Last week I had the chance to attend Reshaping Work, a 2-day conference on the future of work (this year specifically on the platform economy). I’ve been following the event from a distance (read Twitter) for the last two years and I’m glad that I could be there in person this time, as it made me change my mind about it: my first impression was that of a celebratory event in which the platforms could advertise their services without too much criticism. What gave me this impression was an interface issue: all the “research insights” were buried in the 2019 program under a drop-down menu. What I experienced was instead a diverse environment including academics, policy makers, platform-cooperativists, artists, unionists, activists, entrepreneurs, and pseudo-outsiders (like myself).

Meet the Platform Workers session.

In this post I’ll go through some of the talks, panels and installations that I attended and found interesting or useful. This doesn’t mean that this was all, just that for my work and perspective this is what left a mark, also because some sessions were happening at the same time.

I anticipate that this will be a long text so I’m dropping here some of the main keywords that I will touch upon below:

- algorithmic management

- recursive outsourcing

- competing narratives and self-narratives

Jeremias Adams-Prassl Keynote: The Gig Economy in 2020 – 3 Lessons for the Future of Work

Professor of law Jeremias Prassl has recently published a book about the gig economy with a great title: Humans as A Service, which reminds me of a talk by my friend Sebastian Schmieg on “humans as software extensions”. I haven’t read the book yet, but given his keynote I expect a balanced account, neither luddite nor evangelical.

Prassl pointed out that “the future of work” is not singular, that is a iself a contested field with two poles: the optimistic view of liberating entrepreneurship (good for consumers, good for workers) and the pessimistic image of a neo-feudal system of exploitation (powerful intermediaries, controlled insecurity, etc.). According to Prassl, the goal of policy makers is to avoid that neither of these two extremes are reached.

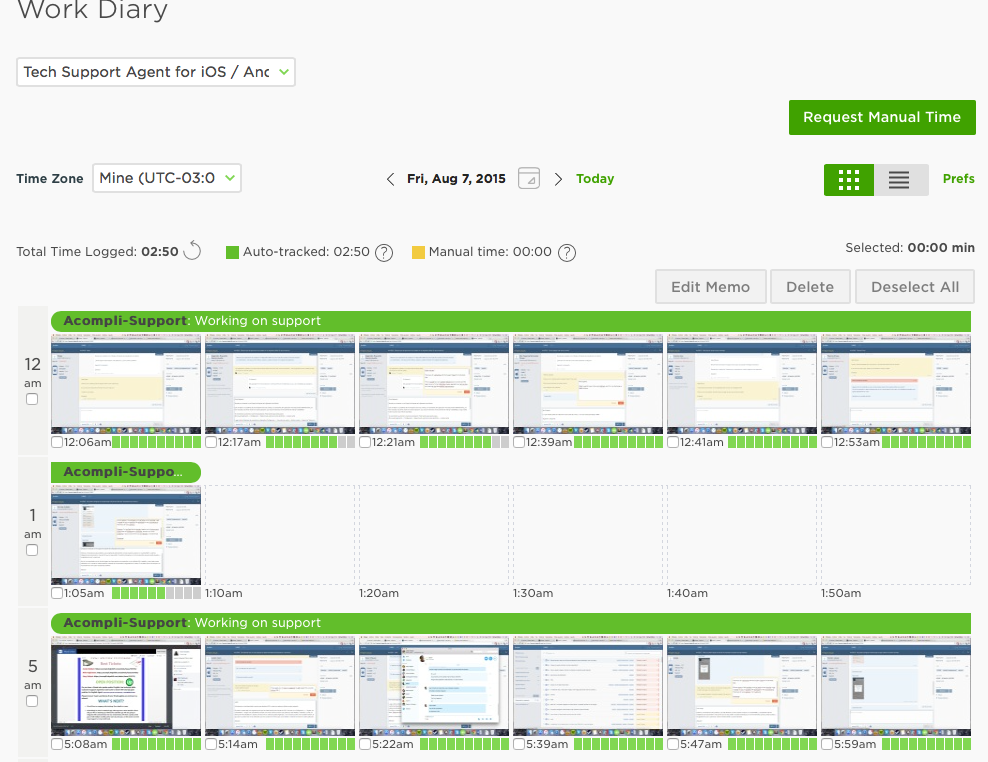

He eplained that not everyone will become a gig worker (currently we speak of 1-3% of the US market) and that the legal tools to define their employment status have been already devised. The new territory is instead that of algorithmic management, which concerns gig workers and traditional employees alike (and we could add also autonomous freelancers, as they employ digital tools to self-manage). Prassl sees many fast developments in this field: “work diaries”, CV screening “predicting employee behaviour” (Minority Report style?), people analitics, and so on. He presented the Humanyze badge and stated that “AI is coming for middle-managers”. But if it’s true that the future is open, I wonder why we have to take these technologies as they are for a given fact.

