoded in them. What cannot be encoded? Relationships – love, rivalry, desire – that cannot be substantiated as data. By definition, a relationship cannot be reduced to a substance: it is an “incalculable”, a form of well-kept, though shared, secret.

So we need to think in Spinozist terms, as Yves Citton and Frédéric Lordon invite us to do – where the identities of individuals and objects themselves become relations, or more accurately “relations of relations”. Here is a form of magic, if we take up their words: a “relational production of relations and identities”. A complexity and a mystery that escapes us, that will forever escape the automatons. If we do not affirm this magic, we are in fact allowing ourselves to be deluded by the latest technologies from Sillicon Valley, which make us believe that everything can be reduced to their calculations. As powerful (and above all energy-consuming) as they are, these calculations are only arithmetic.

The techno-magical narrative, which has yet to be written, can also be that of an arrangement of affects through technology and a recoding of what makes us share common desires. If political life is indeed, as Citton and Lordon say, a set of “phenomena of composition and propagation of affects”, then we must recompose it from the computational context, which is today the main manipulator of our affects.

Our digital context favors impotence, in reason (with the arrival of Chat-GPT) as much as in meaningful action (by its absorption in oceans of insignificance, as Twitter can favor). It also encourages the atomization of individuals, reducing them to profiles. A techno-magic would therefore appear in spaces where a power of the multitude is reconstituted, where our affects and links are recomposed. This space, at the edges, would (re)open the floodgates of a circulation of this power and would thus be able to serve the “alter-shock doctrine” that Stiegler called for during his last months.20See for exemple this seminar

Edges and their Supports

From a mathematical and semiotic point of view, to speak about “digital space” is out of place, if we take up the works of Giuseppe Longo and Jean Lassègue. According to the first one, “the digital was born not to have to do with the space”, because the digital coding consists essentially in an arithmetic sequence born from the crisis of the Euclidian geometry. “A way to break space is the linear coding of the world”, he answered to a question I had asked him, last March 31. According to him, “the networks of computers constitute another ‘space’ than that of the living and its action, a space with arbitrary topologies and distances.”21For more details, read the book Le cauchemar de Prométhée, published by PUF this month

According to the second, there is no continuity between “the space lived by the speaking bodies that we are [and] the lines of codes [...] which are the result of a writing detached from any relation to space”. His diagnosis is ignored; however, it is heavy of consequences: “it is the differential between the lived space and the non-space of the lines of computer writing where the problem of the collective construction of sense is situated today”. This is how this researcher links the “crisis of the democratic decision” to a “generalized delegation of reading and writing to computers”.

Notwithstanding these considerations that seem fundamental to me, I would anyways like, on a more strategic and metaphorical level, to speak about digital space, with Marcelo Vitali-Rosati – even if this space would constitute another space, with its own rules. As he explains it, the space can also be thought as the result of relations between subjects and objects: not something stable and independent, but dynamic. These relations being written, in the digital medium (codes creating dispositions between different “objects”), we can investigate these codes as particular interpretations of the world and ways of inhabiting it.

In “digital space”, every object is encoded – even images, even videos. Even our actions on the Web are written: a click is registered as data in several databases. “Outside” and “inside” do not work in the same way, because the same object – a collaborative document, for example – can be in several places at once, and the same goes for “center” and “periphery” (the same collaborative document can be at the center of a discussion forum and at the margins of an email exchange). Likewise, the “social text” that Bob Stein talks about emphasize how conversations at the margins of a text can, in certain digital arrangements, become something which is central to it.

