Motel Spatie & Zinedepo

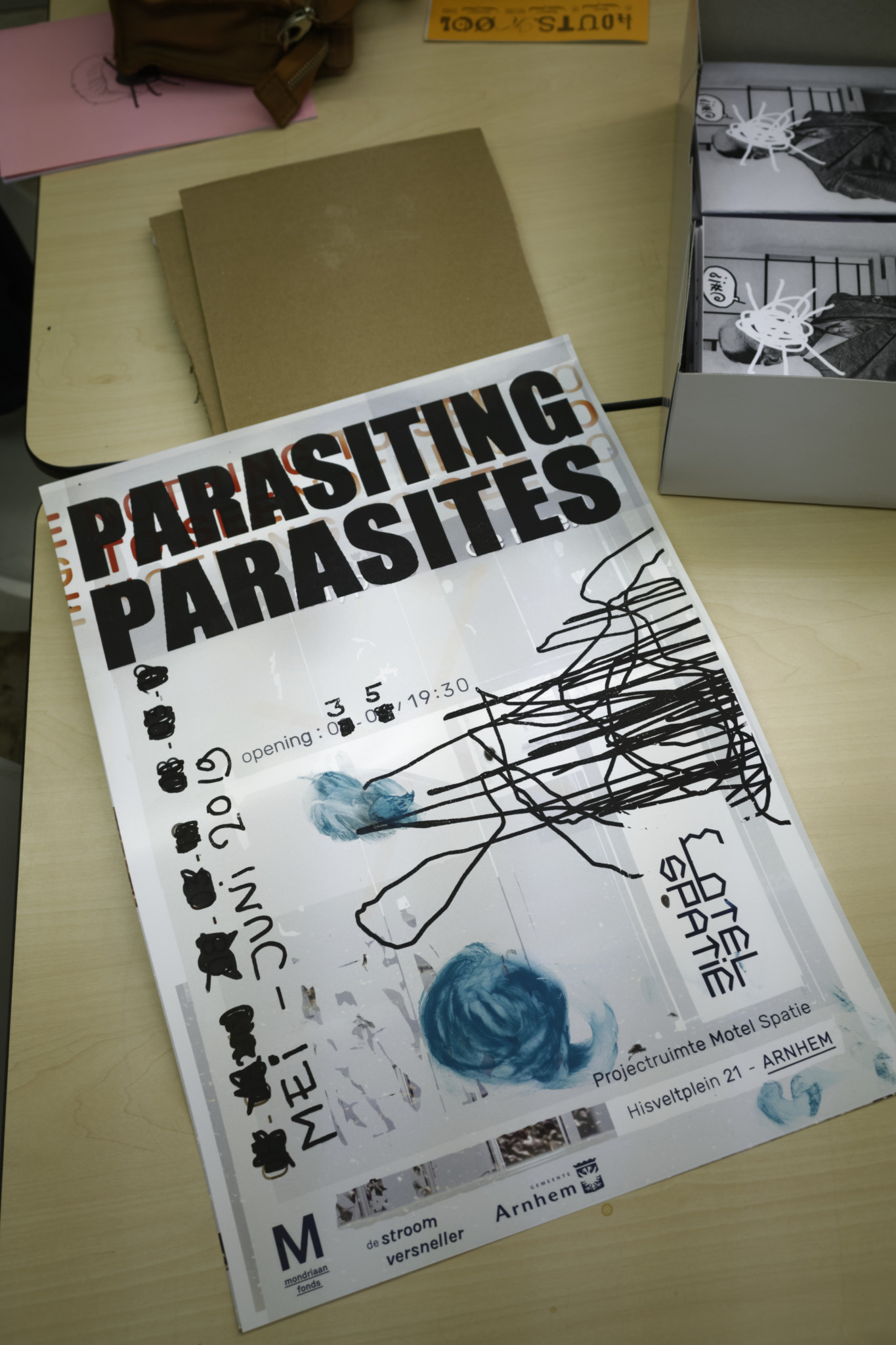

This part of the Urgent Publishing conference took place as a parasitic event at the artist-run space Motel Spatie in Arnhem’s working-class suburb Presikhaaf. Claudia Schouten, Motel Spatie’s founder and artistic director, explained that the modernist buildings of this neighborhood were built post-WWII from war debris. In the last few decades, Presikhaaf transformed into a migrant neighborhood.

