“One must speak for a struggle for a new culture, that is, for a new moral life that cannot but be intimately connected to a new intuition of life, until it becomes a new way of feeling and seeing reality.” – Antonio Gramsci

The fact that during the Trump era memes were claimed by the alt-right, with Pepe the frog as its ultimate symbol, resulted in the assumption that the left supposedly cannot meme. Well… it can. Left progressive activist subcultures from all over the world are currently challenging oppressive international and local political discourses with memes in various ways – from anti-racism and free Palestine movement memes to memes about sex (work) positivity, feminism and gender, as well as anti-capitalism and climate activism memes.

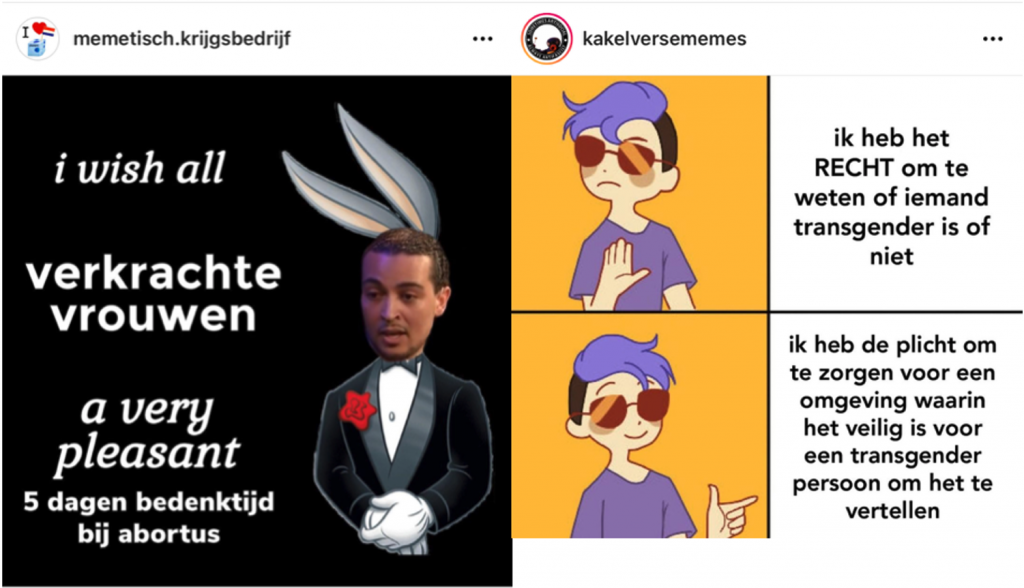

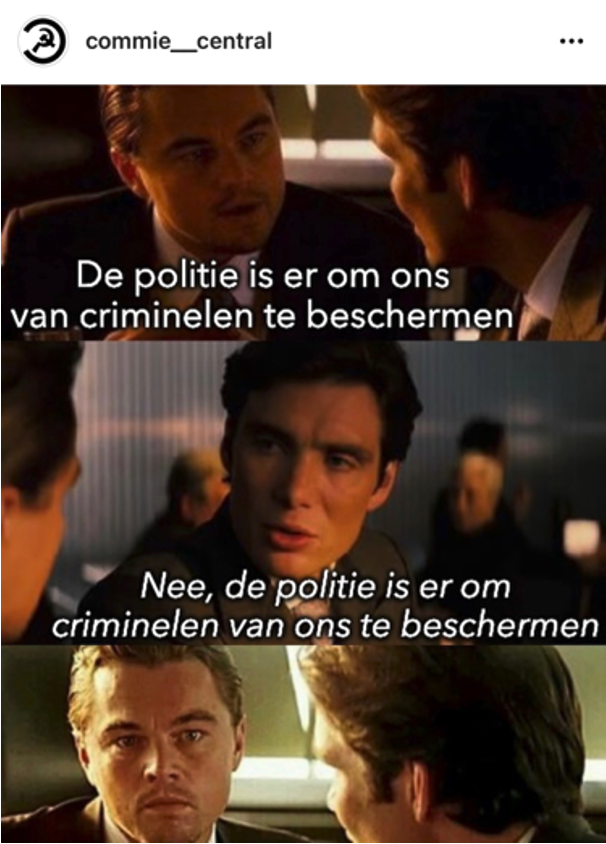

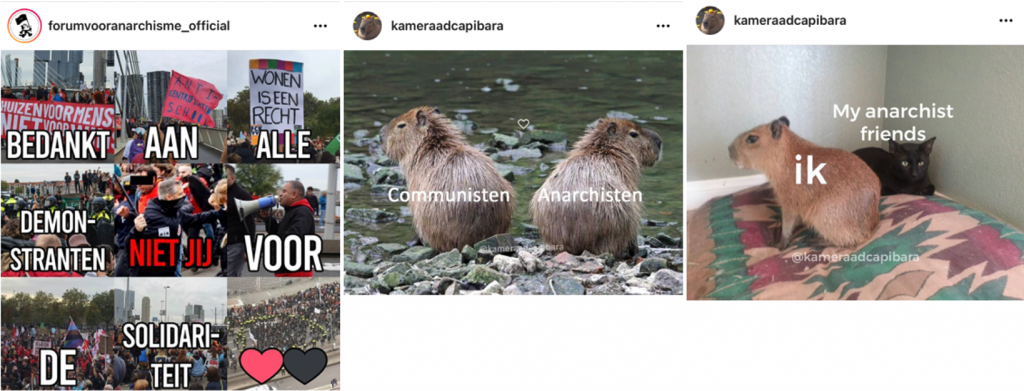

Just look at Instagram meme accounts such as @kakelversememes, @commie__central, @linksinhetnieuws, @politieke_jongeren, @memetisch.krijgsbedrijf, @forumvooranarchisme_official, @gratis_saaf_voor_iedereen, @kamaraadcapibara and @memesvdmassa. They perfectly illustrate the mechanisms behind the progressive left that is countering oppressive discourses with memes, specifically in Dutch politics.

The Left Can’t Meme?

Andy King perfectly illustrates what happened during the ‘Great Meme Wars of 2016’ in her article about far-right tactics in memetic warfare in the Critical Meme Reader. She explains that during the Trump era, the alt-right managed to capture the attention of younger generations with dank memes, controversy and networked adventure, filling the void left by multiple financial crises and social disintegration. According to her, the left was placed in the position of an out-of-touch academic defender fighting to protect remaining online territories, instead of seizing and subverting new grounds. This is crucial, because, as King states, the left currently finds itself in the contradictory position of being referred to as ‘the establishment’ while not having the powers that come with actually being one. Indeed, the alt-right has created a toxic environment on platforms such as Reddit, as Adrienne Massanari mentions – according to her Reddit implicitly reifies the desires of certain groups (often young, white, cis-gendered, heterosexual males) while ignoring and marginalizing others, resulting in harrasment. Platforms such as 4Chan and the anonymity they provide are no expectation of this.