The delimitation is inclusive rather than exclusive, therefore, in the digital space, as Vitali-Rosati explains, with subjects and objects capable of occupying several positions at the same time. There are boundaries on the Web, without which it could not function – but they are porous. The web is striated and smoothed at the same time. Space is thus multiple, and it can thus produce multiple meanings, in fractals. The disorientation induced by this plurality, we find it genially expressed in the movie Everything, everywhere, all at once, where cinema becomes the ideal messenger of this collective feeling of the “digital era”:

By politicizing the digital space in this way, Vitali-Rosati politicizes this dimension that I want to develop of positioning – positioning that would be specific to this space that is not really one. The question of center and edges is a question of hierarchy, in physical space: according to V-R’s example, the fact that the cathedral is in the middle of the city means something, at least historically, about the organization of political power. Where do we stand in relation to the center of power? One position that seems strategic to me is that of the edges, but as we have seen, in the digital world, that same edge of a space can be the center of another.

It is here that we must once again call upon the desiring machines of Deleuze and Guattari. While reading them, I find this quotation that applies very well to what I want to elaborate: “It is possible that the desiring machines are born in the artificial margins of a society, although they develop quite differently and do not resemble the forms of their birth.” An edge does not have vocation to remain at the edge. If “in the center there is the machine of the desire”, the stake would be, always by resuming their words, to develop “experiences and machinations that overflow it of all parts”. A bit like the “roundabouts” of the French yellow vests, which have de-bordered from the periphery, the center of the machine of the Macronist power. To make strategic sense, the edge must reach the center. We can think of this as a movement of reconquest, operated by desire.

These considerations can seem abstract, excessively conceptual; however, they refer to a way of making politics quite concrete, daily, immediate. Edges, digital or not, can be this space where we tinker by recovering materials produced by the system of power in place. They can be this approach, where rather than rejecting entirely the efficiency of calculations and algorithms, we use them to favor a process of diversification. Or it can be a metaphor for the challenge of getting out of capitalism through digital capitalism, paradoxical as it may seem, by introducing techno-magic at the edges of its techno-illusions. This is how Wikipedia came to be, and it does not have to remain the exception of the digital black hole.

Speaking of black holes, we must remember the work of Stephen Hawking, who showed how black holes do not only absorb energy and matter. They also emit radiation, at their edges. Black holes are full of paradoxes:

Enlarge

Edges are in the space of bodies that Longo and Lassègue talk about, just as in the space of relationships that Vitali-Rosati talks about. They encourage us to stand aside, as a moral principle,22see this round table with complicated dialogues, on the question of desertion and bifurcation just as they invite us to adopt, as a collective strategy, a politics of decoding and recoding the different spaces that transform us. Edges hold us in a movement of oscillation, of fluctuation.

