By Geert Lovink, first published by the Berlin magazine The Arts of the Working Class, here.

EU president Ursula von der Leyen wants Europe to tap into its inner avant-garde. In her inaugural State of the Union speech from September 16, 2020, she pledged to revive the historical Bauhaus – the experimental art school that married artistic form with functional design, founded a century ago in Weimar, Germany. Their objective was to democratize the experience of aesthetics and design through affordable commodity objects for the masses. Today, the European Union sees a chance to create a new common aesthetic born out of a need to renovate and construct more energy-efficient buildings. “I want NextGenerationEU to kickstart a European renovation wave and make our Union a leader in the circular economy,” von der Leyen said. The new Bauhaus is not just an environmental or economic project, “it needs to be a new cultural project for Europe. Every movement has its own look and feel. And we need to give our systemic change its own distinct aesthetic—to match style with sustainability. This is why we will set up a New European Bauhaus—a co-creation space where architects, artists, students, engineers, designers work together to make that happen. This is shaping the world we want to live in. A world served by an economy that cuts emissions, boosts competitiveness, reduces energy poverty, creates rewarding jobs and improves quality of life. A world where we use digital technologies to build a healthier, greener society.”

Putting rhetoric aside, this is the first time the European Commission launches a proposal to set up a network of (five) art schools. The European University Institute in Florence, founded in 1972, exclusively focusses on post-graduate teaching and research in the social sciences, excluding the arts and humanities completely. There are many EU affiliated research centres, but none of them comes close to the arts. Whether architects, urban planners and circular economy experts need such a green deal art school is something that needs to be discussed. What’s remarkable in von der Leyen’s New European Bauhaus, is that it goes beyond, yet is somehow related to the Brussels known research policy instruments such as STARTS but also Horizon Europe and Creative Europe.

Coming from a deeply federated Germany where culture and education is strictly considered a matter of the Länder (states), the European Bauhaus for the 21st century should be reworked and turned into a bold blueprint. What von der Leyen implicitly suggests here, is that Europeans need to come up with a new institutional form that can steer the ecological and digital challenges. Existing national art academies, design schools, technical universities and humanities departments have so far failed to come up with such a transnational concept. So far so good. We need new beginnings. How can art education become more relevant and cease to produce precarious artists, curators and critics? Contemporary arts can do a better than merely being a motor of gentrification of creative ‘smart cities’, in which real-estate is the only game in town. The arts can indeed play a major role in ‘societal challenges’—as problem accelerator. How can Bauhaus 2.0 sabotage the start-up logic of scaling up, selling out and creating new monopolies? It will be a radical task for Europe to face Silicon Valley venture capital rhetoric as a major obstacle for change. The aim of Bauhaus 2.0 cannot be to create a handful of European billionaires and even further increase inequality.

Von der Leyen’s proposal for a Bauhaus that could work on ‘creative’ solutions for the climate crisis can be traced back to the German climate researcher John Schnellnhuber. He founded the Potsdam Institute for Climate Research in 1992. It’s also said that the Berlin-based artist Olafur Elliasson was an advisor. In an interview in a German book on sustainability and universal basic income, Schnellnhuber talks about his Bauhaus idea and his hobby horse; wood architecture. [1] If he would become minister, he would found a “Bauhaus of the Earth” based in Brandenburg. For which he is already trying to find sponsoring, by the way. With this, he wants to return to a ‘polycentric’ organisation (which was destroyed by the Nazis), combining cultural theory with maker workshops that focus on materials – such as (surprise) wood. From an IT perspective Schnellnhuber wooden fetish marks an interesting ‘post-digital’ turn (and let’s talk about the latest invention of fluid wood here as well). Look at the artistic research done in the critical maker labs.[2] Here we see the digital and the analogue, the virtual and the real merging and colliding – overcoming old dualisms between material crafts and industrial abstractions. This is the material turn in digital culture (and vice versa). Long live digital materialism! We need to put the powerful digital tools that we have to work, to solve the planetary challenges humanity is facing. Through such a ‘digitization’ the growing gap between cities and countryside could also be reduced.

The deconstruction of the Bauhaus 1.0 ethic and aesthetic should remain an important background for any project that proclaims itself a new Bauhaus. Critique of modernism has been the task of the critical post-war 1968 generation. We can read entire libraries about totalitarian reality of the concrete urban deserts, designed by Le Courbusier clones. By now, we know whom the Bauhaus movement excluded and why, as well as the underlying philosophical logic that made it so easily adopted by forces that needed these exclusions. Most importantly, we should never forget why it failed to be a become the truly democratic artistic force it proposed itself to be. However, the fact that Bauhaus 1.0 was “inherently not inclusive,” as an open letter of the Maastricht Jan van Eyk academy claims,[3] should not stop us. We need to understand the political momentum currently providing a context of urgency to found a network of experimental interdisciplinary ‘green deal’ art schools. We live in the midst of the covid pandemic and the greatest economic recession since the 1930s afterall.

