This text is a contribution to MoneyLab Reader 2: Overcoming the Hype, edited by Inte Gloerich, Geert Lovink and Patricia de Vries. Read it here and download it for free as PDF or EPUB. The text was also published in Italian on Not.

Crowdfund Everything

What is crowdfunding for? One could assume that, if asked such a question, most of the people that know this word (according to a study by the Pew Research Center, 61% of Americans have never heard of it[1]) would refer to innovative products or services, album releases, documentaries, books, videogames, or comics. In other words, they will be inclined to associate crowdfunding with the endeavors of tech startups and the creative industries.

This assumption is partly confirmed by the data available on the highest funded crowdfunding projects[2]. Besides the great number of cryptocurrency-related campaigns run independently or through Ethereum in the top ten, most of the projects were hosted by either Kickstarter or Indiegogo, both platforms generally used to finance creative or innovative undertakings. Of course, the sheer amount of money raised lures a comparable magnitude of media attention, thus establishing a feedback loop between the aggregation of a large public through big news outlets and financial success. This is the case of Pebble, a smartwatch idea which collected more than 40 million dollars during three separate Kickstarter campaigns. This massive crowdfunding achievement didn’t prevent the company from shutting down after four years of activity.

Another reason why crowdfunding is generally associated with creativity and innovation has to do with its origins. The practice of collecting monetary contributions from internet users emerged primarily as a means of financing artistic ventures. One of these was the U.S. tour of the British rock band Marillion, made possible in 1997 by the $60,000 of their fans’ online donations[3]. This early instance, in which online fundraising wasn’t yet a streamlined process, reminds us that crowdfunding itself is an entrepreneurial idea first implemented in the context of the arts. Thanks to crowdfunding, what was an informal exchange with an audience was turned into a business model. Now, two decades later, nurturing a community is considered one of the fundamental features of crowdfunding[4].

The managerial impetus of these musicians adds a new layer of meaning to the notion of creative destruction formulated by Viennese economist Joseph Schumpeter, where a new commodity, technology, type of organization, etc. erodes preexisting economic structures and creates new ones[5]. Since the relationship with fans is part of an artist’s practice, using it to gather donations is a financial invention where the artistic, creative component is fundamental. Crowdfunding originates as an idea that creatively deteriorates the role and position of middle men and evolves as an expression of creative entrepreneurialism, where there is no clear boundary between the ‘creative’ and the ‘entrepreneurial’. More specifically, the former becomes a function of the latter and vice-versa. As the band recounts:

We then sacked the manager. We emailed the 6000 fans on our database to ask, “Would you buy the album in advance?” most replied “yes.” […] That was the crowdfunding model that has been so successfully imitated by many others including the most successful, KickStarter.

Surprisingly, despite the artistic legacy of crowdfunding and the recurrent media coverage of innovation, the primary destination of online contributions is neither edgy technology nor artistic work, but personal fundraising. While 68% of U.S. donors have contributed to campaigns launched to help a person in need, only 34% funded a new product and 30% decided to support musicians and other kind of artists[6]. Furthermore, GoFundMe, a platform focused on social and personal campaigns, surpassed the bar of $3 billion dollar raised in 2016 while Kickstarter reached that goal only one year afterwards[7].

GoFundMe is not the only platform mainly devoted to personal crowdfunding. There is also YouCaring, GiveForward, and even Indiegogo has its own parallel charity crowdfunding platform called Generosity. Does their core business make them different from, say, Kickstarter? Do they incarnate a fundraising logic different from the one of crowdfunding sites focused on art and invention? In other words, is there a fundamental difference between asking money for a medical emergency and an IoT gadget? In the following sections I describe a series of campaigns that reveal the way in which personal crowdfunding encourages, and to some extent requires, creative entrepreneurialism. The reason why I am specifically interested in the campaigns initiated by these ‘entrepreneurs of the self’ is that while undergoing the dynamics of crowdfunding, they expand its scope in different ways.