Motel Spatie is located in a part of an abandoned shopping mall. The mall had been built in 1965 as one of the first European adoptions of the American shopping mall concept. Motel Spatie is a DIY space founded in 2010 on the principles and with the attitude of squatter culture, never mind squatting having been outlawed in the Netherlands by the neoliberal Rutte government.

People’s kitchen @ Motel Spatie

Motel Spatie’s members renovated and reconstructed the building without a license and got city officials into embracing it, have never paid rent for the space, obtained art funding for the first time in 2013 and began a residency for artists from abroad. The 2016 Sonsbeek Biennial (Arnhem’s famous biennial for open air sculpture) got Motel Spatie recognition for the first time because its curators, the Indonesian Ruang Rupa collective, immediately understood what it was and appreciated its way of working.

Parts of Motel Spatie are the people’s kitchen, a squat-style eatery that serves excellent yet inexpensive Indonesian food, and Zinedepo, a collection and public library of more than 1200 international zines (i.e. small-edition, inexpensive DIY periodicals), founded and maintained by Marc van Elburg.

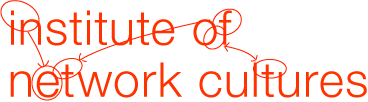

Zinedepo

Van Elburg has been a zine maker and zine collector since the early 1990s. He is also an experimenter with generative/rule-based zine making, and a zine theoretician. His Zinedepo manifesto of radical zine culture clarifies Zinedepo’s overall understanding of zine culture in between (a) 1980s/1990s zinemaking as anti-mainstream, countercultural publishing and (b) today’s zinemaking renaissance where zine culture positions itself as an alternative to the Internet (particularly, to blogging and social media), often emphasizing the handmade, visual and material qualities of its medium. Here, the Zinedepo manifesto sees the danger of fetishizing and over-designing:

The radical zine format is basic; several pages, black & white, folded and stapled together. Zines = zineculture Zineculture = proto social network. The radical zine format is not about printing and printing techniques (but its content can be). The radical zine format is not about bookmaking (but its content can be). Zines are about social networking (global and local). Most zines have an ‘open structure’, (this way they are also a network of meaning). The radical zine is primarily about personal interest (from the individual to the general). Radical zine ideology is ‘do it yourself’ ideology. Radical zine culture is not technophobic; a robot may produce and promote a zine completely automatically as long as it is a product of its personal expression.

As long as the definition of the radical zine format is (more or less) maintained, there is no limit to subject matter (sex/death) or to discipline (drawn, written, collaged, cut & paste, scratched, photographed, coded, etc.)

The radical zine format is not a mass product (but many people may copy a zine) The radical zine is not Art (but its content can be) Radical zineculture = Canadian culture

(some of the elements of the manifest have no function but to separate zine-culture from any other culture. A tongue-in-cheeck reference to South Park ‘the royal canadian wedding episode’.

The manifest is not so much a set of rigid rules but a coordinate. It more or less gives our definition of zines as opposed to art books or magazines).

In researching radical zine culture, van Elburg became interested in the notion of the parasite and parasitic publishing. In his book The Parasite (originally published in 1980), philosopher Michel Serres suggests to rethink the relations between humans and parasites: “We parasite each other and live amidst parasites. Which is more or less a way of saying that they constitute our environment”.1

For van Elburg, the concept of the parasite is thus opposed to the ideology of autonomy and freedom as it is nowadays promoted by right-wing populists, because from a parasitic perspective, we are never free but live in complex systemic dependencies. The interrelation between parasite and body is so deep that separation would be deadly. The negative connotation of the “parasite” thus needs to be turned around, and “parasites” need to be thought of as positive forces.

In this spirit, the Urgent Publishing symposium parasitically dwelt on Motel Spatie’s and Zinedepo’s symposium. The Synchronicity of Parasites had namely been independently thought up and organized by van Elburg. Only at a later point, and thanks to an incidental overlap in time, Urgent Publishing made it part of its own conference program.

Zinedepo during the symposium

The speakers of this mini symposium were Anders M. Gullestad, associate professor at the Department of Linguistic, Literary and Aesthetic Studies at University of Bergen, Norway; Anna Poletti, associate professor of English Language and Culture at Universiteit Utrecht; and Wilfried Hou Je Bek, – among others – zine maker, writer, squatter and psychogeographic computationalist and game developer.

