Photo: Nadine Roestenburg

[Video + transcript of the talk I gave at the ‘Artistic Interventions in Finance’ panel during MoneyLab: Economies of Dissent on the 3rd of December 2015. Videos of the other panelists (Stephanie Rothenburg, Nuria Guell & Levi Orta, Scott Kildall, DullTech™, Raluca Croitoru) can be found here.]

The Competitive Aesthetics of Failure

Hello everyone. First of all, I’d like to thank the Institute of Network Cultures for organizing this event and inviting me. I’m glad to be here.

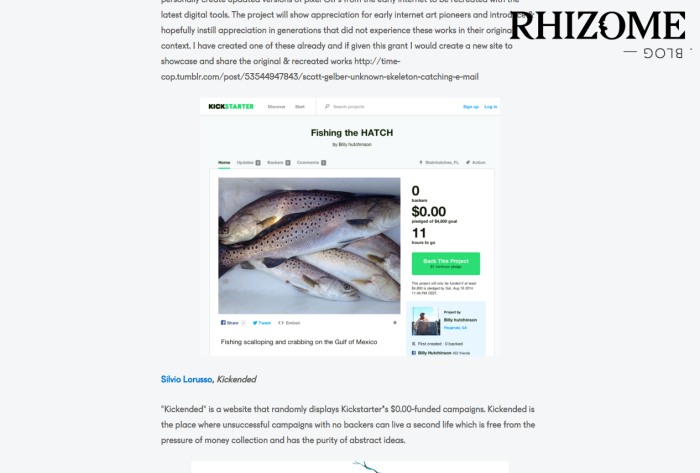

Today, I’m gonna talk about a project called Kickended and the path that my research took from there. Made in 2014, Kickended is a Kickstarter clone that only includes campaigns nobody wanted to pledge for. Campaigns that raised exactly zero dollars.

So sad. http://t.co/WX6bf9PFO0. Kickstarter projects that couldn't even get their mom to kick in $10.

— Darcy Casselman (@flying_squirrel) November 12, 2014

But before going into those, I’d like to explain how and why I decided to build this archive. The idea came when I started noticing how often people in my extended network were using crowdfunding in order to sustain their artistic or curatorial practice.

Suddenly, it seemed that any show needed some financial support from peers. Any semblance of a project became suitable to a campaign. Despite frequently appearing in my feed, these mostly ineffective campaigns were invisible. No trace of them could be found in the news, filled instead with blatantly successful ones.

On blogs like FastCompany or TechCrunch you would find a plethora of videos characterized by a standardized aesthetics made of emotional storytelling, cheerful banjo melodies, slick shots, and motivational calls to action.

Kickended itself is the result of a failure — if you want to call it like that — since I originally submitted the idea to Rhizome’s Net Art Microgrants competition. Kickended made it to the final round but, unfortunately, it didn’t go through.

I appreciated the irony of this meta-failure and decided to do it anyway. I wanted to expose the ‘dark side’ of crowdfunding and see how people would react to it. There was one problem: Kickstarter doesn’t allow for searching projects by the amount of money raised.

The TL;DR reason why this image means ‘survivorship bias’.

Kickstarter’s interface incorporates the same kind of survivorship bias I’ve found in the news, since it focuses on campaigns that ‘survive’ the funding process, and indirectly overlooks the ones that don’t.

After some research, I stumbled on Kickspy, a service that offered a detailed search engine to look into Kickstarter’s projects, so I could automatically clone the ones I wanted. Sadly, Kickspy was shut down some time ago.

I deliberately chose to use a neutral, even positive tone in the website. The word ‘failure’ doesn’t appear anywhere in it. Once Kickended was ready, I found a great diversity of projects characterized, as you can imagine, by a far richer aesthetics.

I discovered lots of cartoons and comics, like this one, that happens to be my favorite.

I caught some awkward moments in the intimate spaces of many campaigners.