The Unpaid Intern as Media Company

Nowadays, internships represent one of the few viable paths to initiate a career in the most diverse professional sectors. The internship, which is originally meant to be a learning experience, is therefore reframed as an opportunity to eventually land a job. Because of high demand, companies and institutions –even well-established ones– can easily offer internships that are paid little money or not paid at all. In other words, the internship is understood as a required investment to enter the labor market. It isn’t hard to appreciate the way in which these unpaid internships contribute to exacerbate class advantage, since only the individuals who have enough financial stamina are able to afford this point of access to professional life.[8]

What about all the others? They need to come up with creative solutions. Crowdfunding is one of those. At the time of writing, a search for “unpaid internship” on GoFundMe generates almost five hundred results, while the campaigns generically related to internships are more than ten thousand. These campaigns feature young graduates smiling at the camera, passionately describing their interests and academic achievements while detailing their specific financial needs. The descriptions, which fluctuate between very elaborate pitches and extremely concise blurbs, are characterized by a mongrel literary genre in which the diary, the résumé and the business plan converge. This new literature already has its own manuals, like a GoFundMe guide for a successful education-related campaign[9].

The story of Clement Nocos is at the same time an exemplary case of crowdfunding an unpaid internship and an exceptional one. In 2016, Nocos, a Master of Public Policy graduate and activist from Canada, got accepted for a prestigious internship at the United Nations, a “one-time-only” opportunity, as he somehow ironically defines it.[10] There was only one drawback: the internship was unpaid, a decisive problem given the steep cost of living in a city like New York.

For his campaign, Nocos chose Generosity, Indiegogo’s side-platform “for human goodness”, because of the absence of an expiry date, the possibility of adding ‘perks’ and the regular disbursement of funds. In order to gather attention, he produced a four-minute-long videoclip explaining why people should donate to his campaign. To make the video effective, Nocos, a political scientist, crafted his message with the aim of entertaining his audience: he included some photoshopped images of himself and a few ironic intermezzos accompanied by an old school hip-hop soundtrack. Furthermore, Nocos took advantage of some promotional strategies, such as asking only half of the money he needed or offering a United Nations mug (“not for sale!”) to particularly generous donors. The campaign’s description resembles the FAQ section of a website, including such questions as “Why should I help you?” and “What do you need?” At the bottom of the page, Nocos offers a breakdown of his expenses (250$ per month are for food). His efforts included a “crafty social media campaign”, deemed almost indispensable by the platform which constantly insists on sharing public updates.

In a post on Medium, Nocos explains the reasons and the results of his campaign in detail[11]. As he puts it,

it seems like getting on the internship grind was the only way to get that work experience that has apparently become necessary for securing at least precarious, entry-level employment.

He describes crowdfunding as his only viable choice for financing the internship, while still having to deal with student debt (“Why Crowdfunding? What else do I got?”). In preparation of his campaign, Nocos realized that he wasn’t the only one trying to finance his internship through crowdfunding, and this is why he “felt the need to differentiate”. So, he started a blog and a podcast about the grinds of internship at the United Nations (12 episodes to date). Out of the $6,000 he aimed to raise, he was able to gather less than $2,000 over a year. Reflecting back on his experience, Nocos, who was skeptical of crowdfunding in the first place, could only confirm his original feelings. He speaks of social media fatigue, he mentions the uneasiness of having to ask money to a circle of friends who are often going through a tough situation, and he concludes that “the crowdfunding market has literally crowded itself out when it comes to people asking for money to replace labour income for their unpaid internships.”