For inspiration about the digital side of the story we could go back to the Swedish Digital Bauhaus Manifesto (1998), written by Pelle Ehn, then founder of the K3 art academy in Malmö.[4] The author argues to bring together art and technology in a ‘third culture’. Ehn proposes to merge the hard with the soft – this time not through a modernist “solidified objectivity” but through a “sensuality in the design of meaningful interactive and virtual stories and environments.” Professor of the Copenhagen International Centre for Knowledge in the Arts and former Transmediale director Kristoffer Gansing remembers: “As a former student and employee of the K3 Malmö Digital Bauhaus I experienced both the best and worst sides of this model, which very much came out of a social-democratic and post-industrial vision of a future knowledge society. K3 was also born out of the first wave of mass digital and network cultures, which it wanted to imbue with a human-centred, socially aware approach. in dialogue with users, understanding digital interactive technologies and storytelling as methodologies to achieve this, not far from what today is known as ‘design thinking’).”[5]

In the late 1990s Malmö model the artist-designer was more of a mediator and producer than the creative genius of the Bauhaus generation. This is even more the case in 2020. The master-apprentice approach has long been replaced by an open, networked, distributed form of learning. This approach collides with the secrecy of the patent-based science approach and copyright-centric forms of knowledge production. Gansing believes K3 allowed for a new form of trans-disciplinarity to emerge, that is now the standard template for all the creative industries style educational programs that emerged in the past period. Gansing: “One could say that a thousand digital Bauhauses already emerged. K3 was good at breaking the elitism of art education in terms of admission. There is a class perspective here. K3, for example, was part of a new university in a largely working-class city, and this reflected in the way subjects were taught, opening up to the digital realm.” So, before we start to roll of Greta Thunberg Art Schools, it might be good to reflect on how the avant-gardist élan of the countless art & technology ‘new media’ programs quickly made way for entrepreneurial web/app design courses that catered for Silicon Valley platforms—instead of creating alternatives themselves.

Gansing concludes that “because of the massification and neo-liberalization of art and design art could now be integrated as a ‘creative’ element into all subjects, while not itself being a subject of rigorous study. It also largely failed at addressing the materiality of the digital on multiple levels, concerning the precarious conditions of digital labour and the need to build your own infrastructures.” In the current climate urgency debates we see a similar danger of instrumental approach of both arts and IT as fixed disciplines that are now required to serve and cater to the greater good—without being questioned or further developed themselves.

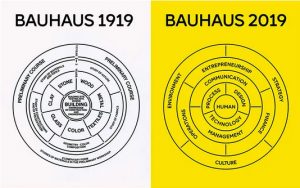

(original here at It’s Nice That, thanks to ref. of Silvio Lorusso)

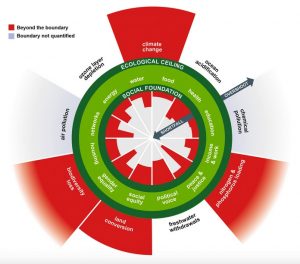

The critique that the historical Bauhaus wasn’t green, excluded women and did not make explicit post-colonial statements are easy to make. What’s important is what difference prototypes of integral education and research initiatives can make today. What’s important is if we’re able to organise the required multi-disciplinary forces to pull such a network of hybrid schools off the ground with a young, visionary staff, across entire Europe and beyond. In order to face the urgency of the ‘stack of crises’, we should find out how to zoom out, bring in difference, question authority, work on hard problems, avoid consensus at all cost, embrace the weird, and remain paranoid first. Dark ecology, the critique of platform capitalism and the history of racism and colonialism will only be few of the many first year courses. What will students make of such an Extinction Vorkurs? We urgently need the aesthetic equivalent of Kate Raworth’s donut economy and Marleen Stikker’s vision of the alternative internet, the public stack.[6]

visualizations of Waag’s public stack and Raworth’s Donut Economy

So, what happens when we start with Tim Morton’s ‘dark ecology’, instead of rushing into the ruthless promotion of ‘positive energy’ that ‘creative designers’ are supposed to express.[7] Criticality is something Europe should claim and be proud of. It is productive force that invites us to reflect and bring in other voices.[8] The emphasis on a positive attitude runs away from very real conflicts in society that need to be faced before we can start to implement blueprints. Ecological solutionism hides hard and urgent choices that need to be made and smoothens conflicting interests – turning conflicts into ‘challenges’ and ‘wicked problems’ that can be resolved through better branding and marketing. The network of ‘rainbow houses’ can do a better job.

