Transcript

Hello everyone, thanks for being here. Today, I’m going to talk about a few ideas related to the “Entreprecariat”, a concept I’ve been trying to articulate for some time now.

I’d like to start by saying something on how this interest came about. Not so long ago, I got a 3 years research scholarship which, among other things, provided me with a certain degree of stability, characterized by a rarely long temporal horizon. Despites being an obvious exception, my relative stability felt normal to me, and from this vantage point I could perceive all the “short intention spans” of my friends and colleagues as a structural aberration.

All of this changed when the scholarship was coming to an end. This is when I felt the full weight of reality all at once.

From now on, you will be in the grip of a human emotion that the good Lord, or more likely his nemesis, created just for entrepreneurs. — Wilson Harrell, Inc. Magazine, 1987

At that time, I didn’t know exactly how to describe what I was going through. Then, while I was delving into entrepreneurship, I stumbled upon an old Inc. article by Wilson Harrell. Here, this successful entrepreneur described a specific feeling that only other entrepreneurs were supposed to experience.

Wilson Harrell named this emotion “entrepreneurial terror”. And, even though I have nothing to do with entreprenership in the strict sense, I could deeply relate with the “roller-coaster ride” described by Harrell.

In order to demonstrate how this peculiar form of terror is common among entrepreneurs, Harrell suggested to go to one of them and ask: "So, how are you coping with terror?" According to him, such question would trigger some surprise, yet it would be immediately understood by the fellow entrepreneur. Now, I believe that the reaction of many of my friends, especially the ones involved in academia or in the creative industries, wouldn’t be that different.

Today, exactly 30 years after the publication of Harrell’s article, any kind of human activity or endeavor is understood thorugh an entrepreneurial perspective. This is partially due to the propaganda carried out by “professional” entrepreneurs themselves. Like Reid Hoffman, co-founder of LinkedIn, who introduces his book by quoting Muhammad Yunus. Here, the Bangladeshi social entrepreneur declares: “All human beings are entrepreneurs. When we were in the caves we were all self-employed […] finding our food, feeding ourselves. That’s where human history began […] As civilization came, we suppressed it. We became labor because they stamped us, ‘You are labor.’ We forgot that we are entrepreneurs.” This is how entrepreneurship turns into entrepreneurialism, an ideology that naturalizes risk-taking and self-determination. And while doing this, it expands entreprenerial terror to the whole social spectrum.

As you probably know, there is another term that is often associated with this now widespread form of terror. The word is ‘precarity’. While precarity indicates the very content and context of this fear, entrepreneuralism is meant to offer an escape from that. Both are constitutive elements of the current social reality. Here’s a one-liner that highlight the relationship between precarious work and entrepreneurialism. “Can’t find a job, becomes an entrepreneur.” As I’ll show you afterwards, the choice of the Success Kid meme is not accidental.

The reciprocal influence between an entrepreneurialist regime and pervasive precarity, their ambivalent coexistence, is what the concept of the Entreprecariat refers to. To articulate some of the ways in which this mutual influence takes place, I’d like to introduce what I would call a postulate of the Entreprecariat: The more precarity is present, the less entrepreneurialism is voluntary.

