This is the second part of an interview on serial media with Ryan Engley, Professor of Media Studies at Pomona College and one-half of the ‘Why Theory’ podcast.

In Part One we talked about the basics of seriality and Serial Theory, its connections to psychoanalysis, the centrality of ‘the gap’, and how streamed TV and binge watching fits into all this. This week we continue on the topic of serial media, discussing seriality in journalism, the wildly successful podcast ‘Serial’, and the mislead general sentiments towards Netflix’s algorithms and offerings.

Without a doubt, serial media is ubiquitous in our everyday lives – particularly becoming a common therapy during the ongoing pandemic. In an essay on the extremely popular podcast Serial, you argue that the ethics that Serial suggests has its basis in the ethics of desire inextricably bound to its structure. An ethics separate to that of prior journalism and documentary models. Can you explain what is meant by this?

Right, okay. My argument about Serial—and this is importantly and narrowly confined strictly to the show’s first season (I’ll talk about why in a second)—is that it actually stages the process of how a journalist takes a role in her own story.

What Koenig explores is her own desire in the case and this unfolds and becomes manifest serially, through the gaps of the podcast’s construction. This is almost exactly what journalist ethics watchdogs took issue with, however. Critics said that Sarah Koenig was too involved. Also, even though she was too involved, she was unaware of her white privilege while she traipsed through communities of color. I think she admits to some of this now but what’s unfortunate is that they have never done a season like this since.

Serial season one dramatizes how a reporter is confronted with her own desire. This unfolds because the season was aired as episodes were made, leaving no time for her to ‘edit her desire out.

Season two is about Bowe Bergdahl and whether he deserted the U.S. Military or attempted to raise a wider awareness to the U.S. Military’s institutional dysfunction (spoiler: two or so years after the second season, he admitted in military court that he deserted). The third season is radically episodic—each episode has Koenig going over the details of a single case in the Cleveland, Ohio judicial system.

While that third season is certainly a ‘series of connected stories’ it completely lacks the serialized aspect of the first season. The reason why Serial season one works is because of Koenig’s relationship to Adnan and it is clear that they have constantly avoided a repeat of that dynamic in future seasons. In season one, Koenig talks constantly about how she feels like she knows him (there’s that privilege again!) and he constantly reminds her that she doesn’t. He asks her explicitly at one point, ‘What do you want?’ and he calls her both his savior and his executioner (I’m thinking off the top of my head, so may not have the correct quotation). That’s the great question of the first season: what does Sarah Koenig want? I think she tries to convince herself that she wants ‘justice,’ but the rupture of that season occurs because her desire—her clear impartial investment in Adnan—is laid bare for all to see. This is a profoundly psychoanalytic question: what does the other want from me? This happens all the time. What does my friend want from me with this question she’s just asked? I know the server is asking if my meal tasted good but what is he really asking?

He asks her explicitly at one point, ‘What do you want?’… This is a profoundly psychoanalytic question: what does the other want from me?

Lacan phrases this as not understanding ‘what object we are for the other.’ Meaning, we don’t know what other people ‘want from us’ all the time. (Even now, I have no idea if these answers are what you—Jess Henderson—were looking for, or if they are too long, or just deficient in some way!) So Serial season one dramatizes how a reporter is confronted with her own desire. This unfolds because the season was aired as episodes were made, leaving no time for her to ‘edit her desire out.’ They pursued leads that came to them ‘live’—over the course of the season’s publishing—and the whole work feels ‘open’ in a way that the later seasons feel closed.

Journalism in America has been described as ‘in crisis,’ beyond restoration to the practice of journalism exercised for the past 50 years. Does the series present a new way forward, and what impact does this have on the public? Is there a relationship between seriality and the perception of truth?

I think I answer this a little in the previous question but Gabe London, filmmaker-in-residence at Harvard, has written an excellent recent article about the power seriality has to capture truth and its potential political uses (full disclosure: he cites my Serial essay)[1]. I think the series refused to move forward with what it opened up in season one, but I think people, in general, are crying out for American news journalists to have more personal investment in the state of the world.