Upwork’s ‘Work Diary’ interface.

Alina Lupu’s Art Intervention

Before going into the details of Alina’s work, a few thoughts on the very idea of art intervention. In recent years academics have learned to embed artistic research into their events, and this is a good development. But let’s face it, there is always something slightly awkward about it. The fact is that “the art” often functions like a mild entertainment filler between panels and coffees.

I think Reshaping Work’s intervention was better than usual for two reasons: instead of trying to set up a low-budget mini-show with tons of artists in a badly lit room separated from the conference, the organizers went for one single artist and a space that was actually used by people who weren’t necessarily there to experience the art.

Alina Lupu’s intervention.

Alina Lupu installed a series of camera and screens in a library/co-working space where people would be monitored and made aware of the monitoring via a little screen next to each seat and a wall projection. The installation reminds me of earlier works about surveillance and power relationship within the gallery such as Stanza’s one from 2004, using CCTV. However the historical context has changed: surveillance, now called management, has been democratized. As mentioned apropos of Jeremias Prassl’s keynote, not only bosses but platform buyers can now micromanage gig workers by looking at the content of their screens.

Visitors To A Gallery – Referential Self, Embedded by Stanza, 2004 onward.

“Who Cares?” (Wifak Gueddana, Kendra Briken and Miranda Hall)

I particularly appreciated this paper presentation mostly focused on platform-mediated low-income home service work. Wifak Gueddana started by highlighting a problem that is quite common not only in labour studies, but also media studies: platform-centrism. By that we mean the fact that most research is done on the transactional data that is offered or stored by the platforms, which doesn’t tell the full story of the labor relationship. For instance, it doesn’t reflect the fact that often care labor is reoutsourced to a network of families and friends.

Reoutsourcing is one of the aspects I find more crucial about gig economy and remote work: in my book I mention students outsourcing assignments to platform workers, French and Italian citizens subletting their Deliveroo account to illegal migrants, Fiverr sellers using bots to perform the work they get. This is why I curated a entire exhibition on it entitled “Do or Delegate”.

Gueddana pointed out that in this sector women make half of the workforce and if you start looking outside of the platform new stories can be told. For example, one begins realizing that there is a high amount of unremunerated time in gig work (apprently 20 minutes every hour on Mechanical Turk). The researchers compiled a list of more than 60 subreddits dedicated to online work and found out that these spaces can be seen not only as communities “of coping”, but they often function as labor market themselves. A different narrative emerges also in relationship to the isolation of workers and the low pay. And this is something I find crucial as I notice a tendency (especially of news outlets) of victimizing platform workers.

Glovo intermezzo

I sat at a table with Sacha Michaud, co-founder of Glovo. One thing that stayed with me is Glovo’s attempt to intervene on the ethos of some of the markets it’s penetrating. Michaud spoke of “implementing a mentality of saving money” in places like Casablanca. This felt like the US humanitarian missions that people like Ivan Illich were so sorely against. Back in the days, he roared: “to hell with good intentions”. Where are the Illiches of the digital age?

Worker Info Exchange

Another table I joined in was the one chaired by James Farrar, cofounder and director of Worker Info Exchange, a non profit dedicated to “helping workers access and gain insight from data collected from them at work usually by smartphone.” Farrar explained that at first he was a gig economy enthusiast but then, while he was working as Uber driver he was assualted multiple times and the company took weeks to come up with the name of the customer that assaulted him, which is something that should take a couple of seconds for the company. Worker Info Exchange’s rationale is that platform worker rights emerge from digital rights and specifically from access to personal data. If a worker knows that the company is taking decisions about them based on the crossing of these data, the worker can claim that they are not autonomous like an entrepreneur but dependent to the company. In Farrar’s words, “data is the access point to worker rights”.

