During the Showcase of the Digital Publishing Toolkit Michael Murtaugh gave a presentation entitled Towards a hybrid workflow: editor, designer and developer UNITE!, that resonated strongly with my experience of creating The Volkskrant Building ebook by Boukje Cnossen and Sebastian Olma. In a previous blogpost I half-heartedly criticized the top-down dynamic experienced during the development of that publication. Now I’d like to pick up where I left and try to turn my frustrations into constructive ideas, that might be useful in the production of hybrid publication within small, low-budged, DIY contexts.

I am critical not of a division of labor in the production of publication. I believe each of the actors involved, being either an author, editor, designer, or developer, should work in his/her area of expertise. Yet, I firmly oppose the situation where each of these actors develop his/her share of the publication in an island, only interrupted by sporadic contacts with the other actors, taking part in the collective and complex effort of publishing a book in more than one medium.

Such criticism begs the question: How can publishing workflows change into collaborative, horizontal, flexible and inventive environments, which can resolve and profit from the challenges brought by hybrid publishing? How can teams of authors, editors, developers and designers work collaboratively under a joint and self-reflective workflow, instead of a series of parallel and independent workflows?

Miriam Rasch (editor for the Institute of Network Cultures’ publications, in which I have worked as a developer) makes a good point on a blogpost where she mentions her necessity as an editor to proof-read the publication’s text in its designed form. This prerequisite is easily understandable. A carefully designed publication encourages a more focused reading experience than a computer screen or the printout of a MS Word document. Rasch further explains how the corrections’ are implemented in INC’s hybrid publication: “usually marked by the editor and then issued to the designer, who will process them in the InDesign file, and to the developer who will do the same in the EPUB”. Rasch argues that “it seems impossible to avoid multiple work on corrections, meaning both editor, designer, and developer might have to put them through in their respective files”.

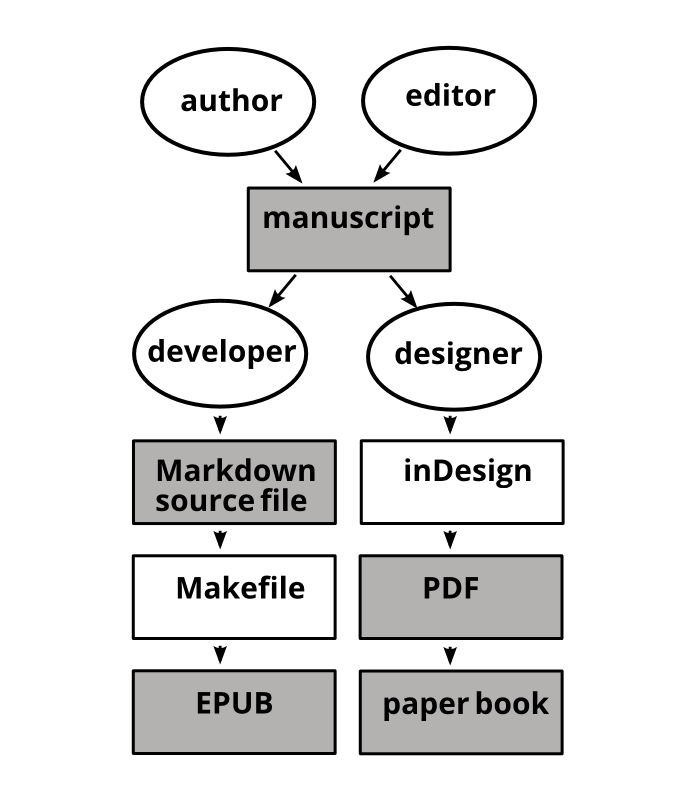

Rather than calling the described approach a workflow, I would risk describing it as a workflow made of multiple workflows, which develop in parallel to each other. The figure bellow attempts to present a visual representation of a parallel workflow. Each actor works on his/her stream, aiming for a specific output. The streams don’t intersect, and changes such as corrections, have to be implemented individually in each stream, from top to bottom.

I disagree with Miriam Rasch when she affirms that “it seems impossible to avoid multiple work on corrections”. And strongly believe that the parallel workflow INC has so far followed is not only inefficient. It is a handicap, when applied to hybrid publishing, ultimately forcing publishers to exclude the possibility of publishing works in more than one format.

