I used to be a voyeur. I would spend hours a day reading the comments in endless social media discussions where people were arguing. I would cheer people on who were making sharp analyses, were putting ignorant people in their place and were showing up for others in solidarity. In my head of course. I would be flabbergasted by seeing the thoughtless and hurtful comments others made and would construct elaborate counterarguments. Again, in my head. I would even screenshot comments to send to my friends, explaining to them how I would have responded if I would have decided to bud in. Which, of course, I never actually did. I was a classic lurker.

That changed when the Black Lives Matter movement exploded globally in 2020 and had a political awakening of my privilege within this context. If I was investing so much of my time in reading these comments, why wasn’t I speaking out myself? So I started to engage. I became a true digital gutmensch, trying to explain to strangers on the internet that Christopher Columbus is not a man that deserves celebration (on the contrary) or that gender is not as binary as Western society teaches us. Of course, my attempts failed many times, but at times I got the idea that I did get through to some people.

The Other Cheek

Naturally, I became invested in (one might call it hyperfocused on) the mechanisms behind social media comment discussions, with its countless microaggressions and its counterstrategies that social media users like myself attempt to exacute. In Toward an Ethic of Responsibility in Digital Aggression, Jessica Reyman and Erika Sparby explain that digital aggression in today's digital world is widespread and without clear paths for accountability and resolution. According to their research, much of this activity targets people in subaltern positions that belong to marginalized groups, such as women, people who belong to the LGBTQIA+ community, disabled people, Black1I write Black with a capital letter B, in respect for Black people. See: https://www.oneworld.nl/lezen/discriminatie/sociaal-onrecht/waarom-veel-mensen-zwart-met-een-hoofdletter-schrijven-en-wit-niet/. people, and people of color. They mention that one in four Black people has been the target of harassment, women are twice as likely to be harassed online compared to men, and that religious views are often the basis for aggression. If you ask me, aggression on social media platforms and the polarization between different users is one of the most pressing ethical issues we need to look into within the digital humanities.

James E. Porter, who specializes in digital rhetoric, in his essay Interaction with Friends, Enemies and Strangers, states that, when looking at discussions and online aggression, it is important to look at rhetoric, as “[it] teaches us to be aware of audience, particularly the diversity of audiences. It teaches us that people disagree and have different, conflicting views - often strongly held views. People come from different backgrounds, have different senses of humor, and, of course, subscribe to different ethical systems. Rhetoric makes us aware of context and situation, cultural factors, and power relations. [...] It teaches us that language has the potential to be harmful and hurtful.” In the early web days, many still believed in the utopian ideal of a shared community, according to Porter; “the ideas of shared ethos, civility in discourse, and an open democratic participation all had a chance”. However, on social media platforms “we share a space with many others who don't agree with us, who don’t share the same ethical codes, and who, let’s face it, seem to hate us.” According to Porter, the internet has become a hostile environment where aggression and harassment are issues that must be addressed. And I agree.

In the same line, Judith Butler states that “some people call wounding acts of speech “violence”, whereas others claim that language, cannot properly be called “violent”. Also Teun van Dijk, the father of critical discourse analysis, states that power is not always exercised in obvious abusive acts but may be enacted in the taken-for-granted actions of everyday life. For me, it is clear that online aggression and harassment in social media comments, that microaggressions through language, even when subtle, are a form of violence. More over, according to Porter, verbal attacks in online spaces should not be seen as an individual, but as a historical pattern that goes beyond disagreeing with others; “they are attempts to disenfranchise a person, or an entire people’s right to speak or even exist.”

Porter then raises the question of questions when it comes to ethics; how should we treat each other? According to him, in the line of Greek philosopher Isocrates, “we should greet strangers - or, if not greet, at the very least treat everyone with respect, politeness, civility, and courtesy as human beings - not just for their sake, and not just for our sake, but for all our sake.” Or in other words: treat someone how you would want to be treated. However, what happens when others do not respect you? Should users always turn the other cheek, Porter asks. As most aggression and harassment in the public digital sphere is often directed at marginalized groups, he explains that there are situations where a strong, angry and assertive rhetoric is not even justified, but also necessary. Reyman and Sparby, also state that the advice to “be kind” can mean “do not point out abuse and its effects”. According to them, this call for civility problematically places the blame for aggression on the target instead of the aggressor. They explain that victim blaming can downplay the seriousness of the behaviors that some people experience online. Respect others, but also demand respect, Porter claims, as the answer should never be to ignore aggression; “it has to be named, denounced, and opposed.” According to him, when rhetorics do not work, unrespectful users have to be excluded or users have to exclude themselves.

Of course, currently, much is being said about polarization within the digital domain, where subjects include (technological and human) content moderation, often in the context of ambiguous community guidelines, the safety of users, online threats, and trolling. Naturally, this is important. However, what I am particularly interested in here, are the users who intend to reason with each other. The mechanisms that take place in the space that remains after content moderation; the comments that are deemed appropriate enough by the platform in question to not be removed.

The Comment is the Massage

Luckily, I am not the only person who is fascinated with comment discussions. In his book Reading the Comments, Joseph M. Reagle Jr. explains that “in sifting through the comments, we can learn much more about ourselves and the ways that other people seek to exploit the value of our social selves.” According to him, comments are easily seen, but invisible to the extent that we take them for granted, in the line of Mcluhan’s famous words about fish not being able to see water. Reagle argues that it is important to look at what happens in the margins, to what people encounter in their daily lives. According to him, comments are also pervasive: “Our world is permeated by comment, and we are the source of its judgment and the object of its scrutiny. There is little novelty in the form of the comment itself, but its contemporary ubiquity makes it worthy of careful consideration.” According to him, they are important because they have the potential to affect someone else's status, help make decisions, or alter a person's behavior.

The Digital Public Sphere

When analyzing social media comments it is obviously not possible to not use the concept of ‘the public sphere’, as coined by Jürgen Habermas in 1962. The characteristics of the public sphere, according to Habermas, included: “widespread rational-critical debate, equality, and association, among persons of equal status, freedom from censorship of free expression, and the opportunity to reach consensus about what was partially necessary in the interest of all persons”.

