Charles van den Heuvel started to make clear that he is not a wikipedian himself. But he has been involved in various projects on annotation and visualization in history, web archiving for

research and Web 2.0 in the Humanities. He worked for various Dutch universities, research

institutes and has worked as librarian. Expressing his interests in Paul Otlet, he wonders how we should present knowledge – stressing the importance of interfaces and the possibilities of different visual forms.

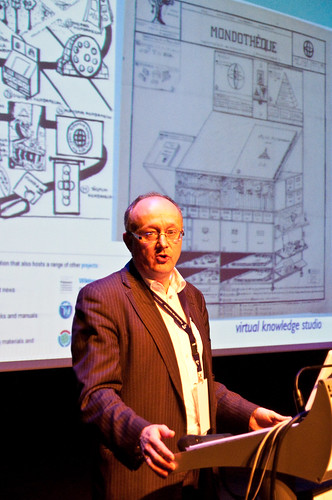

Otlet started to work on an analogue network based on micro-film in the beginning of the 1900s, which is known as the Encyclopaedia Universalis Mundaneum. It was a hierarchical network, consisting of different sorts of institutions, connected to sister networks. There would be workstations at home (Mondotheque). Snippets could be added. (Thanks for clearing this up a bit, Charles. See his comment below.)

Charles continues with stating that these insights Otlet gives us can still be applied to the Web 2.0 of today.

Otlet wanted universal knowledge. Something that was always up to date, always growing, on which people worked together. He was convinced that it shouldn’t be a book. It might be conveyed in a more efficient way, he thought. The important thing was to capture the most essential ideas in the form of snippets, which could be taken apart or be combinend. He envisioned a universal network of documentation, something that could be built up for the future and could be re-used. In short: it was about purification, so snippets could reformatted later for the appropiate goal. Once documentated, the information could then be molded into, for instance, museums or encyclopedias. But of course, Charles notes, these small snippets are hard to manage. That’s why Otlet came up with a classification system. In this way, point-of-views could be created. He mentions ‘personal encyclopedias’, taken from the larger network.

Charles expresses his interest in data arrangements and enrichment, which can be: additions, analyses, PoV, the relations with other objects. He points to some scholar-like schemes of annotation: HarVANA, GenTech and http://www.facetag.org. But these have built-in scientific authority, again.

He draws a parallel with Wikipedia: in his eyes, it is still too much organised as paper. Too much weight is being placed on editing lemma’s and above all it is not exploiting the linking abilities to full extent. For instance, Wikipedia’s edit history is hard to read (he shows a screenshot of a edit history page). This interface could be presented in a different way.

Charles pleas for annotation. He shows the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. He thinks it’s interessting because of the projects around it, which feed it, like The Indiana Philosophy Ontology Project (a taxonomy system). He likes the registration method. It’s not very strict, but still it gives a good general idea about the profile of its users. He then shows the InPhO Idea Tree for mapping the information.

He concludes with the following points:

>> A plea for historical study for protocals and interfaces. Especially interfaces. The built-in authority of contemporary interfaces is not new.

>> Editing, it is not sufficient. Problems are coming from the fact that everyone is editing. It’s very difficult to contribute. Rewrite everything? I’m not doing that. Sometimes you just want to give a small annotation only and you do not want to join the big discussion. The narrative element sometimes stands in the way.

>> Hybrid wikis. Let it happen. Fine. He doesn’t see a problem. Lemmas and annotations can be analysed. Fictional or real names, lays or experts, there is no problem – also not technological.