There are many who do, I want to be clear. There was a great article by FAIR, Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting, that talked about how mainstream American press is very comfortable railing against ‘cancel culture’ when conservatives ‘lose their platform’ or resign (see: The New York Times’ James Benet and Bari Weiss), but they rarely talk about journalists who are fired—canceled—for airing views critical of the right that go off-book, nor do they talk openly or ardently about the Trump administration’s attempt to suppress the release of material critical of him (John Bolton’s book) or, recently, ICE.[2] The air of professional neutrality The New York Times tries to affect comes off more and more as cynical indifference. It’s happened many times during Trump’s presidency, but when he has been questioned by the reporters from other countries, he is hounded about things he has said and I always see on social media people saying, ‘Why don’t American journalists do this?’[3]

The air of professional neutrality The New York Times tries to affect comes off more and more as cynical indifference.

For whatever reason, journalists employed by allegedly ‘liberal’ newspapers value more being seen as politically neutral than to be castigated by tendentious conservatives as actually holding nominally left views. But we have a big, big problem in the American news media with critiquing capitalism. Trump can be written about consistently as a symptom of regressive conservativism but he cannot be rightly seen as the logical conclusion of fetishizing American business and elevating capital to level of politics as such.

Have you explored the role and implications of the algorithm and serial media? What is there to be said on this?

Ed Finn has a great book on algorithms titled What Algorithms Want and, while his approach is not psychoanalytic, I just think he nails what is at stake with algorithms in the popular imagination.

At places like Facebook, Apple, Google and the like, the algorithm they employ (Google’s is called PageRank) is so complicated that there is no single person who knows how it works or why all of it works the way that it does. Engineers are employed to work on, maintenance, and develop just portions of an algorithm.

Apple had an interesting rollout of its Apple credit card that included a mini-scandal of women with better credit histories than men being either denied a credit line or being issued much smaller lines of credit than their less qualified men. One of the high-profile people this affected was Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak and his wife.[4] Apple assured people that they didn’t know why their algorithm was guilty of gender discrimination and the important thing to recognize here is that this is probably literally true—no one knew why the algorithm behaved this way. I don’t say this to let Apple off the hook. Clearly this is an example of how entrenched misogynist assumptions are ideologically that they could find their way into the supposedly objective data processing of an algorithm. But what I would be keen to emphasize here is that the algorithm is not, as Lacan might say, a ‘subject supposed to know,’ nor are the highly skilled techs and engineers who work on the algorithm.

…What I would be keen to emphasize here is that the algorithm is not, as Lacan might say, a ‘subject supposed to know,’ nor are the highly skilled techs and engineers who work on the algorithm.

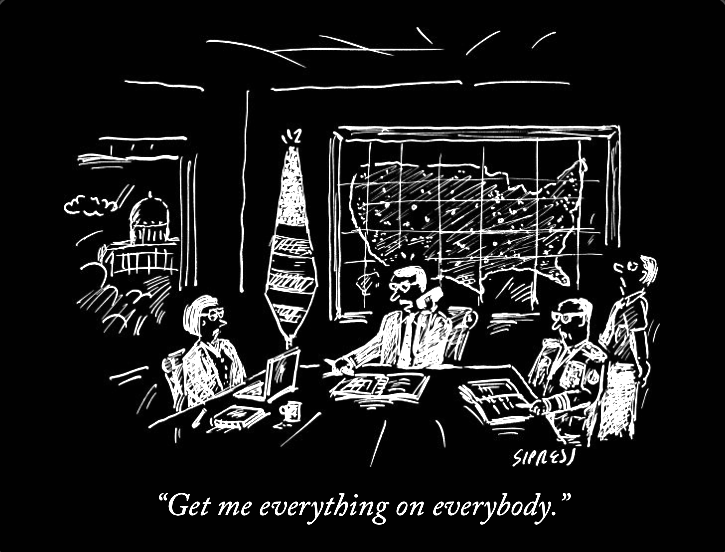

What the phrase ‘there is no subject supposed to know’ means is that there is no person or entity that can guarantee the consistency of your subjectivity. Lacan discussed this when talking about the end of analysis, where the analysand has to move beyond thinking that the analyst has special access to their psyche (believing that, Lacan reasoned, installs a buffer between the analysand and the analytic cure where the analysand never had to confront themselves and their unconscious). Translated more helpfully for the present topic, what the phrase means is that algorithms do not know everything. I’ll often hear people say things like, ‘I was just talking about buying something to a friend and then I saw ads for it on Instagram. Do you think they’re listening? How messed up is that? They know everything, etc.’ and my attitude here is that if you can notice the algorithm working then it is not doing its job. This was more or less my point in an essay I wrote called “Love and Surveillance”: no matter how scary suspicionless domestic spying regimes are (like the NSA in the United States), remember that if they knew anything at all you would not be aware of the work they were doing.