Do these criteria still hold in the digital era of social media platforms and is there such a thing as the digital public sphere?

In Rhetoric Online, Barbara Warnick and David S. Heineman discuss this question. Habermas defined the public sphere as “a space in which people read, discussed, and wrote about opinions, issues, and ideas in coffee houses and public meeting spaces”. Warnick and Heineman add that in our current media environment this might include blogs, social network sites, and mobile communication.

Although it has been argued by many that the Internet is particularly important as an instrument for the emancipation of subordinated social groups and to be more inclusive and suited for marginalized groups to voice their viewpoints in public debate, according to other researchers, such as Thomas Poell and (my Amsterdam University of Applied Science colleague) Tamara Witschge, Habermas’ theory had its shortcomings. Habermas his public sphere excluded many groups of people, such as illiterate people, women, and laborers, for example, Warnick and Heineman explain. In a similar way, this still holds for the public digital sphere. Witschze explains that public debates are not always equally inclusive for participants, as they do not always have an equal status or capacity to influence the debate. It is exactly this power imbalance that I am diving into here.

Poell and Witschge have both researched the public digital sphere in the medium-specific context of forums and blogs in the early and mid-2000s. Poell concludes that, theoretically, forums and blogs can contribute to the public sphere. In the discussions he investigated, the emotional and heated discourse was specifically important because it allowed a variety of groups to articulate their specific identities and discuss social tensions in their own terms. Yet, Poell concludes that in practice, neither the blogs nor forums seem to fulfill their public sphere potential. Also Witschge concludes that “encountering the Other is not sufficient; not only openness to difference is needed, but the discussion also needs openness of the participants towards each other.” According to her, this is not inherent to the technology of the Internet. The question is whether there hope for the social media platforms used in 2022?

Angry by Design

Speaking of what is inherit to the internet. Reyman and Sparby state that “diverse actors, from platform designers and developers to policymakers and legal experts, must become more aware of their own responsibility within particular spaces and moments; the consequences of their decisions, words, and actions”. Something I could not agree more with, as a Communication and Multimedia Design teacher who tries to teach teh next generation of digital designers to be socially aware. Media scholar Luke Munn would agree with me as well. In his essay Angry by Design he researches the design choices of the technical architectures of different social media platforms. Muke explains that the design of platforms shapes our behavior in digital spaces because they are not neutral environments and are designed with particular intentions in mind. Munn adds to what Mel Stanfill and Tarleton Gillespie are famous for illustrating, by stating that platforms are designed to shape participation, where algorithmic sorting privileges some content over other types of content by what is permitted and how objectionable behavior is policed. Munn states that other scholars have already proved that social media enables negative messages to be distributed farther. Nothing new here so far.

His work becomes particularly interesting when he focusses on anger specifically. Munn his research shows how Facebook’s architecture, for example, induces user experiences that are stressful and impulsive, establishing some of the key conditions necessary for angry communication. He states that in Facebook’s design, posts with higher engagement scores are included and prioritized; posts with lower scores are buried or excluded altogether. Because of this, polarizing posts, often with a strong moral charge and controversial topics, that provoke a reaction and establish opposed camps, consistently achieve high engagement. Material that evokes emotions, that evokes anger.

So users are being nudged to become angry by the default of social media platforms’ architecture. This anger, however, does not only have a design origin. It is equally important to look at anger as a broader sociological, even philosophical phenomenom. When discussions take place between humans with alternative positions, these discussions often result in antagonistic situations, with ‘us/them’ or ‘friend/enemy’ dynamics, where those who are perceived as different start to be perceived as putting into question identities and threaten the existence of others, as Chantal Mouffe explains. In this context, not every user who engages in comment discussions has an equal position. When marginalized people enter debates where, at times, they have to defend their own human rights, which can be extremely triggering, for them (us), this is not only a political experience, but also a personal one (although the personal is always political, but I digress), that naturally triggers emotions such as anger.

But, could anger be a good thing?

(Spoiler: the answer is yes.)

Soraya Chemaly, in Rage Becomes Her, explains that the context of anger often governs how it can be expressed - especially for [marginalized groups], one of the foremost regulators of their expression is how they are supposed to behave in public, where they are often tone policed, [gaslit and confronted with fragile behaviour of privileged people], keeping them from being engaged in politics. Showing anger, becomes an act of resitsence then. Or as Porter would say; showing anger is an act of naming, denouncing and opposing aggression.

So. What tactics are marginalized people using exactly, when confronted with microaggressions? Do the Habermasian criteria still hold in the digital era of the platform society? Is there currently such a thing as the digital public sphere? And what does it mean for that sphere if its environment is designed to make us angry?

Warning: I am not neutral

Before I continue I feel the need to reflect on my personal intentions and situated knowledge, as I actively chose not to be neutral in these matters. As a white, educated, queer, neurodivergent, ambiamorous, Dutch demiwoman with a successful career and an invisible chronic condition, who has an intersex transgender father, lableless mother, and bigender partner, I try to be aware of the privileges I do and do not have and act ethically and accordingly. I am making a conscious choice of taking a clear political stance against oppression by looking at this from the point of view of those who are marginalized. As a researcher, it is important to not be neutral when it comes to human rights and we should not be pretending that objectivity is achievable in the first place. As Donna Haraway states; rational knowledge should not pretend to be free from interpretation, from being represented, self-contained, or fully formalizable - it is an ongoing process of critical interpretation, and the only way to find a larger vision is to be somewhere in particular. I am aware of the fact that I cannot be free of my own interpretation, nor do I try to be free of it. Injustice makes me angry and I think that is a suitable response.

I would also like to add that I intend to always have an intersectional lens; a lens that pushes against single-axis frameworks for analyzing power and instead advocates for more expansive frameworks that highlight the full complexity of interlocking systems of oppression, as Grenshaw explained this concept. Whereas some will definitely find the the thinkers that inspire me to be too antagonistic or radical in thought, it is exactly these qualities that I appreciate the most. Not only do they provide important complementary nuances that most literature about digital culture could not provide by itself, they are thinkers that do not turn the other cheek.