But what kind of data? Farrar listed 3 “levels” of data collected by the platform:

- green level: basic things like name, address, etc.

- orange: more specific info like a worker’s speed, breaks, ratings, GPS position, etc.

- red: data that come from inference, such categorization, profiling, etc.

Folk Tales of Algorithmic Control (Ana Alacovska, Eliane Bucher and Christian Fieseler)

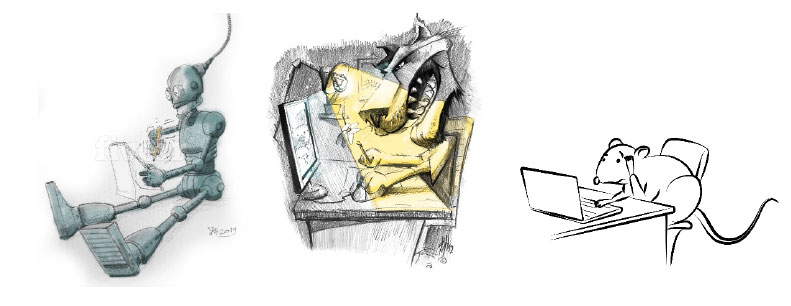

Visual metaphors produced by platform workers.

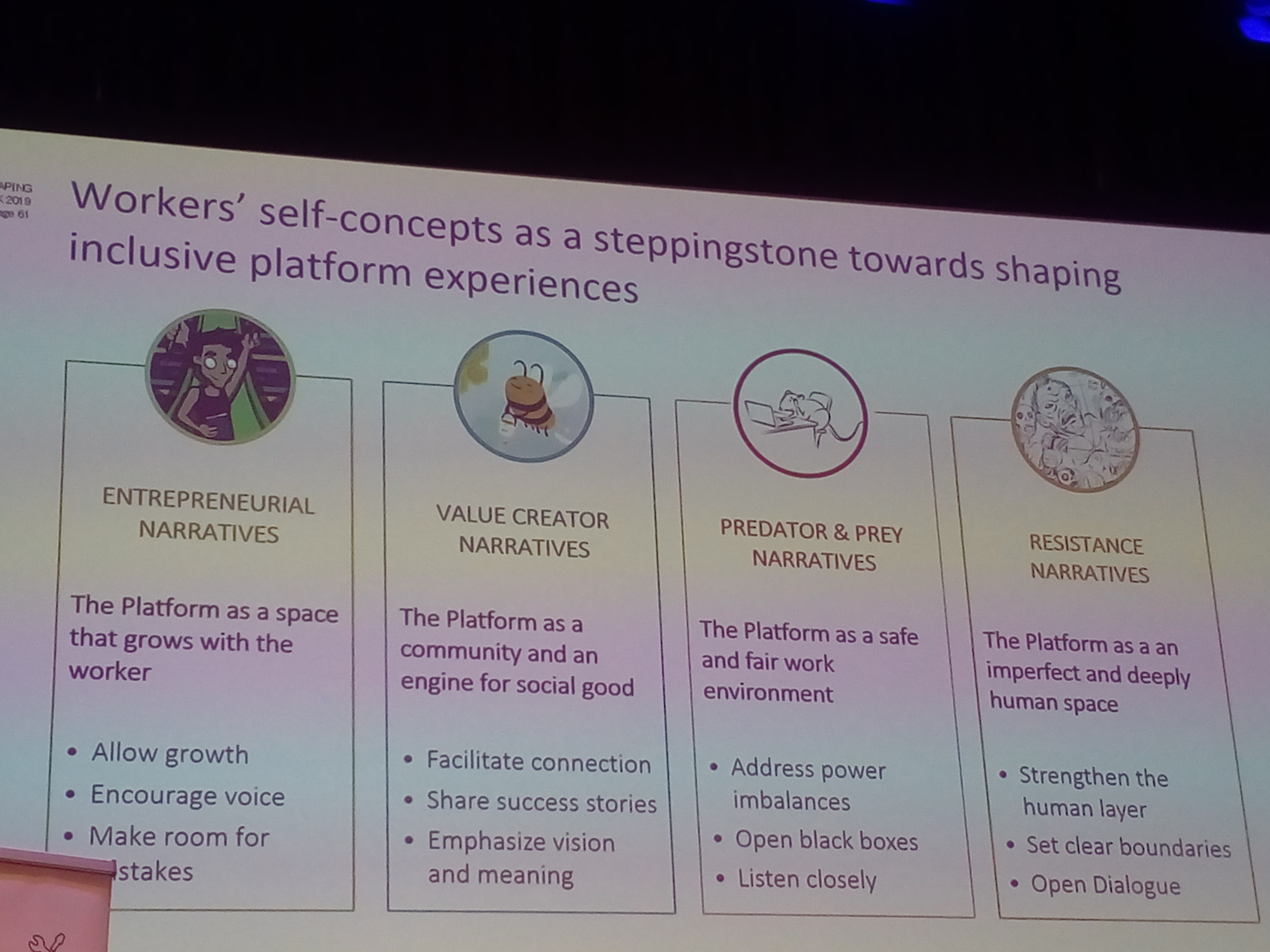

This paper is my personal highlight of the conference and it’s easy to understand why. The researchers started from the premise that creative freelancers are in constant negotiation of their own self-image. Here’s a direct quote from the slides: “in the platform economy, professional self concepts oscillate between self-doubt, cynicism and alienation and bold narratives of flexibility, autonomy and resistance”. So, they decided to hire some illustrators to make a graphic rendition of their own platform freelancing. In this way, they gathered and analyzed 28+ drawings, which were then mapped according to 2 axes: high/low self-agency, distancing/embracing from the work. 4 narratives emerge from the analysis:

- entrepreneurial imagination (high agency, embracing narrative)

- value creation imagination (low agency, embracing narrative)

- predators and prey imaginations (low agency, distancing narrative)

- resistance imaginations (high agency, distancing narrative)

Visual metaphors used to increase platform inclusiveness.

What I find fascinating is first of all the method they used, similar to the one used by artists in several “relational” artworks dealing with gig work. A piece by Tyler Coburn entitled The Warp(2013-14) comes to mind, where he commissioned Mechanical Turks workers to respond to a series of quotes on automation with hand-drawn illustrations. Second of all, I appreciate the researchers’ effort to go beyond a dichotomic understanding of a freelancer’s self-narrative. I think it would be interesting to relate this imaginations to the ones pushed by the plaftorms, which can also be aggressive and based on ideas of resistance (see Fiverr’s one).