Anders M. Gullestad, On the Emergence of Humanist Parasite Studies

Anders M. Gullestad introduces parasite studies as something that became his own endeavor and academic specialization through his PhD thesis in literary studies. According to Gullestad, there are a number of negative, often political attributions of “parasite”. For example, both capitalists and socialists have been called “parasites” by their respective enemies. The literal meaning of the word, however, is someone who sits at a dinner table next to the regular guests and eats the food. Gullestad attempted to apply of Gilles Deleuze’s concept of the “minor literature”2 to the concept of the parasite. What began as an investigation of postmodern American novelism eventually focused on Bartleby’s “I would prefer not to” and its adoption as a political slogan for Occupy Wall Street in 2011. Bartleby and his famous phrase have been read and interpreted, among others, by Giorgio Agamben, Maurice Blanchot, Gilles Deleuze, Jacques Derrida, Michael Hardt, Isabelle Stengers and Slavoj Žižek.3 Bartleby has been interpreted as a corpse or ghost, as a slacker, schizophrenic, the narrator’s double, a symbol of artists under marketplace conditions, as the patron saint of writers who stopped writing, as an exploited proletarian or even as a revolutionary.

Anders M. Gullestad

While there are several scholarly readings of Bartleby as a parasite, he actually does not feed on anyone or anything. Yet “[n]ot eating, not even being hungry, is erasing oneself as a parasite” (Serres, 109). So maybe the narrator himself is the parasite, feeding on Bartleby, and resulting in a symbiosis of parasite and host? Alternatively, the formula “I would prefer not to” could be seen as a parasitic meme, spread via Bartleby, with what Gullestad calls the “Bartleby [interpretation] industry” being its performative proof.

Next to Serres, Jacques Derrida, the literary scholar J. Hillis Miller and the evolutionary biologist Leigh van Valen4 reflected on parasites. The scholarship on the subject exploded after 2000. Gullestad therefore imagines Humanist Parasite Studies as a new field of research spanning literary studies, philosophy, sociology, anthropology, film studies, media studies, cultural studies, art history, linguistics, theology, classics and more. However, this comes with a number of issues and challenges:

- The question of metaphoricity: when are we literally or metaphorically referring to parasites? – To give an example: calling plants and animals parasites is a historically much newer phenomenon than calling people parasites, and therefore more metaphorical.

- The question of ethics: how can one revise the stigmatization of parasites without falling into the opposite extreme of glorifying them? How can parasites be made productive and not simply remain in a pejorative realm? An example of this are colonial languages that are, in the most literal sense, parasitic languages.

Since parasites are always with us, cannot be avoided, they are not a matter of good or bad. They disturb and upset control and therefore disturb hierarchies.

Anna Poletti, The Synchronicity of Feminist Parasites

Anna Poletti introduced herself as a literary scholar who does not study what is canonically recognized as literature, but marginal publications such as zines. Poletti relocated to the Netherlands from Australia where she had been involved with one of the world’s longest-running and (within international zine communities) most famous zine spaces, Sticky Institute, which is located in a pedestrian underpass in Melbourne’s city center. Prior to her talk at Motel Spatie, she had published her manuscript as a zine and distributed it among the visitors who were invited to read along her lecture. It began with an autobiographical account of meeting a student who asked Poletti for academic career advice on following one’s passions rather than mainstream agendas. Poletti’s career strategy, she explains, has been one of “seeing what you get away with”.

Anna Poletti

Perhaps as a counterpoint – undermining expectations that she would talk about zines at Zinedepo -, the lecture focused on three now-canonical woman writers: Virginia Woolf, Audre Lorde and Chris Kraus. Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own (1929) can be read as a feminist tactics manual that prototypes critical tools such as the Bechdel test (whose first nominal appearance was in the 1985 comic strip Dykes to Watch Out For by the American cartoonist Alison Bechdel, and which asks whether in a work of fiction, two women have a meaningful conversation with each other, about a subject other than a man).

Audre Lorde originally wrote her essay The Master Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House in 1984 as a critical reflection on an academic feminist humanities conference that had marginalized lesbians and women of color.5 To add a few words of my own to Poletti’s: In Lorde’s text, “master” obviously refers to slavery and slave holders. It can be read as a critique of both deconstructionist thinking and situationist tactics: a deconstructionist would hold that the master’s tools dismantle themselves, a situationist would try to turn those tools against the master and his house, while Lorde would disagree with both. – In Poletti’s words summarizing Lorde, simple tactics of subversion only allow to temporarily beat the master at his own game, but not change its rules.