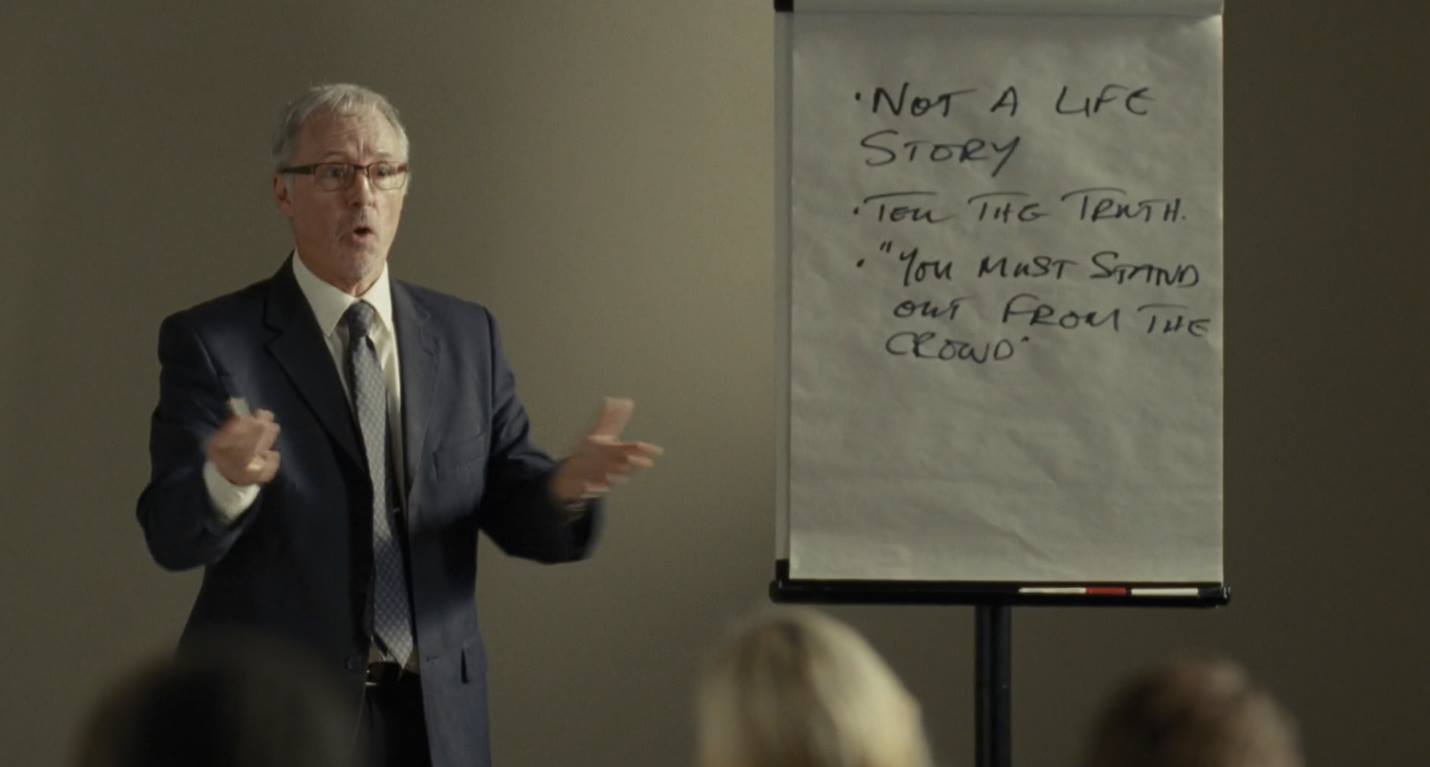

The postulate is well exemplified by a scene of “I, Daniel Blake”, a 2016 movie by Ken Loach on the nightmare of workfare in the UK. Here, a group of unemployed people is required to take a course to improve their chances to find a job. According to the course coach, in a context characterized by the scarcity of available positions, it is imperative to “stand out from the crowd”. This attitude implies the understanding of individuals as competitors, as micro-companies constantly seeking attention through personal publicity.

#whatdesignissupposedtodo pic.twitter.com/NFAtc0JndS

— The Entreprecariat (@silvi0L0russo) 25 maart 2017

The paradigm of a person as micro-company is so pervasive to be almost invisible. We find it for instance in the field of creative industries, where a mongrel literary genre mixing self-help and creative inspiration is emerging. A case in point is the book Don’t Get a Job Make a Job, which adapts a series of generic jobseeking platitudes to the target group of creative graduates. In its introduction we encounter another peculiar aspect of the entreprecariat: a cognitive dissonance in which subjects face the hardships of finding a job while at the same time being expected to address “the biggest problems we face today”, like poverty and war.

