“I am no longer accepting the things I cannot change. I am changing the things I cannot accept.” ― Angela Davis

“For the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us to temporarily beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change.” – Audre Lorde

Do you know that feeling, when you are trying to explain your valid experiences to an ignorant privileged person who has no idea? If you are part of a marginalized group in society, like me, you probably do. You stay calm because otherwise they will feel personally attacked and will stop listening to you. Frustrating, isn’t it? It feels unreasonable to be reasonable. In an attempt to create more understanding, marginalized groups seem to be stuck in their own moral values, causing them to oblige to existing oppressive power structures, instead of breaking them. And while it is definitely a noble goal, and the amount of restraint is admirable, there feels something deeply wrong with having to be the one to stay nice, while explaining to your oppressor your human rights. And frankly, it makes me angry. This power disbalance is reflected perfectly in online public debate, in endless discussions in social media comments. Here, marginalized groups are forced to be polite, in order to have a slight chance to be taken seriously. How are marginalized groups forced into this paradox of this nonviolence in online public debate exactly?

Before I continue, I find it incredibly important to make clear that I speak from an intersectional intention. I use decolonization theory, antiracism theory, queer theory and feminist theory interchangeably, even though these all have different contexts. When I talk about Black people, women and queer people, their struggles represent the same struggles that other marginalized groups face. I am aware of the fact that these groups face specific problems (and that there are a lot of other people that are also marginalized) and these should be researched accordingly. However, for the sake of unity, when I talk about oppressed groups, marginalized people, I mean all of them, I mean all of us.

The semantics of (non)violence

First things first; let’s dive into (non)violence. One of the most famous humans to advocate for nonviolence was, of course, Gandhi. He said that “we may never be strong enough to be entirely nonviolent in thought, word and deed. But we must keep nonviolence as our goal.” Another iconic figure in history in favor of nonviolence was of course, Martin Luther King. He thought that nonviolence was the most potent weapon for Black people during the U.S. Civil Rights Movement and for other oppressed people around the world. For King love was the most powerful force in the world, and for him, nonviolence was love expressed politically. Love your enemy, do not destroy them, but make them your friend, he said.

As James Cone continues to explain, Malcolm X directly criticized King and saw nonviolence as a ridiculous philosophy. According to him, self-defense is an essential element in the definition of humanity. He thought that Black people should use any means necessary to get their freedom. Someone who also cannot remain undiscussed in this context is Franz Fanon, who wrote about violence in the context of decolonization. For him, decolonization was the meeting of two forces, opposed to each other by their very nature marked by violence. He explains that nonviolence leaves oppressors intact. For Fanon, violence unifies the people and that “at the level of individuals, violence is a cleansing force. It frees the native from his inferiority complex and from his despair and inaction; it makes him fearless and restores his self-respect.”

A more current take on (non)violence is that of Angela Davis. She states that the only reason there are violent revolutions is that our society, which is determined by those in power, is violent. Davis calls for a paradigm shift, where we challenge our pre-existing biases, towards a world free of violence; that is, a world free without racism, capitalism, white supremacy, homophobia and all systems of oppression.

In her recent book, The Force of Nonviolence, Judith Butler insists on the same thing; our current social structures or systems are violent. Even though many people already live in violent conditions, violence can be seen as resistance, reactive or defensive counter-violence, used as means for a greater goal, Butler calls for a new way to look at nonviolence. She sees it as an ethical practice of resistance rooted in rage.

What I find most interesting about Butler and her views is the fact that there seems to be no general agreement on what constitutes as violence and nonviolence. To argue for or against it, requires a definition, according to her. However, there is “no quick way to arrive at a stable semantic distinction between the two when that distinction is so often exploited”.

Social media comment wars

Howard Caygill states that “any reflection on the contemporary capacity to resist must consider the question of the technology” and that “the internet has become a crucial site for contemporary resistance”. So let’s define what is meant by violence and nonviolence in the context of this new media studies context then. I view the language that is used to fight a war online in social media comments as violence; where oppressors use microaggressions as their weapon of choice and the oppressed are forced to stay reasonable as a form of nonviolence instead of showing their anger.

