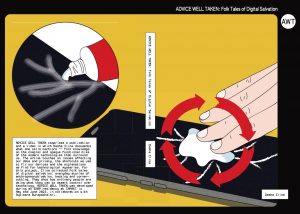

Dasha Ilina’s video work Advice Well Taken: Folk Tales of Digital Savation uses the ‘techlore’ concept to find out what ‘urban legends’ are in the age of smartphones. You can watch the ‘director’s cut’ of the video installation here. You can also have a look at a selection of the catalogue here. The 2023 Impakt Festival information about the installation can be found here. The essay was commissioned by Dasha Iina for the catalogue that came out in November 2023 during the Impakt Festival in Utrecht, where the video installation premiered. Read the ‘cookie conversation’ with the artist here, conducted by the Impakt Festival.

Tech is supposed to be scientific, neutral, transparent, objective–anything but a myth. After an initial phase of curiosity and excitement, systems crash, hacks and glitches take over and we enter a stage of frictionless 24/7 connectivity. Things look normal, but somehow nothing seems real. Technology does indeed break down and starts to act in strange ways, but still, you start to wonder. The screen just died. Did an animal interfere? Am I right that a ghost just appeared as a chatbot? Did someone pour water on my laptop? Neighbours must be stealing the signal. Can ancestors gain access to files? Why have I been unaware of invisible radiation and electromagnetic waves? Who told me to think of unicorns and dragons all the time?

Tech is supposed to be scientific, neutral, transparent, objective–anything but a myth. After an initial phase of curiosity and excitement, systems crash, hacks and glitches take over and we enter a stage of frictionless 24/7 connectivity. Things look normal, but somehow nothing seems real. Technology does indeed break down and starts to act in strange ways, but still, you start to wonder. The screen just died. Did an animal interfere? Am I right that a ghost just appeared as a chatbot? Did someone pour water on my laptop? Neighbours must be stealing the signal. Can ancestors gain access to files? Why have I been unaware of invisible radiation and electromagnetic waves? Who told me to think of unicorns and dragons all the time?

Over the past decades, mobile phones have not been considered part of popular culture. In the late 1970s, British ‘cultural studies’ unleashed an entire school of research into the appropriation of mass media products such as pop music, radio, film, television series and street fashion by its declining yet still confident working class. Forty years later, there is not much appropriation to be found among the 7.33 billion users of mobile/smart phones (data from mid-2023). Piracy no longer makes headlines, and cultural analysis of the smartphone seems to be at an all-time low. Not much counter-hegemony out there. Roland Barthes would have no doubt included the smartphone if he had written his Mythologies (1957) today. What’s myth creation in the age of fake news, social media dependency and deskilling under the influence of automation and machine learning? Is myth-making still centred around the relation between language and power, as in Barthes’ days? Have people lost their ability to remember and recollect stories in a comprehensive way? What is a myth anyway in an age when, due to the rise of technology, the power of speech is destined to decline, as Hannah Arendt already indicated in The Human Condition (1958)?

Let’s start the Arbeit am Mythos and dive into the stories Dasha collected.

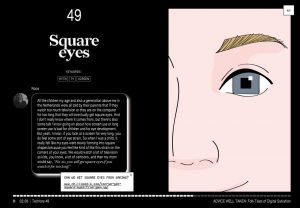

Roos: “Until recently I thought the square eye story was a universal myth, but apparently it’s very Dutch. People my age, but also the generation above me, that sat in front of the TV, were told by their parents that if they watch too much television (or the computer screen), they will get square eyes. I don’t really know where this myth comes from. There isn’t any hard evidence, apart from the correlation that children can get near-sighted. They may develop a focus on looking at things from nearby, that will mess up their eyesight. If you look at a screen for a long time, you do feel an eye strain. When I was a child, it felt like my eyes were slowly forming into square shapes, because you feel this strain on the corners of your eyes.”

The more users are online, the more start to become suspicious. With technical computer literacy on the way out, we instead experience the democratization of general uncertainty. All we do is manage our busy lives on multiple channels. What just happened on Stumble Guys? Let’s do this quick edit of the TikTok video with CapCut right away. Time to play Subway Surfers. Weirdness levels are on the rise. That the world is a boredom-killing theatre is fine. Ordinary procedures in a deeply chaotic world cannot be anything more than a lie. What’s left is entertainment and WhatsApp. The real existing catastrophe is inside the machine—mine. With so much popular eye candy and disbelief on display, negative dialectics will have to be on the rise. Adorno, where are you, now that we need you?

