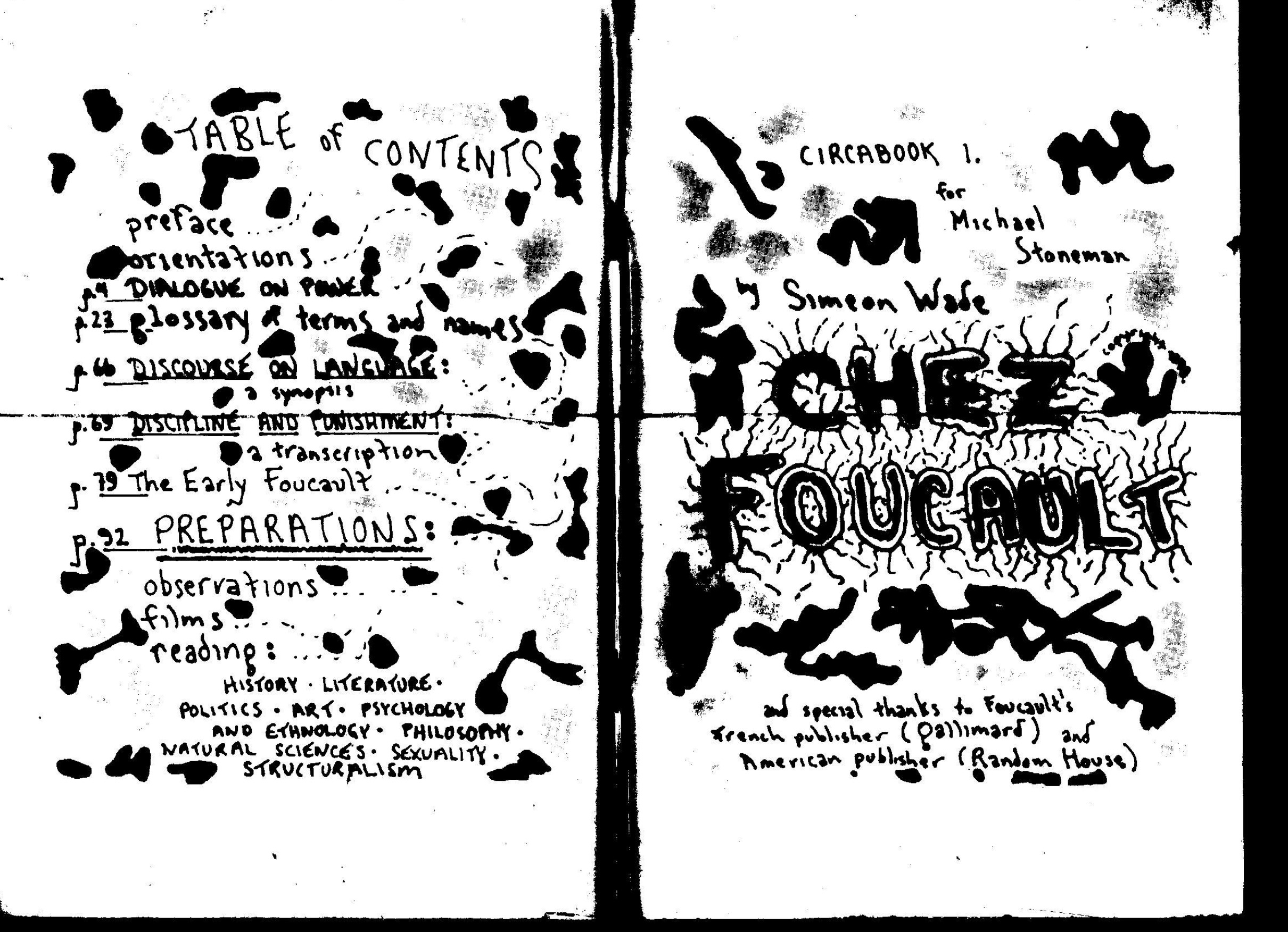

Chez Foucault zine (1978), prepared by Simeon Wade.

Can there be such a thing as an “academic zine”? The very expression sounds like an oxymoron: whereas the academic qualifier came to suggest a hierarchical power structure; a linear, waterfall-like knowledge production process, an indifference towards the way in which form shapes content and can be content, or, more precisely, the standardization and crystallization of its form; the concept of the zine brings to mind anti-authoritarian, grassroots modes of knowledge production and transmission, the lack of a central authority, the dilution of authorship, the eulogy of autonomy, the suspicion towards a strictly efficientist reason. What can ‘the journal’ or ‘the paper’ learn from ‘the zine’?

Before answering this question is maybe good to point out that the unwieldiness of academic publishing isn’t necessarily part of its essence. It might be more of a result of its bureaucratization: after all, methods like the peer-review, are based on a horizontal idea of peers, where who is in possession of a higher symbolic capital is, or should be considered nothing more than a primus inter pares. If this is the case, we can already point out to something that the academic can learn from the zine-maker: de-bureaucratizing. Making sure that the Organization doesn’t stifle knowledge production, manipulation and transmission.

Judy fanzine, dedicated to Judith Butler (1993).

At the same time, however, we should make sure we aren’t idealizing zines. Is the zine medium still a bulwark against cultural gatekeeping? Hard to say. First of all, what was the natural domain of zine-making, that is, subculture, is now in the field of vision of cultural studies, design theory, fashion studies, etc. On the other hand, zines have always played a role in spreading and popularising academic writing; think of Deleuze and Guattari, Michel Foucault (http://www.openculture.com/2015/03/chez-foucault.html) and more recently Judith Butler (https://progressivegeographies.com/2015/02/27/judy-the-1993-judith-butler-fanzine/).

The zine is generally associated with a certain do-it-yourself visual style, deriving from its democratizing ethos. A notorious example of that is Tony Moon’s illustration on Sideburn #1, which was a drawing of three guitar chords which says, “now form a band”. Zine were made and replicated with the Xerox or the Mimeograph, both tools that didn’t require any master. Today, almost three decades after the desktop publishing revolution, after the crumbling of the veneer of disintermediation offered by the web, what is left of the zine-making sovereign impetus? Is the aim of contemporary zines to highlight the jurisdictional/political grey zones of knowledge production (e.g. copyright, authorship, accessibility, etc.). Can a paper downloaded from Sci-Hub be considered a zine?

Judy fanzine, dedicated to Judith Butler (1993).

Another aspect to take into account is the current status of DIY aesthetics: is that just a nostalgic signifier of pre-screen life? Is cut and paste style tactical in any way? Or is it just part of an immobilizing retromania? To a certain extent, zine-making has been turned into a service: not so much something that is done with a certain continuity by a group of peers, but an event that often takes place within some kind of spectacular framework: a media festival, a book fair, a conference. Here we see zine-making not as a way to work or rework content, but itself as the content. This is how we stumble into another oxymoron: “the zine-making workshop”. Sure, zine-making needs some basic equipment, some time to devote to it, but surely not someone who tells you how it should be done. So the zine-maker might end up learning something from the academic: that their activity can be steady, that is not just a gesture performed in front of an audience, that what is written in a zine matters as much as how it is visually structured.