Diving into Political Comments Discussions

When putting all of this to the test in the real world, what better place to look than the political disussions that emerge at newspapers sharing articles that concern identity politics on their public Facebook pages.

Facebook, the social media giant with its billions of monthly active users, global reach, link to online harassment, and political and ideological influence (as Tania Bucher coins the platform in her book about Facebook politics), is the perfect platform to research the more nuanced forms of discussions. Bucher states that Facebook is by no means a neutral platform as “the very design of Facebook discriminates against certain actors while privileging others. On Facebook, design, and engineering intersect with the possibilities for free and equal expression, information access, and news consumption”, which includes the potential for dangerous speech. Even Zucke himself, in reaction to this, has attempted to drastically change Facebook’s branding from a public ‘town square’ to an encrypted communication platform that feels like a safe ‘living room’, Bucher explains.

Looking at news papers specifically makes sense, as Facebook has drastically changed the news industry, as José van Dijk, Thomas Poell and Martijn de Waal explain in their book The Platform Society. They explain that the increase in social media use, because of the rise of mobile applications, has ensured that Facebook is progressively dominating the distribution and selection of news, as news organizations hand over their content to the platform. According to them, because of the datafication of news, caused by platforms such as Facebook, it has become essential for news organizations to trace how each piece of separate content circulates online. In this context, Van Dijk, Poell and de Waal state that this affects the curation of news, as it becomes more important what types of content generate traffic and virality. According to them, the Facebook architecture, as Munn also explains, prompts users to share content with their friends and followers, soliciting an emotional response.

In the Netherlands, the three biggest newspapers where users from different political backgrounds and marginalized and non-marginalized positions are most likely to meet each other in the comment section are De Volkrant (249.000 Facebook followers), NRC (202.583 Facebook followers), and Parool (121.508 Facebook followers).2Looking at newspapers such as Telegraaf (587.731 Facebook followers) would be less relevant for this particular research, as it is a distinctly right-wing newspaper where its followers will most like not encounter users from marginalized groups. When looking at smaller independent newspapers, such as OneWorld, with a more progressive and leftist ideology, the same issue would arrive.

To select comments for these three newspapers, I selected the top three most commented-on posts from 2020 that discuss identity politics topics using the Digital Methods tool CrowdTangle3I randomly selected 20 comments by marginalized users per post as a sample, analyzing 60 comments per newspaper and 180 comments in total (from the period 01-01-2020 - 31-12-2020). I manually filtered out comments by non-marginalized users and neutral comments as noise. I also documented the number of likes and replies a comment got per comment. I also filtered out noise, such as posts with a large number of comments but that were not political in natur, manually.. 2020 was was the year when people their time spent online increased significantly because of the outbreak of the covid pandemic and its corresponding lockdowns. 2020 was also the year of the Black Lives Matter protests that sparked identity politics discussions around the globe.

The Netherlands is a Racist Country

Naive and privileged that I am, I expected the Facebook posts to include diverse topics within the range of identity politics, such as transgender healthcare, abortion rights and gender equality. However, all subjects only concerned racism, xenophobia and nationalism, one way or another. This should not have come as a surprise, as the Netherlands has a dark history of colonialism and slavery, and is predominantly a right-wing country where, unfortunately, racism is a huge problem. Subjects concerning racism and much-needed anti-racism are known to frequently cause debate and controversy here.

Fig. 1: Facebook post from Het Parool with 2.9K comments about only a small minority being pro-Zwarte Piet. Zwarte Piet is a traditional Dutch holiday with harmful racist caricatures that has caused a lot of controversy over the past years in the Netherlands. During this holiday an elderly white man on a horse has Black ‘helpers’ who pass out presents and candy to kids. Many people, who often share a progressive idealogy, are in favor of adjusting Zwarte Piet to a less hurtful figure that does not have a clear connotation with the Netherland’s history in slavery, while often conservatives are against this.

Fig. 2: Facebook post from Het Parool with 1.7K comments about how Dutch artist Akwasi does not feel safe in his own house anymore because his address was shared publicly after being openly anti-racist.

Fig. 3: Facebook post from Het Parool with 688 comments about Sylvana Simons, the first-ever Black political party leader in Dutch history, (supposedly) having a confrontation in a school class of teenagers.

Fig. 4: Facebook post from de Volkskrant with 1.6k comments about Dutch rapper Jay-Way making a comparison between slavery and Zwarte Piet in the Netherlands.

Fig. 5: Facebook post from de Volkskrant with 1.1k comments about the horrible conditions of the refugee camp in Moria.

Fig. 6: Facebook post from de Volkskrant with 875 comments about Dutch talk show host Johan Derksen, a white man, making racist comments about Akwasi and Zwarte Piet on his show and him acting defensive when being called out on it.

Fig. 7: Facebook post from NRC with 905 comments about France (supposedly) not wanting a French Islam community.

Fig. 8: Facebook post from NRC with 791 comments about the state of the Islam community in the Netherlands.

Fig. 9: Facebook post from NRC With 746 comments about Dutch activist Naomie Pieter supposedly not being ‘Black enough’ for the Black community because she is queer.

Racism-related issues and identity politics are sensitive issues in The Netherlands that are known to frequently cause debates, so newspapers playing into that with their news curation and presentation, wuth Facebook’s algorithms in mind, makes sense if they are aiming for maximizing user engagement and revenue. The fact that, for example, Het Parool, in their Facebook post, shares that Sylvana Simons, who has previously caused multiple media controversies in the Netherlands already, clashes with a group of teenagers and that instead of her teaching them a lesson they taught her a lesson, (Fig. 3), while the article itself explains that the situation was more nuanced, illustrates this. In reality, during the class Simons taught, she was self-reflective and ended up bonding with her students.

Polite or Angry?