Taisiya: “I remember there were these waves, but not like electromagnetic waves from a phone. These were negative waves that affected your chakras. You had to keep your phone away from your body because it disturbed your internal energy. The waves became embedded and interrupted the waves that originated inside you. For me it always felt strange, like intimate physical contact. I didn’t take it as a myth or the truth, but some part of me really believed that these waves did have an effect on your physiology.”

The website Make Tech Easier lists ten smartphone myths you should not believe: that cell phones start fires at gas stations, charging overnight would damage the phone’s battery, that your phone could cook an egg, will demagnetize your credit cards, you have to drain the battery completely before charging it, that keeping the screen dim would be better for your eyes, closing background apps would make your phone faster, don’t use your phone when it’s charging not to drain the battery or use of a private browser that would protect your privacy. All this is not ‘true’, yet users believe en masse. Dasha Ilina is using the term techlore, defined as the everyday knowledge manifesting to us as information about how to use, fix, or hack technology. This type of information can be spread informally, whether online or in person, that we collectively use to improve our experiences with technology. Through techlore, we create a sense of regained agency over digital tools whose workings we ultimately don’t understand. Techlore blends genres, from pop folklore in the digital age to the anthropology of technology. Think of urban legends such as the 999 phone charging story which claims that calling an emergency telephone number and then promptly hanging up will charge phone batteries.

“Dasha: Do you use Face ID or sometimes there’s like fingerprint ID on iPhones?

Jolyn: Yeah, well I did it. I have it on my phone, the fingerprint, but the funniest thing is – I can open the telephone of my sister with my face.

Dasha: Because you look so similar?

Jolyn: Yeah!

Dasha: But you’re not twins?

Jolyn: No.

Dasha: Wow, that’s crazy! I’ve never heard that before.”

In Dutch these are called ‘monkey sandwich’ stories or ‘broodje aap’, a reference to the title of Ethel Portnoy’s 1978 collection of ‘folklore stories from the post-industrial age’. While most of them have a not-all-that-hidden sexual connotation, making them ideal materials for a psycho-analytic reading of popular culture, the stories collected for Advice Well Taken often lack the polymorph-perverse dimension that dominated the 1970s. There is a widespread awareness of the existence of dark forces inside the black box, but our approach seems to be a statistic one. The conspiracies exist, they are true and operational, but why should they exactly bother me? There is no destiny here, only probability. Contingency rulez. Better deal with it straight away, before an accident starts to attract more accidents. But what risks can we prevent when our life depends on code we can neither access nor read?

Monica: “My computer stopped working and then someone told me that the motherboard had just died. So I tried to recover it. Then I heard that if you change power voltage when you travel to another country that has 120V while yours has 220V, sometimes the computer dies for a bit but then recovers. I spent some time trying to fix it that way, by charging it and then un-charging it while pressing hundreds of combinations, I have a Mac, but it didn’t work. I don’t really know if it’s true that computers have this charger power confusion. They simply stop working. I know someone who had the same problem and it worked out for him. But mine didn’t come back to life.”

Compared to the Monkey Sandwich era, humor is lacking here (sorry, Freud). Mal-functioning tech is annoying and not funny. Most of us get angry at the gadgets, which can make other laugh… Folk stories from past decades that often circled around the danger of sex have been replaced by warnings for the hidden, dark side of virtual exchanges. What’s moving in the contemporary stories is the clumsy, do-it-yourself approach. YouTube instruction videos are hegemonic. Amidst so much dysfunctionality, planned obsolescence and lacking self-evidence, the ‘right to repair’ is widely felt, but what’s to be done when this or that app or device actually refuses to work?

The common element with the mythological stories from fifty years ago is the prominence of fear and paranoia. In her introduction, Ethel Portnoy emphasizes the presence of a half-way processed or rather a wrong understanding of science. Kali is dead and no matter what religion will help us out. This is also the common belief of Christian atheists. Nietzsche’s insights are taken for granted by the online multitudes. What we have to deal with are tiny, invisible forces, coded Trojan horses, that take aim at us. The Lord may judge his people (Hebrews 10:30), but who will deal with software compliance?