Butler states that “some people call wounding acts of speech violence, whereas others claim that language cannot properly be called violent”. In this context, I do categorize the language that is used by people who enter the public digital sphere as violent. Because, I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again; language is power.

That power is currently being contested in a Gramscian context. Jan Blommaert explains that the thing that enables the bourgeoisie to remain in power is not just its control over the economic infrastructure and the state – it is its control over the hearts and minds of people. The bourgeois ideology has become normal to most people. Gramsci called this form of ‘soft’ cultural power hegemony. According to Gramsci, all revolutionary movements must gradually change the dominant culture of the people and replace the prevailing ideas, before the actual revolution goes down. This slow process counts on education, the arts and the media. In this case, a culture war is taking place on the level of public debate through social media comments.

The power imbalance in the digital public sphere

However, the oppressed and the oppressors do not have equal positions in this social media comment war. Soraya Chemaly explains that it is important to mention that with anger, the context of that very anger often governs how it can be expressed. According to her, especially for women one of the foremost regulators of their expression is how they are supposed to behave in public, where they are often tone policed, keeping them from being engaged in politics. In online public debate, tone policing is something that often happens to marginalized people. Tone policing is an anti-debate technique in which someone criticizes the way the arguments are presented rather than dealing with the content of the arguments themselves, as Dutch anti-racist activist and writer Chanel Matil Lodik explains. Audre Lorde gives a personal example of this, where she spoke out of direct anger and a white woman told her to tell her how she felt, but not too harshly because otherwise, she could not hear her. Tone policing often goes hand in hand with gaslighting, which is a form of psychological manipulation to make someone doubt their sanity and (white) fragility, the defensive stance many privileged people adopt when confronted with information about radical inequality and injustice, according to Lodik. Apart from trolls, oppressors often do not directly use violent language or threats, but they use more subtle tactics, such as microaggressions, which Lodik defines as consciously and unconsciously offensive, derogatory, hostile comments that are so commonplace that they are barely noticed.

As a consequence of this power imbalance, marginalized people are forced to stay nice, calm, polite, and reasonable while being directly attacked. Jessica Maddox and Brian Creech state that institutions have largely refrained from intervening in the digital public sphere, the burden of ethical engagement has been taken up by individuals. Indeed, the moral responsibility when engaging in nuanced online public debate, where microaggressions are tackled with reason and politeness, seems to lie with the individual commenter and not with the platforms in question.

This power imbalance is dangerous and further marginalized oppressed groups, for the same reasons LeftTuber ContraPoints her tactics for deradicalization alt-righters on YouTube are being criticized. ContraPoints uses a strategy that Mouffe calls agnostic debate, which centers facts, concepts, and lines of argument. In this context, “reasonable debates emerge online if they respond to rather than initiate injustice or threat, push back against an action or event without devolving into personal insults, and remain sensitive to socially rooted contextual standards of judgment.” ContraPoints remains empathic and makes an effort to speak their language, to make sure her oppressors (who often deny her very existence as a trans woman) do not feel attacked. She does not see them as monsters. As King advised, she does not destroy her enemies, she makes them her friend. However, critics have expressed that her work can only be successful if she inserts arguments into preexisting logics that sustain more powerful positions. Maddox and Creech ask whether it is productive to try to appeal to reactionary identities whose arguments are, in part, based on marginalizing vulnerable people? In the context of online public debate, let’s ask ourselves the question of whether to react reasonably and empathically to commenters with oppressive views, even when the goal is to change their mind, is worth it?