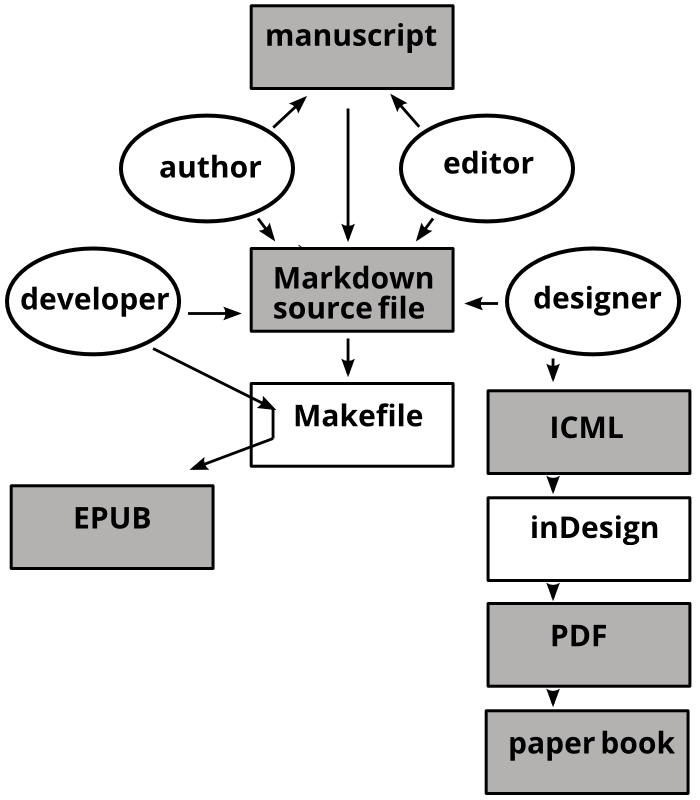

How to work on a single, collaborative workflow? Contrary to what Miriam Rasch argues I am convinced that the implementation of corrections does not need to be repeated for each of the book’s outputs. In my view, a collaborative workflow structured around source files and a version control system, can cut down this process, and others which would normally require an implemented across the multiple publication’s output, into a single implementation. The following figure presents a possible visual representation of such collaborative workflow.

In such workflow the Markdown is the markup language chosen for the source files. They constitute the malleable and changeable building blocks from which the workflow’s outputs are generated. Git – the distributed version control system –, is both the project’s safety net and the link between its various actors. It keeps track of changes in the source files, and syncs them across the source file copies kept by author, editor, designer and developer. Working under this scheme allows all the actors involved in the workflow to intervene upon the source files, and be sure that their changes will be incorporated into the source files kept by all the other actors.

Like in the current INC’s workflow for hybrid publications, the proposed collaborative workflow begins with author and editor working on the manuscript in .docx format. The editor applies a style guide to the manuscript, which make for a seemingly conversion to Markdown. Once the manuscript is correctly formatted it is converted into Markdown source files, and never used again.

The next stage revolves entirely around the Markdown source files – here my proposal starts to diverge from INC’s current workflow. Whereas in the current workflow Markdown source files are only of interest to the developer and at times the editor, in proposed collaborative workflow all actors work on the Markdown source files. They all contribute to its preparation for the next stage of conversions. At this stage, among other actions, the colophon is introduced, footnotes are checked, figures placed, URLs are hyperlinked.

Once all this supplementary information has been introduced into the Markdown source files the workflow enters in its conversion stage. The source files are converted into the various output formats and the workflow splits into branches, dedicated to each of the outputs. Such separation does not mean that the actors will become disconnected, instead they remain connected through the source files. To exemplify this interconnection of production branches take the case of last minute corrections. In this scenario the editor receives a draft of the design for paper book. While reading it she finds typos and elements that need to be altered. In a collaborative workflow she can implement the necessary changes directly to the Markdown source file. Both designer and developer, being notified of such change, sync their Markdown source files to the editor’s version – a trivial process in Git tracked projects. The three now have their Markdown source files in their latest version, which include the editor’s last minute changes. Both designer and developer only need to integrate those changes into their respective projects, destined to become one of the publication’s outputs. The EPUB developer can incorporate the introduced changes by producing a new EPUP version, via a Makefile, as described in Making the VolkskrantBuilding.epub blogpost. For the designer, changes can be incorporated into the inDesign (or Scribus) project through the conversion of the Markdown source file into an ICML file – As described by Silvio Lorusso in the Markdown to Indesign with Pandoc (via ICML) blogpost, importing an ICML file into an inDesign project permits updating both content and structure, without affecting the project’s design decisions. In both cases, content changes in the source files, can be incorporated into the various design projects, destined to produce the publication’s outputs, without affecting any or reverting prior design and development work.

The advantages of such collaborative and lean working methodology for hybrid publications seems clear. I believe it promotes an efficient architecture where time isn’t wasted on replicating the same actions for each of the publication’s output. More importantly, it fosters a dynamic where editor, designer, developer and author work closer and interdependently, and the output is only one conversion away from the publication’s source. If instead, publishers choose to develop hybrid publications under the same methods they have developed for single-output publications, I am inclined to believe they wont be able to sustain the demands of such approach, and hybrid publishing will be nothing more but a distant dream, that ended up costing too much time and money.