![]()

The computer is first and foremost a calculator. Among the main things it calculates, and thus measures, there is the passage of time. As a result, our laptops and mobile phones are also chronometers. But what kind of time do they take into account? On the first startup, these devices immediately require the local time zone, so that they can connect to the internet and automatically synchronize with the other ones in the network. This connection doesn’t only imply a cancellation of spatial distance but also the possibility of experiencing a sort of telematic jet lag: we wake up and chat with a friend who lives twelve hours away and is already at the end of their day. Sunrise and sunset are merged by means of network dynamics, they are obfuscated.

According to Jonathan Crary, author of 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep, interconnected digital technology represents a privileged battlefield for the defeat of the night, and consequently of sleep, for the latter constitutes "an uncompromising interruption of the theft of time from us by capitalism.” A crusade that was already inherent to the modern project of industrial rationalization.

Before the widespread use of networked computers, in the Western world there were some persisting pockets of resistance, areas where the night had not yet been colonized by production requirements. In 1997 Franco Piperno could still assert that in Italy there was "not a single time, but a multiplicity of times, and some are, unfortunately, incompatible with each other." To paraphrase William Gibson, the absolute temporality of modernity was already here, just not evenly distributed.

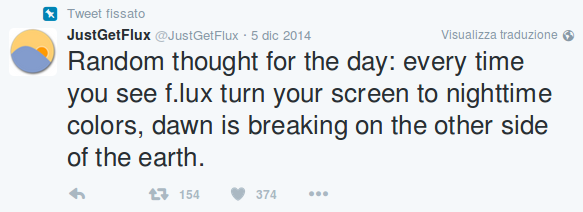

Today things have changed: the Web never sleeps. Global connectivity carries with it a ceaseless wakefulness indifferent to circadian rhythms, that clock inside our body that physiologically tells us when it’s time to stay awake or go to sleep. The absolute, homogeneous, uninterrupted temporality of the network is reflected by screens that emit the same bluish light at any time of day or night. A light that has negative effects on vision, since it is designed for daylight environments, and on sleep, since it inhibits the production of melatonin, creating a vicious circle in which staying at night in front of a screen prompts us to stay there even more.

From f.lux Facebook page

Created in 2009 by two former Google employees, f.lux is an application that aims to solve these problems by automatically adjusting the color temperature of the light emitted by the screen according to the local time and the illumination of the surrounding environment: when the sun goes down, f.lux makes sure that the screen gradually becomes yellowish. Nowadays, seven years later, the solution — only apparently simple — offered by f.lux has become an option available by default on many mobile devices. Generally, this function goes by the name of "night mode" or "read mode".

F.lux is revolutionary because it injects a local temporality within the homogeneous flow produced by the digital experience. In this sense, f.lux allows us to customize its rhythm. However, it does little to dent the pervasive culture of overnight work. Rather than actually pushing users to turn off their computer, the notifications about the remaining hours of sleep sent by f.lux can only fuel their sense of guilt. It is no coincidence that college students, for whom sleepless nights are often a default, represent one of the main user group of the app. As it often happens, f.lux offers a technological solution to a broader social issue: it makes us work better at night but, while doing so, it invites us to spend even more time in front of the computer. F.lux brings the night inside the screen because nowadays there is no night without a screen.

Before going to sleep we seek some relaxation between a comment on Facebook and a series on Netflix. So, our devices offer opportunities for leisure as well. But can we really speak of free time? When an increasing number of activities involves the continuous production, consumption and recombination of information mediated by a screen, the boundary between work and non-work, long since blurred, tends to dissolve. When work becomes primarily cognitive, fooling around online makes no exception. Whenever there is a screen, a genuine subtraction from the operational logic of digital media is equivocal. Nevertheless, f.lux brings a bit of humanity in this production mode.

From f.lux twitter account

Published in Italian on Little John Magazine II – 24/7.

Also published on Medium.