To analyze the comments I turn to Teun van Dijk his critical discourse analysis method; “a type of discourse analytical research that primarily studies the way social power abuse, dominance and inequality are enacted, reproduced and resisted by text and talk in the social and political context.” Critical discourse analysts, like myself, “take explicit positions, and thus want to understand, expose and ultimately resist social inequality”. Van Dijk explains that power structures can be implicit. My aim is to make the unexplicit societal power relations that are represented in these comments explicit.

It became clear to me that two types of tactics were used frequently by marginalized users and their allies; staying polite or being angry. The polite commenters stay friendly, understanding try to evoke empathy, and/or use facts to support their claims. The angry commenters use passive aggressiveness, and/or display anger and/or sadness. Angry commenters also use facts to support their claims. Let me introduce these tactics, in the spirit of figure design, by illustrating different types of comment personas.

“Is Your Keyboard Broken or Something?”

For the following examples, a trigger warning is in place, as some of the comments contain problematic and hurtful views in terms of racism, xenophobia and nationalist sentiments.4Please note that the grammatical errors within the English translations are intentional, as I have tried to stay as close to the original Dutch grammar (which was often flawed) as possible.

The polite commenter: friendly

The friendly commenter has a kind tone of voice. The friendly commenter does not show their possible annoyance or anger while making their point. Friendly comments are often elaborate, such as the ones in Fig. 10. Other types of friendly comments are shorter and are meant to encourage other commenters, with phrases such as ‘You go girl! You’re completely right.’

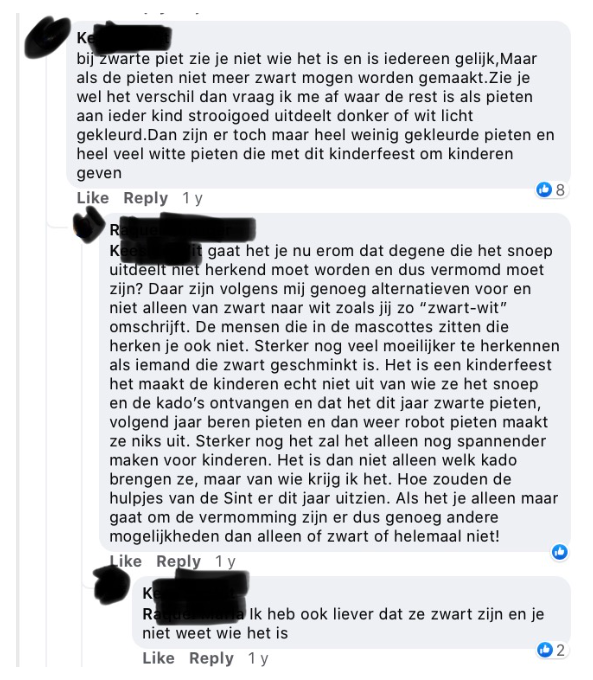

Fig. 10: Translation: K.: ’with zwarte piet you don't know who it is. But when petes are not allowed to be black. Can you see the difference then, when the petes give the candy to kids when they are white or lightly colored. Then there are very few colored peets and a lot of white petes that say they care about kids.’ R.: ‘Is it about whether the person handing out the candy should not be recognized thus should be disguised? I think there are a lot of alternatives for that that are not as black and white as you describe. The people in those mascottes you don't recognize either. It is harder to recognize when someone is painted black. It is a holiday for kids and kids don't care if they get candy or presents from zwarte pieten this year, bear pieten next year and robot pieten the year after. In fact, this would only make it more exciting for them, It’s going to be exciting for them to know what present they get, but also who will bring it to them. What would Sinterklaas his helpers look like this year? If your point is only about being disguised, there are a lot more possibilities than black or not black!’ K.: ‘I would still want them to be black.’

In this example, R. tries to solve one of K. his concerns about the new look of Zwarte piet, by explaining in a very friendly and elaborate way, why, luckily, there are a lot of other exciting ways to make piet anonymous, and that kids can still happily engage in the same holiday without hurting others. R. her tactic was unsuccessful, as K. replies that he still wants Zwarte Piet to remain Black, without engaging in any of the points she has made.

The polite commenter: understanding

The understanding commenters try to show their opponents that they understand where they are coming from before making their point, in an attempt to make them listen to them.

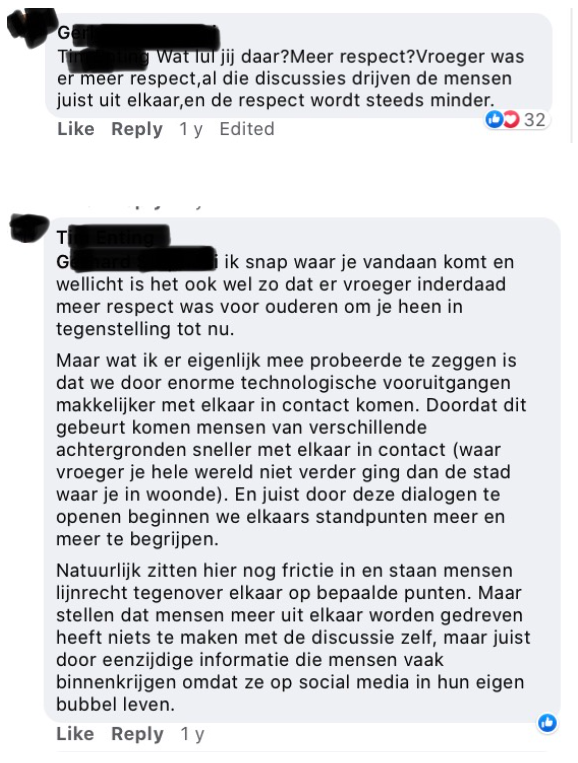

Fig. 11: Translation: G.: ‘What the hell are you talking about? More respect? There used to be more respect back in the days, all these discussions cause people to drift apart. There is less and less respect’ T.: ‘I understand where you're coming from and perhaps it is the case that indeed, there was more respect for older people around you, compared to the current day. What I am actually trying to say is that because of technological improvements it is easier to be in contact with each other. Because this happens people with different backgrounds come into contact with each other faster (where in the past your world was not bigger than the town you lived in). And because of the opening of these dialogues we can try to understand each other's viewpoints more and more. Of course there will be some friction and some people have opposite views. But to say that people are being divided has nothing to do with the discussions itself, but with the one-sided information people often consume because they live in their own bubble on social media.’