King states that progressives have sheepishly acknowledged the political power of memes but still fail to accommodate their production mechanisms and develop countermeasures.The left can meme, though. King rightfully states that it takes less time to manufacture an endless stream of far-right symbols than it does to identify, analyse, detect, and remove them. Automating the process by building bots to flag online hate speech is not a sustainable solution. However, she states that the far-right fears losing control over symbol creation, which is precisely what the progressive left has been doing; fighting symbols with symbols. In that sense, I agree with Mike Watson, who in his book Can the Left Learn to Meme? states that somewhere in the ‘everything’s going to hell in a handcart’ negativity there is reason for positivity.

Counter Narratives

Anahita Neghabat explains in Ibiza Austrian Memes: Reflections on Reclaiming Political Discourse through Memes, another article in the Critical Meme Reader, that mainstream media often produce hegemonic, sexist, racist, classist or otherwise marginalizing and violent views, by uncritically reprodroducing problematic arguments, generalizations, and vocabulary in an effort to report ‘neutrally’ (illustrated in the meme in Fig.1 ). Neghabat deliberately uses memes herself to intervene in public discourse. She uses memes as her method because memes are simple enough to reach a broad audience, yet at the same time are sufficiently sophisticated to stimulate critical thinking. This connects to what Limor Shifman calls political participation; according to him memes are a mode of expression and public discussion, where any major (political) event has generated a flix of commentary memes the past couple of years. Memes can confront oppressive discourses by presenting alternative interpretations and narratives in an educational context. Neghabat conitines by stating that memes serve a special function for marginalized communities because memes are characterized by their do-it-yourself-aesthetic – anyone can produce a meme with basic editing skills and internet access. According to her the regular occurrence of what would elsewhere be considered spelling mistakes and references to pop culture and entertainment media are all part of the meme’s ontology. Because of this, in combination with their humorous nature, memes must be understood as a tool to reject the whole logic of exclusive, elitist, top-down knowledge production commonly performed by hegemonic, established media and political institutions. As Shifman states; political memes are about making a point – participating in a normative debate about how the world should look and the best way to get there.

