‘Non art is more art than art art’, Allan Kaprow claimed in 1972. He concluded: ‘Artists of the world, drop out! You have nothing to lose but your professions.’ Are we ready to move on? From the 6th until the 9th of June 2024, an international group of art workers gathered at Floating Berlin to explore this question during the Konteksty Postartistic Congress.

Konteksty is a unique phenomenon. It was founded in 2011 as a yearly performance festival in the southern Polish mountain town of Sokołowsko. Then, in 2020, it was transformed into the world’s first and only postartistic congress. Every year since, Konteksty brings together postartistic practitioners ‘to explore what can be done with art today instead of distinguishing between what art is and is not’.

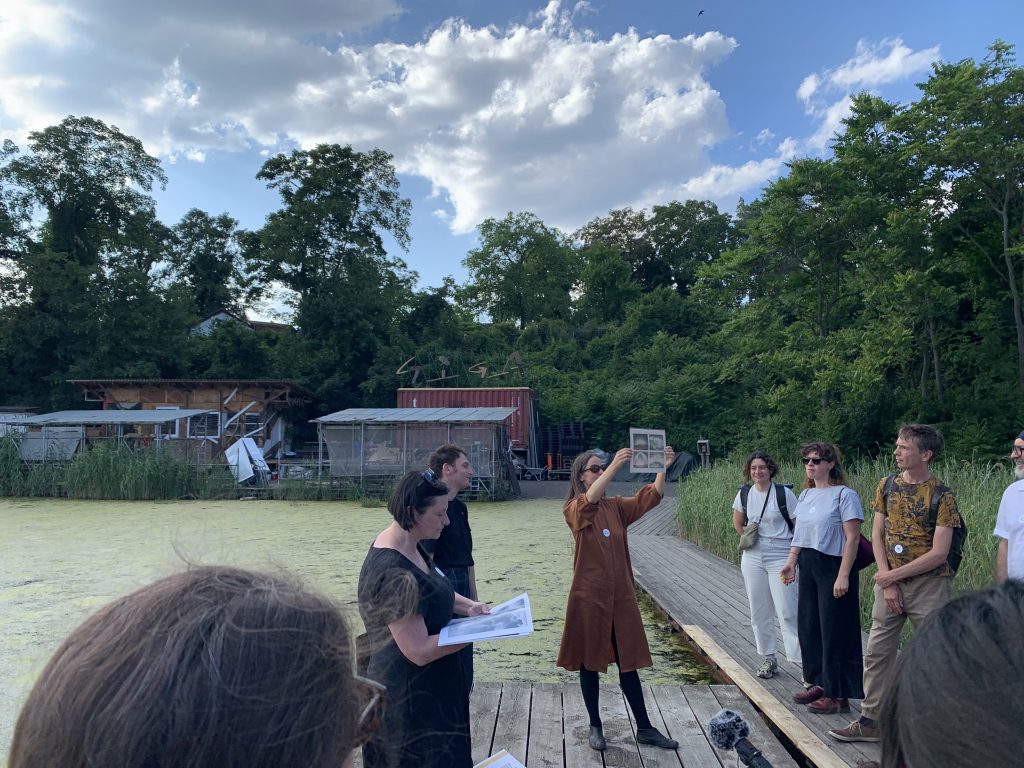

This year’s edition, the first international adventure of Konteksty, centered on postart and ecology. It took place in Floating, the old rainwater basin of the Tempelhof airport, and one of the most idyllic places I know. The shallow, swampy lake is located in the middle of Berlin, but entirely secluded thanks to the surrounding trees. The ‘building’ itself is a web of wooden docks and structures throughout the basin. But it was not just a nice place to be. As the program of visual lectures, farm art screenings, post-digital eco LARPs, and nature offerings progressed, I realized Floating was a fitting laboratory for three days of postartistic experiments.

Some of the pavilions of Floating (f.k.a. Floating University) in the rainwater basin of Tempelhof.

What Is Postart?