When G. rudely says that everything used to be better in the past (a classic conservative catchphrase) and that people do not have respect for others anymore, T. starts off by saying that he understands where G. is coming from and that he might be right, before continuing his argumentation in which he stays polite throughout the entire comment.

The polite commenter: empathy

The commenter who tries to evoke empathy in their opponents tries to make them see the emotional effect the argument has on them and/or tries to show the human side of their own argument, by either sharing a personal experience or asking them to understand how a certain situation must feel for someone else.

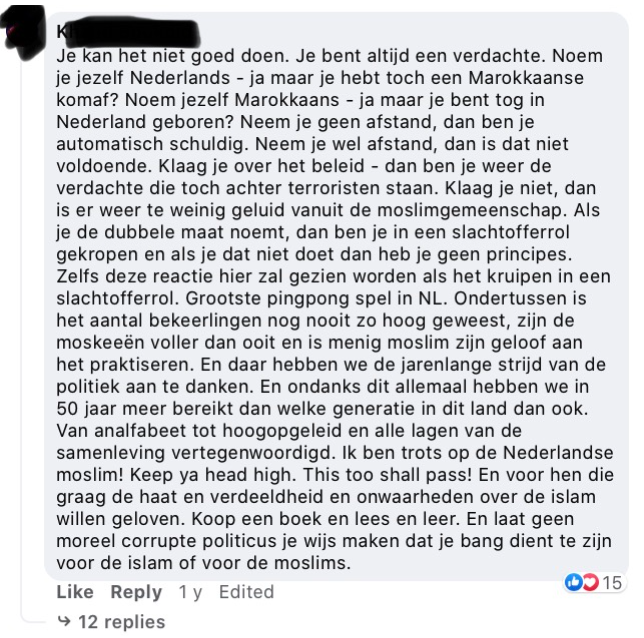

Fig. 12: Translation: K.: ‘You can’t ever do it right. You are always a suspect. Call yourself Dutch - but you have Moroccan roots? Call yourself Moroccan - but you were born in the Netherlands? Don’t take your distance, then you are automatically guilty. Do take distance, then it’s not enough. Complain about policy - then you're a suspect who stands with terrorists. Don’t you complain, then there is not enough input from the Muslim community. If you call out the double standard, then you play the role of the victim and if you don’t you don’t have any principles. Even this comment will be seen as playing the victim. It’s the biggest ping-pong match in the Netherlands. Meanwhile the number of converts has never been this high, the mosques are fuller than ever, and a lot of muslims are practicing their faith. And we got the years-long political battle to thank for that. And despite all of this we have achieved more than any generation before in this country the past 50 years. From illiterate to highly educated, all the classes of society are represented. I am proud of the Dutch Muslim! Keep ya head high. This too shall pass! And for those who like to believe the hate, and division and untruths about the islam. Buy a book and read and learn. Don’t let a corrupt politician make you believe you have to be afraid of the islam or muslims.’

K. shares his personal experiences of what it is like being a Muslim person in the Netherlands. All these impossible contradictory standards to uphold are part of his daily life and the daily lives of many other Muslims. By making that concrete for other commenters, he tries to evoke empathy, using his own experiences.

The polite commenter: facts

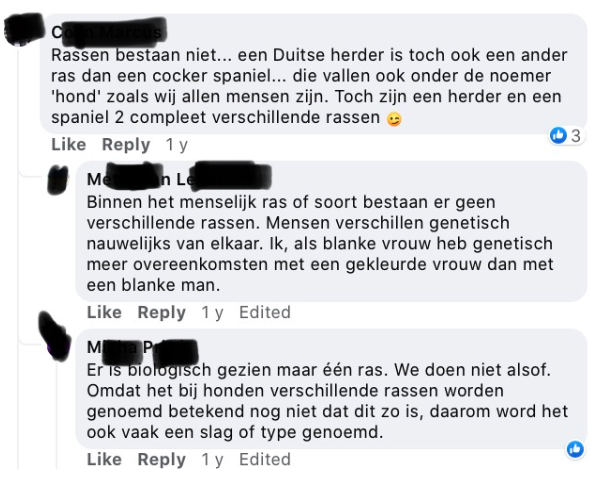

The polite commenter who uses facts tries to persuade their opponents with factual information about the subject matter, focussing on rational logic instead of emotion, occasionally adding sources, while remaining polite.

Fig. 13: Translation: C.: ‘Races don’t exist… A German shepherd is a different race than a cocker spaniel right? They are both dogs, just like we are humans, but still shepherds and spaniels are two different races.’ M. L.: ‘Within the human race there are no different races. People hardly differ genetically speaking. I, as a white woman, have more in common with a woman of color, than with a white man, genetically speaking.’ M. P.: ‘Biologically speaking there is only one race. We are not pretending. Because they call it different races with dogs, it doesn't mean that this is really the case. That is why they often call is a type of dog.’

When C. compares humans to dogs, including a passive-aggressive wink emoji, to make a point about supposedly racial differences between Black and white people, both M. L. and M. P. explain to him that, in fact, there is no such thing as different human races, using facts about biology and genetics, without losing their temper; they focus on presenting C. with accurate information.

The angry commenter: passive-aggressiveness

The passive-aggressive commenter doesn’t comment on the content of the opponent's argument. Instead, they use sarcastic comments and light threats to show the absurdity of their opponent’s arguments.

Fig. 14: Translation: R.: ‘GO BACK TO YOUR OWN COUNTRY, AND HELP THERE, AND MAKE SURE THAT THE MINISTERS CAN’T ARRIVE THERE, THAT IS THE BIGGEST PROBLEM’ L.: ‘Hey Rita, is your keyboard broken or something?’