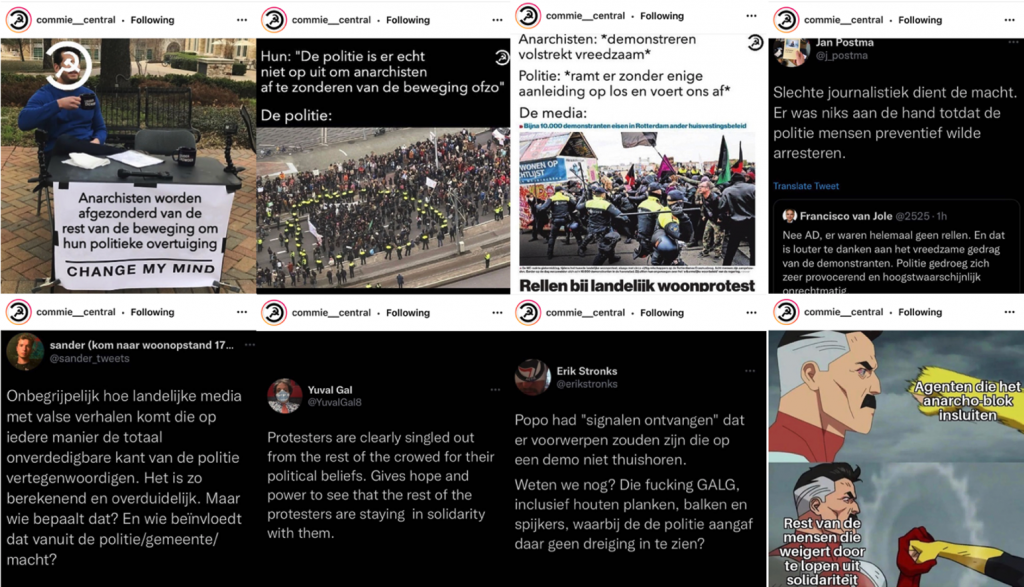

An example of how memes can work as a counter narrative to oppressive mainstream media is presented in Fig 2.1 – 2.8, that capture an Instagram post that consist of of memes and Tweet screenshots by @commie_central, a meme page that comments on political developments from a Marxist point of view. The post is about the police violence that occurred during a protest on the 17th of October this year against the current housing market in the Netherlands. The police and mainstream Ducth media stated that they had reasons to believe that a group of protesters was about to act violently and that is why they had to step in. Protesters that were present showed proof of the police being the ones to start the riot and using a disproportionate amount of violence for protesters that were protesting peacefully. Protesters were let go after they were arrested because the police had no legal reason to keep them there. Nowhere in the media it was mentioned that the police singled out the anarchist protesters, which were then supported in solidarity by the other protesters. Fig. 3.1 – 3.4 show examples of that every meme page I mention commented on this situation, in one way or another.

Fig. 1: Meme by @kakelversememes where SpongeBob represents ‘the media’ and is feeding sleeping Octo a baby bottle of milk who represents ‘right wing (extremist) movements and leaders’.

Fig 2.1: A meme stating ‘Anarchists are being singled out from the rest of the movement because of their political beliefs. Change my mind.’

Fig. 2.2: A meme with the text ‘Them: ‘The police is not out to single out anarchists from the movement or something. The police:’ with a picture of the police literally singling out the black block of anarchist protesters.

Fig 2.3: Meme with the text ‘Anarchists: *protest completely peacefully*. Police: *Starts hitting us without any reason and arrests us*. The media: Riots at protest.’

Fig 2.4: Tweet screenshot saying ‘No, AD [which is a Dutch news paper], there were no riots. And that is solely because of the peaceful protesters. The police acted very provocatively and probably illegally.’ and ‘Bad journalism serves those in power. There were no issues until the police preventively started to arrest people’.

Fig 2.5: Tweet screenshot saying ‘Incomprehensible how Dutch media present false stories that side with the police who are completely indefendible. It’s so calculating and clear. But who decides this? And who influences this from the police/city council/power?’.

Fig 2.6: Another Tweet screenshot.