The idea of the postartistic era was coined by the Polish art critic Jerzy Ludwiński in 1972. He wrote: ‘It is highly likely that today we are no longer dealing with art. We simply overlooked the moment when it transformed into something entirely different, something that already escapes our capacity to name it. Beyond any doubt, what we are dealing with today has a greater potential.’ However, it wasn’t until 2015 that a group of Polish practitioners started seriously exploring this potential. During this year, the radical right-wing PiS party came to power in Poland and started implementing a series of infamous policies: undermining the independence of judges, announcing ‘LGBT-free zones’, and making political appointments in state-funded cultural institutions and media. The postartistic disposition offered a way to simultaneously retreat and politicize the practice of the contemporary art scene.

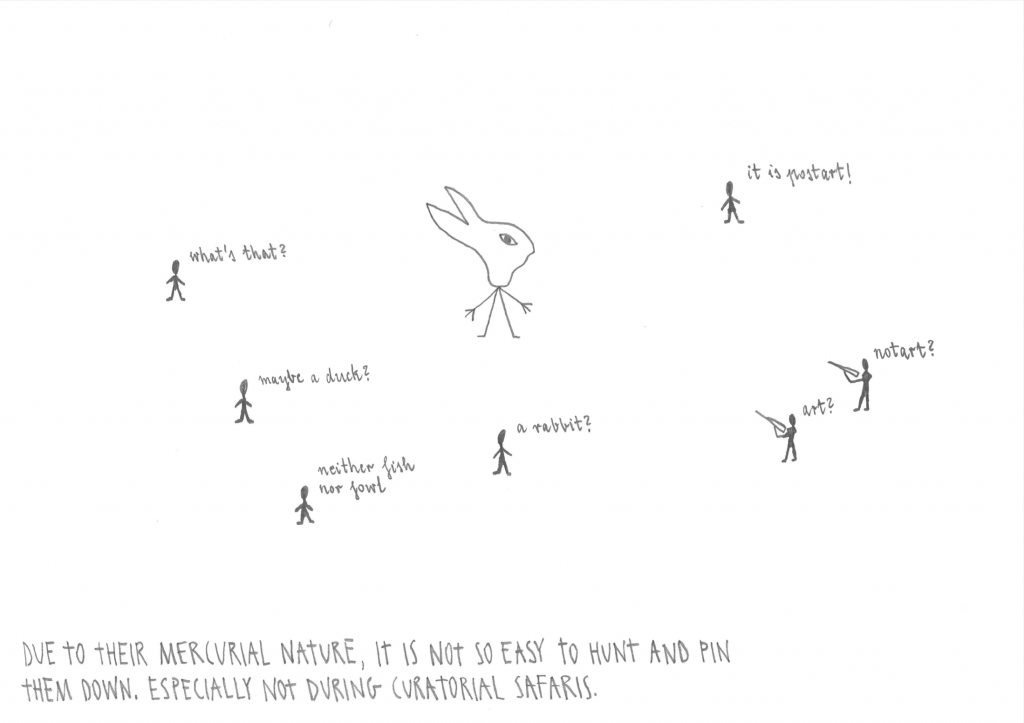

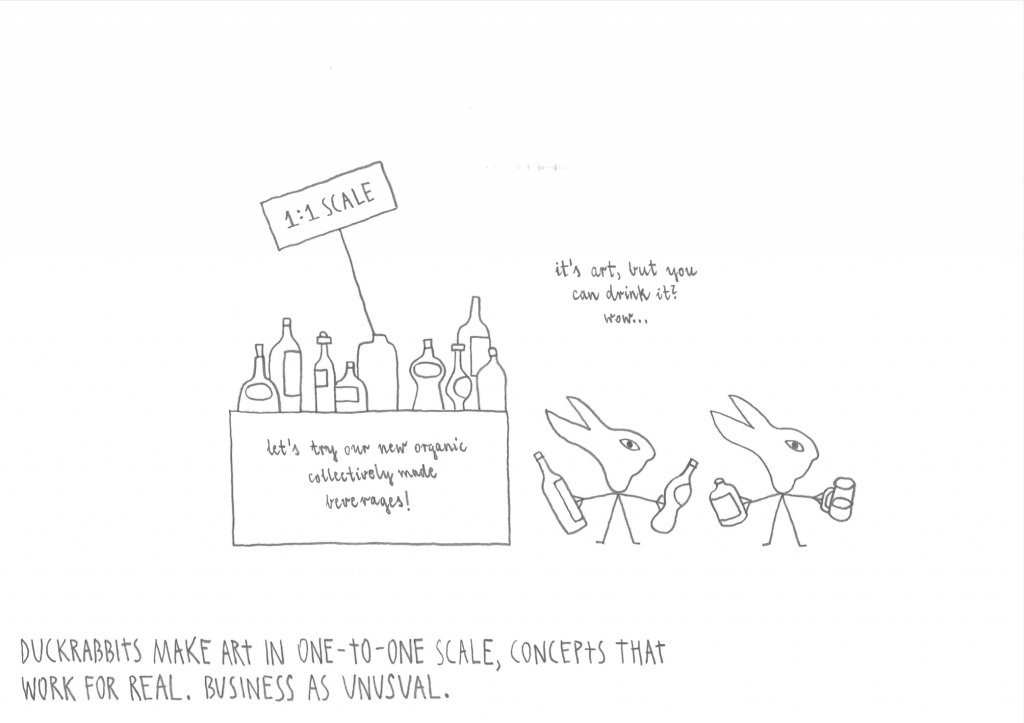

A page from ‘Duckrabbits Revealed: A Sneak Peek at the Postartistic Theory and Practice’, a comic by Kacper Greń illustrating the lecture by Kuba Szreder.

In ‘Duckrabbits Revealed’, the opening lecture of Konteksty 2024, Kuba Szreder expanded on the theory and practice of postart by telling the story of the duckrabbit. The previously imaginary species of duckrabbits was born as an ambiguous image and grew into the spirit animal of postart. According to the perspective and mindset of the observer, a duckrabbit can be recognized either as a rabbit or as a duck. This hybrid nature makes it hard for authoritarians to hunt or pin down duckrabbits. Meanwhile, duckrabbits survive in the wild by feeding on the crumbs of crumbling cultural institutions or piggybacking whatever institutional infrastructures still function. The duckrabbit works outside art studios, although it sometimes comes back inside to seek shelter from the rain. Operating beyond the notion of artistic genius, but infusing its practice with a high ‘coefficient of art’, the duckrabbit creates art on the scale of life. It loves to cooperate, circle, flock, and build patainstitutions together. Therefore, Szreder concluded, you can become a duckrabbit too!

What Is Postartistic Practice?