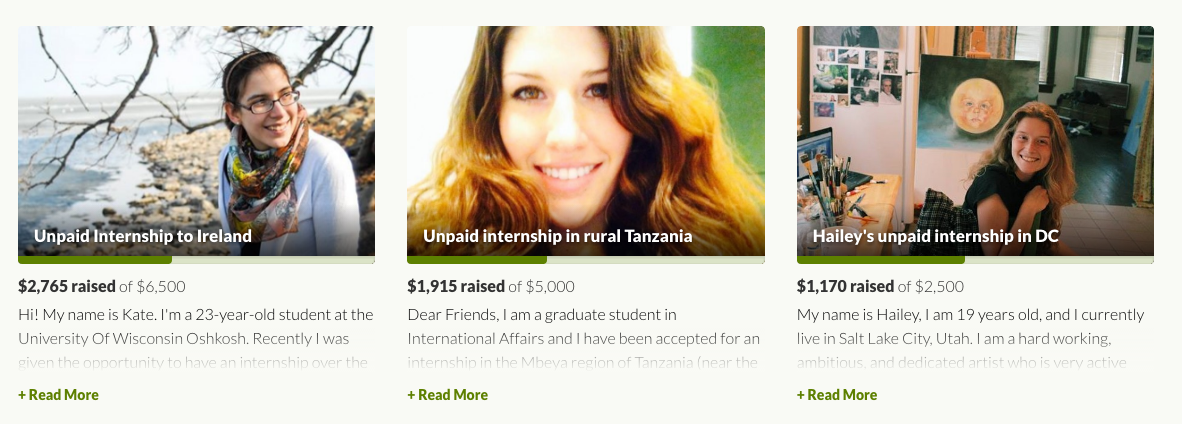

The blending of a forced entrepreneurial attitude with specific instances of precarity is particularly evident in the context of personal crowdfunding. Browsing GoFundMe we stumble upon hundreds of young graduates that cannot afford unpaid internships, which often represent a necessary step to land a job. So, they smile at the camera and passionately describe their interests and academic achievements while detailing their specific financial needs. They cheerfully advertise their personal burden.

Clement Nocos is one of them, a political science graduate from Canada who got accepted for a prestigious unpaid internship at the United Nations, a “one-time-only opportunity”, as he calls it. Not only Nocos produced a somehow ironic 4 minutes long video to advertise his campaign, he also conceived a series of “perks” to be offered to particularly generous donors.

In a long post on Medium, Nocos explained in detail the reasons and the results of his campaign. The above header is a good summary. Eventually, Nocos was able to raise less than $2000 out of the 6000 he asked for.

The internet is full of portmanteau words that work in combination with the word ‘entrepreneur’. Recently, I started to collect them and I created a list including telling neologisms like “sofapreneur”, “dadtrepreneur”, or even “wantrepreneur”. Given my preoccupation with compulsory entrepreneurial endeavors resulting from different types of precarious conditions, I decided to come up with yet another blendword. A sadtrepreneur is a person that unwillingly behaves as an entrepreneur and therefore is not so happy about it.

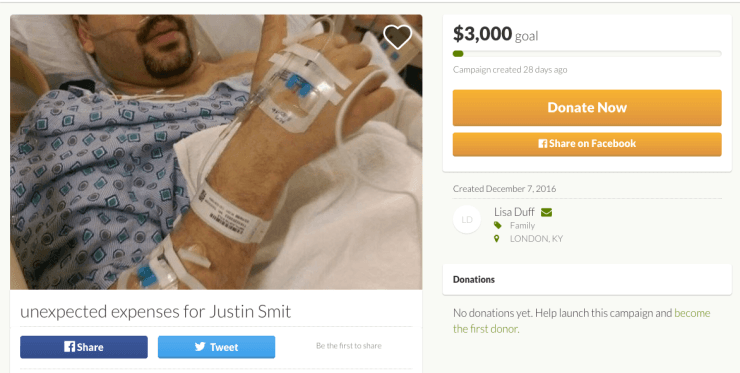

Crowdfunding platforms like GoFundMe, YouCaring and Generosity, are full of sadtrepreneurs. Here, the amount of people asking money for unexpected medical expenses is striking. It isn’t too much of a surprise then the fact that more money were raised on GoFundMe than on Kickstarter, and that almost 70% of the U.S. crowdfunding donations were offered to a person in need.