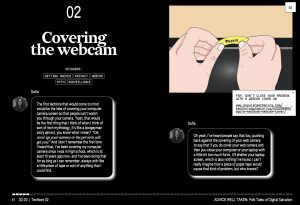

There’s a lot of local truth inside that phone—our ultimate mythological device. A friend called Sofia inspired Dasha Ilina to start Advice Well Taken. Over the past decade, Sofia told Dasha many ‘urban legends’ that seemed incredible One day, Dasha invited her over to her Paris apartment and recorded the conversation. This first one also turned out to be the longest recording. There are six clips with Sofia, each consisting of one story. The very first clip dealt with the myth of covering your web camera on your laptop so that nobody can hack it and watch you through it. Sofia was adamant: “Cover up your camera or the perverts will get you!” Sofia has been covering up her camera ever since she was in high school, even without knowing how that, technically speaking, could be done. “I’m not taking any chances that somebody is going to see me, you know, dancing naked in my apartment.” Sofia also referred to elements in television and film where the camera is activated remotely and the main character is being blackmailed with compromising content. Sofia: “I was also told that if you do cover your web camera and then you close your laptop with a little bit too much force, it’ll shatter your laptop screen.”

If the function of myth was once to naturalize concepts, what’s being promoted in the collected cases presented here? We often find people and their tech stories moving. We feel for them. Users are neither stupid nor ill-informed. We do not feel ignorant, but rather clumsy. Everything can and will be explained in a how-to YouTube video… but that’s not the point. Our busy lives are collapsing under the weight of complexity, and we have to make up stories about how we’re somehow dealing with the dysfunctionality of the world. Thus techno-myths are condensed stories that travel through time and space, and bear witness to our dealings with the nasty interplay of promised perfection and real existing breakdown. Confronted with automated processes, layer over layer, we search for vital signs that the machines will reveal to us.

Sofia prefers to go to the real people online forum of the quasi-professional how-to sites over professional advice: “I really love using Quora or Yahoo Answers! I have obviously, like everybody, never contributed to the canonical texts of Quora and Yahoo Answers, but some users 9 years ago will have had the specific answer to the problem that you have. Often the first thing that comes up is an article written apparently addressing your problem or sort of promising to answer your problem, which may fall into like a series of problems related to the same thing, and then frequently I feel that I don’t find the answer that I’m looking for and that the article is just full of, how would you call it – search bait terms? You know, things that make the article come up on Google more often because it hits certain keywords which is not super helpful, and then you scroll down and there’s the Yahoo response being like ‘Hey man 😉 I went through this problem very recently’ and it’ll give an in-depth explanation of exactly what happened and how to do it and then that’s it. You know what I mean? There’ll be one response, but it’ll be the one. It feels a lot more human, I think, than the keyword-focused articles.”

Sofia also came up with a pet conspiracy theory about Instagram filters. The reason why these apps ask you to open your mouth or eyes, turn your head, nod yes or no, is to gather these data to create large databases on how human faces move. “I felt for a long time, that Instagram filters are creepy and not something I feel comfortable with using, because they’re a palatable way of advancing facial recognition technology. They’re trying to identify a criminal through a picture caught on a security camera, but that’s very difficult to do. If you could have an interpretation of the way somebody’s face moves and not just use a flat two-dimensional image, that movement is as unique as a fingerprint – the way somebody’s eyes and mouth move when they speak, recorded from different angles, like up and down, because often I think that can be very difficult – identifying somebody from their side profile or from an angle that isn’t head on. And it feels like a cutesy, palatable way of making that happen from an enormous data set of people who use this technology. That’s always made me a little bit uncomfortable.” Then Dasha asked: “Do you use Instagram Filter nowadays?” Sofia answered: “Sometimes because then… fuck, I’m like a slave in the same way that everybody else is, like I really go out of my way not to like… I always, always hit ‘reject all’ when asked about cookies, but sometimes I am a slave to convenience.”