My attitude here is that if you can notice the algorithm working then it is not doing its job.

Again, this doesn’t mean—in an American context—that we should not work to overturn The Patriot Act because “they don’t really know anything anyway,” it just means that believing in the total authority of the algorithm as this fixed point of meaning is a paranoid fantasy. When one imagines the creation of algorithmic content as this perfect totality, one misses the actual points of break and torsion that allow for resistance to take place.

I write all this as setup to my actual answer to your question. I love the first diegetic exchange in Netflix’s Maniac (2018) because it is a meta-reflexive nod toward the things that people think about Netflix original programming: that they are constantly mining user habits for data and that they are using an algorithm to green light shows and pretty soon we won’t even know what we want anymore because Netflix will already know.

After an intro sequence, Maniac begins with a store clerk urging Emma Stone’s character not to buy cigarettes with an ‘Ad Buddy,’ a physical person who asks questions to mine you for data. The clerk says that ‘they’ (always a paranoid ‘they’) maintain a ‘national database of desires’ and that they know what you want before you do and that it’s scary stuff.

Martin Scorsese expressed this very same view recently, saying that Netflix’s algorithm ‘takes away creative viewing.’[5] This is always the attitude: the algorithm is taking something away from us. The least sympathetic reading of Scorsese’s comments is that Netflix is taking away ‘choice.’ Choice is the highest of liberal capitalist ideals and it is always sold as being equivalent to freedom when it never is. The more sympathetic reading of Scorsese’s comment is that the algorithm takes away spontaneity and the delight of discovery. Possibly, but I think this is another fantasy. People have always relied on critics, reviews, viewing guides, IMDb ratings, the Academy Awards, the American Film Institute Top 100 Films, etc. to help them comb through the large body of production that is Film. I don’t think books such as 1000 Films to See Before You Die are ‘taking something away’ from me. A guide can be useful, of course.

One of my favorite things to do as a kid was to walk the aisles in a Blockbuster to pick out a movie for my family’s Friday Night Movie Night. That felt like a total bodily exploration of film, in the sense that I was physically wandering aisles in the way that I scroll through menus now. Except…I was limited by what my local Blockbuster stocked, wasn’t I?

Martin Scorsese Says Streaming Algorithms—Including Netflix’s—Are Ruining Audiences

The filmmaker admitted he’s as susceptible as anyone to an algorithm—but encouraged moviegoers to seek out more titles on their own.Martin Scorsese Is Begging You Not to Watch The Irishman on Your Phone

However, he will accept “a big iPad, maybe.”

Obviously, what Scorsese and others are worried about is that choices are predetermined for you with an algorithm, that your imagination and exploration of film is artificially narrowed down. But…don’t all the other resources I mentioned do their own version of narrowing down and compromising a supposedly free kind of exploration? One of my favorite things to do as a kid was to walk the aisles in a Blockbuster to pick out a movie for my family’s Friday Night Movie Night. That felt like a total bodily exploration of film, in the sense that I was physically wandering aisles in the way that I scroll through menus now. Except…I was limited by what my local Blockbuster stocked, wasn’t I? Further, it’s really only been until recently that there has been a widespread pushback against how institutions like the Academy really only award certain kinds of films (i.e. #OscarsSoWhite).

People complaining about how bad the Netflix algorithm is at recommending things to them. This, to me, is ‘algorithmic freedom’… The goal is to celebrate this moment where a company—in this case the first streaming giant—has demonstrably failed in one of its most basic tasks.