When R. states the most classic sentiment a commenter could state in terms of xenophobia, ‘go back to your own country’ in all caps, L. does not bother to give a content-based argument in an attempt to show why Rita her comment is problematic. Instead, she makes a completely unrelated passive-aggressive remark about R. her keyboard, trying to make her aware of how intense her comment looks in all caps, pointing out the absurdity of the comment.

The angry commenter: offense

The offended commenter is clearly angry, hurt and/or outraged. They indicate their frustration by being distinctly emotional, often using swear words.

Fig. 15: Translation: J.: ‘If they are white those Black Lives Matter idiots are going to yell and say they are being excluded, so that’s racism.’ E.: ‘Could be.’ H.: ‘What idiots are you talking about? Because you are the biggest idiot here. You are typing a lot of crap. You should educate yourself in history.’

When J. calls Black Lives Matters protestors idiots and ridicules the experience of racism, H. reacts in an emotional way and calls J. an idiot in return. She does not give a content-based argument about why his comment is problematic, she just calls him out on the fact that his comment is ‘crap’ and suggests him to start to educate himself, without having to engage in the emotional labor of educating him herself.

The angry commenter: sadness

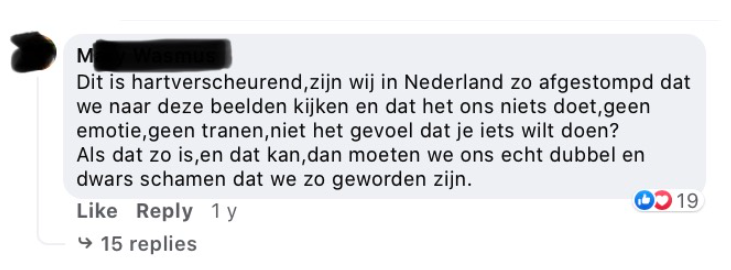

The angry sad commenter is hurt and shows that the opponent's comments make them sad.

Fig. 16: Translation: M.: ‘This is heartbreaking. Are we this numb in the Netherlands? Can we look at these images without caring, no emotion, no tears, not giving you the feeling you want to do something? If that is the case, and it can be, we should be ashamed of ourselves for becoming like this.’

When commenting on an image of refugees sleeping outside in the cold, M. states that this breaks her heart. She expresses clearly that the fact that these images of people living in horrible conditions, without the Netherlands helping them to improve those, do not make people in the Netherlands cry or the urge to act, makes her deeply sad and ashamed. I feel her.

The angry commenter: facts

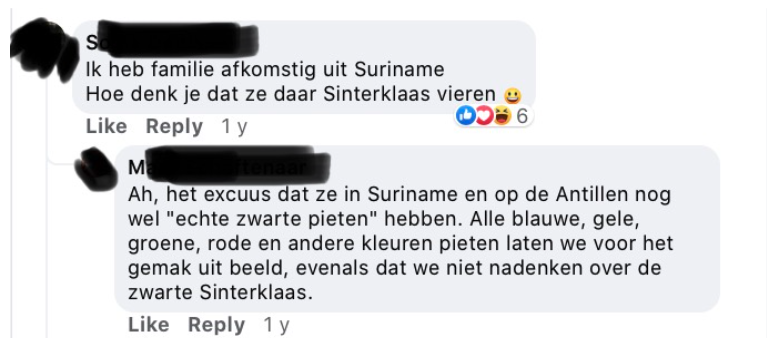

The angry commenter who uses facts tries to persuade their opponents with factual information about the subject matter, focussing on rational logic, occasionally adding sources, while at the same time clearly showing their frustration and emotions.

Fig. 17: Translation: S.: ‘I have family from Suriname. How do you think they celebrate Sinterklaas there?’ M.: ‘Ah, the excuse that they still have ‘real Zwarte Pieten’ in Suriname and the Antilles. All blue, yellow, green, red, and other colored Pieten we’ll just leave out of the picture for convenience, just as thinking about the black Sinterklaar.’

When M. explains to S. that there are a lot of rainbow-colored Pieten in Suriname and even Sinterklaas is Black there, making her argument about the fact that supposedly in Suriname people still celebrate Sinterklaas with Zwarte Pieten and that is why it should be fine in the Netherlands as well ‘because everyone is Suriname is Black and they don’t even mind so why should we?’, he shares facts with her to debunk this argument, while also clearly having a passive-aggressive tone.

When looking at the Habermasian criteria for the public sphere (rational-critical debate, equality and association, among persons of equal status, freedom from censorship of free expression, and the opportunity to reach consensus about what was partially necessary for the interest of all persons), most of these criteria are obviously not represented in these comments. Users that use facts in their arguments do try and engage in rational debate, however, most of the comments are not rational but emotional and do not engage with the subject matter. Users who try to be understanding towards other commenters, as a form of what Mouffe would call agnostic debate, in an attempt to create an equal position in the debate, are severely underrepresented and most of the time their attempts fail.

Dominant Tactics

When looking at numbers for a second5I categorized all selected comments according to the polite/angry labels and their sub-labels. The sub-labels were able to overlap., what is striking, is that the comments I analyzed (of which the above are just examples to illustrate them) are predominantly angry. Angry comments also receive a bit more engagement through likes and replies, compared to polite comments. I had expected that the dominant tactic would be politeness. Honestly, I was pleasantly surprised that marginalized people are not playing nice. In this sense, Facebook does indeed favor anger, as it causes more engagement, as opposed to politeness.

The Polite Commenter

When engaging in debate, polite commenters are in line with the previously mentioned Greek philosopher Isocrates, who believed we should treat everyone with respect, politeness, civility, and courtesy as human beings. Without getting into the complexity and long histories of these debates, in essence, polite commenters have similar strategies as those who identify with the core values of the nonviolence beliefs. One of the most well-known persons to advocate for nonviolence was, of course, Gandhi. He said that “we may never be strong enough to be entirely nonviolent in thought, word, and deed. But we must keep nonviolence as our goal.” Of course, another influential figure in favor of nonviolence was Martin Luther King. He saw nonviolence as the most suitable tactic for Black people in the U.S. Civil Rights Movement, as James H. Cone writes. Cone explains that King identified love as the most powerful force in society, and he saw nonviolence as a political expression of love. In the line of King, when marginalized users engage in Facebook comment discussions with non-marginalized users who express oppressive views, they attempt to love their enemies and are trying to make them their friends, instead of trying to destroy them.