The power of collective anger

What if oppressed groups decided to not stay nice though? To choose violence over nonviolence? In Rage Becomes Her, Chemaly researches the power of anger. In line with Fanon his take on violence, she claims that we should be liberating our anger, as “the root of the word aggressive is related closely to the Larin word aggredi, meaning ‘to go forward’”. According to her, it is no surprise that anger infuriates those in power, as it indicates that a woman is not conforming to traditional norms. Lorde also states, in line with Davis, that “it is not the anger that lies between us, but rather the hatred leveled against all women, people of colors, lesbians and gay men, poor people, against all of us who are seeking to examine the particulars of our lives as we resist our oppressions”. Simply by speaking in anger, oppressed groups violate powerful rules because, according to Chemaly, their anger is a strong reminder of social imbalances. Anger is a moral emotion that makes it possible for people to make judgments, and women are supposed to be removed from the authority that comes with that, which is precisely why women should not only have the right to claim anger, it is a moral obligation to do so. When denying anger, women deny their right to use it effectively and appropriately. Anger can help find communities and to create collective social action, as it is a source of energy, joy, humor and resistance.

Collective social action in the digital realm is often organized through counterpublics. Bryce J Renninger states that it is widely acknowledged that the Internet’s possibility for decentralized communication affords the possibility of a networked public sphere. He explains that networked publics are both the “space constructed through networked technologies” and the imagined collective that emerges as a result of the intersection of people, technology, and practice. They allow people to gather for social, cultural and civic purposes, and they help people connect with a world beyond their close friends and family.” He continues by stating that because marginalized groups sit radically outside of the public sphere, they often form their own, smaller public spheres, which are called counterpublics. According to him, counterpublics are constituted through a conflictual relation to the dominant public. “The value of counterpublic communication is rarely recognized, except by those seeking to change the status quo, because it engages in the non-compliant practices of intervening, and the formation of new social and cultural structures, both in support of and resistance to changing social norms and values.” Renninger continues by stating that counterpublics serve two simultaneous roles; they function as spaces of withdrawal and regrouping and they also function as bases and training grounds for agitational activities directed toward wider publics. Counterpublics allow those that lie outside of sanctioned publics to map their own ideologies, thoughts, and subjectivities among people, mostly strangers, that share an awareness.

Microagressions on Facebook

So what happens when marginalized groups that have unified for collective social action leave their safe counterpublics to use their tactics in the wild and put their dialogue skills to the test for a wider public, on a platform such as Facebook? Let’s look at the comments at three different Facebook posts from prominent Ducth newspaper de Volkskrant that discuss identity politics subjects.

An important context for these comments is that social media platforms often create a clickbait media environment, as Juliane A Lischka and Marcel Garz point out in their article about clickbait news and algorithmic curation. According to them, editorial decisions for news outlets are often based on the affordances of the platform in question. Maddox and Chreech also emphasize that news producers play an outsize role in amplifying problematic content, because audiences cohere around affective expressions of identity, and those expressions often gain cultural and financial capital through virality. In the case of Facebook, as with many other platforms, the more engagement (comments) a post has, the more reach a news outlet will have. Posting snappy and controversial headlines about identity politics subjects that will spark discussion is a tactic of news outlets to gain traction.

The following examples come from a pool of countless other comparable comments. A trigger warning for them is in place, as they contain racism, transphobia, xenophobia and misogyny & mysoginoir. In the subjects I chose to study, I took a clear political stance against oppression because I am distinctly antiracist, anti-transphobia, anti-xenophobia and pro-choice. Because as a researcher, it is important to not be neutral and objective about subjects that surround human rights.