Despite the meager loot he gained, Nocos’ efforts produced an additional result. It didn’t take long before self-promotion turned into a critique addressing the very issue of unpaid internships. In his podcast “The Internship Grind”, he discussed the Fair Internship Initiative, the book Intern Nation by Ross Perlin, and he interviewed Nathalie Berger and David Leo Hyde, currently shooting An Unpaid Act, a documentary on unpaid internships and precarity. Nonetheless, looking back at this activity, Nocos humbly acknowledges the ambivalence of ‘selfishly’ lobbying for a personal cause and addressing a structural condition:

But to be frank, the podcast isn’t all just about documenting this kind of crappy quirk of the modern labour market. It was intentionally self-serving, in a way, to draw attention to my own crowdfunding campaign and make it more visible for potential donors.

What role did Nocos play in his own campaign? As he was aware that crowdfunding success is strictly related to the user’s ability to operate as a media company, he acted simultaneously as a copywriter, a video-maker, a social media manager, and an accountant.

Call to Action Meets Activism

On personal crowdfunding platforms, it is not uncommon to read about a broken arm, a heart transplant, or a rare disease. In these cases the campaign goals range from a few thousand dollars to more than half a million. $60,000 was the amount asked by Kati McFarland, a 25 year-old photographer from Arkansas suffering from Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, a genetic disorder causing many different complications like fainting, fatigue and stomach paralysis. She sums up her condition by saying that she “can barely walk /stand / eat w/o severe pain/ dislocations / vomiting / blackout”[12].

After her father suddenly passed away, McFarland found herself alone struggling to manage her medical expenses that exceed by far the benefits provided by the State. This is why she started a fundraiser on YouCaring, a platform that unlike GoFundMe doesn’t take any fee on the donations[13]. McFarland’s campaign doesn’t look as carefully crafted as Nocos’ one. She doesn’t have a video on her page, only a few images showing her while being under medical treatments and some screenshots of the related costs. The first part of the description follows the usual script of personal storytelling while the second part is an extremely detailed cost breakdown filled with medical technicalities. Given the short attention spans internet users have grown accustomed to, it isn’t hard to understand why it took her more than 7,000 re-blogs and shares to reach a preliminary goal of 1,200 dollars.

Detail from the interface of Generosity.

Things changed for McFarland when she attended a talk by congressman Tom Cotton, an ardent opponent of Obamacare, the healthcare act that the new Trump administration is trying to repeal. During the event, she took the floor and explained to the congressman that without the coverage provided by the Affordable Care Act she would lose her life (“I will die. That is not hyperbole.”). McFarland asked him whether he would commit not only to the repeal of the act, but also to building a proper substitute. This is when the audience exploded in a big round of applause. After Cotton tried to skirt the issue, the crowd vocally expressed its disapproval by repeatedly shouting “do your job”[14].

After being published on the internet, Kati McFarland’s intervention gained some degree of virality. Then, she started to see her fundraiser grow at a surprisingly increased rate. In the meantime, McFarland had been invited to talk about what happened on several TV news programs, where she asserted the need to give a face to the collective demand for accessible healthcare. However, this effort wasn’t disconnected from the promotion of the campaign, a matter of life and death for her:

there are many things I wish I could have said […] but unfortunately I just had to focus on shoehorning in the link to this fundraiser (probably to Don Lemon’s chagrin), but you gotta do what you gotta do when medical bills are involved.”[15]

Of course, the media attention that McFarland got thanks to her intervention had a positive effect on the donations to her campaign. But at the same time, her story became symbolic of all the patients endangered by ill-advised policy making. In a similar way to Nocos, Kati McFarland had to deal with the highly ambiguous space where personal promotion goes hand in hand with the attempt to shed light on a structural deficit.

First as Arts, Then as Tragedy

Around 2007 a meme started to circulate on the internet. It was the picture of a kid on a beach holding a fist full of sand, with an expression of pride on his face. The picture became known as “Success Kid” and it is still used nowadays to either express frustration or describe situations in which one is “winning”[16]. In 2015, Sam Griner, the boy impersonating the ‘Success Kid’ meme, now 8 years old, availed himself of his online popularity to fund the transplant of his father’s kidney. A campaign was launched on GofundMe including only one family picture with Sam in the middle and a concise account of the calamity. The campaign raised more than $100,000, thanks to which the transplant was eventually possible. Significantly, on The Verge, the news was published under the category of entertainment[17].

