“The best material model of a cat is another, or preferably the same, cat.”

– Norbert Wiener

Cats hold a strange role in the history of cybernetics. Most iconically, Norbert Wiener, Julian Bigelow, and Arturo Rosenblueth used the example of a cat chasing a mouse to exemplify their account of adaptive behavior and purpose-ness. Stafford Beer also used cats in his drawings as symbols of disturbance and instances of noise. Heinz von Foerster elaborated on Kater Murr, the novel by E. T. A. Hoffmann, as one of his most beloved childhood books. Before everything else there was Schrödinger’s cat. Thus, it might not have been coincidental that at the height of the Cold War, in 1968, the first 40-second-long computer animation in the Soviet Union, led by mathematician Nikolai Konstantinow, was a simulation of a cat’s movements.

Schrödinger’s Cat

Clearly, where there is a (computer-) mouse, there should be a cat. The cat (logically?) entered the cyber-age, proceeding onto the internet. So, we might ask, what, exactly, is it with cats? Books have been written on the internet of cats, published by acclaimed university presses, and even The New York Times is interested in the phenomenon. As for ourselves, we follow a cat-channel on Instagram reels and can view content from thousands of cat Twitter accounts 24/7.

Moreover, contrary to what one might believe, the cat has always been political. It is argued that cat content has a positive impact on internet users, even leading them to engage more with political content as it helps to refocus their concentration in the midst of their news feeds. Cats are also discussed as mediators of political content, as cat GIFs and memes often carry political messages to users who might not be politically active or interested in politics per se.

So we might ask, what is the politics of the internet cat? Is there a politische Zoologie (as we would frame it in academic German) of the internet cat? If not, should one be written?

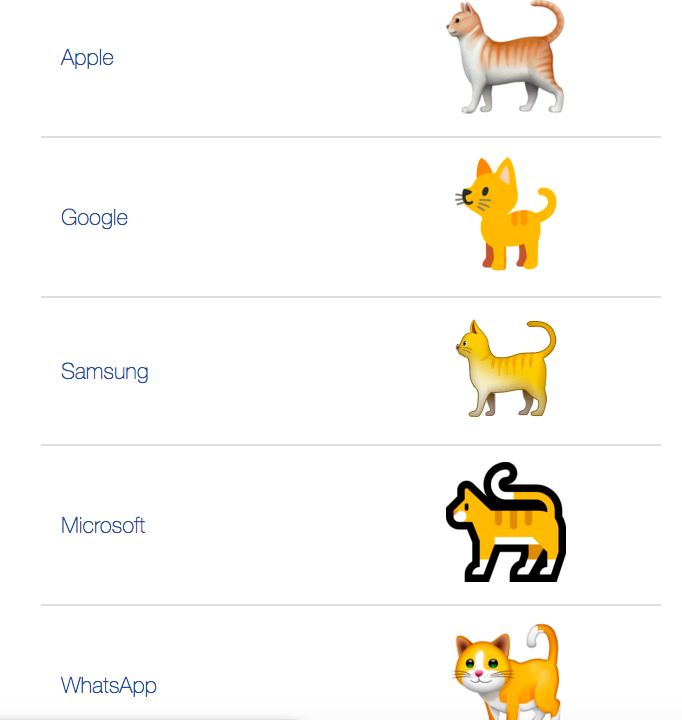

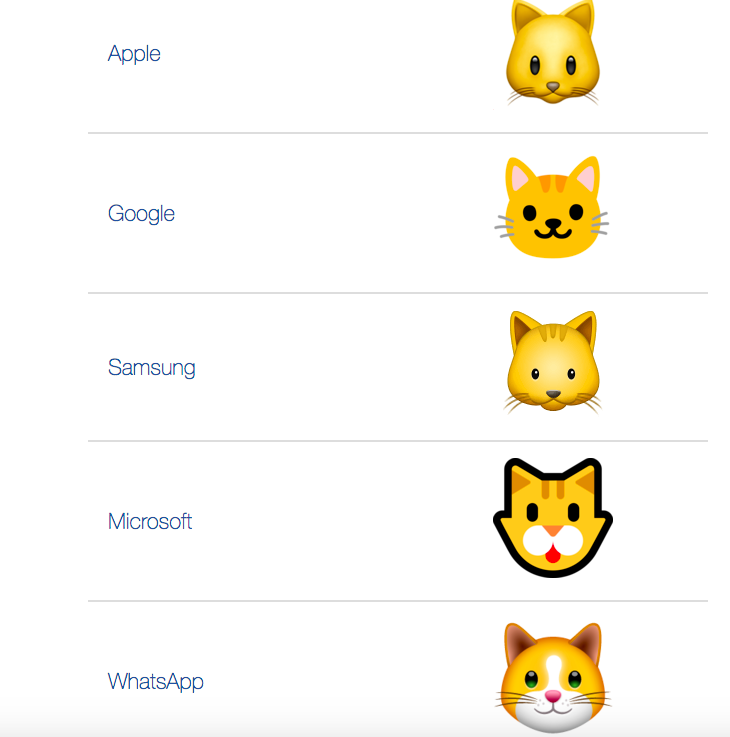

As is the case with any internet icon, each tech company has its own interpretation of the cat:

There’s also various cat faces:

- 😼Cat Face With Wry Smile

- 😹Cat Face With Tears of Joy

- 🙀Weary Cat Face

- 😾Pouting Cat Face

- 😿Crying Cat Face

- 😻Smiling Cat Face With Heart-Eyes

- 😺Grinning Cat Face

- 😸Grinning Cat Face With Smiling Eyes

- 😽Kissing Cat Face

And so on. Depending on the messaging channel or internet company, the cats can have different colors: Google’s cat face was once orange, Samsung’s gray, and Facebook’s gray and white.

