A Series of Conversations with Designers, Curators, and Program Makers

The start of this new decade has not turned out the way many expected or hoped for. In an increasingly globalized world, a sudden halt to mobility seemed unimaginable. From ‘the world is your oyster’ to being forced to stay confined in small bedrooms for months on end, a lot has changed overnight. The pandemic has forced people to suddenly move their whole life – work, dinners, celebrations, relationships, and cultural activities – online. As a culture professional with a fascination for media arts and online exhibitions, I follow the roads the cultural sector travels in transforming their programs to online with open eyes. It’s a road full of technical bumps, many forks that need apt decision making, and some U-turns ending up back in the 90s. From exhibitions, panel discussions, lectures, workshops to entire festivals, what was once a sector that took place mostly in exhibition spaces, conference halls, and event locations, now is confined to the two-dimensional screen.

We are still in the middle (or at the beginning, who can tell), of these developments. Once the pandemic has come to an end, the initiatives might get lost in the endlessness of content online. Maybe we will come together and laugh at the time that our lives were spent online, telling anecdotes of our experiences in confinement – only to conclude: never again. Yet, there is much to learn from what is happening as we speak. More likely than not, online or hybrid events will stay around for a longer time, during and after the coronacrisis.

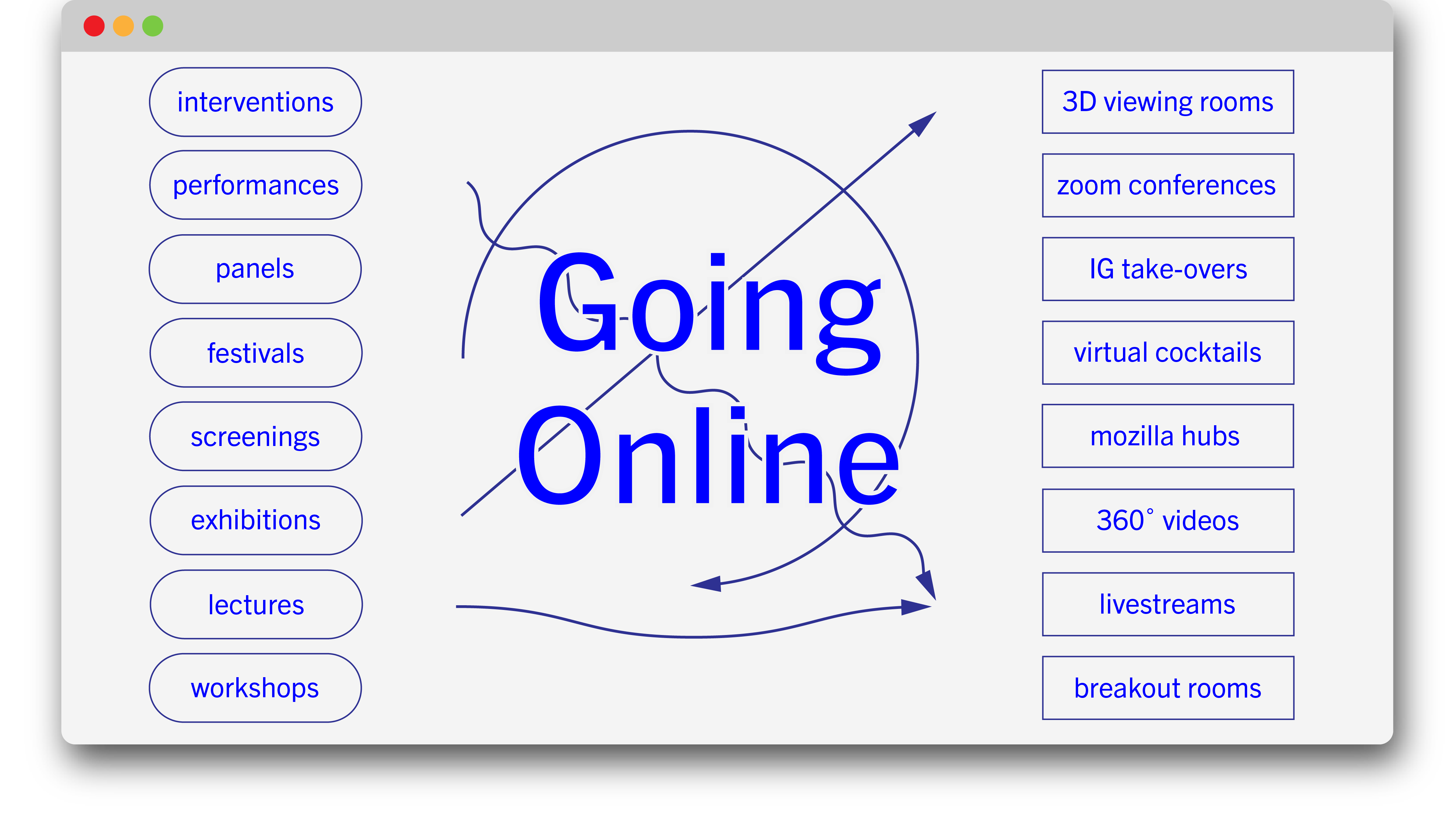

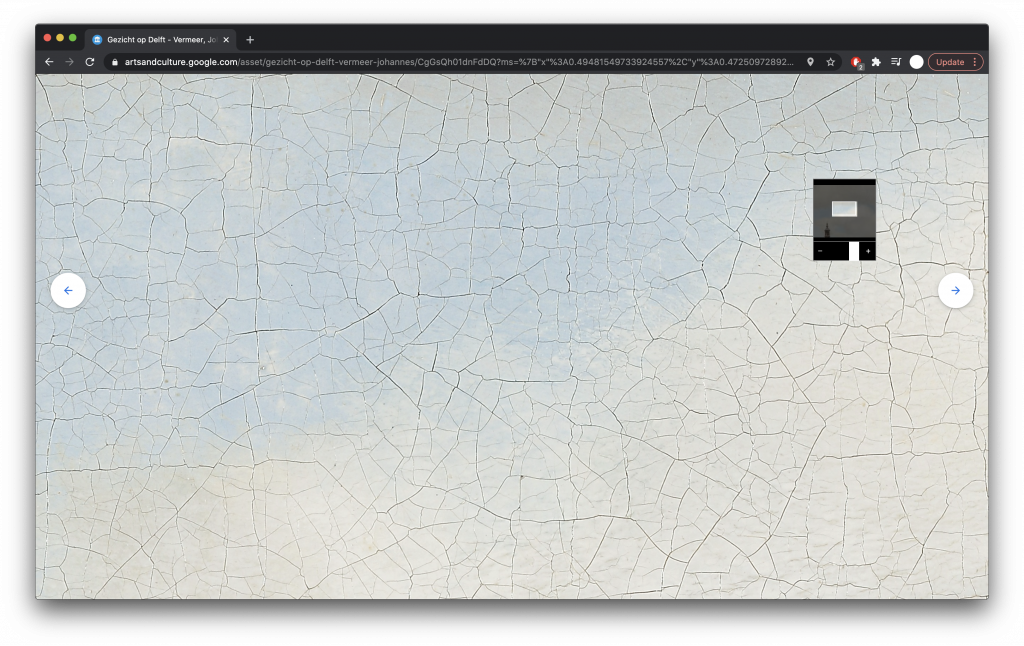

What are the possibilities of Going Online? Giving digital formats a quick thought might result in a range of possibilities – fewer costs for production, spaces, and storage leads to endless amounts of content that can be available for an infinite amount of time, reaching a global audience effortlessly at the click of a button. Particular possibilities are heightened, such as zooming into an artwork in Google’s Art & Culture. A guard would have already told you to keep the appropriate distance to the artwork in a museum. When it comes to digital formats, is the sky the limit?