In line with the pioneers a century ago, we need to stop building and create architectures (as the phrase said back then). This is a time of federated networks, inclusive code and public cables with the aim to support free cooperation between a multitude of players. Caught between the geo-political forces of the US and China, this what a resourceful European initiative should take up. Mixtures of art, science, education and public policy can hardly be called German. Quite the opposite. “This is the Europeanization of a German development model,” Max Welch Guerra commented in Politico.[9] And lest we forget: the staff of Bauhaus 1.0 was hardly German. The cosmopolitans had to flee for the Nazis and found themselves exiled across the world, spreading progressive concepts. However, what’s mostly remembered are the modernist architecture nightmares. Kristoffer Gansing: “Maybe the new reboot of the Bauhaus can work to correct some of this, but I have serious doubts. Rather it seems more like an acceleration of the already largely failed late 1990’s model. The difference is this Industry 4.0 dream that originated partly in German policy documents, tied in with a certain Make Germany Great Again idea of a modular, AI powered industry—now scaled up to the European level. But many of the same traps seem to be there, subordinating art to be the supplier of the right values and aesthetics rather than a force of change in and of itself, and here I’m not necessarily speaking of art with a big A but already about artists working in transdisciplinary ways and outside of the art market as well as the contemporary art world.”

The hard work of deconstruction will have to be recognized as an ongoing part of design and art education. While doing this, we should not get stuck at the level of identity. We should also extend this approach to the digital realm and apply ‘radical care’ methods to AI, blockchain and other ‘big data’ solutions. Instead of a mechanical implementation of ‘digitalization’ to all contexts, a more topical, tool-centred approach could be developed (one in which digital tools can be put aside once issues are resolved). Instead of data protection we can argue for data prevention. The growing reluctance to employ facial recognition software is a brilliant example of this turn. That’s privacy-by-design. Kristoffer Gansing puts it this way: “What is needed of a Bauhaus in the context of extinction is primarily a reparative work. The time for master-plans, however inclusive and participatory, is long-gone—nobody has the master-view any longer. Instead, we should aim for a granular-scale repairing of a world that is broken in so many respects, all the while treating this reparative art and design as truly transformative. This art and design school needs to undo a lot of existing structures, provide slippery and uneasy ‘solutions’ as much as new cultural imaginaries and material sustainability.”

Bauhaus 1.0 emerged from a similar crisis-ridden Europe. It created a new engineering style of the world from an economic, technical, social and artistic point of view. It understood the need for a new form of education, especially against the intrusion of authoritarian political movements. Their staff also had to confront a traditionalist, conservative establishment born out of the values of ‘old Europe’. To confront its mainstream institutions, that were ferociously trying to preserve themselves and dismiss such curious endeavours. This is the courage we wish for when we dream of a 21st century art and design education that, while facing our urgencies, dares to question, and dares to make a difference.

—

[1] Conversation between Adrienne Goehler and John Schnellhuber, in: Adrienne Goehler, Nachhaltigkeit usw., Parthas Verlag, Berlin, 2020, p. 337-338 (thanks to Florian Schneider).

[2] See: Loes Bogers & Letizia Chiappini (ed.), The Critical Makers Reader, (Un)Learning Technology, The Institute of Network Cultures, Amsterdam, 2019.

[3] Open letter to Ursula von der Leyen and Frans Timmermans, Objections to the term New European Bauhaus, https://janvaneyck.nl/site/assets/files/2899/letter_to_eu.pdf.

[4] Pelle Ehn, Manifesto for a Digital Bauhaus , Digital Creativity, 9:4,207-217, 1998, DOI: 10.1080/14626269808567128.

[5] Quotes from private email exchange, November 20, 2020.

[6] See https://www.kateraworth.com/doughnut/ and https://waag.org/en/project/public-stack-alternative-internet.

[7] Example could be René Kemp and Joost van Haaften’s policy brief, written in response to der Leyen’s Bauhaus proposal. “When done properly, the cause of contributing to a better world will spark and harness optimism, enthusiasm and idealism from professionals and citizens alike – not just for the energy transition but also for tackling the ills of the present economy. In taking a ‘building something better’ approach, the co-creation projects can be called Bauhaus (even though they are not based on Bauhaus architecture).” https://www.merit.unu.edu/building-back-a-better-world-a-plea-for-a-bauhaus-initiative/.

[8] See Mieke Gerritzen & Geert Lovink, Made in China, Designed in California, Criticised in Europe, Design Manifesto, BIS Publishers, Amsterdam, 2020.

[9] https://www.politico.eu/article/bauhaus-von-der-leyen-green-recycle/.