Despite its happy ending, this vicissitude can be read as a cautionary tale about the role played by social and news media attention when it comes to personal crowdfunding. Here, a series of more or less arbitrary criteria increase the chances of a campaign’s success, although without guaranteeing it. After all, there is still no such thing as a science of virality. Such vagueness is confirmed by the overly generic tips offered by GoFundMe itself: “avoid blurry pictures […] Write a catchy and descriptive title. Which title sounds better? ‘I Need Money!’ or ‘Julie’s Rally Against Cancer’…. the second one, right?”[18] A title needs to be “catchy” in order to stand out from the plethora of running campaigns. In this scenario, the access to an informal means of protection against emergencies turns into a race where online media literacy is a valuable competitive advantage.

Message from a donor to the ‘Success Kid”s father.

As writer Alana Massey points out, crowdfunding for medical care represents the most radical transformation of fundraising since the ’80s. At that time, another crucial shift was taking place: charities were converting their model into an individual-based sponsorship. Instead of being asked to “sponsor children in need”, donors would be now invited to “sponsor a child in need”[19]. The singularization of solidarity which is also embedded in crowdfunding sites is often understood as a positive feature, because it offers “the opportunity to help one specific person and help change one person’s life.”[20] Furthermore, the individual-based relationship between the donor and the beneficiary is reinforced by the direct contact between them offered by crowdfunding platforms.

Considering the telegraphic style of several campaigns, one could assume that many of those are only meant to address family members and friends who are already aware of the issue at stake. In this case, crowdfunding offers a convenient interface that facilitates the coordination of fundraising. But frequently the hope is to reach a crowd of strangers and therefore compete for their attention. A crowd whose choices are likely reflective of several biases[21]. Among them, there is one that sounds particularly gloomy when associated with personal crowdfunding: survivorship bias, the habit of focusing on successful past experiences while ignoring the others[22]. As writer Anne Helen Petersen puts it, “crowdfunding is fantastic at addressing need — but only certain types, and for certain people.”[23]

Crowdfunding success is bolstered by online media dexterity. Journalist Luke O’Neil emphasizes this aspect: “I often joke lately that I used to think I’ve wasted my life on Twitter, but it might actually come in handy when I inevitably need to crowdfund an operation. You have to hustle. You have to market. You have to build your brand.” O’Neil also draws a direct parallel between medical crowdfunding and the ecosystem of tech entrepreneurship. He sarcastically associates the presentation of GoFundMe users’ medical history to the stereotypical narrative of startups, implicitly revealing a similarity between an appeal to charitable spirits and a pitch to a venture capital firm: “Think of your cancer as the origin story a tech startup tells about itself on the About section of its website,” he suggests[24].

Emerging from O’Neil’s remarks is the brutal content-neutrality of crowdfunding, no matter whether it is employed to finance the “Coolest Cooler” or used as a means to alleviate the hardships looming throughout the whole spectrum of a lifetime[25]. The way in which Indiegogo introduces Generosity reveals the way in which crowdfunding is generalized by a mere extension of its target group:

We started Indiegogo in 2008 with a simple idea: Give people the power and resources to bring their ideas to life. Over the years we’ve watched in delight as inventors, musicians, storytellers, and activists pushed the boundaries of our original vision. […] Inspired by the seemingly boundless compassion and creative spirit of our users, we challenged ourselves to do more—this time for the very people and causes that often need help the most. The ones that fall through the cracks. The ones that need a second chance. The ones on the brink. Generosity helps cancer patients with bills and students with tuition. Generosity boosts humanitarian efforts into new countries and helps nonprofits move quickly with their causes. Generosity fills the gap at the end of a tough month and supports the village after the storm[26].