Fig 2.7: A Tweet screenshot saying ‘The police ‘received signals’ that there would be objects that do not belong at a protest. Do we remember that f*cking gallow, including wooden planks and nails, where the police said to not indicate a threat’, alluding to a protest against the covid legislation in the Netherlands on the 3rd of October where people brought a gallow.

Fig 2.8: A meme with the text ‘Cops that single out the Anarchists’ and ‘The rest of the protesters who refuse to continue because of solidarity’.

Fig. 3.1: @kameraadcapibara (translates as ‘comrade capybara’), a communist meme page that makes memes solely with capybaras, showing a meme where a caged capybara is being loaded into a truck with the caption ‘Police officer who ignores the right to peacefully protest and arrests me – Me, a peaceful protester’.

Fig 3.2: @gratis_saaf_voor_iedereen showing a meme with various images of police violence during the protest in Rotterdam with the text ‘the police is here to protect us’. Fig 3.2: @kakelversememes showing a meme that says ‘*peaceful demonstration* Rotterdam police:’ with a picture of a police officer ready to use a weapon.

Fig 3.4: @linksinhetnieuws (translates as ‘leftist news’) showing a meme where the kid asks ‘why are there so many homeless people on the streets?’ and the dad answers ‘In the Netherlands making profit on housing is more important than human lives’. The meme end with them hugging and the text ‘Fuck you VVD’, which currently the biggest right wing and most influential party in the Netherlands.

Dialectical Seeds for Change

A valid argument that could be made at this point would be that these progressive left memes are stuck in their own activist bubble. In her essay King states that leftist memes are still primarily created by leftists for leftists, without a methodical branching out to adversaries, while the alt-right excels at conquering new territories by invading not only politically neutral online spaces, but also those belonging to their opponents. Indeed, as Daniel de Zeeuw and Marc Tuters mention, memes are often intentionally obscure to those outside the in-group. Political leftist memes do seem to be created for and consumed by a very specific progressive audience that is already interested in and has a certain amount of knowledge about politics and left topics. However, the left actually is actively reaching out beyond its own echo chamber, perhaps in a more subtle way than the alt-right.

In an interview that political meme admins Anahita Neghabat and Jamie Brands discuss how their memes reach outside of their progressive bubble. They point out that their memes often influence those who see themselves as apolitical or politically neutral and that their memes circulate in WhatsApp groups of older ‘boomers’ who usually have a more traditional political ideology. They also discuss that even though memes have various complex levels of symbols and meanings, they are usually also simple enough to be understood, even for those who are not extremely left wing or politically active.

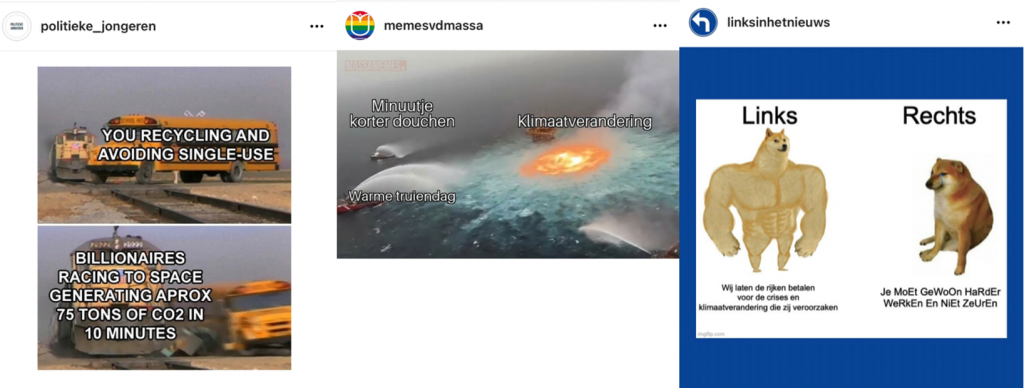

In this way, leftist memes plant what I like to call ‘dialectical seeds for change’, as an hegemonic culture war tactic, to slowly change dominant views and norms. In their essay Rude Awkwaning: Memes as Dialectical Images, Geert Lovink and Marc Tuters illustrate, using Walter Benjamin, how memes can be seen as dialectical images. According to them, memes can be seen as cultural negotiations that take place in the flow of everyday language, where meaning is not authoritatively established. Tutors and Lovink compare Benjamin’s metaphors on awakening, transformation and the hope for insight with meme processes. They state that even though memes are inherently ironic, they can also purport belief. Wanting to wake people up with memes, is something that the alt-right and progressive left seem to have in common, Lovink and Tutors point out. The progressive left is excellent at making memes that show alternative sides of stories of dominant oppressive discourses in a subtle and dialectical way. Memes that make those who see them go ‘I never thought of it like that’; planting a seed for a change of ideology, or awakening. Exemples of this in the context of climate change, the Zwarte Piet (Black Pete) debate, abortion, transgender safety and police violence are llustrated in the following examples in Fig 4-7.