Exploring HD artworks with Google Arts & Culture, zoom level 75% into Vermeer’s Gezicht op Delft.

Simultaneously, doubts arise. Content is one aspect, but what about the liveness of digital formats? How can an online event feel as lively as its physical counterpart used to be? Does drinking a beer at home alone behind your device taste as good as in the event’s bar? How can communities come together and participate when, more than 1.5 meters apart, they have to bridge new distances? Roommates or partners in the background of the call, classic Zoom fatigue, and the ever problematic attention span that comes with knowing you could be doing anything and everything else while joining into a digital format – there is a lot of distraction.

Metaphors

These digital event formats often borrow metaphors from older technologies or physical spaces. In her publication, Marianna van der Boomen investigates the metaphors of digital software, functions, and concepts with which we interact in our daily lives in her publication Transcoding the digital, how metaphors matter in new media. From e-mail ‘mailboxes’ to application ‘windows’, she follows the traces of metaphors as actors. Discussing the complex systems which shape and are shaped by metaphors, she says

I consider digital-symbolical objects as an onto-epistemological riddle because they are neither pure objects, nor pure symbolic forms, nor pure digital patterns. They are hybrids of computation, algorithms, and language – artifacts cut out of arbitrarily assigned numbers, processed by machines and humans, represented, symbolized, ontologized, and incorporated in the social texture. The riddle then is: how do such composites of numbers and language, of algorithms and discourse, of computer code and cultural code, come about and get stabilized? – Marianne van der Boomen[1]

What metaphors do organizations use to translate cultural formats to virtual ones, how are they shaped, and how do they shape the formats in turn?