The Angry Commenter

In turn, angry commenters seem to have similar intentions as those who see violence as a positive, productive political force. As James Cone explains, one of the people who directly criticized King’s nonviolence ideology was Malcolm X. According to him, self-defense is an essential element of what it means to be human, Cone illustrates. Malcolm X thought that Black people should use any means necessary to gain their freedom. Franz Fanon, who wrote about violence in the context of decolonization, is also a classic revolutionary. For him, “decolonization is the meeting of two forces, opposed to each other by their very nature [...] marked by violence.” According to Fanon, nonviolence ensures that oppressors remain in power. for Fanon, violence is a unifying force, and that “at the level of individuals, violence is a cleansing force. It frees the native from his inferiority complex and from his despair and inaction; it makes him fearless and restores his self-respect.” For angry commenters, it could feel productive and freeing to become angry and demand respect then.

Another important take on (non)violence to mention here is the one from Angela Davis. She states that the only reason for the fact that there are violent revolutions is that our society, which is determined by those in power, is violent itself. In a similar way, Facebook is designed in a way where the environment stimulates violent communication.

Chemaly, in line with Fanon, claims that anger should be liberated, as “the root of the word aggressive is related closely to the Larin word 'aggredi', meaning ‘to go forward’”. According to Chemaly, anger infuriates those in power, as it indicates marginalized people not conforming to traditional norms. Audre Lorde also states, in line with Davis, that “it is essentially not the anger that lies between [people], but rather the virulent hatred leveled against all women, people of colors, lesbians and gay men, poor people, [trans people], [disabled people], against all of us who are seeking to examine the particulars of our lives as we resist our oppressions”. Simply by speaking in anger, marginalized groups violate powerful rules because, according to Chemaly, as their anger is a strong reminder of social imbalances. Anger is a moral emotion that makes it possible for people to make judgments, and [marginalized people] are supposed to be removed from the authority that comes with that, which is precisely why [marginalized people] should not only have the right to claim anger, it is their moral obligation to do so. When denying anger, [marginalized people] deny their right to use it effectively and appropriately. Chemaly explains. According to her, anger can help locate communities and to organize for collective social action, as it is a source of energy, joy, humor and resistance.

Anger as Glitch

How, then, would this translate to the digital realm? The answer could be found in Legacy Russel’s Glitch Feminism. She states that violence is a key component of the patriarchy [and other oppressive systems] and that glitch feminism is about wanting a better world and could be seen as a rejection of the here and now. Russel states that even though “'the paradox of using platforms that grossly co-opt, sensationalize, and capitalize on POC, female-identifying, and queer bodies (and our pain) as a means of advancing urgent political or cultural dialogue about our struggle is one that remains impossible to ignore.” Russel explains that “what these institutions—both online and off—require is not dismantling but rather mutiny in the form of strategic occupation”:

“Glitch is [...] an active word, one that implies movement and change from the outset; this movement triggers error. [...] Traversing through these origins, we can also arrive at an understanding of glitch as a mode of nonperformance: the “failure to perform,” an outright refusal, a “nope” in its own right, expertly executed by machine.[...] glitch moves, but glitch also blocks. It incites movement while simultaneously creating an obstacle. Glitch prompts and glitch prevents. With this, glitch becomes a catalyst, opening up new pathways, allowing us to seize on new directions. [...] It helps us to celebrate failure as a generative force, a new way to take on the world.”

Consequently, the angry commenter uses their anger in Facebook comment discussions as a type of a glitch; as a form of resistance to those who share oppressive discourses that affect them.

Challenging Norms

These individual comments represent a broader phenomenon, of course, where marginalized people are attempting to challenge norms that are oppressive to them. Comment discussions are part of a culture war that is currently happening.

Jan Blommaert explains how Gramsci his theory about this, which was presented in the Prison Notebooks published in the 1950s, is still essential in the digital era. Blommaert briefly explains the foundations of Gramsci’s theory; what enables the bourgeoisie to remain in power is not just its control over the economic infrastructure and the state - it was its control over the hearts and minds of the people, including those belonging to the working class. According to Gramsci, bourgeois ideals have become normal to most people and have become unquestionable as sociopolitical values. Gramsci called this ‘soft’ power, in opposition to ‘hard’ power which refers to material economic conditions and the state. Gramsci called this type of soft power hegemony, and according to him, this is crucial when it comes to revolutionary strategy. To be successful, a strategy should be aimed at the hard power, to capture the government, army, and police, and should be direct and violent if needed, but it should also be aimed at the soft power; the hegemony. According to him, revolutionaries should gradually change the dominant culture of the people and replace the dominant ideas, ideals and assumptions with different ones. This is a slow, indirect, passive and patient process and the influence of education, the arts and media are necessary for the execution. According to Gramsci, only when this hegemony is achieved, the direct and violent part of the strategy can be successfully executed.

“Revolution, according to Gramsci, demanded intellectual control of the public sphere, and class struggle was not just an economic affair but a cultural one as well.” The social media comment could be seen as a tool, or perhaps the term weapon is better suited, for this battle of ideas. Blommaert states that it is only logical that Gramsci’s theory takes us online; “little can be done these days in the way of political analysis without a careful look at how [they are] articulated in endless online debates”. Blommaert states that culture wars proceed through a wide variety of old and new semiotic technologies, including memes, trolling, irony, and algorithmic activism, exploiting the full range of affordances offered by the online infrastructure in attempts to change the major direction of public opinion.

As language, especially in the context of microaggressions, comments are a form of violence, non-violence or counter-violence then. Let’s make a link to Michel Foucault here, who explains in The Order of Things that human language is a demonstration of the human mind which slowly changes through time and through cultural exchange, just like the cycle of human beliefs. The language the users who engage in these discussions use is part of a cultural negotiation for public opinion. Words then, are never just words; they also constitute actions, as Porter claims as well.