If there is inquiry into the algorithm to be done in terms of a theory of seriality, I would want to insist that it start with the moments of break and failure. If you Google the phrase ‘Netflix algorithm bad’ you will get two types of hits. One will be a kind of artistic/ paranoid panic like in the Scorsese example. The other will be people complaining about how bad the Netflix algorithm is at recommending things to them. This, to me, is ‘algorithmic freedom’: when the thing that supposedly knows you better than you know yourself proves it doesn’t know you at all. The goal here shouldn’t be to sit back, complain on Reddit, and wait for Netflix to make their algorithm so good that you don’t ever have to look for anything ever again. The goal is to celebrate this moment where a company—in this case the first streaming giant—has demonstrably failed in one of its most basic tasks.

If there is inquiry into the algorithm to be done in terms of a theory of seriality, I would want to insist that it start with the moments of break and failure…

If you can see a system’s points of break and its failures, you see that your subjectivity is not under the thumb of a perfect system.

Something else Scorsese says in that Vanity Fair piece is worth pushing back on because it constitutes part of a popular myth that is worth getting into: the idea that ‘You can watch anything—anytime, anywhere.’ This is damagingly untrue. I’m not sure what it looks like today, but at one point in 2018, Netflix carried only ‘two [streaming] titles made before 1930 . . . they offer only 15 films made before 1950, 26 made before 1970, and 98 made before 1990.’[6] Thinking that Netflix carries ‘everything’ or that it has only lost The Office (US) makes us terrible stewards of film, television, and media history. All of this tracks back to believing in the totality and infallibility of the algorithm.

Something else Scorsese says… constitutes part of a popular myth that is worth getting into: the idea that ‘You can watch anything—anytime, anywhere.’

This is damagingly untrue.

If one reads the success of algorithmic culture as total, then you misrecognize the ‘everything’ that Netflix offers in a way that benefits them. If you believe that you can watch anything streaming, then you’ve allowed corporations to narrow down the amount of art that has ever been created even before an algorithm narrows it down even further. If, however, you can see a system’s points of break and its failures, you see that your subjectivity is not under the thumb of a perfect system. Embracing and interrogating these gaps and fissures gives rise to more pointed media and political critique, which to me is nothing less than the full exercising of creativity.

Embracing and interrogating these gaps and fissures gives rise to more pointed media and political critique, which to me is nothing less than the full exercising of creativity.

Besides journalism, what other areas are developing with seriality? Are there new forms of the series that you have you seen and been excited by?

I think there is a lot of work to be done in understanding the social through the serial but, in terms of narrative media, I’m intrigued by what videogames might be able to offer. Obviously, videogames have had ‘sequels’ since Super Mario Bros. but the way patches and DLC are used to fundamentally change the state of videogame worlds long after initial release[7] has the potential to serve as a new medium specific way of imagining the serial form.

I’m also a little interested in ‘non-narrative’ seriality, such as iPhone updates. The reason is that, even though an iPhone update comes with a dispassionate description of updates and bug fixes it nonetheless tells a ‘story’ of ‘what went wrong’ and what features that, at one point in time seemed totally sufficient, later became insufficient and broken. They end up being indexes of obsolescence that, again, have a narrative to them. They tell you where an industry was, where it went to, what kind of unexpected twists and turns occurred, and—when you start thinking that way—what previously seemed like perfunctory legalese starts to have acquire the meta-structure of a Dickensian serial.

One last question, what’s the difference in forms of seriality between shows that one can watch any episode and ‘get it’ vs. shows with an ongoing narrative that are difficult to enjoyable jump into any episode on? I’m thinking about The Simpsons vs. Groening’s newer Disenchantment series. The former comes from trad TV, and the latter released as entire series on streamed TV, with a narrative arch one can be enticed to bingeably watch. I guess the query is about both narrative in binging and streamed tv, and what seriality means to each type?

This links back to our discussion on the gap earlier. I think the task is to locate the serial gap and what it does differently relative to the content you are looking at. The temporal gap of traditional serial media has a more celebrated creative and critical function, but just because Netflix series’ lack this weekly interruption does not mean Netflix has actually achieved ‘gapless’ seriality.

As I argue in my book, Netflix’s various attempts to erase the gaps in traditionally released television series actually makes them more apparent. When I binge watch a series on DVD, I never notice the opening credits or intro sequence of a show; after enough episodes, they just pass me by. Netflix, however, is constantly asking me if I want to skip stuff. Even if they found a way to remove these hallmarks of traditional TV interruptions (such as ad breaks), they cannot erase the way the serial form affecting the construction of the series, which is what Freud discovered when he binge-read Daniel Deronda.

