I write to you from an island in the far south of the southern hemisphere to share an account of events that manifested around The Unconformity, a festival that never happened. Cancelled 1 hour before the formal opening. The industrial space of Queenstown is charged. I was fortunate to attend the vernissage to recount a sliver of cultural activities from the antipodes. In the grip of hells gates a damaged butterfly wing is not perceived as anything but something broken, nor can punk guerrilla girls be anything but vicious criminals or forsaken matriarchs. Matters like these are epitomised as I stand amidst the ruins of this dystopian city overrun by exploitation, amid the pandemic, the rogue drug dealer with the Delta variant and the vast burning tyre inferno at the Mount Lyell mine.

A world in which an inheritress can be a bottom bitch. Descending mobility? Not at all, this is contemporary impartiality, where a choreography may have as many spectators in attendance as dancers, and you may never know the difference. Duplicitous identity politics, and gender divisions as delicate as butterfly wings, provoke semantic transparencies. This is our epoch: a clown becomes a Prime Minister; a hitman becomes a president; the prince becomes a Silicon Valley entrepreneur; a duplicitous hussy laden with affliction climbs the academic ladder. In need of a perceptual shift? Then travel to a different country in order to attain a new life with opportunities and altered constraints to navigate. It’s revitalising (or at least for a while) but eventually all bucolic behaviour softens into the trailblazing mutability of convention.

[I wrote an alternative version of this text for Memory Palace an online journal featuring new critical writing about Tasmanian arts and culture. ]

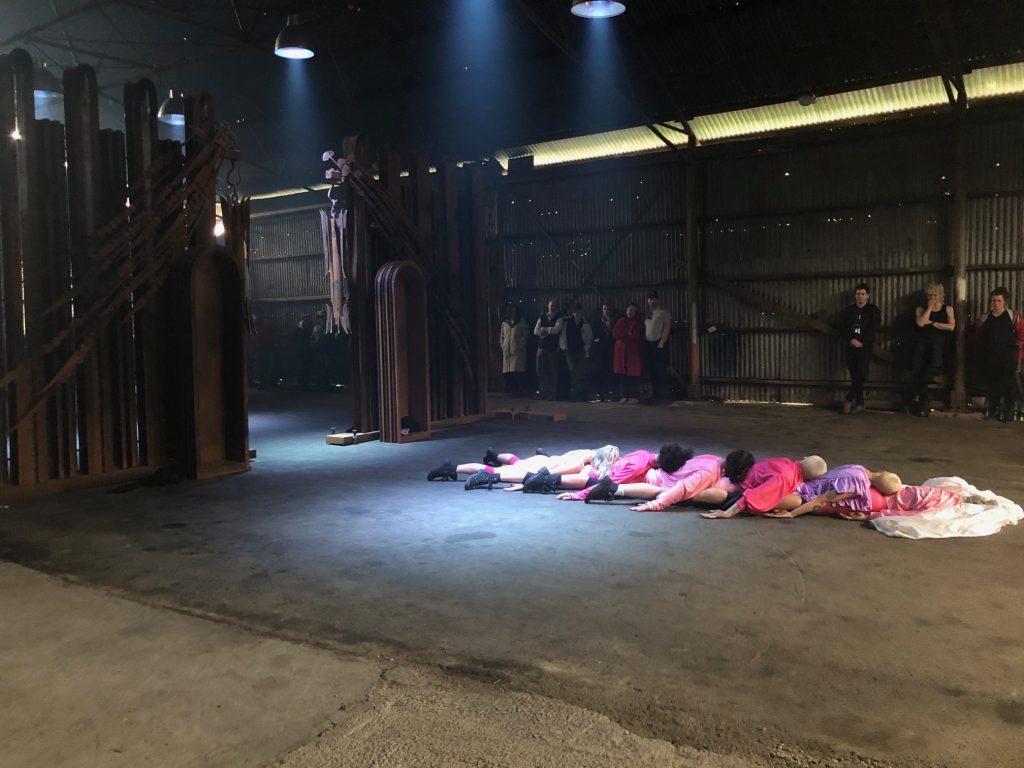

Arriving at Hunter Street Shed, spectators are obliged to check in and verify corporeal location (through QR or by one’s own handwriting). On entering the audience comes to countenance a colossal matrixial metal gateway intricately crafted and forged by blacksmith Pete Mattila. Situated ‘in the round,’ the audience surrounds the performance area. The way in which spectators choose to inhabit the space is observable, as much as the performers (from GUTS Dance, an organisation based in the central Australian desert and Tasdance, the island’s flagship contemporary dance establishment).