I realized that many people kickstart music, often Christian.

Of course, proposals of online apps and services don’t lack. However, it seems that programmers do.

Likewise, there’s an abundance of horror and sci-fi movies.

And there is plenty of ‘potato salad’ spinoffs.

Until crowdfunding recursively addresses itself, with this campaign to fund a conference about getting funded.

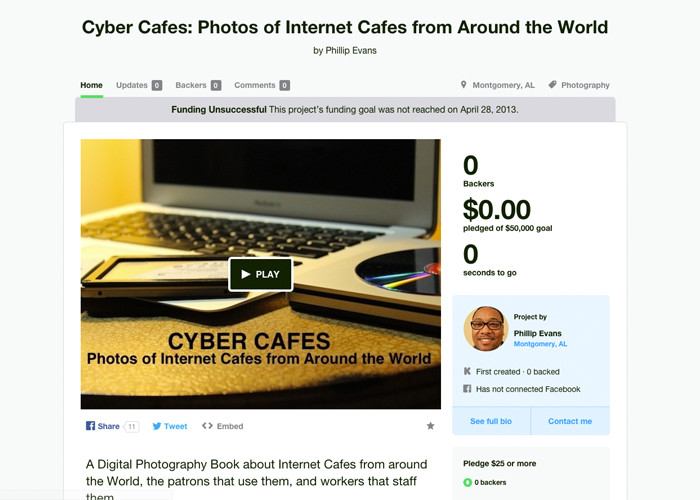

But I also came across ideas that I might have actually backed: for instance, I’d immediately buy a good photobook documenting the reality of internet cafes.

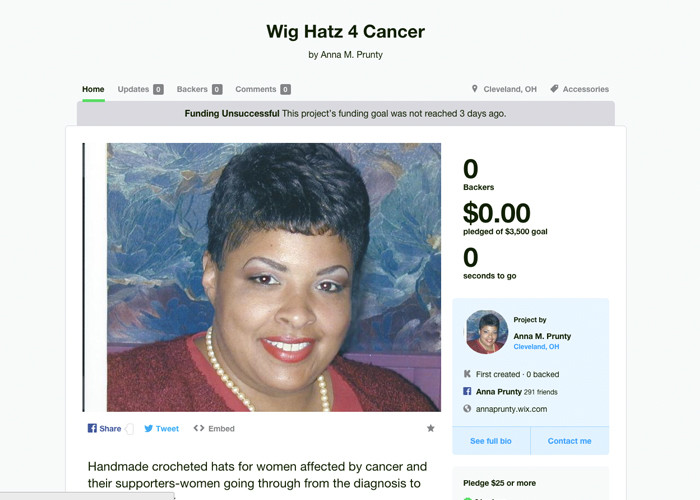

And I bumped into distressing stories, like the one of a breast cancer survivor who creates wig hats for “women affected by cancer and their supporters”.

Can't help but feel sad for some of these people whose dreams were crushed https://t.co/gyVdAuiQub. The rest is a lol fest of delusion

— pforpapa (@pforpapa) November 12, 2015

The reaction on social media was immediate. People found Kickended fun and sad at the same time. Some spoke about public shaming and schadenfreude. A few looked for their own campaigns.

Then, magazines and newspapers started to write about the piece. I did a dozen interviews with, among others, The Guardian, The Washington Post, and Wired. Generally, the last question was: “now that you saw all this, what are your suggestions for a successful campaign?” Kickended was now seen as a strategic asset.

Of all the articles about Kickended, the one I was mostly impressed by was a listicle published by The Mirror. Here, the editorial choice was to blur the faces and the details of the campaigns’ creators. For them, not getting any money was something to be ashamed of.

I’m not against crowdfunding, but I find it symptomatic of the anxiety that surrounds success and personal fulfillment. A kind of success that appears democratic and available to everyone. The fact that not even one user asked me to delete their record, makes me think that this anxiety is structural. It’s an external, societal pressure.