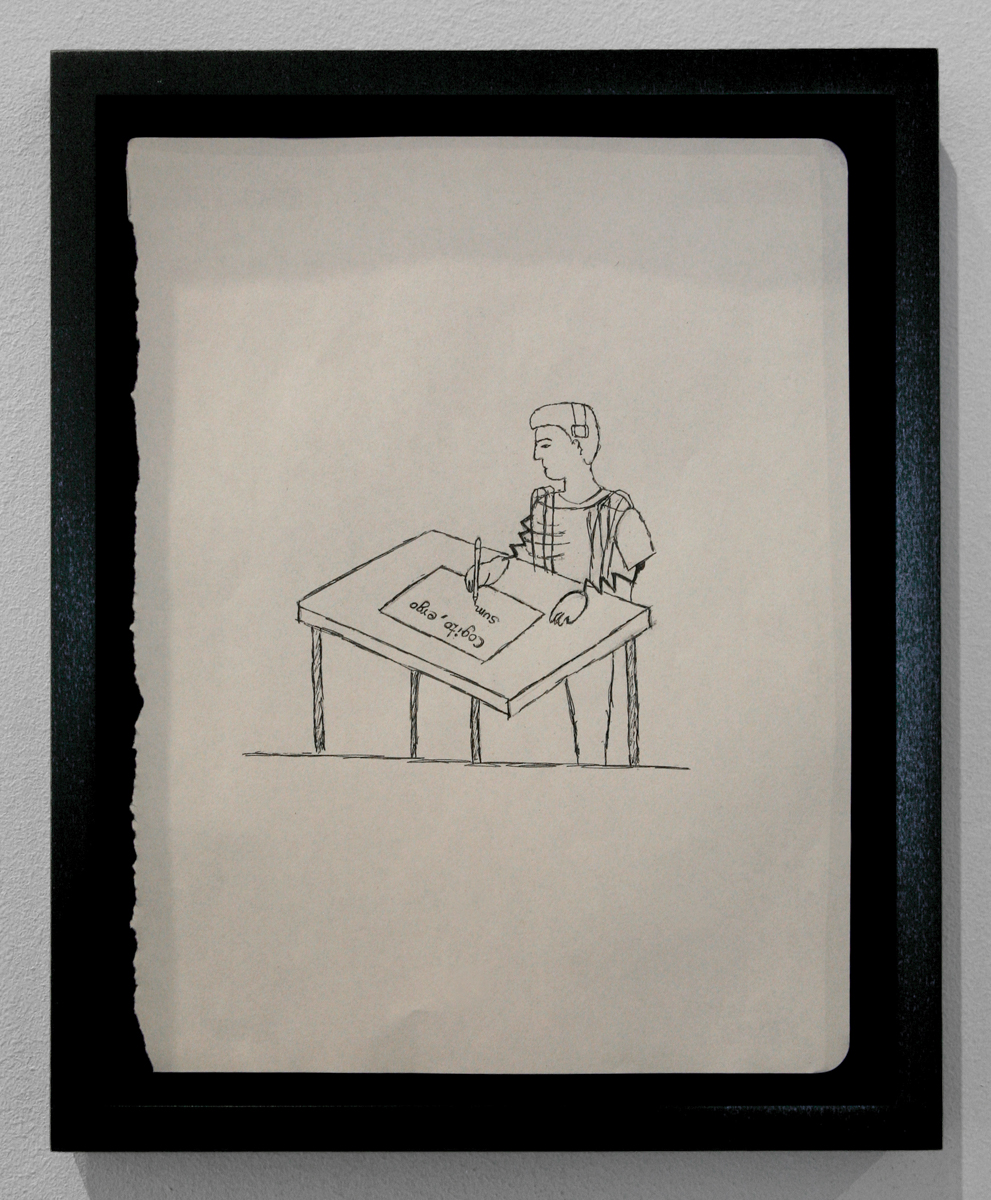

The Warp by Tyler Coburn, 2013-14.

Toptal and Fiverr Platform Workers

As I’ve been following Fiverr for long time, I was really curious about this session. There were two freelancers from Toptal, together with Dean Bosche, Head of Partnerships from Toptal and Falko Kremp, Country Manager Germany of Fiverr. One could say that Toptal is the élite version of Fiverr, as it is an online marketplace focused on the curation and verification of high-end “talent” (they interviewed 1 million freelancers and accepted only 10.000). On the contrary Fiverr has no screening process.

Both Toptal and Fiverr’s presentations were short, as this was meant to be a conversation. Fiverr’s one focused mostly on the training that the platform is offering to the freelancers thorugh a series of on-demand courses developed by other Fiverr freelancers.

Soon after the floor was open to the public the atmosphere became tense. As there was an ambigous idea of geography (it doesn’t matter because there’s an abundance of talent everywhere VS it really matters because of things like health insurance) I asked some information about the global distribution of buyers and sellers: where are the buyers located? Where are the sellers? Where does the money enter the platform from? Where does it go? The answer was generic: obviously the money comes from rich economies and goes to developing ones. Then, given the reaction of the public, I understood that mentioning “the invisible hand of the market” is considered cringe even among lawyers and startuppers. Someone else brought up the “You eat coffee for lunch” campaign, with evident indignation. The response from Kremp was that the company has evolved from that time and now the communication is different (even though the new campaign is also causing a stir).

Crowdsourced Production of AI Training Data (Florian A. Schmidt)

I would like to conclude by briefly mentioning Florian A. Schmidt’s paper on crowdsourcing for AI training, as it shows the urgency of such research. According to Schmidt, the specialized platforms that offer AI training (such as MightyAI) have a Janus Bifrons attitude: on the one hand they present themselves as fully automated and on the other they emphasize their availabilty of quality crowd workers in South American countries like Venezuela. Schmidt alerted us that without any prior notice or explanation MightyAI “fired” 375.000 crowdworkers who suddenly lost their livelihood, as they have been growing dependent on the platforms. This seems to be linked with Adobe cutting off users in Venezuela because of US sanctions. From one day to another these users found themselves unable to access not just their data but their very tools of the trade. This should be seen as a cautionary about cloud computing. For years free software activists have been warning us on the fact that proprietary software lock us in; well, now we have proof that it can also lock us out.

If you enjoyed this report, have a look at the book I just published with Onomatopee: Entreprecariat – Everyone Is an Entrepreneur. Nobody is Safe.