In other words, crowdfunding repeats itself, first as arts, then as tragedy. But while doing so, it preserves the promotional language and entrepreneurial dynamics that characterize fundraising for art or innovation: things like ‘perks’, enforced social media bombardment, strategies borrowed from advertising, and, as Ian Bogost maintains, a semblance of the reality show[27]. All of these aspects, critically addressed by artist and activist Josh MacPhee, survive in campaigns about survival[28]:

Our goal—our imperative—is to harden ourselves and our projects into cohesive, likable, and salable commodities. We wake up as brands, joyously exulting in these flattened, logo-like versions of ourselves. Clean and efficient with soft, smooth corners and antiseptic Helvetica expressions. What is not to love about these new forms, so sleek and attractive on the outside, with the promise of aiding us in the fulfillment of the last remaining human right in our society: the right to be an entrepreneur?

Sadtrepreneurs

During the MyCreativity Sweatshop event, American novelist Bruce Sterling gave a talk entitled “Whatever Happens to Musicians, Happens to Everybody”. He portrayed musicians as “patient zero in the critical injury clinic of the creative sweatshop”. Sterling referred to them as an avant-garde of the precarity experienced by creative workers. He also reflected on crowdfunding as a means to sustain their practice, concluding that wouldn’t be a good idea since “the crowd lacks imagination”[29]. According to Brett Neilson and Ned Rossiter, the creative worker is considered by many the precarious subject par excellence[30]. Now that creative solutions are becoming a crucial means of addressing various forms of precariousness, we might read Sterling’s portrait of musicians as canaries in the coal mine as an alarmingly vivid prediction. The people running campaigns on sites like GoFundMe can be seen as creative workers whose very medium is their own adversities, carrying out a practice sustained by an entrepreneurial attitude that includes management and promotion.

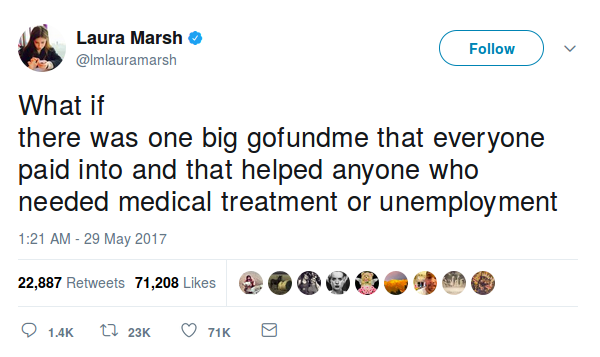

The Web is full of labels referring to specific types of entrepreneurs. Online, we read of kidtrepreneurs, solopreneurs, or even botrepreneurs. Looking at these campaigns, it seems that the more precariousness is present, the less entrepreneurialism becomes voluntary[31]. So, we might introduce yet another blend-word to identify the users of personal crowdfunding sites. Many of those are “sadtrepreneurs”, subjects that unwillingly, or at least ambivalently, behave as entrepreneurs. To them, the creativity needed to run a successful campaign is not a liberating force, but a strategic necessity linked to subsistence or even survival.

Far from being uniquely the result of one’s own passion, entrepreneurially performed ‘creative’ undertakings are increasingly becoming an obligation. More and more people reluctantly join the ranks of a novel kind of creative underclass whose very medium is constituted by its members’ personal necessities. Is there a possibility to combine compulsory creative entrepreneurialism with genuine expressions of discomfort? Is it possible to do PR through precarity and against precarization? In this grim scenario, the stories of Clement Nocos and Kati McFarland reflect the urge to divert attention solely from individual miseries to the broader structural conditions causing them. Would this effort be worth a monumental crowdfunding campaign?

References

- “How to Run a Successful GoFundMe Campaign for College Expenses.” GoFundMe Tutorials. Accessed May 13, 2017. https://pages.gofundme.com/fundraiser-success-tips/college-fundraising-tips/.

- “List of Highest Funded Crowdfunding Projects.” Wikipedia, 12 May 2017. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=List_of_highest_funded_crowdfunding_projects&oldid=780102024.