Fig 4.1: Meme by @politieke_jongeren (translates as ‘political youth’) making the comparison for why it is unfair to make humanity responsible for solving the climate crisis with recycling and avoiding single use products, while billionaires are racing to space.

Fig 4.2: @memesvdmassa making the same point. In this meme the fire in the ocean represents climate change and the boats trying to kill the fire with water which is happening in water with showering a minute shorter or wearing a sweater instead of turning up the heating in your home.

Fig 4.3: Meme by @linksinhetnieuws where the left says ‘We should let the rich pay for the crisis and climate change they are causing’ and the right says ‘YoU jUsT hAvE tO wOrK hArDeR aNd StOp WhInInG’.

Fig 5.1: Meme by @kakelversememes saying ‘Black Pete is black face and normalizes racism’, ‘Ah, come one, it is only facial paint, don’t be so sensitive about it’, ‘Ok, so you don’t mind if we change it then?’, ‘How dare you’.

Fig 5.2: Meme by @kakelversememeswhere Michael Scott from the television show The Office has a conversation with The Netherlands. The dialogue goes as follows; ‘You are known for..’, ‘Tulips and windmills?’ ‘The first country to legalize gay marrige?’, ‘Weed, the red light district and that racist black face kids party’.

Fig. 6.1: Meme by @memetisch.krijgsbedrijf that says ‘I wish all raped women a very pleasant 5 day reflection period for an abortion’ alluding to the law in the Netherlands where you have to wait five days when you want to have an abortion.

Fig. 6.2: A meme by @kakelversememes, rejecting the text ‘I have a RIGHT to know wherether someone is transgender or not’ and approving the text ‘I have the duty to create a space where it is safe for a transgender person to tell us’.

Fig. 7: Meme by @commie__central. The dialogue translates as ‘The police are there to protect us from criminals’ and ‘No, the police are there to protect criminals from us’.

A Sense of Solidarity and Unity

The progressive left does not only offer counter narratives and dialectical seeds for change, they also offer something the alt-right does not; solidarity. King states that the alt-right does not offer psychological support even to its most ardent members. Anahita states that the humor in memes for the progressive left is part of a collective empowerment strategy to build resilience through a process of self-affirmation. She states that humor is a deeply subjective and intimate experience and therefore finding something funny together creates a sense of intimacy and community – sharing one’s discomfort and dealing with negative experiences offer emotional relief and support. Sharing a meme that makes you both want to laugh and cry with a fellow lefty is a feeling many of you might recognize.

Memes do not only offer solidarity, they also unify. King states that one of the reasons for the alt-right’s success is that they embrace ideological differences, creating an army of athists, harcore Christians, gay white supremacists and homophones fighting side by yes. Indeed, the progressive left may be fragmented and critical of each other, however, memes are an active tool unifying different communities here as well. Various groups come together and set aside their differences for the greater good. An example is communists and anarchists meme makers showing solidarity regardless of their ideological differences after the earlier mentioned police violence that happened in October, shown in Fig 8.1-3.

Fig 8.1: Meme by @forumvooranarchisme_official (translates as forum for anarchism) thanking the other protesters for their solidarity.

Fig. 8.2: Meme by @kameraadcapibara, showing the love-hate relationship between communists and anarchists (on Instagram).

Fig 8.3: Meme by @kameraadcapibara showing solidarity to the anarchist community regardless of their ideological differences. The capybara represents ‘me’ and the black cat represents ‘my anarchist friends’.

Tactical Effects Beyond the Virtual Image

We can all agree now that local oppressive political discourses are actively being challenged by various Dutch progressive leftist meme accounts in various ways. The question that remains then is, how are these memes contributing to actual tactile change beyond the virtual image?

Shifman explains that memes can function as grassroots for action by linking the personal and the political to empower coordinated action by citizens. In the same interview Neghabat and Brands discuss that, although they acknowledge that this is hard to measure, both of them have seen tactical effects of their meme activist practices. They have influenced numerous followers to vote for progressive left wing parties, they are regularly in contact with politicians and journalist who ask for advice, they play an active role in connecting and unifying various left wing organizations who remain otherwise fragmented and receive countless messages from young people that tell them that their memes got them engaged in politics – as Shiftman also states that memes offer various ways to stimulate political activity, especially with younger citizens who are least likely to participate in formal politics.