In the absence of a Big Signifier, be it God or the Communist Party, 21st-century tech myths seem deeply secular, unspectacular, half-baked or, at best, mundane. No trace of eroticism or mysticism. Where are the miracles? The heroes? Is Barbie all there is? What we’re left with is the hippie-manqué ideology of Bay area Big Tech. Badness in the absence of Evil. Unlike the 20th-century fights over the role of avant-garde movements about the Big Party, large-scale controversies that end fragile coalitions and cut up into friendships utterly fail. While family ties and friendships could break up over (social) media fabricated issues such as wokeness, abortion, climate change, COVID-19 vaccines or lockdown measures, this is not the case with tech issues such as the wide use of extractivist platforms and AI. For George Bataille, ‘the absence of myth’ had become the myth of the modern age—and this is where we stand today. The night is also a sun. The world has lost its secrets, and thus its cohesion. L’Expérience interieure is an empty folder. All we’re left with are small tech inconveniences—that drive us nuts.

Let’s switch to Patrick. He told Dasha: “Nowadays, there are energy coaches because of the soaring energy prices. Someone comes by and listens to your story, inspects your house and the insulation and then gives advice about energy use. They have free aluminium foil to put behind radiators etc. I told them I had a new Wi-Fi router installed in December last year and it’s working all through the house. I was talking to the person who installed it that I would love to switch it off at night because it’s warm and it has a little light, so it uses energy, and I said it to the internet energy coach and she said “yeah, well it’s uses very little energy, but it gives off this radiation.” Now Patrick also switches off the Wi-Fi at night, not because of the energy, but because of radiation. I was I was thinking “What? What radiation?” We’re surrounded by radiation, every radio picks up radiation, that’s why it’s called a radio. And in the background, there was what we call ‘broodje aap’, pseudo-scientific stories of someone who put a story out on the internet about a plant they put in front of the Wi-Fi station and it died after two weeks. And then they put the plant somewhere else and it didn’t die… But that’s not scientific, that’s just bullshit.”

While great stories such as the Greek myths may lead us through the journey of life, giving meaning to becoming and loss, the absence of myth may not even be the greatest tragedy. What’s lacking is the ability to collectively express the shock. Faced with the absence of all ideas and poetic revolt, the world shrinks to the coldest, purest proportions. What happens when automatic writing turns out long strings of emojis? Can we still call in psychoanalysis for help? Does a universe without myth turn that universe into a ruin, as Bataille stated in 1947?

Next is a conversation Dasha had with her parents:

“Milena: We don’t really believe in conspiracy theories about phones spying on us, but of course, I think there’s some truth to it.

Sergei: There is some truth in this, maybe someone is not following, but..

Milena: Listening.

Sergei: Yes, not listening, but in any case.

Milena: Well, artificial intelligence is probably there.

Sergei: Objectively. there is some sort of a database, the accumulation of a certain database, right? About users and customers. That’s the new oil. Accordingly, no one is arguing with this anymore and it probably can’t even be called tech-techno, you can’t call it techlore, it’s already an established fact.

Dasha: Even if something’s a fact, I still consider it techlore.

Sergei: Okay, yes, okay. It’s, it’s a fact.”

Can only what’s dead be fully understood? Apparently not. The Zizekian Law of False Consciousness has migrated to the next level: a second-order Zizekian ideology in which all subjects have fully understood Zizek’s teachings. They fully admit that they’re living within the algorithmic confinement of the Big Tech cave, and have deconstructed its workings—yet still obey and are even eager to confess this as a ‘fact’ of life. We live inside the tech ideology, and Zizek is precisely Europe’s most popular philosopher because he helps the YouTube generation reconcile with this ‘fact’, admitting the sins of capitalist sublime seduction, while calling it by its name. This is everyday dialectics by the online billions, a deep dialectic culture on a scale that Hegel and Marx could never have anticipated.

“Milena: When I go to bed, I make sure I put my phone in the other room. I don’t know why, but I put it there. I have the idea that it gives off some kind of radiation so that it doesn’t interfere with my sleep.

Sergei: And Milena also turns off the Wi-Fi at night. Milena: I also don’t know why, maybe because it also gives off some kind of radiation. From the modem.

Sergei: Yes, yes, that’s the reason why.

Milena: I also rarely put the phone close to my ear. Even if I’m talking somewhere and I can’t put it on speakerphone, I’ll keep it at a distance, because someone once told me that if I put it right up to my ear, I will get problems with my brain.

Sergei: I do the same thing voluntarily or involuntarily, because we live together, right? All habits are replicated quickly, they spread fast, It’s the same here, willingly or unwillingly. We don’t have a TV at home and we don’t have a microwave, so we’re really immersed.