Chris Kraus’ 1997 novel I Love Dick can, according to Poletti, be read as an account of women’s forced parasitic economic relation with men, and with each other. Where Wolf compares the vastly different quality of food in Oxford’s men’s and women’s colleges to reflect upon second-class funding and poor conditions of women’s colleges, Kraus gives an update of the parasitic relation between men and women.

Riffing on Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s question “Can the subaltern speak?”, Poletti asks: “Can the parasite write?”6 She suggests to look at “femininity as a parasitic position that must be thought in relation to its host”.

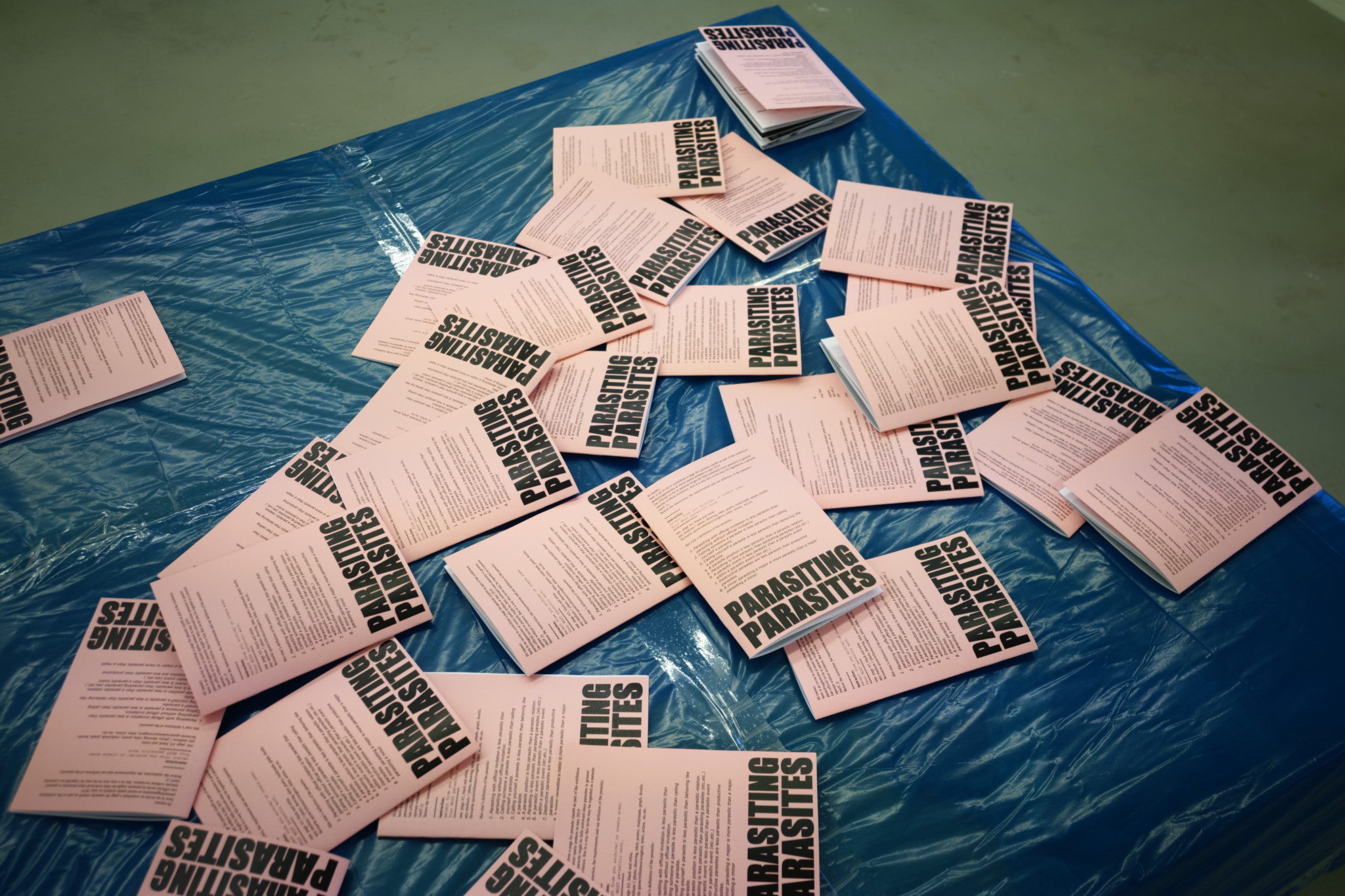

Anna Poletti’s lecture-zine

Poletti’s lecture sparks a lively debate with the audience. One question concerns the ethics of Kraus’ novel (which contains intimate details about the British cultural studies scholar Dick Hebdige, published without his consent). Upon the question whether the parasite was simply a function of suppression and master’s tools, or whether it can be made productive, Poletti replies that there can be enjoyment in frustrating host culture – for example, by not reading recognized literature in a literature department.