Racism in the Dutch parliament

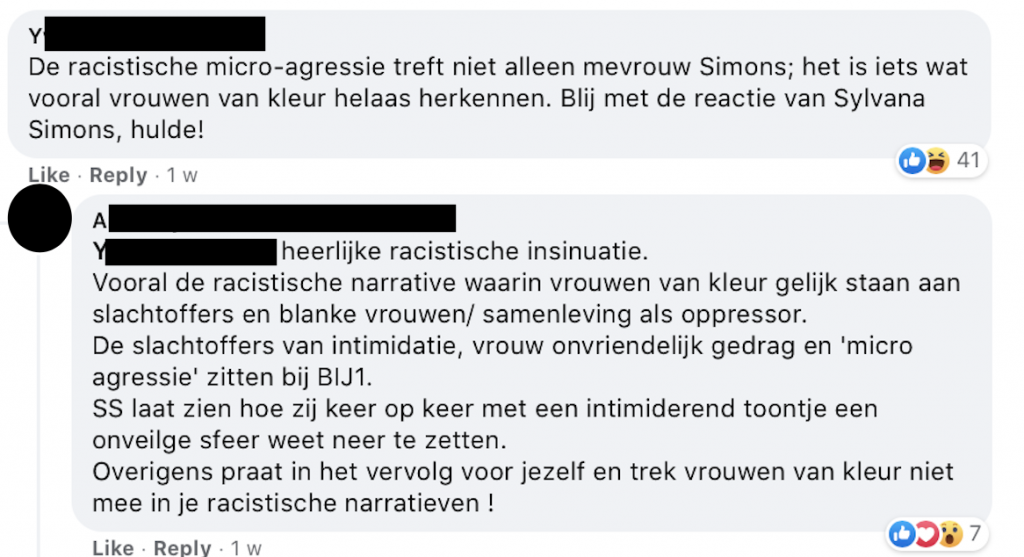

Fig 1. An opinion column about how a right-wing party member was condescending towards Sylvana Simons, the first Black female party leader ever present in the Dutch parliament, after she was threatened during a debate.

Fig. 2.1: B. says that Sylvana was annoying, that she deserved it, and that because of her behavior people will never listen to her even though she might be right. A clear example of tone policing. No one bothers to point out his racism.

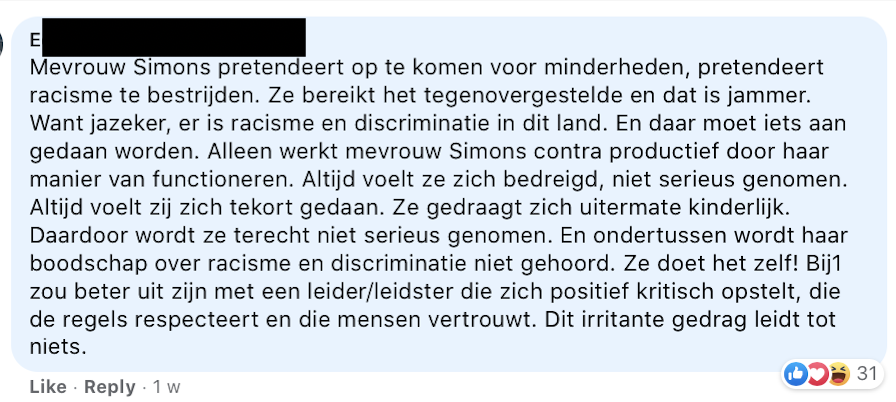

Fig 3.1 – 3.2: E. expresses how Sylvana her childish behavior is not productive, she should be more positive and that she is annoying. M. responds to E. in a polite manner and tries to explain to him that she was literally threatened.

Fig. 4: Y. points out that a lot of Black women and women of color face microaggressions. A. responds with a gaslighting response by claiming that Sylvana is the one who creates an unsafe environment.

Transphobia

Fig. 5: An opinion column about the fact that it is not true that trans people corrupt children.