Empathic by Design?

Comment discussions, in line with the conclusions that Poell and Witschge made years ago, do not meet the criteria for a Habermasian public sphere. A crucial criterion for the public sphere is that its participants must have an equal position. Habermas did not acknowledge the hegemonic nature of the ineradicability of antagonism within the public sphere, and in the public digital sphere, marginalized users do not have an equal position compared to non-marginalized users either. The fact that empathy seems to be favored within this environment shows that Facebook comment discussions do have the potential to be a public digital sphere on some level. However, this potential is currently not met.

When Davis called for a paradigm shift, where we challenge our pre-existing biases, toward a world free of violence; that is, a world free without racism, white supremacy, queerphobia, and all other systems of oppression, she probably did not have digital design in mind. However, the fact that empathy had the potential to be a successful tactic to challenge oppressive norms, does make me wonder. What if critical designers changed the infrastructures of current social media platforms to ones where empathy is encouraged? Or even better, what if we collectively designed alternative platforms based on anti-capitalist, anti-white-supremacist and anti-patriarchal values such as solidarity, care, compassion, hope and even love? What if we use speculative design techniques to imagine an alternative society where we don’t need anger as fuel and ammunition for resistance anymore? What if we move from ‘anger by design’ toward ‘empathy by design’?

—

This Longform is based on the MA thesis I wrote for the New Media & Digital Culture program at the University of Amsterdam in 2022. The original text is three times as long as this Longform and includes the following:

- An in-depth discussion of methodological choices and theoretical concepts

- Pie charts and graphs that visualize the complete dataset of the comments that I analyzed

- More on the interface and affordances of Facebook comments

- Interviews with users who read comment discussions but decide not to engage in them (lurkers)

Please contact me at chloe [at] networkcultures [dot] org if you wish to read it.

I would like to thank the Institute of Network Cultures and the Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences for supporting me in obtaining my MA degree in addition to my employment, Marc Tuters who was my supervisor, Geert Lovink for his endless support and trust, my colleagues Sepp, Tommaso & Laurence, and Sanne, Nicky, Tanya & Vin for their unconditional love and support.

—

Works Cited

Biography.com. “Gandhi Quotes.” Accessed December 22, 2021. https://www.biography.com/news/gandhi-quotes.

Blommaert, Jan, “Why Gramco’s Ideas are Still Relevant,” Digit Magazine, November 11, 2019.

https://www.diggitmagazine.com/column/why-gramscis-ideas-are-still-relevant.

Beer, Michael. “The Many Faces of Nonviolence - Angela Davis,” Nonviolence International, August 22, 2020. https://www.nonviolenceinternational.net/many_faces_of_nonviolence_angela_davis.

Bucher, Taina. Facebook. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2021. Kobo.

Butler, Judith. The Force of Nonviolence. London and New York: VERSO, 2020.

Chemaly, Soraya. Rage Becomes Her: The Power of Women’s Anger. New York: ATRIA, 2019.

Cone, James H. “Martin and Malcolm on Nonviolence and Violence.” Phylon (1960-) 49, no. 3/4 (2001): 173–83. https://doi.org/10.2307/3132627.

van Dijk, José, Thomas Poell, and Martijn de waal. The Platform Society: Pulic Values in a Connective World. New Tork: Oxford University Press, 2018.

van Dijk, Teun. Discourse and Power. London: Palgrave: 2008.

Fanon, Frantz. The Wretched of the Earth. London: Penguin Classics, 2001.

Foucault, Michel. The Order of Things. London and New York: Routledge Classics, 2002.

Gillespie, Tarleton. Custodians of the Internet : Platforms, Content Moderation, and the Hidden Decisions That Shape Social Media. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2018.

Haraway, Donna. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies14, no. 3 (1988): 575–99. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066.

Lorde, Audre. Your Silence Will Not Protect You. The UK: Silver Press, 2017.

Mouffe, Chantal. Agonistic: Thinking the World Politically. London and New York: VERSO 2013. ePub.

Munn, Luke. “Angry by design: toxic communication and technical architectures.” Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 7, no. 53 (2020): 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00550-7.

Nduwanje, Olave. “Waarom veel mensen Zwart met een hoofdletter schrijven.” OneWorld, December 7, 2021. https://www.oneworld.nl/lezen/discriminatie/sociaal-onrecht/waarom-veel-mensen-zwart-met-een-hoofdletter-schrijven-en-wit-niet/.

Poell, Thomas. “Conceptualizing forums and blogs as public sphere.” Digital material: tracing new media in everyday life and technology, Amsterdam University Press. (2009): 293-251. http://www.let.uu.nl/tftv/nieuwemedia/images/uploads/Digital-Material.pdf.

Porter, James E. “Interacting with Friends, Enemies, and Strangers.” In Digital Etics: Rhetoric and Responsibility in Online Agression, edited by Jessica Reyman and Erika M. Sparby, xvi - xxii. New York and London: Routledge, 2020.

Reagle Jr., Joseph M. Reading the Comments: Likers, Haters and Manipulators at the Bottom of the Web. London: MIT Press, 2016.

Reyman, Jessica and Erika M. Sparby. “Toward an Ethic of Responsibility in Digital Agression.” In Digital Etics: Rhetoric and Responsibility in Online Agression, edited by Jessica Reyman and Erika M. Sparby, xvi - xxii. New York and London: Routledge, 2020.

Rogers, Richard. Doing Digital Methods. London: SAGE Publications Ltd, 2019.

Russel, Legacy. Glitch Feminism. London and New York: VERSO, 2020.

Stanfill, Mel. 2015. The Interface as Discourse: the Production of Norms Through Web Design. New Media & Society 17(7): 1059-1074.

Warnick, Barbara and David s. Heinman. Rhetoric Online: The Politics of New Media. New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 2012.

Witschge, Tamara. “(In)difference Online.” PhD diss, University of Amsterdam, 2007.