In recent times, conversations I’m having with fellow art workers tend to spiral into fantasies of escaping the art institutions. A far-right government has taken power in the Netherlands a few months ago, and everyone expects a crackdown on counter-hegemonic culture. In anticipation of the blows to come, cultural institutions have already started self-censoring and repressing, for instance, pro-Palestine organizing. This fits into a general image of institutions prioritizing their continued existence over any other value (no matter the ubiquity of ‘ecological awareness’, ‘diversity’, ‘fair practice’, and other social justice buzzwords in their policy plans and public statements). Is it time to abandon the ship?

Maybe not. Let us, for a second, call to mind the alternative: a world without art institutions. This doom scenario is, as often, already taking material shape in the US. A progressive-entrepreneurial vanguard of ‘post-internet’ artists like Brad Troemel and Joshua Citarella has engaged with the emergence of Web3 technology, financialization of art and social relations, the growing desire for community feedback and learning in societies atomized by social media, and a belief that legacy-art institutions are stuck. Witnessing the decline of public institutions (or ‘the public’ in general), they initiated a pivot from artist to ‘content creator’, making paywalled video essays, newsletters, podcasts, and selling cheap multiples that blur the boundary between art and merch. They are marketing their Discord servers as online clubhouses that replace the meatspace underground scene as well as traditional learning institutions. This is the already existing reality of a post-institutional art world: a carefully curated and walled off, ‘relevant’, innovative pay-to-win pirate colony in the open sea of platform capitalism.

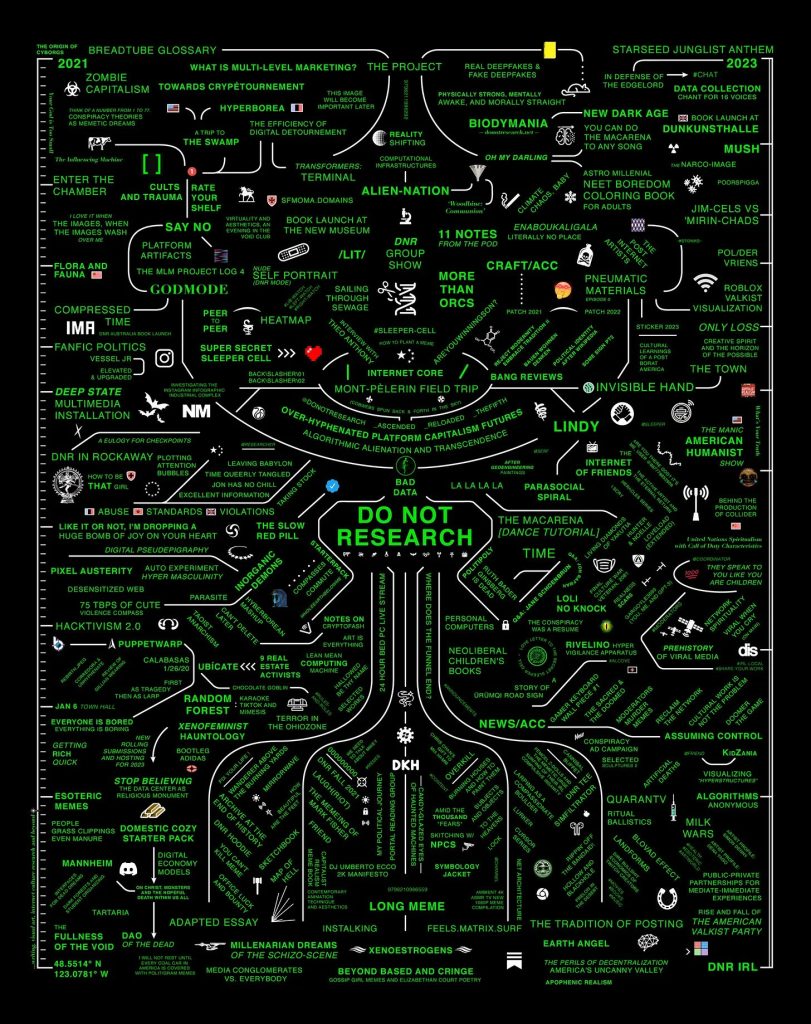

The most prominent among these subscription services is Joshua Citarella’s Do Not Research. DNR is a platform for writing, visual art, and internet culture research. It’s main outlet is a Substack newsletter, but paying members also get access to a lively Discord server which is considered by insiders as the ‘counter-institution’ built by the post-institutional art scene.