Another question concerns the master’s tool as being central to almost any countercultural and critical publishing strategy: The Xerox machine with which most zines are produced happens to be a master’s tool, the Internet is a master’s tool as well. Here, Poletti objects that she did not literally speak of tools, but of practices and patriarchy. Lorde called upon for a new way of scholarly thinking, instead of continuing old modes of discourse.

Wilfried Hou Je Bek, Parasite Game

Prior to having the audience play a computer game that applies game theory to finance – with system collapse as the inevitable outcome -, Wilfried Hou Je Bek gives an introduction into systems, organization and the theory of the “invisible hand”, coined by the philosopher and intellectual founder of liberalism, Adam Smith, in his 1776 book The Wealth of Nations. He proposes to look at the parasitic through the lens of game theory. Here, Hou Je Bek insists that Burroughs had it wrong and that language is not a parasite, but a replicator.

Marc van Elburg & Wilfried Hou Je Bek

According to Hou Je Bek, the question of organization has been central to visual art and music: for example, in the organization of modern -isms around common terms. The cases of André Breton, Valerie Solanas and Andy Warhol, John Lennon and his fan, Abba divorcing, however show that artists are bad at organizing themselves.

For Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the central dilemma of society is the balancing of collective versus individual interest. Examples include the collective hunting of a deer versus individuals hunting rabbits. The former is more efficient, but the short-term gains of the latter will always be preferred to the long-term advantages of the former. This directly translates into game theory.

Adam Smith’s ‘invisible hand’ was a rather obscure concept within his work until it became singled out and highlighted by the 20th century neoliberal ‘Austrian economists’ – most notably Friedrich Hayek [and Ludwig von Mises] who advocated an uninterrupted free market without outside (i.e. state) interference. In reality, however, the invisible hand should be seen as a magic device. It is not clear where it came from. It suggests an equilibrium through the actions of perfectly rational, self-interested actors balancing out each other.

In real life, however, George Orwell’s observation is more accurate: “The trouble with competitions is that somebody wins them”. Or, in other words: The efficient market hypothesis only makes sense when you are in the right position.

The equilibrium theory of the invisible hand seems to leave no room for parasitic actors. This also includes the game theory of the Nobel Prize-winning economist John Forbes Nash Jr.. Margret Thatcher’s famous quote that “there’s no such thing as society” is derived from it: there is no society, only egoistic actors. This theory solves the free-rider problem [a classic concern of economic theories] through making everyone a parasite.

To put these observations into practice, Hou Je Bek programmed a small multiplayer browser game called Parasite Game. In this economic simulation, players can choose to be either contributors or parasites. Parasites will always win more money than contributors, but the game ends when everyone acts as a parasite. Wins accumulate so that in the end, wealth will be unevenly distributed.

In this game, there are two ways of being parasitic: out of strength or out of hopelessness. If everyone contributes, the game ends after 40 rounds; with a certain but limited amount of parasites, the game will last longer. This is an empirical proof of the parasite being beneficial to the system as a whole.

From this game-theoretical approach to free-market liberalism, the following conclusion can be drawn: while artists may not be good at organizing themselves, free-marketeers aren’t either. Hou Je Bek suggests that the function of art should be to develop new ideas of how to organize ourselves. Art could be a laboratory and source of new ideas for game-theoretical solutions. Take, for example, the mass extinction of species: why does it not happen in indigenous communities? Because unlike Thatcher, they have societies.

1. Serres, Michel. The Parasite. University of Minnesota Press, 2007. 10.↩

2. Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature. University of Minnesota Press, 2016.↩

3. Žižek, Slavoj. In Defense of Lost Causes. Verso Books, 2017.↩

4. With his ‘Red Queen hypothesis’ in Van Valen, Leigh. “A new evolutionary law.” Evol Theory 1 (1973): 1-30.↩

5. Lorde, Audre. The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House. Penguin UK, 2018.↩

6. Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. “Can the subaltern speak?.” Rosalind Morris (ed.), Can the subaltern speak? Reflections on the history of an idea (1988): 21-78.↩