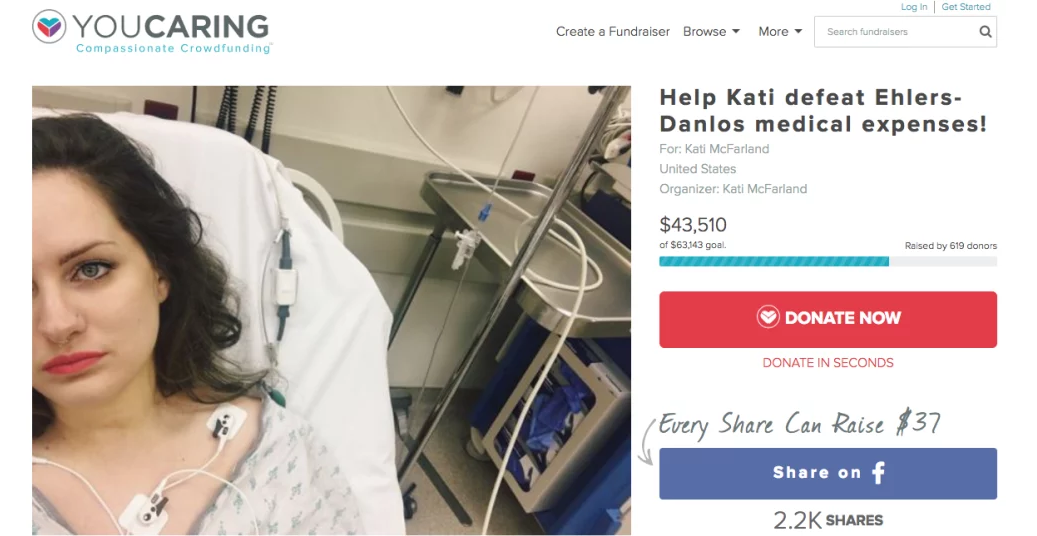

While some users fill their profile only with a short blurb, some other include professionally-shot videos or intimate pictures of their lives, sometimes depicting medical treatment. For her campaign, Kati McFarland chose YouCaring. Kati is a young Arkansan suffering from Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, who published pictures of herself while hospitalized together with financial summaries of her medical expenses.

The three dimensions of the precarious described by political theorist Isabell Lorey coexist in these medical campaigns. First, the ineluctable precariousness of life, characterized by the unpredictability of accidents and illness. Second, ‘precarity’, which is both a discoursive frame to socially address precariousness and a means of creating hierarchies of need, that in the case of crowdfunding are mediated by different scales of visibility. Finally, governmental precarization, the governing and self-governing through insecurity, which includes the erosion of welfare state forms of protection like basic health care and thus imply the destabilization of the ones that require them.

The Precarious Subject as Media Company

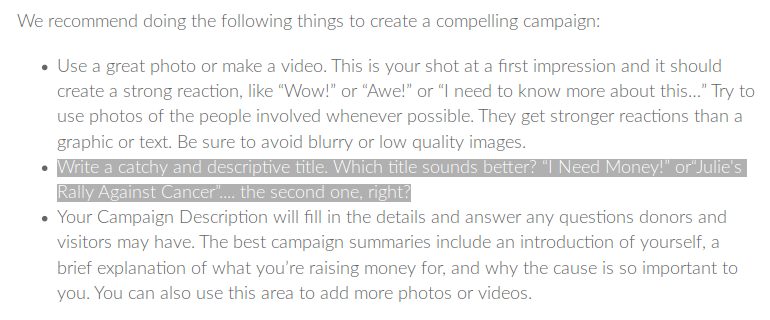

The success of these personal crowdfunding campaigns is strictly related to the user’s ability to operate as a media company, acting simultaneously as a copywriter, a photographer, a social media manager, and an accountant.

Often, the platforms themselves offer tutorials and tips to improve the quality of a campaign, sometimes including extremely generic suggestions such as avoiding blurry pictures. A title needs to be “catchy” in order to stand out from the plethora of running campaigns. In this scenario, the access to an informal means of protection against emergencies turns into a race where online media literacy is a valuable competitive advantage.

Think of your cancer as the origin story a tech startup tells about itself on the About section of its website. — Luke O’Neil, Esquire, 2017

In a recent investigation for the Esquire, journalist Luke O’Neil draws a direct parallel between medical crowdfunding and the ecosystem of tech entrepreneurship. Here, O’Neil sarcastically associates the presentation of GoFundMe users’ medical history to the stereotypical narrative of tech startups, implicitly revealing a similarity between an appeal to charitable spirits and a pitch to a venture capital firm.