The ensemble travels through a crash course in a civilization that accepts the ‘Gates of Hell’ as a relative feature. Transitioning diagonally through the terrestrial gateway, they move through assorted kinetic scores sparked by an individual who initiates a gesticulation which then ricochets through the collective. This reverberates in variations of flocking, gathering, expanding and contracting of gestures. A sudden jolt (either a head flick, or full body ripple) is often a circuit breaker, integrated in the movement score, improvised and corroborated along with various modern dance training modalities and techniques (the deep lunges in Iyengar Yoga is most prominent for those who know the drill). The dancers return to draw out particular phrases that gather momentum, developing throughout the work. They do not aim to create a character with a persona but move straightforwardly to perform actions in space. This minimal tradition of choreography is described by renowned modern dance pioneer Yvonne Rainer as being where “the walker can choose to bump, lightly, into the standing person; that’s ‘jostling,’ and it can free the standing person to get back in motion.”

The costume design by Andrew Treloar is an active intermediary that considerably strengthens the exuberance of work, emphasising the fluidity between the individual and the collective. The dancers’ pastel Lycra outfits with neogothic flourishes are a fitting sobriquet for countenancing a tellurian gateway. The more these components are donned, adorned and shed intermittently by the ensemble, the more an atmosphere of sublimation is aroused – individuals perish, the latent grotesque flows and the outlandish is unbolted. Exploring these capricious transformations, the dancers’ draping themselves (or lack thereof) with the nearest piece of material contributes to motifs of depersonalisation, disintegration, and deformation. The mutable attentiveness to the synthetic costume contrasts to the dancers’ neglect of the two lace wedding gowns strewn on either side of the threshold. Their abandonment of these gowns visually bawls out for attention. Anticipation builds. It is predictable when eventually one of these white dresses baits the contemplation of a dancer. She dons a pair of soccer boots customised with taps, and begins to tap dance upon the frock directly trammelling it into the ground. Ostensibly crushing the bourgeois contract formed in the fatigued ritual of marriage. Next, deserting the dress, the performer veers across the space. The frantic tap dance caricature continues and grows into a bellicose tirade. Smashing her feet against the metal. As she comes into proximity with the gateway. This moment forms the crescendo of the work.

Notably the vaudevillian act of ‘tap dancing’ manifests astonished, even gleeful reactions with the spectator. Tap is an experiential form which allows audience familiarity and affection to come into play. There was an opportunity here to leverage this shared economy of public feeling. Instead, the audience response seemed irrelevant to what evolved. How dance is produced and received is a product of particular cultural and political contexts. For example, nowadays it’s usual that the performance may not occur behind a proscenium arch; yet the majority of contemporary dance choreographers treat the stage as though the pictorial frame is still there. In Collision, there is a clear desire to operate on a more sophisticated level. As the audience entered the space, ushers issued the instruction: “Do not sit down but move freely around the space, but avoid the sculpture in the centre”. It’s plausible that the intention of the choreographer Jo Lloyd was for the audience to be on foot and moving to question traditional hierarchies of knowledge, accountability and control structures. And yet, when I saw the performance, the audience predominantly opted to stay still; perhaps knowing or sensing that the work was not about to incorporate or respond to their genuine interactions within it. Paying more attention to the social contract with the audience, the dramaturgy, may have resolved these matters.

Alluding to the alchemical processes that are essential to both the arts of blacksmithing and dance, Collision overflowed with disintegrated meaning and disfigured instructions, challenging and disturbed the atmosphere. In a place of obliterated infrastructure, this performance amongst and around a gateway signalled to that which is external, a threshold to a location outside all possible measures. The experience evoked an expanded sense of being human in a quest for another world, which may be not merely possible but necessary.

Collision (world premiere) Presented by The Unconformity at the Hunter Street Shed, Queenstown, 14 October 2021

Choreographed by Jo Lloyd, blacksmithing by Pete Mattila. Costume design by Andrew Treloar, music by Duane Morrison, lighting and production by Chris Jackson. Performed by Gabriel Comerford, Jenni Large, Amber McCartney, Kyall Shanks, Madeleine Krenek, Frankie Snowdon. Presented by Tasdance and the GUTS Dance Ensemble.

Works cited

Yvonne Rainer, A Woman Who…Essays, Interviews, Scripts (Baltimore: The John Hopkins University. 2001)

“Collision at the Unconformity.” Tasdance, 31 August 2021, https://www.tasdance.com.au/news/2021/8/31/collision-at-the-unconformity.

“Collisions at Unconformity.” Pete Mattila Studio, https://www.petemattila.com/collaborations.