Milena: We don’t even have an induction stove, which is supposed to be really fast, because there might be some kind of radiation from it. We don’t know what kind.

Sergei: Not to say that because we don’t use these things we suffer. Anyway, we’re sufficiently modern and live in a modern society, but there are certain things. Yes, there are such moments.

Milena: Well, probably because our life doesn’t really depend on these things. Why would you need a TV when you have a computer?

Sergei: Right.

Dasha: So, there’s no radiation from the computer, but you can get it from a TV?

Milena: No, from a computer there cannot be radiation, because we use it.

Sergei: Yeah, and there’s a 25th frame on the TV. Everyone knows this, it’s a known fact, the 25th frame, turning people into zombies. This is all really well-known. A well-known fact.”

In his 2023 essay Krise der Narration, German philosopher Byung-Chul Han blames modernity for the destruction of telling stories in favour of ‘storyselling’. He maps out humankind’s march from story to information. The inflationary emphasis of commerce on ‘storytelling’ merely hides the fact that stories have lost their magic. Their ‘inner truth moment’ has vanished, says Han. The destruction of distance has made it impossible to tell stories about unknown exotic outposts. The post-colonial gender attack on ‘his’ story does the rest. Social media timelines have replaced the ‘narrated life’. Only the moment counts. The time of the digital regime is one without inner life. People can only speak in half sentences and phrases and are no longer able to tell coherent stories to each other. Users merely exchange condensed references to online info particles they read or heard ‘somewhere’.

“Dasha: Do you want to talk about the 5G conspiracies that you’ve heard and what people think?

Martha: Something about how it’s bad for your health. Some people do not want to have their phones in their bedrooms because they fear it acts like a microwave and is going to affect your brain or your heart. Definitely that 5G can cause all sorts of things.

Dasha: Do you do that? Do you leave your phone in another room?

Martha: No, I sleep with it, I have it like under my pillow.

Dasha: Really?

Martha: Probably, I just really want to get it in my brain, don’t I?”

While there’s pleasure to be found in the consumption of German contemporary pessimism, we also need to move on and not dwell on some lost human capacities. Nonetheless, there’s so much Han truth per page in there, neatly packaged, ideal for delayed train journeys, ready to be printed on t-shirts, caps and coffee mugs. We seem ready to advertise our spiritual defeat. Live or Post. “Die Intelligenz rechnet und zählt. Der Geist aber erzählt.” ( the intelligence calculates and counts,yet the spirit narrates) A gay science perspective on all the too human character traits would, on the other hand, emphasize the lively speed of exchanging references to compressed fragments, a ping-pong chat that seeks irony, not depth. That’s our Kultur. We’ve gone from why to just because. The enchantment of the world is a closed chapter and, is something the postmodern multitudes simply cannot reverse. Stories may create social cohesion, but we’re too weak to get rid of our phones. Instead, we play summary games, exercising the art of rapping narrative debris, packed with today’s news items, memes, popular sayings and one-liners from lyrics or a Netflix series, interrupting the other with even more half-baked myths and third-hand information someone heard on the socials.

Let’s also end with Roos and her Instagram advertising story. “A lot of people that use Instagram have the feeling they’re being watched, as personalized advertising gets very specific at times. A lot of people think they are being listened to through their phone’s microphone. The myth is very strong, but Meta, Instagram’s owner, denies it vehemently. There’s also that little dot showing up on your screen whenever your microphone or camera is being used. They reassure you that your microphone is not used, yet the feeling doesn’t go away. The thing became so big that the biggest Dutch news media platform NOS did an entire research and bought a completely new phone, putting it next to a speaker that was saying words like baby products, diapers, and baby bottles to see if the Instagram profile would gear towards baby products, but in end it didn’t work. Yet the feeling is still there. So I turned everything off on my phone, do not track, etc. Then this week I was sitting on the train and at the next stop a guy came in. He was wearing crazy shoes I have never seen them before where the toes are separated in the shoe. And I was looking at the shoes like ‘wow, that’s a choice, that’s interesting!’ I was mesmerized, but I only thought of the shoes. I didn’t talk about the shoes with anyone, I didn’t look them up on the internet. The next day Instagram showed me an advertisement with these exact same shoes. That freaked me out.”