- “GoFundMe Guide: Six Steps to a Successful Campaign.” GoFundMe Help Center. Accessed 13 May 2017, http://support.gofundme.com/hc/en-us/articles/203604494-GoFundMe-Guide-Six-Steps-to-a-Successful-Campaign.

- “Success Kid / I Hate Sandcastles.” Know Your Meme. Accessed 13 May 2017, http://knowyourmeme.com/memes/success-kid-i-hate-sandcastles.

- Bogost, Ian. “Kickstarter: Crowdfunding Platform Or Reality Show?” Fast Company, 18 July 2012, https://www.fastcompany.com/1843007/kickstarter-crowdfunding-platform-or-reality-show.

- Cohen, Adi. “Donations Pour In For Woman Who Yelled At Her Senator,” Vocativ, 23 February 2017, http://www.vocativ.com/405313/donations-woman-yelled-senator-town-hall/.

- Kazmark, Justin. “$3 Billion Pledged to Independent Creators on Kickstarter.” Kickstarter Blog, 26 April 2017, https://www.kickstarter.com/blog/3-billion-pledged-to-independent-creators-on-kickstarter.

- Lorusso, Silvio. “What Is the Entreprecariat?,” The Entreprecariat, 27 November 2016, https://networkcultures.org/entreprecariat/what-is-the-entreprecariat/.

- Lunden, Ingrid. “Gofundme Passes $3b Raised on Its Platform, Adding $1b in Only the Last 5 Months,” TechCrunch, 18 October 2016, https://techcrunch.com/2016/10/18/gofundme-raises-3b-on-its-platform-raising-1b-in-only-the-last-5-months/.

- MacPhee, Josh. “Who’s the Shop Steward on Your Kickstarter?” The Baffler, 4 March 2014, https://thebaffler.com/salvos/whos-the-shop-steward-on-your-kickstarter.

- Massey, Alana. “Mercy Markets,” Real Life, 11 April 2017, http://reallifemag.com/mercy-markets/.

- Mikelberg, Amanda. “Gofundme Is a Tuition Money Machine in New York City,” Metro, 15 February 2017, http://www.metro.us/new-york/gofundme-is-a-tuition-money-machine-in-new-york-city/zsJqbo—bbddbvpGbRm6.

- Mollick, Ethan. “The Unique Value of Crowdfunding Is Not Money — It’s Community.” Harvard Business Review, April 21, 2016. https://hbr.org/2016/04/the-unique-value-of-crowdfunding-is-not-money-its-community.

- Nielson, Brett and Ned Rossiter, “From Precarity to Precariousness and Back Again: Labour, Life and Unstable Networks.” Fibreculture, no. 5 (2005), http://five.fibreculturejournal.org/fcj-022-from-precarity-to-precariousness-and-back-again-labour-life-and-unstable-networks/.

- Nocos, Clement. “The Crowdfunding Grind: Why It’s Not Paying for an Unpaid Internship.” Medium, 1 August 2016. https://medium.com/@amaturhistorian/the-crowdfunding-grind-why-its-not-paying-for-an-unpaid-internship-96a3d82c0d22#.j3vs4pw2j.

- O’Neil, Luke. “Go Viral or Die Trying.” Esquire, March 28, 2017, http://www.esquire.com/news-politics/a54132/go-viral-or-die-trying/.

- Perlin, Ross. Intern Nation: How to Earn Nothing and Learn Little in the Brave New Economy, London: Verso, 2014.

- Petersen, Anne Helen. “The Real Problem With Crowdfunding Health Care.” BuzzFeed, March 10, 2017, https://www.buzzfeed.com/annehelenpetersen/real-peril-of-crowdfunding-healthcare.

- Precarious Workers Brigade, Training for Exploitation? London/Leipzig/Los Angeles. Journal of Aesthetics and Protest, 2017.