Postartistic practice is recognizably the product of a scene, which is to say, a socio-cultural group that shares spaces, practices, and ideas, mostly in Warsaw. It is organized more or less centrally around the patainstitutions Consortium for Postartistic Practices (since 2016) and the Office for Postartistic Services (since 2021). The scene also keeps its own Duck Rabbit Archive, which testifies to the diversity of postartistic practices. (If you’re interested, I highly recommend spending a few hours exploring it!)

Some postartistic activities are overtly political. For instance, in Strike Paintings (2018-2024), the artist Arek Parasite went to public protests and pickets carrying artworks as protest signs. And during the 2021 annual antifascist street party in Warsaw, a postartistic delegation took part as an anti-xenophobic Hospitality Block, carrying flag poles with silver and golden emergency heat blankets. Since then, Golden Flags have become a symbol of solidarity with refugees.

Strike Paintings at the 2018 Women’s March in Toruń, Poland.

The March of Hospitality, part of the antifascist street party 2021 in Warsaw, Poland.

Other postartistic practices focus on contemplation, community, refuge, and research. This strand of postartistic practice was best represented at Konteksty 2024. For instance, I was initially surprised at the amount of participatory, delirious performances at the congress. For the piece Heavy Eyes, artists Eliza Chojnacka and Martix Navrot laid out a beautiful table with fresh foods (coming from The Netherlands, it’s an incredible treat to get some real, tasty tomatoes), inviting the audience to sit together, to eat, to relax, and to dive into a collective state of hypnosis. On the next day, Alicja Czyczel, Bartosz Jakubowski, and Jagna Nawrocka of the Queer Academy of Movement performed Viva La Galareta, a bacchanal involving intuitive dance, live poetry, the cooking of jelly pudding, and the eating of strawberries. These experiences made more sense than I could have imagined. As it turns out, even – or especially – when crises stack up higher than we could have imagined, postart can obliterate the temporal distance of 2,500 years (‘cultural tradition’) and create a primal social bond of communal ecstasy.

Preparations for Heavy Eyes by Eliza Chojnacka and Martix Navrot.