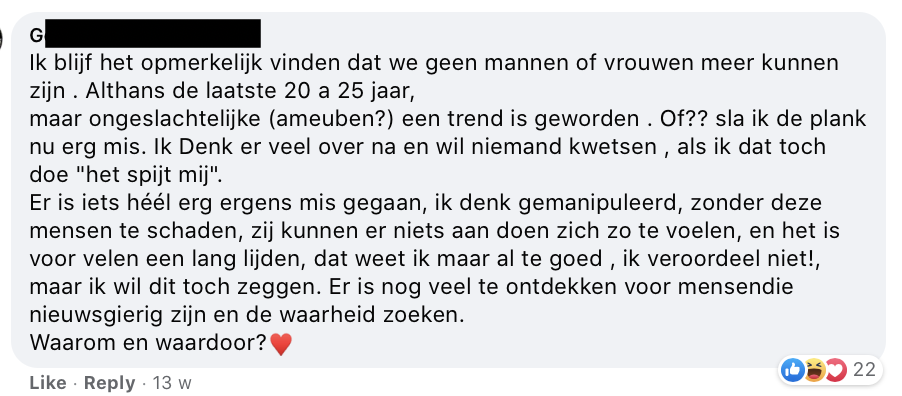

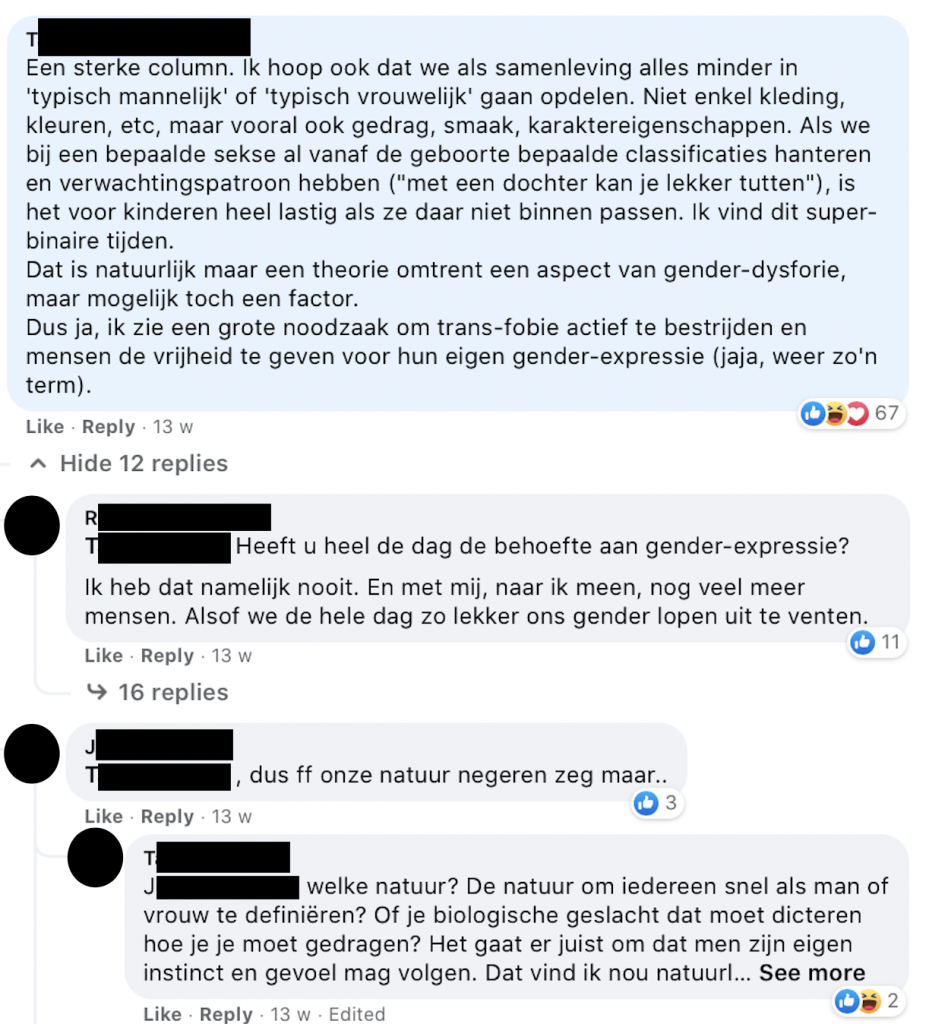

Fig. 6.1 – 6.2: G. makes a hurtful comment about how she ‘does not judge’ because she understands that trans people are manipulated and it is not their fault – another gaslighting example. J. does not call out her transphobia but writes a friendly message about how we should all let people be themselves.

Fig. 7: T. writes an elaborate comment about how the column in question is necessary because we live in a world that is binary and limiting. R. and J. respond with short comments that directly mock T. her argument, after which T. still responds in a calm way, further trying to explain their point.