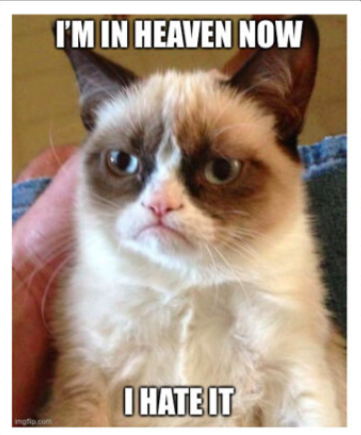

In addition, some cats are luckier than others. Some have achieved iconic status as internet celebrities in the age of infinite reproduction, such as GrumpyCat (which, sadly, died recently) or the Master Cat / The Booted Cat, which is now part of the techno-cultural imaginary. One particular cat that dominated the emergence of the early internet was Frank the Cat. It is almost certain that Frank was the first cat ever posted online; and after him came the “Meowchat,” an online group in which users imitated cat sounds. Subsequently, people posted pictures, or copies rather, of cats sitting on copy machines, which is today recognized as the first act of producing “user-generated content,” without which social media would logically not exist.

The iconic “Grumpy Cat”, which died recently.

Thus, it should not be surprising that there is a wide selection of cute cat images on Facebook. It should also appear almost consequential that we use cat faces as representatives of our own, to express our emotions digitally.

A selection of cute cats on Facebook

Cats even occupy the better side of the digital, e.g., with the Chaos Computer Club having used them in several instances as a symbol for the group’s conferences.

The CCC’s Cat Symbol.

It is well known that cats have a peculiar and quite strong legacy in the history of philosophy, especially in French philosophy and poststructuralism. Levi-Strauss described an act of recognition with a cat before he wrote his Tristes Tropiques. There are also many pictures of Sartre, Foucault, and Derrida with their cats. Derrida even problematized the history of phallogocentrism in Western philosophy while recalling an encounter with his own cat, Logos, while he himself was naked. As Christopher Kinman writes,

Derrida in his book, The Animal That Therefore I Am, discusses the expectation before him to talk about animals, but, instead of “talking about”, and instead of describing animal as a generality, or even as an assortment of species, he describes an incident, a specific moment with a singular and real cat, with his cat, Logos. He described a moment of being naked in the presence of this cat, with the cat looking at him. He described a sense, of discomfort, even shame from this experience of having his naked body gazed upon by his cat. Derrida saw that he was not so much looking as he was being looked at, and not by some global category of “animal”, but by an all-too-present, staring feline.

Derrida continues, always returning to the cat, his cat, the specific cat staring at his naked body. He reminds us that the experience of being looked upon by an animal is almost never the vantage point from which animals are talked about in both science and philosophy. Instead, the gaze is repeatedly and consistently from the human eyes upon the body of the animal. We, the humans (and in particular, we the philosophers, the scientists, and other institutional players) are the observers, and from the position of looking upon the animal we also find ourselves with the privilege of being the ones who name, who examine, and who interpret the animal. The scientific and philosophical eye never expects the animal to be examining the examiner.

Why do we experience such joy when gazing at internet cats 24/7? Is it merely a direct consequence of the cat having an impact on the emergence of the internet and user-generated content, i.e., is it simply logical that the cat, having contributed to the internet is now a big part of it? Or are cat memes merely acts of disturbances, quick announcements of short breaks with the boring, at times catastrophic, sometimes annoying feedback-loops of social media? Are they an expression of our longing at comfort in apocalyptic times? Or is it maybe the fact that the cat in cyberspace is not staring back at us? Is it reassuring for us that they do not leave us with the weird feeling that Derrida experienced in his mystical encounter with Logos? Is it, thus, a way for us to preserve the human anthropocentric view, avoiding the animal’s gaze? Is it enjoyable that the cat is not looking back at us?

Finally, and probably most importantly, cats are found in theories of the digital. However, they are different cats, namely, disappearing cats. Oddly enough, Baudrillard used a very particular cat, one of the most magic and mysterious of all, Cheshire, to illustrate the disappearance of the self in a time of hyperreality. The cat embodies total simulation and the vanishing of the real. Yet, the act of disappearance is not without consequences and effects, as Baudrillard writes:

“At any rate, nothing just vanishes; of everything that disappears there remain traces. The problem is what remains when everything has disappeared. It’s a bit like Lewis Carroll’s Cheshire Cat, whose grin still hovers in the air after the rest of him has vanished. […] Now, a cat’s grin is already something terrifying, but the grin without the cat is even more terrifying…”

He continues:

“Let’s stay with psychology and look a little at the disappearance of the subject, which is, more or less, the mirror image of the disappearance of the real. And in fact the subject––the subject as agency of will, of freedom, of representation, the subject of power, of knowledge, of history––is disappearing, but it leaves its ghost behind, its narcissistic double, more or less as the Cat left its grin hovering.”

To express this in a GIF and to really extend this whole argument into hyper-hyperreality:

So would we want the cat to disappear at all? Or does it exert an “occult influence,” as Baudrillard, asserts for anything that has vanished already—vanished but not vanished at all? What does it mean for a theory of hyperreality that we can express the vanishing of the cat in a meme? Is it a total affirmation of the theory, is it a simulation of simulation, or is it a negation of negation? What comes after the cat’s disappearance? What is a politics of the real in the time of the internet?

Should we consult the cat for a theory of politics in the age of post-politics?