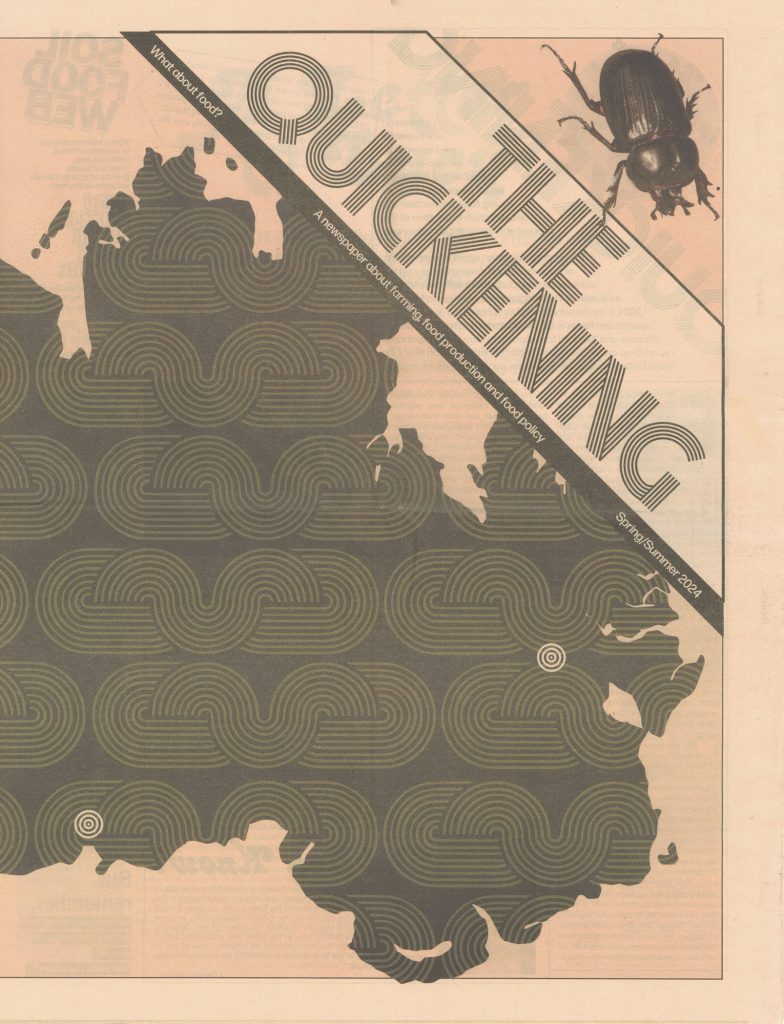

Postartistic Swamp-Work

Since Konteksty 2024 focused on ecology, many activities picked up on the promise of ‘the Sustainment’ as the new Enlightenment. (This, of course, reflects the postartistic practitioners’ desire to improve the relation between humans and more-than-human actors, but also the fundamentally unsustainable art economy.) A highlight was the screening of Deidre O’Mahony’s film The Quickening. O’Mahony organized dinners with Irish farmers, politicians, and agriculture scientists, recorded the conversations, and recomposed fragments into a beautiful, smart libretto. The words were then sung by traditional Irish folk musicians and accompanied by video footage of Irish farm life, alternating between beautifully labyrinthine and realistically harsh. The result is not a film about farm life or a utopian allegory. Instead, the artist, the farmer, the politician, and the soil speak with, against, and through one another, using real words, and presenting real interests and feelings. The film uses artistic cunning to show the actors as they are: entangled in the same, complex reality.

The Quickening takes on various formats, including the film screened at Konteksty 2024 and a newspaper.

The day after the screening of The Quickening, architecture studio Centrala facilitated We Live at the Bottom of an Ocean of Air, a LARP with forgotten weather phenomena for characters (I got to play a lunar corona). With live cloud portraiture, on-site water flow analysis, and the recital of climate data from the nearby weather station, it brought the ecological questions back to the swamp of Floating. It set me thinking that the swamp itself, being a hybrid system of land and water, was a perfect analogy of postart: a hybrid of contradictory elements, advancing or retreating in response to the climate, which strict categories cannot define, but nonetheless gives rise to new imaginaries, practices, and forms of living together.

Centrala’s climate walk and LARP. Full title: ‘We live at the bottom of an ocean of air. We are immersed in water in its gaseous state, in matter that is in a constant state of flux.’