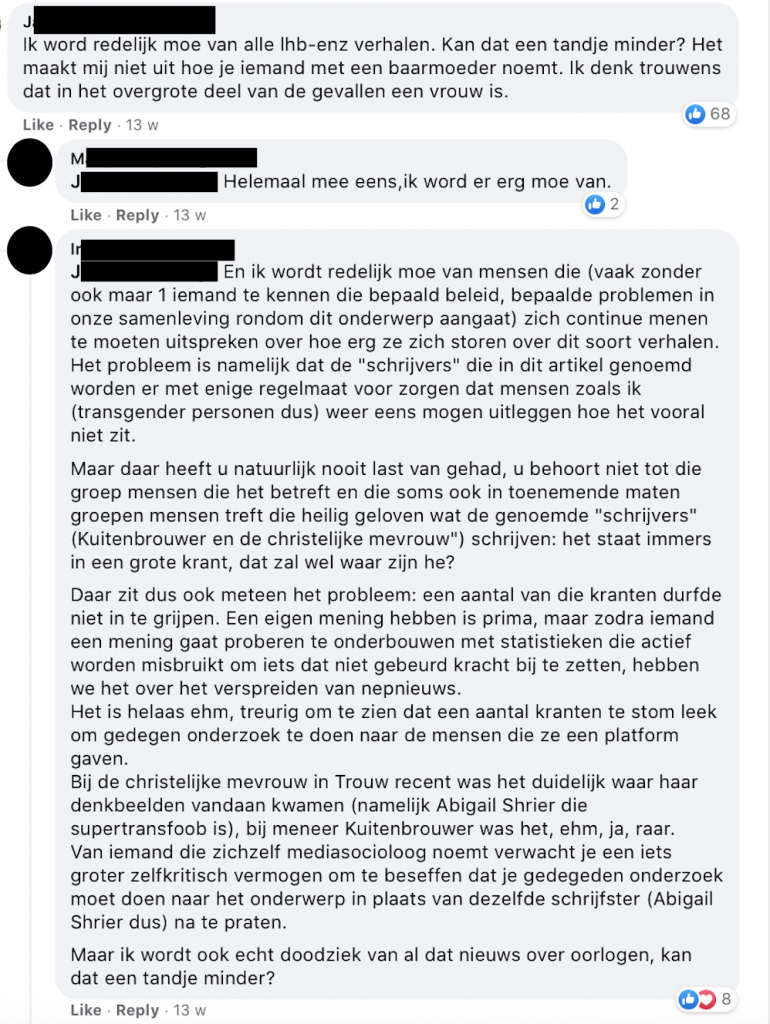

Fig. 8: J. says he is tired of ‘all the LHBT etc stories’, a fragile comment to make. I., who is obviously angry, still tries to make J. understand where she comes from in an extremely elaborate comment.

Xenophobia and anti-abortion

Fig. 9: An article about how people with a migrant background do not have the right to a free abortion procedure in the Netherlands.