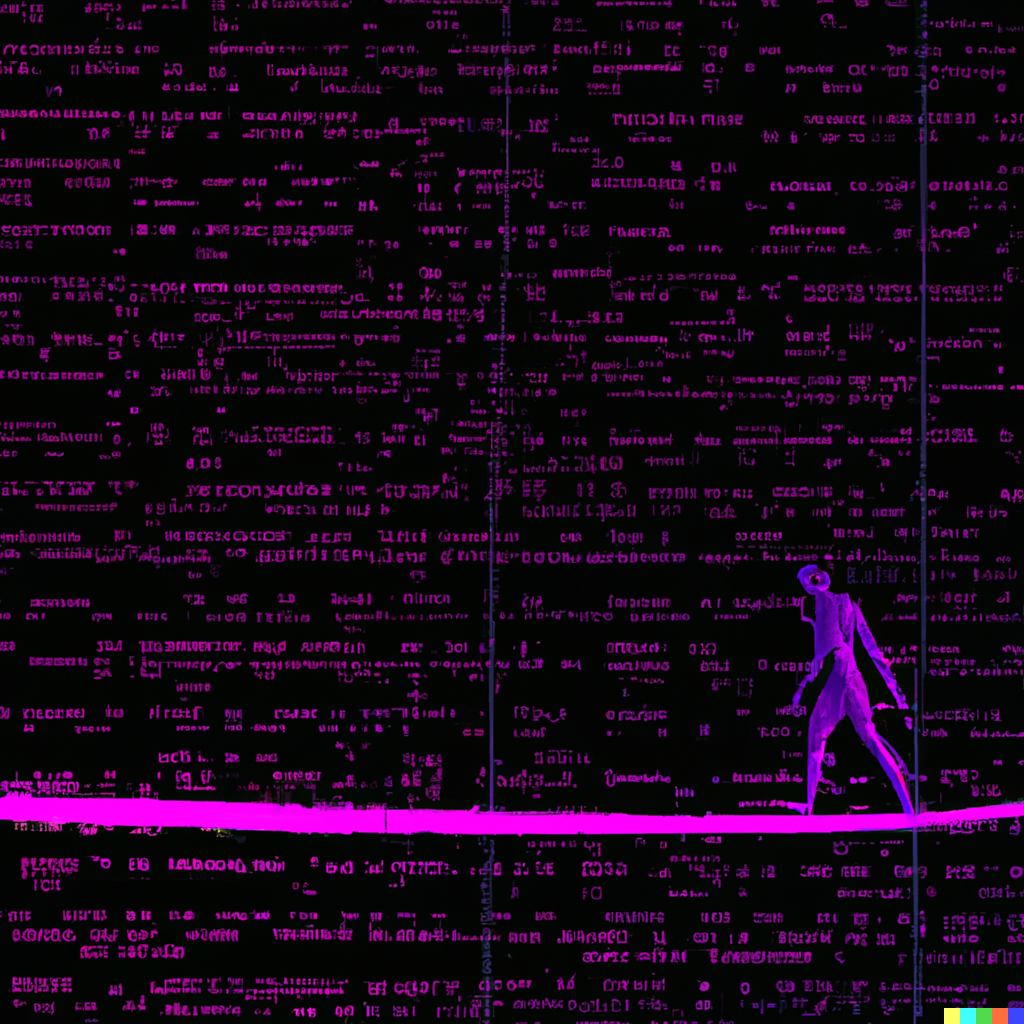

When we are on the edges, we stand between desertion and compromise - always in an unstable, fragile way. We try to instrument ourselves, without being instrumentalized. We are real tightrope walkers, in a form of prowess, at the edge of two precipices, of two voids.23Or rather, as Somhack Limphakdy suggests to me, “on the one hand, yes, we are faced with the void, but on the other hand it is nothingness. If in both cases we are indeed taken by vertigo, the first opens up to the very indeterminacy of the living, while the second would close in on us, destroying the ‘possible’ itself [...] this is the pitfall we must avoid and therefore face, and take a firm stand on” (by email, on the 17/04/23, in response to these lines) We are a bit like this strange figure, which was spat out to me by the artificial image generator Dall-E, to whom I gave the instruction “a tightrope walker over a sea of digits in a cyberpunk style”:

Enlarge

Actually, for this techno-funambulist to hold, we will need some institutional supports. The edges must be fed “through and through” by the system, wrote Stiegler. We will have to conquer their material conditions of possibility and claim them through the streets – like the current movement does in France, against the pension reform and the bypassing of the parliament, syndicates and citizens (more and more, against what Macron represents).

How can we generalize the work of creative imagination that I mentioned at the beginning, without a financial security capable of freeing up our time? If the work of employment is for many of us alienating, a work freed from employment would be to impose on the debate of the “reform” of pensions, a debate that is far from over. Retirement can also be seen as a prefiguration of this liberated work, much more than a right to laziness (although laziness can be very creative).

New generations have the right to their own form of retirement, too: the right to fail, for example. Our economic context does not favor our risk-taking, lacking more and more forms of economic security capable of absorbing our falls. Yet it is this same generation that is asked to “save the planet”, to get humanity out of the systemic mess in which it has – or some have, as the case may be – pushed itself.