A recurring metaphor is the television one, as a lot of these digital events manifest as live streams on a screen. The basics are nearly the same for everybody: video and audio are (live)streamed, the audience can ask questions in a chat or by dial-in, a moderator or host guides the speakers, a team of technicians makes sure everything runs smoothly. Television has been doing this for years and years already – cultural organizations (not always equipped with the right space, technology, technical expertise, or budget) have to adapt quickly.

Strategies

How to meaningfully translate content online is almost a trick question. With limits to time, budget, and technical expertise, only so much is possible. The alternative would be not to have a cultural sector at all and wait until the lockdown is over. Is not showing something a better alternative than showing something imperfectly? More than a question about ideals, it’s a practical reality. How about the fees of the people involved, creatives and freelancers who have to pay the bills? Organizations can not shy away from this social responsibility. As has been pointed out repeatedly in the past months, a lockdown wouldn’t be any fun without music to listen to, books to read, and films to watch. Culture is urgently needed, maybe even more so nowadays.

Going Online is a matter of necessity for some organizations, a way to reach their publics who are confined to their houses. It is not something desirable. Never meant to substitute the real event, it is a forced solution to seek ways of bringing the work of artists, designers, and thinkers to its audiences. For others, the pandemic has only emphasized the need for Going Online, a strategy that was already on the agenda for a longer time. Specifically for media (arts) organizations, it makes sense to (also) present their programs convincingly on the internet, and in doing so reach new global audiences.

These processes of making new content and translating existing content are by no means homogenous ones. Similar to how these events have tailored to their specific audiences and have worked based on their own expertise and vision, their online afterlives are as different and varying as their pre-pandemic counterparts. Not one solution fits all.

A quick look at the productions of cultural events in the Netherlands in the past year gives a breath of different strategies. A selection of events: Dutch Design Week ‘went online’, resulting in 3D Viewing Rooms, 360 degrees museum walkthroughs, and DDW TV. IMPAKT Festival provided lectures, panels, workshops, and films from their self-made web portal. Framer Framed teamed up with Amsterdam Museum for the online exhibition Corona in de Stad, an ongoing collection of photos, videos, texts, and audio fragments about the experiences of the coronacrisis period of people in Amsterdam. MU’s exhibition Self Design Academy took place in hybrid formats, in which online work complemented the physical exhibition. The Hmm set out to find the best platform for online events – Jitsi, Zoom, Twitch?. Varia’s Century 21 Calling – Party Line – Stream discussed the history of the videochat tracing it back to the 19th century. Of course, the past year showed many more events that in format and content reflected on the quick shift to the world wide web.

Varia tells it like it is on the event page of Century 21 Calling – Party Line – Stream.

Some strategies anticipated on an online or hybrid character. Others had to adapt quickly to new measures and were more reactive. What were the aims of these different events? How can the strategies and processes of Going Online become sustainable? Which choices were made along the way and why? Can and should the content stay available afterward? And if so, how do you create an archive that is lively and interesting?

Experiences

Next to metaphors and strategies, this series questions the experiences of digital events. Whereas the first corona wave still saw people excited about coming together online, much of the enthusiasm has died after months and months of online social lives. The other day a friend apologized for not texting me back. She told me that the joy of meeting up with a person and spending time with them to catch up fades out once social contact become a selection of ‘hey how are you’ messages back and forth at a continuous yet constantly disrupted pace. Similarly, the social aspects of cultural events changed, and there is a need to look for new forms.

These events can turn out to be very fun and playful, but also lonely. What are exciting ways to connect? How can visitors interact? How can an organization maintain a community online or add new audiences to their existing community? What are ways to keep up the energy level during an online event, both for the ones presenting as the ones watching?

Going Online

These and other questions will be posed, reflected upon, and answered throughout the upcoming blog series. The title, Going Online, refers to the phrase we’ve been surrounded with lately, stating ‘X is Going Online this year’. It also refers to the act of connecting to the internet as an audience, what used to be referred to as ‘surfing the web’ (yet another metaphor that speaks to the imagination while evoking imagery of the internet as an endless ocean).

The list of digital events that I will discuss in this series is by no means exhaustive, as nearly every art institution and non-institution had to deal with the challenges of translating their programs into a digital version. Although I recognize that digital (art) events and experiments go back way further than the start of the pandemic around March 2020, this series focuses on festivals, events, and exhibitions that had to transfer their practices to online environments in the course of the last year. By having conversations with designers, curators, and program makers, I attempt to provide various perspectives on the topic of medium translations. Finally, these insights come together in a first attempt for ‘Towards a Toolbox for Going Online’.

References

[1] Marianne van der Boomen, Transcoding the digital, how metaphors matter in new media, Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2014