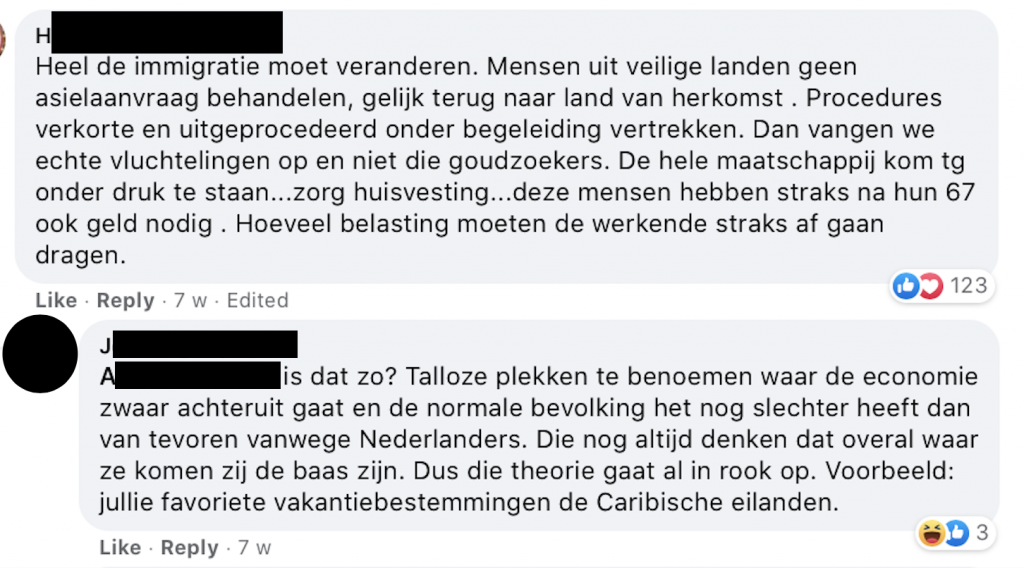

Fig 10.1 – 10.2: H. says that people with a migrant background should go back to their own country if they want an abortion. J. does not call out her xenophobia but tries to explain to her why her argument does not make sense in a respectful manner.

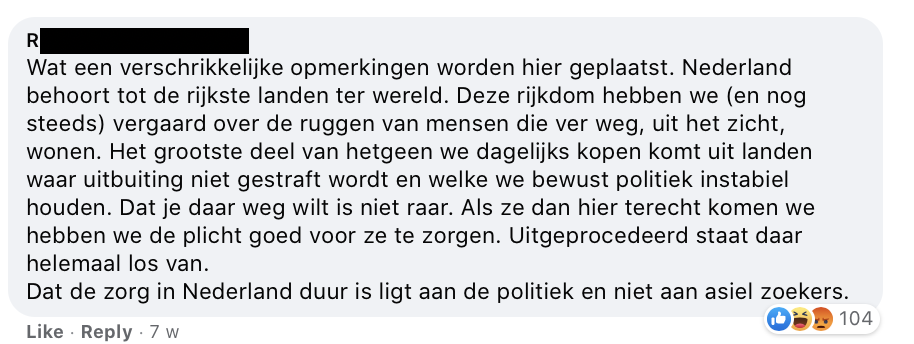

Fig 11.1 – 11.2: R. writes an elaborate comment where he tries to explain why we should always help other people regardless of the country they come from and D. makes a rude comment about how people with a migrant background should just use a condom.

Be a glitch in the platform system

I don’t know about you, but just reading these comments makes me furious. All commenters in the previous examples bend their ways to oppressive commenters who use microaggressions, with a nonviolence approach, which leaves me with a bitter aftertaste. In order to try to change the world for the better and in an attempt to create more understanding, marginalized groups seem to be stuck in their own moral values, causing them to oblige to the existing oppressive power structures, instead of breaking them. In order to break free, to self-actualize and to create a new world, marginalized groups should liberate their anger in online public debate and stop being nice, as an act of glitch feminism, as an act of resistance.

Anger is a social responsibility, according to Chemaly, and I agree; “if anger is poison, it is also the antidote and an act of radical imagination.” However, most women have not developed the tools for facing their anger constructively, according to Lorde. This is because “women of today are still being called upon to stretch across the gap of male ignorance and to educate men as to their existence and their needs. This is an old and primary tool of all oppressors to keep the oppressed occupied with the master’s concerns” – the same logic applies to black women who have to educate white women, queer people who have to educate cisgender heterosexual people, and so forth. Lorde explains that she once lived with her anger in silence, but that her fear of it taught her nothing. According to her, every woman has a well-stocked arsenal of anger potentially useful against oppression and that it can become a powerful source of energy serving progress and change, as it is loaded with information and energy. “We cannot allow our fear of anger to deflect us nor seduce us into settling for anything less than the hard word of excavating honesty.”

How, then, would this translate to the digital realm of public debate? The answer lies in Russel’s glitch feminism. She states that violence is a key component of the patriarchy and that glitch feminism is about wanting a better world and a rejection of the here and now. Even though “’the paradox of using platforms that grossly co-opt, sensationalize, and capitalize on POC, female-identifying, and queer bodies (and our pain) as a means of advancing urgent political or cultural dialogue about our struggle is one that remains impossible to ignore.” Russel explains that “what these institutions—both online and off—require is not dismantling but rather mutiny in the form of strategic occupation”:

“Glitch is an active word, one that implies movement and change from the outset; this movement triggers error. Traversing through these origins, we can also arrive at an understanding of glitch as a mode of nonperformance: the “failure to perform,” an outright refusal, a “nope” in its own right, expertly executed by machine. Glitch moves, but glitch also blocks. It incites movement while simultaneously creating an obstacle. Glitch prompts and glitch prevents. With this, glitch becomes a catalyst, opening up new pathways, allowing us to seize on new directions. It helps us to celebrate failure as a generative force, a new way to take on the world.”