Live cloud portraiture. The idea of the sky as an ocean of air (‘Luftmeer’) was coined in the 1820s by Goethe in the ‘Physikalische Vorträge’.

We Live at the Bottom of an Ocean of Air was followed by a ‘polyvocal dialogue’ between two collectives working in swamps elsewhere. The artist duo Ana Vogelfang and Julieta García Vazquez created the Occasional Museum of an Incredible Landscape on the Clucellas Island in the Argentinian Paraná River; the collective ZAKOLE maps, cares for, and intervenes in Zakole Wawerskie, an extensive, inaccessible meadow in the heart of Warsaw. ‘Both Isla Clucellas and Zakole Wawerskie are wetland ecologies and hybrid habitats with significant biodiversity and environmental importance, constantly threatened by extractivist practices such as landfills for urban development or intentional fires to clear land for monocultures.’ The conversation showed that postartistic swamp-work at Isla Clucellas, Zakola Wawerskie, or Tempelhof is not (just) a local or site-specific phenomenon, but a translocal strategy of resistant cohabitation and post-digital back-to-earth-ness. Thanks to these contributions, Konteksty 2024 became an occasion to dwell in and learn from the swamps of postart.

The polyvocal dialogue between Ana Vogelfang, Julieta García Vazquez, and ZAKOLE (Krystyna Jędrzejewska-Szmek, Ola Knychalska, Olga Roszkowska).

MOPI on Isla Clucellas during BIENALSUR 2021.

Lessons from Postart

So, what is to be learned from the swamps of postart? Postartistic practice emerged in Poland after right-wing populists took power, just like Wilders’s recent rise to power in The Netherlands, Meloni’s in Italy, Le Pen’s in France, and so on. What can practitioners in these places learn from postartistic ambivalence? As the radical right is losing power in Poland, we will soon be able to see how effective the years of infrastructural critique under crisis have been, and what can grow from it. Based on the experience of Konteksty 2024, I can imagine the development of postartistic practice in two contradictory (although not mutually exclusive) directions.

The first is a return to art art. An important trait of postartistic practice is the strategy of ambivalence. It switches between art and nonart, institutional and informal organization, political action and refuge. This ambivalence has allowed for the coexistence of anti-capitalist and liberal agendas (united against conservative and populist nationalism), the militant politicization of art and a timid retreat into private circles, criticality and commerce. This has been a strength so far but might become a weakness. As the situation in Poland ‘normalizes’, public and private money flows resume, and conventional art institutions regain the power to subsume postartistic ambivalence. While pleasurable, secluded gatherings at Floating might or might not continue (it doesn’t matter), the collective agency of postartistic patainstitutions might dissolve into a set of common stylistic traits shared between individual art practices.

A page from ‘Duckrabbits Revealed: A Sneak Peek at the Postartistic Theory and Practice’, a comic by Kacper Greń illustrating the lecture by Kuba Szreder.

However, postart is more than a local form of artistic crisis management. There is another direction that I can just as well imagine postart developing in. The duckrabbit’s art on the scale of life is a direct translation of the avant-gardist desire, described by Peter Bürger, to synthesize art and daily life. This desire has, of course, never been fully gone. But after surviving the postmodern ‘crisis of the new’ in the 1990s and 2000s, heralded by authors like Frederic Jameson, and despite reasonable calls on art workers to desert from the culture wars, a Brave New Avant-garde has risen to politicize art with a renewed and refreshing energy.

While postartistic practice took off in Poland, establishing self-organized patainstitutions and piggybacking existing infrastructures, many other places also saw the rise of prefigurative practices: the Museum of Arte Util, lumbung, Plausible Artworlds, the Arts Collaboratory, L’internationale, the Institute of Radical Imagination, and so on. These diverse instances of what we might call ‘third-wave institutional critique’ share an affirmative critical stance towards institutions and power. They turn not just art, but also curating and institution-building into forms of social practice. I, therefore, find that the aptest description of this movement is Marina Vismidth’s notion of infrastructural critique.

Postartistic practice might just be an important part of this international effort to make the systems of art circulation more sustainable for every actor entangled in its complex, messy reality. Starting from the question, ‘Are we ready to move on?’, Konteksty 2024 showed what life and (post)art could look like on the other side.