There are no creative and transitional edges, as Stiegler has called them, or liberated and overflowing desiring productions, as I have tried to imagine in this longform, if we don't have an economic safety net – providing us with the material stability and insurance necessary for imaginative, desiring freedom. This is why we need to rethink the social security system, as this tribune in Le Monde, written and signed by several members of my Association, invites us to do – which starts by redefining beyond GDP the notions of “wealth” and “value”.

Here, I tried to draw a sketch for overcoming our technological and political situation, which has no horizon, other than extinction – starting with diversity in general. A tightrope walker's path: that of decoding and recoding, without guarantee, of our techno-social regime. A way however capable of arousing in me, a desire, which I hope to make shared.

—

Victor Chaix is currently a Master student in Digital Humanities, at the University of Bologna. Interested in the philosophy and the semiotics of the circulation of online information and meaning, he has worked both for an online newspaper and within projects launched by Bernard Stiegler, while he was in Paris. He currently prepares his Master’s thesis at the INC, theorizing and experimenting new possibilities for the “social text” – a heightened potential for texts in their digital configurations opened up by the like of web annotation, collaborative writing and metadata interventions. He is also a founding member and vice-president of the Association des Amis de la Génération Thunberg (AAGT), for which he is in charge of the blog.

A special thanks goes to Esther Haberland, Giuseppe Longo, Somhack Limphakdy and Jordi Viader for their inputs, and to Geert Lovink, Chloë Arkenbout and Kate Babin for their re-reading of this text at the INC. Many of the references in the “techno-magical regime and narrative” part have been shared to me by Igor Galligo, and some crucial references in “digital reading and writing” are taken from seminars co-organized by Anne Alombert. The translation into English was facilitated by the translator DeepL.

—

References list

Serge Abiteboul and Jean Cattan, Nous sommes les réseaux sociaux, Paris: éditions Odile Jacob, 2022.

Franco Bifo Berardi, The Third Unconscious, London: Verso Books, 2021.

Yves Citton and Frédéric Lordon, Spinoza et les sciences sociales. De la puissance de la multitude à l’économie des affects, Paris: éditions Amsterdam éditions, 2008.

Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Qu’est-ce que la philosophie ?, Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 1991.

Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, L’Anti-Oedipes, Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 1972.

Jean Lassègue, ‘Sur la construction collective des signes : l’Ancien Régime et la révolution’ in Anne Alombert, Victor Chaix, Maël Montévil and Vincent Puig (eds) Prendre Soin de l’Informatique et des Générations. Hommage à Bernard Stiegler, Limoges: FYP éditions, 2021.

Lawrence Lessig, Code And Other Laws Of Cyberspace, New York: Basic Books, 1999.

Geert Lovink, Extinction Internet, Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2022. https://networkcultures.org/blog/publication/extinction-internet/

Geert Lovink, Stuck on the Platform. Reclaiming the Internet, Amsterdam: Valiz, 2022.

Georges Monbiot, Out of the Wreckage. A New Politics for an Age of Crisis, London: Verso Books, 2017.

Friedrich Nietzche, Ainsi Parlait Zarathoustra, Paris: Librairie générale française, 1972.

Claudio Paolucci, Strutturalismo e Interpretazione, Milan: Studi Bompiani, 2010.

Brice Roy, Penser le jeu à l’ère du numérique : une approche à la croisée de la phénoménologie et de la théorie des supports, Compiègne: Université de Technologie de Compiègne, 2019. https://theses.hal.science/tel-03119573/document

Bernard Stiegler, Aimer, s’aimer, nous aimer, Paris: Éditions Galilées, 2003.

Vincenzo Susca, Tecnomagia. Estasi, Totem e Incantesimi Nella Cultura Digitale, Milan: Mimesis Edizioni, 2022.

Marcelo Vitali-Rosati, On Editorialization. Structuring Space and Authority in the Digital Age, Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2018. https://networkcultures.org/blog/publication/tod-26-on-editorialization-structuring-space-and-authority-in-the-digital-age/