To conclude, let me make a suggestion to all people that belong to a marginalized group and are angry. It is not unreasonable to be unreasonable. Stop being nice. Refuse. Resist. Say nope. Be a glitch in the platform system. Or as Zadie Smith put it when she was contemplating whether to put her thoughts publically into the world and having to be as polite and calm and unangry as possible; “I’ve been thinking, you know, fuck that, basically.” However, I am aware of the fact that for a lot of marginalized people, it is unsafe to stop being polite and show anger, that to stay nice is a means to survive. I see that reality. But it is not fair. I hope that one day, somehow, everyone will be safe enough, radically equal enough, to express their anger. So here I am, trying to contribute to this goal as a white queer woman who is aware of the privileges she does and does not have. I am angry and I will not be forced into political correctness anymore. Are you with me? Who knows, once Gramscian soft power norms start to shift, an actual revolution might take place.

Next steps

Subjects such as free speech, cancel culture, trolling, content moderation & shadowbanning, affect theory (as comments are usually fuelled by emotions), the bystander effect (it was Desmund Tutu who said that “when you stay silent you have chosen the side of the oppressor”) & voyeurism and bias & polarization are other concepts that I will explore next. The influence of the affordances and algorithms of Facebook and other platforms such as Instagram and Twitter, in the context of platform studies, in the form of a cross-platform analysis, and interviews with commenters to gain more insight on their tactics are methods I will also look into.

Works cited

Biography.com. “Gandhi Quotes.” Accessed December 22, 2021. https://www.biography.com/news/gandhi-quotes.

Blommaert, Jan, “Why Gramco’s Ideas are Still Relevant,” Digit Magazine, November 11, 2019.

https://www.diggitmagazine.com/column/why-gramscis-ideas-are-still-relevant.

Beer, Michael. “The Many Faces of Nonviolence – Angela Davis,” Nonviolence International, August 22, 2020. https://www.nonviolenceinternational.net/many_faces_of_nonviolence_angela_davis.

Butler, Judith. The Force of Nonviolence. London and New York: VERSO, 2020.

Caygill, Howard. On Resistance: A Philosophy of Defiance. London and New York: Bloomsbury, 2013.

Chemaly, Soraya. Rage Becomes Her: The Power of Women’s Anger. New York: ATRIA, 2019.

Cone, James H. “Martin and Malcolm on Nonviolence and Violence.” Phylon (1960-) 49, no. 3/4 (2001): 173–83. https://doi.org/10.2307/3132627.

Fanon, Frantz. The Wretched of the Earth. London: Penguin Classics, 2001.

Lischka, Juliane A., and Marcel Garz. “Clickbait News and Algorithmic Curation: A Game Theory Framework of the Relation between Journalism, Users, and Platforms.” New Media & Society, (July 2021). https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211027174.

Lodik, Chanel Matil. Het Antiracisme Handboek. Amsterdam: Bruna Uitgevers, 2021.

Lorde, Audre. Your Silence Will Not Protect You. The UK: Silver Press, 2017.

Maddox, Jessica, and Brian Creech. “Interrogating LeftTube: ContraPoints and the Possibilities of Critical Media Praxis on YouTube.” Television & New Media 22, no. 6 (September 2021): 595–615. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476420953549.

Renninger, Bryce J. “‘Where I Can Be Myself … Where I Can Speak My Mind’ : Networked Counterpublics in a Polymedia Environment.” New Media & Society 17, no. 9 (October 2015): 1513–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814530095.

Russel, Legacy. Glitch Feminism. London and New York: VERSO, 2020.

This essay was based on an assignment that was handed in for the Digital Culture Politics course, which is part of the New Media and Digital Culture MA program at the University of Amsterdam.