- Preston, Jack. “How Marillion Pioneered Crowdfunding in Music.” Virgin Blog, 20 October 2014. https://www.virgin.com/music/how-marillion-pioneered-crowdfunding-in-music.

- Rhue, Lauren and Jessica Clark. “Who Gets Started on Kickstarter? Racial Disparities in Crowdfunding Success.” SSRN Scholarly Paper. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network, 9 September 2016, https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2837042.

- Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, Routledge, London/New York, 2013.

- Smith, Aaron. “Shared, Collaborative and On Demand: The New Digital Economy.” Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech, 19 May 2016, http://www.pewinternet.org/2016/05/19/the-new-digital-economy/.

- Sterling, Bruce. “Whatever Happens to Musicians, Happens to Everybody.” presented at the MyCreativity Sweatshop, Amsterdam, 20 November 2014, https://vimeo.com/114217888.

- Toor, Amar. “The Internet Just Helped ‘Success Kid’ Raise Money for His Dad’s Kidney Transplant,” The Verge, 17 April 2015, https://www.theverge.com/2015/4/17/8439483/success-kid-father-kidney-transplant-crowdfunding.

[1] Aaron Smith, “Shared, Collaborative and On Demand: The New Digital Economy.” Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech, 19 May 2016, http://www.pewinternet.org/2016/05/19/the-new-digital-economy/.

[2] “List of Highest Funded Crowdfunding Projects.” Wikipedia, 12 May 2017. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=List_of_highest_funded_crowdfunding_projects&oldid=780102024.

[3] Jack Preston, “How Marillion Pioneered Crowdfunding in Music.” Virgin Blog, 20 October 2014. https://www.virgin.com/music/how-marillion-pioneered-crowdfunding-in-music.

[4] Ethan Mollick, “The Unique Value of Crowdfunding Is Not Money — It’s Community.” Harvard Business Review, April 21, 2016. https://hbr.org/2016/04/the-unique-value-of-crowdfunding-is-not-money-its-community.

[5] Joseph Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, Routledge, London/New York, 2013, pp. 83, 84.

[6] Aaron Smith, ibid.

[7] Ingrid Lunden, “Gofundme Passes $3b Raised on Its Platform, Adding $1b in Only the Last 5 Months,” TechCrunch, 18 October 2016, https://techcrunch.com/2016/10/18/gofundme-raises-3b-on-its-platform-raising-1b-in-only-the-last-5-months/. Justin Kazmark, “$3 Billion Pledged to Independent Creators on Kickstarter.” Kickstarter Blog, 26 April 2017, https://www.kickstarter.com/blog/3-billion-pledged-to-independent-creators-on-kickstarter.

[8] Cfr. Precarious Workers Brigade, Training for Exploitation? London/Leipzig/Los Angeles. Journal of Aesthetics and Protest, 2017, pp. 12-3. Ross Perlin, Intern Nation: How to Earn Nothing and Learn Little in the Brave New Economy, London: Verso, 2014.

[9] “How to Run a Successful GoFundMe Campaign for College Expenses.” GoFundMe Tutorials. Accessed May 13, 2017. https://pages.gofundme.com/fundraiser-success-tips/college-fundraising-tips/.

[10] Clement Nocos’ crowdfunding campaign on Indiegogo’s Generosity, https://www.generosity.com/education-fundraising/clem-s-united-nations-internship-blog-podcast/.

[11] Clement Nocos, “The Crowdfunding Grind: Why It’s Not Paying for an Unpaid Internship.” Medium, 1 August 2016. https://medium.com/@amaturhistorian/the-crowdfunding-grind-why-its-not-paying-for-an-unpaid-internship-96a3d82c0d22#.j3vs4pw2j.

[12] Kati McFarland’s campaign on YouCaring: https://www.youcaring.com/kati-mcfarland-588646

[13] YouCaring and Generosity don’t charge any fee. However, a 2.9% is deducted by credit card processors like Paypal, We Pay, or Stripe: https://www.youcaring.com/c/free-fundraising.