Netflix’s various attempts to erase the gaps in traditionally released television series actually makes them more apparent.

Now, when it comes to Netflix original programming, the gaps articulate differently. My favorite example is the most hated episode of Stranger Things, possibly Netflix’s most popular scripted show. The episode in question is called ‘The Lost Sister’ and, without going into the details of the show or what happened in that episode, what Stranger Things did was place an entire episode full of action, answers, and intrigue that seemed totally disconnected to the episodes that fall on either side of it.

The episode before ‘The Lost Sister’ ends on a mid-season cliffhanger. ‘The Lost Sister’ does not pick up this action, it tells a semi-related story about a character who has been largely absent for much of the season up until that point. What you’ll see in the IMDb ratings of this episode is the recommendation to ‘skip it.’ Just to pull the point together: what Stranger Things managed to do was to create an episode that was, for all intents and purposes, ‘a serial gap.’ In other words, they released a gap that was filled with content. Other Netflix series do this but receive far less vitriol for it.

In fact, the idea of an installment not picking up the action of a cliffhanger is not even new, but—within the context of Netflix’s ‘all at once’ binge narrative model—it feels something like a betrayal. The point of Netflix series is that they are not like traditional TV. The episodes have variable length (like Lacan’s analytic sessions!), they don’t have mandated commercial or act breaks, and they can tell whatever kind of story the creator wants (this is the popular myth embraced by viewers and put out by Netflix).

Netflix, in other words, tries to bill itself as the ‘solution’ to the problem of traditional narrative seriality. And yet, their narrative model makes people antsier and more impatient when it seems like they’ve released a ‘filler’ episode. This goes back to the ‘ten-hour movie’ problem. TV shows have down time. They often take a breath. If a series was all-action all-the-time, none of its action would mean anything. This ends up being the narrative function of the commercial break: it gives an external limit that helps lend individual episodes of a TV series shape and cohesion.

TV shows have down time. They often take a breath. If a series was all-action all-the-time, none of its action would mean anything. This ends up being the narrative function of the commercial break.

Netflix (and this is true of all streaming companies, but Netflix is just the first and most famous example), in eschewing traditional breaks, just invents new places for them. They are either the yearlong breaks between seasons, or they are self-instituted breaks between episodes or within episodes. Or, in the wild attempt to maintain narrative continuity, you get a device break. I know I’m not alone in watching something first on my television and then going to bed but, oh, I don’t know, maybe I’m not tired and one more episode? So, I’ll put the next episode on my computer. Maybe I’ll start the next episode the next day on my computer but, as I leave for work, I’ll watch it on my phone and I’ll pause at the moments when I realize oh, right, I’m a pedestrian right now and not the only person in the universe. I should look both ways for traffic.

In short, the attempt to eliminate breaks just puts them somewhere else. I don’t think the publishing schedule/traditional temporal breaks of older media are more special or more interesting than what streaming series have created—especially since it seems to be against their intention.

Thank you Ryan. I am taken by your work on the serial and look forward to the release of your book–whichever title you land on. To be continued…

Part One of the interview with Ryan Engley can be found here.

[1] https://shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/London-Serial-Narratives-March-2020.pdf

[2] https://fair.org/home/medias-cancel-culture-debate-obscures-direct-threats-to-first-amendment/

[3] This is so funny but I wrote this sentence yesterday and today this happened: https://www.reddit.com/r/worldnews/comments/i3ghz9/australian_reporter_jonathan_swan_corners_donald/

[4] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-goldman-sachs-apple/apple-co-founder-says-apple-card-algorithm-gave-wife-lower-credit-limit-idUSKBN1XL038

[5] https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2020/01/martin-scorsese-streaming-algorithms-moviegoers

[6] This data is from Kate Hagen’s excellent essay “In Search of the Last Great Video Store.” https://blog.blcklst.com/in-search-of-the-last-great-video-store-efcc393f2982

[7] No Man’s Sky and Final Fantasy XIV are the oft cited examples for console gaming but mobile games like Two Dots are important to think about here, as well.