While reading O’Neil’s piece, I was reminded of a campaign which effectively combined personal necessity, the amassing of relational capital given by virality, and a strategic use of media literacy. In 2015, the boy who impersonated the ‘Success Kid’ meme, now 8 years old, took advantage of his online popularity to fund the transplant of his father’s kidney. Significantly, on the Verge the news was published under the category of entertainment.

Disrupting Precarization

I’d like to borrow for a moment the startup lingo to discuss some of the attempts to “disrupt” precarization and the dilemmas related to this effort.

Precarity signifies both the multiplication of precarious, unstable, insecure forms of living and, simultaneously, new forms of political struggle and solidarity that reach beyond the traditional models of the political party or trade union. — Rosalind Gill and Andy Pratt, 2008

While precarity is generally understood as a mixture of diverse forms of instability and insecurity, Rosalind Gill and Andy Pratt suggest that the term can also refer to original modes of political struggle.

This is the case of San Precario, an icon that made its first appearance in 2004 and became an ante-literam meme against the exacerbation of labor precarity. San Precario exploited and subverted the deep Catholic roots of Italy producing a mass of devotees and its own heretic liturgy. A couple of years later, the MyCreativity Network, a group formed around a series of events that took place in the Netherlands, proposed a reality check of Richard Florida’s idealistic image of the creative class. Instead of focusing on notions of empowerment and autonomy, the group discussed self-exploitation, insecurity and the emergence of a “creative underclass”.

Nowadays, more than a decade after these efforts, the prevalent image of the precarious subject in the Italian media landscape is an unflattering one. The above comic strip allegorically illustrates it: being precarious means walking on a tightrope placed above the quicksands of unemployement, having to find a balance between subjugation and deference.

Given the pervasive entrepreneurial pressure to think strategically of one’s own “personal brand”, building social cohesion around the acknowlegment of shared forms of precarity is not an easy task. In other words, not many people would comfortably identify as precarious on LinkedIn or even Facebook.

Bringing precarity to the table is often understood as whining, and as we are taught, whining is for losers. These losers are generally the so-called millennials, also categorized as lazy and entitled. Millennials should really take a leaf from the book of actual entrepreneurs, who never complain and “get things done”.

To summarize, this state of things causes people not to come out as precarious, but to be outed as one.

Doing PR against Precarization

Is there a possibility to combine compulsory creative entrepreneurialism with genuine expressions of precarity? In other words, is it possible to do PR through precarity and against precarization?

To answer this question, I’d like to go back to the the crowdfunding stories I mentioned. Last February, Kati McFarland attended a public meeting with a senator who advocated the repeal of the Affordable Care Act. She took the floor and explained that without such measure her life would be at risk. Of course, the media attention that McFarland got thanks to her intervention had a positive effect on the donations to her campaign. But at the same time, her story became symbolic of all the patients endangered by ill-advised policy making.

Needing to differentiate himself from the other graduates campaigning on crowdfunding platforms, Clement Nocos decided to create a podcast. Initially focused on the grinds of his personal journey as an intern in New York City, the podcast soon turned into an instrument of advocacy against unpaid internships.

In one of the latest episodes, Nocos interviewed Nathalie Berger and David Leo Hyde, a duo that organized an extremely effective action to call attention to the issue of unpaid internships. Given the steep cost of living in a city like Geneva, Leo would carry out his work as unpaid intern at the United Nations, while living in a tent.

Here we see Hyde, who is currently shooting a documentary on unpaid internships together with Berger, speaking about the action in the context of a TEDx, a conference format born in the Silicon Valley and characterized by a highly recognizable aesthetics and a very profitable business model.

The cases I discussed denote a high degree of ambiguity emerging when entrepreneurialism meets precarity. Far from being uniquely the result of one’s own passion, entrepreneurially performed “creative” undertakings are increasingly becoming an obligation. More and more people reluctanctly join the ranks of the Entreprecariat, a novel kind of creative underclass whose very medium is constituted by its members’ personal necessities.

Thank you.

Also published on Medium.