Many thinkers consider failure a good, necessary aspect of personal and communal growth. So, why is it so despised? I think it’s because failure is utterly incompatible with the eagerness to prevail in a competitive environment.

![]()

Nowadays, the catchiest narrative around success is produced within the universe of startups and tech entrepreneurship. Here, failure and success paradoxically blend: successful startups adopt the language of cooperation and inclusion to make-the-world-a-better-place™, but, to achieve this goal, they need to defeat their competitors. Failure is deemed natural, as long as it is someone else’s one.

Peter Thiel and his credit card.

According to Peter Thiel, co-founder of PayPal, startups behave like cults and the founder happens to play the role of the scapegoat. This doesn’t sound like an easy position to be in. I wondered how founders balance their optimistic public image with the inner structural pressures they constantly face.

More Peter Thiel stuff.

This question was the origin of the project I’m currently working on, entitled Fake It Till You Make It. Commissioned by the Goethe-Institut, it will be part of Streaming Egos, whose Italian pavilion is curated by Marco Mancuso and Filippo Lorenzin.

‘Fake it till you make it’ is a common expression in the world of startups, referring to the practice of pretending that the product is already functional while convincing investors. I’d like to show you a little excerpt of the video which will be part of the final installation.

My attempt is to employ the pervasive narrative of disruption and innovation to distill the tragic connotation of entrepreneurship. Jody Sherman and Austen Heinz had several things in common: they were both founders and CEOs of a tech startup, they frequented the same circle of ‘angel investors’, and they both committed suicide while leading their companies.

Anxiety, depression, and suicidal tendencies are common for entrepreneurs. But a dictatorship of optimism obscures the whole issue, like it does with failure. Last year, after those suicides, the startup community began to actively address it with services like Startup Anonymous.

Michael Freeman’s homepage.

Dr. Michael Freeman, a performance coach who works with CEOs, co-authored a study on entrepreneurs’ mental health. According to the doctors, “entrepreneurs create the vast majority of new jobs, pull economies out of recessions, introduce useful products and services, and create prosperity.” The study itself sounds pressuring. ”Prior research has identified the personality traits of successful entrepreneurs,” — they continue — “but little is known about the nature of their mental health characteristics or those of their families.”

I’m not an entrepreneur nor a startupper. Not even a maker. I’m a precarious worker split between the academia and the creative industries. Still, I think that the problems of this category concern me, since the entrepreneurship’s mindset is infiltrating both freelance and contract work, not to speak of social relationships.

Nowadays entrepreneurship seems less the result of a genuine desire of impact than a consequence of financial, affective, and professional precarity. The average Italian startupper is not 25. He’s 40 years old. Perhaps he can’t find a job even if he has a PhD. So, he tries to create a company with the help of Kickstarter.

“It’s lonely at the top…But it beats being depressed at the bottom.”

I believe that there is no qualitative difference between the stress of Silicon Valley’s entrepreneurs and the one of precarious workers turned CEOs. They’re both victims of the same ubiquitous monoculture. “It’s lonely at the top”, doesn’t matter if it’s a mountain or a little mound.

Where to find relief? Of course, techno-solutionism provides answers: plenty of self-help apps, remote counselors, WikiHow tutorials. In order to understand more of the ideological takes on this issue, I looked into popular declinations of therapies mostly based on mindfulness techniques and cognitive behavioral psychology. I’d like to conclude by showing you some of the things I’ve found.

With the help of ”meditation technology”, this website allows you to “‘reprogram’ your mind and feelings” to automatically attract achievements.

Meet Noproblemos, a persona representing an healthy mental balance. Of course, he’s planning to go into business.

And finally, if you feel less relaxed than 15 minutes ago, this is what Anxiety No More app suggests.

Thank you.

[My gratitude goes also to Alessandro Ludovico who came up with this title while reviewing Kickended.]