We owe the notion of ‘post-institutional art’ to Ben Davis, an influential, Marxist American art critic, who coined the term in a conversation with Citarella on the podcast of Artnet News, where Davis works. I don’t hate his provocation. It is obvious that we have to think outside of the norms that most art institutions operate in. But let’s be careful what we wish for. Before long, post-institutional art discourse can turn from a speculative trend forecast into a self-fulfilling prophecy. In the same conversation, Citarella made clear that he would happily sell his curatorial consultations to (public) art institutions looking to be saved from drowning in digital information overload. ‘Post-institutional’ should therefore be understood as a demand for a systemic transformation rather than a real abandonment of the institutions.

Citarella’s ‘disruptor’ narrative neatly follows the script established by creative industry ventures over the past 30 years, rejuvenating and consolidating an existing industry with ‘radical innovations’. Definitely, the figure of the art theory influencer is genuinely new and seems to work for a few people (the Berlin-based podcast New Models should be mentioned here as well). Taking elements from the archetypes of the artist, the theorist, the ideologue, the influencer, the curator, and the consultant, a few people have carved out a niche for themselves in the grey areas around the institutions of art, cultural industries, digital media, and finance – which is, in fact, the heartland of the creative industries, not entirely institutional, but not independent either. But let’s not forget that, as Silvio Lorusso nicely put it to me: ‘We can’t open a Patreon for everything’. Patreonization of culture is boring, politically detached, and, most importantly, it doesn’t work. The postironic, total surrender to the market of post-institutional art is therefore pretty bleak. It offers a new vibe, but no new model.

Sure, we need networking and self-organizing, we need to transform social and technical infrastructures and social ones. But not to have a walled-off garden. We need this to make a claim to defend the common good. We cannot afford to forget about the long march through the institutions. It’s an uphill battle, but necessary and ultimately much more effective. I hope that one comparative example is enough to show what I mean.

Ahmet Öğüt, Bakunin’s Barricade, 2015–2020, installed at Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam.

Recently, I was part of a collective that requested the Stedelijk Museum to loan out Ahmet Öğüt’s work Bakunin’s Barricade to protect pro-Palestinian student encampments in Amsterdam against police violence. You can read a longer version of the story here, but, basically, the museum refused to put works in its collection at risk to further social justice. Bakunin’s Barricade became a monument to opportunities missed, and a perfect example of the aestheticization of politics in art institutions. Expected? Maybe. Unavoidable? Not so much.

In 2011, the Van Abbemuseum and the International Art Academy Palestine co-produced Picasso in Palestine, the exhibition of a Picasso painting from the collection of the Van Abbe Museum in Ramallah, Palestine. The operation of bringing the cubist painting Buste de Femme from 1943, with an insurance value of about 1 million euros at the time, into a country not recognized by Dutch law, confronted, and pushed through many faltering infrastructures: from difficulties finding insurance and the absence of a climate-controlled exhibition space, to the clash between the modernist universalism represented in Picasso and the repression of the Israeli apartheid regime. Even when each of these issues was accounted for, the minivan with the artwork and its handlers in it had to cross the no-man’s land between Israel and Palestine with no other protection than the cultural and monetary value of Buste de Femme. Willingly, the Van Abbemuseum staked the value of one of the most important pieces of its collection for the sake of social justice. The International Art Academy Palestine and Van Abbemuseum achieved something the Stedelijk, with its talk of ‘platforms’ for ‘institutional critique’ could have never done. Today, Picasso in Palestine lives on as a monument to the possibility of art institutions creating material change.

Khaled Hourani, Picasso in Palestine, 2019.

The difference between these two institutions is plain and simple: one accepts the call to political commitment, and the other refuses it. This should, I believe, be the real focus point of debates on the ‘art institutional question’. (This is not, or at least not only, a matter of public funding. Both the Stedelijk and the Van Abbe get public funding, and both can lose it.) How to embark on a contemporary, renewed attempt to align the institutional forces of art production with the Left, with international solidarity, and with decolonization – which includes the push for workers’ emancipation and economic sustainability, and politicized speculations with value-production? For all their problems and complexities, we need a network of infrastructurally critical institutions, patainstitutions, and initiatives. A post-institutional art world is not the way to go.