[14] Adi Cohen, “Donations Pour In For Woman Who Yelled At Her Senator,” Vocativ, 23 February 2017, http://www.vocativ.com/405313/donations-woman-yelled-senator-town-hall/.

[15] Kati McFarland, ibid.

[16] “Success Kid / I Hate Sandcastles.” Know Your Meme. Accessed 13 May 2017, http://knowyourmeme.com/memes/success-kid-i-hate-sandcastles.

[17] Amar Toor, “The Internet Just Helped ‘Success Kid’ Raise Money for His Dad’s Kidney Transplant,” The Verge, 17 April 2015, https://www.theverge.com/2015/4/17/8439483/success-kid-father-kidney-transplant-crowdfunding.

[18] “GoFundMe Guide: Six Steps to a Successful Campaign.” GoFundMe Help Center. Accessed 13 May 2017, http://support.gofundme.com/hc/en-us/articles/203604494-GoFundMe-Guide-Six-Steps-to-a-Successful-Campaign.

[19] Alana Massey, “Mercy Markets,” Real Life, 11 April 2017, http://reallifemag.com/mercy-markets/.

[20] Amanda Mikelberg, “Gofundme Is a Tuition Money Machine in New York City,” Metro, 15 February 2017, http://www.metro.us/new-york/gofundme-is-a-tuition-money-machine-in-new-york-city/zsJqbo—bbddbvpGbRm6.

[21] A 2016 study shows that Kickstarter crowdfunding projects including photos of Black subjects have a significantly lower success rate. Cfr. Lauren Rhue and Jessica Clark. “Who Gets Started on Kickstarter? Racial Disparities in Crowdfunding Success.” SSRN Scholarly Paper. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network, 9 September 2016, https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2837042.

[22] In 2014, I created Kickended.com, an archive of Kickstarter’s $0-pledged campaigns, to be able to navigate and bring attention to campaigns unable to raise any money, thus opposing the survivorship bias embedded in both news media and the interfaces of crowdfunding platforms.

[23] Anne Helen Petersen, “The Real Problem With Crowdfunding Health Care.” BuzzFeed, March 10, 2017, https://www.buzzfeed.com/annehelenpetersen/real-peril-of-crowdfunding-healthcare.

[24] Luke O’Neil, “Go Viral or Die Trying.” Esquire, March 28, 2017, http://www.esquire.com/news-politics/a54132/go-viral-or-die-trying/.

[25] The ‘Coolest Cooler’ is a cooler equipped with a blender and speakers that raised more than 13 million dollars on Kickstarter.

[26] Generosity’s mission statement: https://www.generosity.com/.

[27] Ian Bogost, “Kickstarter: Crowdfunding Platform Or Reality Show?” Fast Company, 18 July 2012, https://www.fastcompany.com/1843007/kickstarter-crowdfunding-platform-or-reality-show.

[28] Josh MacPhee. “Who’s the Shop Steward on Your Kickstarter?” The Baffler, 4 March 2014, https://thebaffler.com/salvos/whos-the-shop-steward-on-your-kickstarter.

[29] Bruce Sterling, “Whatever Happens to Musicians, Happens to Everybody.” presented at the MyCreativity Sweatshop, Amsterdam, 20 November 2014, https://vimeo.com/114217888.

[30] Brett Nielson and Ned Rossiter, “From Precarity to Precariousness and Back Again: Labour, Life and Unstable Networks.” Fibreculture, no. 5 (2005), http://five.fibreculturejournal.org/fcj-022-from-precarity-to-precariousness-and-back-again-labour-life-and-unstable-networks/.

[31] I call ‘entreprecariat’ the mutual relationship between entrepreneurialism and precarity. Cfr. Silvio Lorusso, “What Is the Entreprecariat?,” The Entreprecariat, 27 November 2016, https://networkcultures.org/entreprecariat/what-is-the-entreprecariat/.

Also published on Medium.