Let’s end this with a speculative suggestion. The fact alone that Pepe can be reclaimed into a completely different political context by protesters in Hong Kong, as Caspar Chan illustrates in the Critical Meme Reader, shows that the left can already meme and that nothing is set in stone. Anirban Baishya describes – once again in the Critical Meme Reader – how memetic logic can move beyond the virtual into the real world. He takes the Blue Whale challenge, a morbid and illusive game where players supposedly have to fulfill a number of taks, with the last task being suicide, causing mass hysteria in India without there ever being proof of the game, as an example. He calls this ‘memetic terror’ and describes it as “an affective, networked fear of breaching. It replicates itself through exposure to repeated information, reverberating throughout digital infrastructures, as it interacts with personal devices, policy, and regulation, as well as users’ bodies”. Now, imagine, if the same logic was applied to spread progressive ideas for a possible future. As King notes; “memetic warfare is more immediate and accessible than real-life demonstrations. It is not susceptible to police disruptions and pandemics. If anti-fascists build an active online presence, they can assimilate enough supporters to demote the alt-right.” Watson states that millennials refuse to surrender to cynicism and populism and choose to weird-out the world, and perhaps this is a naive take, but if memes can help the alt-right to mobilize people to storm the Capitol, the left should be able to do the same to spark a revolution. It still remains a fact that memes are used by the alt-alt right and that what Massanari calls “toxic technocultures” is a dangerous phenomenon. Perhaps this issue is a nuanced one, where both Shifman and Neghabat and Massanari and King are right. When Watson asks whether it would be possible to see [memes] as both positive and negative simultaneously, the answer is yes, and that besides the legitimate cause for worry, the progressive left offers hope as well.

Works Cited

Baishya, Anirban. “It Lurks in the Deep: Memetic Terror and the Blue Whale Challenge in India.” In Critical Meme Reader: Global Mutations of the Viral Image, edited by Chloë Arkenbout, Jack Wilson and Daniel de Zeeuw, 248-260. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2021.

Chan, Caspar. “Pepe the Frog Is Love and Peace: His Second Life in Hong Kong.” In Critical Meme Reader: Global Mutations of the Viral Image, edited by Chloë Arkenbout, Jack Wilson and Daniel de Zeeuw, 289-306. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2021.

King, Andy. “Weapons of Mass Distraction: Far-Right Culture-Jamming Tactics in Memetic Warfare.” In Critical Meme Reader: Global Mutations of the Viral Image, edited by Chloë Arkenbout, Jack Wilson and Daniel de Zeeuw, 198-216. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2021.

Lovink, Geert and Marc Tuters. “Rude Awakening: Memes as Dialectical Images.” Non Copyriot, April 2, 2018. https://non.copyriot.com/rude-awakening-memes-as-dialectical-images/.

Massanari, Adrienne. 2016. “#Gamergate and the Fappening: How Reddit’s Algorithm, Governance, and Culture Support Toxic Technocultures.” New Media & Society 19 (3): 329–46.

Neghabat, Anahita. “Ibiza Austrian Memes: Reflections on Reclaiming Political Discourse through Memes.” In Critical Meme Reader: Global Mutations of the Viral Image, edited by Chloë Arkenbout, Jack Wilson and Daniel de Zeeuw, 130-142. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2021.

Neghabat, Anahita and Jamie Brands. “Challenging Oppressive Discourse in Local Politics with Memes.” Interview by Chloë Arkenbout. Global Mutations of the Viral Image: Critical Meme Reader Launch, Institute of Network Cultures, October, 07, 2021. Video to be published.

Shifman, Limor. 2014. “May the Excessive Force be With You: Memes as Political Participation” in Memes in Digital Culture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Watson, Mike. Can the Left Learn to Meme? Adorno, Video Gaming and Stranger Things. Winchester: Zero Books, 2019.

de Zeeuw, Daniël, and Marc Tuters. 2020. “The Internet Is Serious Business: on the Deep Vernacular Web and Its Discontents.” Cultural Politics 16 (2): 214–32.

This essay was based on an assignment that was handed in for the New Media Theories course, which is part of the New Media and Digital Culture MA program at the University of Amsterdam.