Every year, one or two months before graduation time, I receive invitations from students of various institutions to contribute to their final project with an interview, a podcast, a short text, a talk, etc. Some of these requests derive from projects that are genuinely interesting and related to what I do, while some other requests feel, to be frank, a shot in the dark. But that’s not the point.

The point is that some time ago I stopped accepting most of these invitations directly. The reason is not that I find student projects unworthy of my attention. On the very contrary, I dedicate a lot of my work to the dissemination of theses and projects born in school, sometimes believing in them more than the students themselves. See, for example, the Other Worlds journal, in which I published various excerpts from MA theses; and P-DPA, an archive of experimental publishing, populated by many school projects.

The reason of my embargo is instead structural. Students are encouraged to get in touch with practitioners external to their institutions to get the knowledge, points of view and expertise that they don’t have ‘in house’. If we would live in a society devoid of remunerative issues, there wouldn’t be any problem: exchange is good and necessary. The problem arises when the income of creative practitioners becomes low and intermittent, and academies begin to cut down on staff, both hour- and people-wise.

From the point of view of the student who is working on their final project, a contribution from someone external is a nice gesture justified by the fact that nobody is making money anyway. The urge to write this short text came, in fact, from people working on a project that is “student-initiated and maintained — no profit is being made and no one is making an income.” But there is another perspective to consider: the designer who takes part in the podcast contributes to the ‘buzz’ of the school’s final show, the artist who is interviewed might appear in the academy’s website, the writer who gives a talk at the student-organized panel is bringing visibility and prestige to the institution. From this perspective, these practitioners, enthusiastically invited by students, are doing unpaid work for their schools.

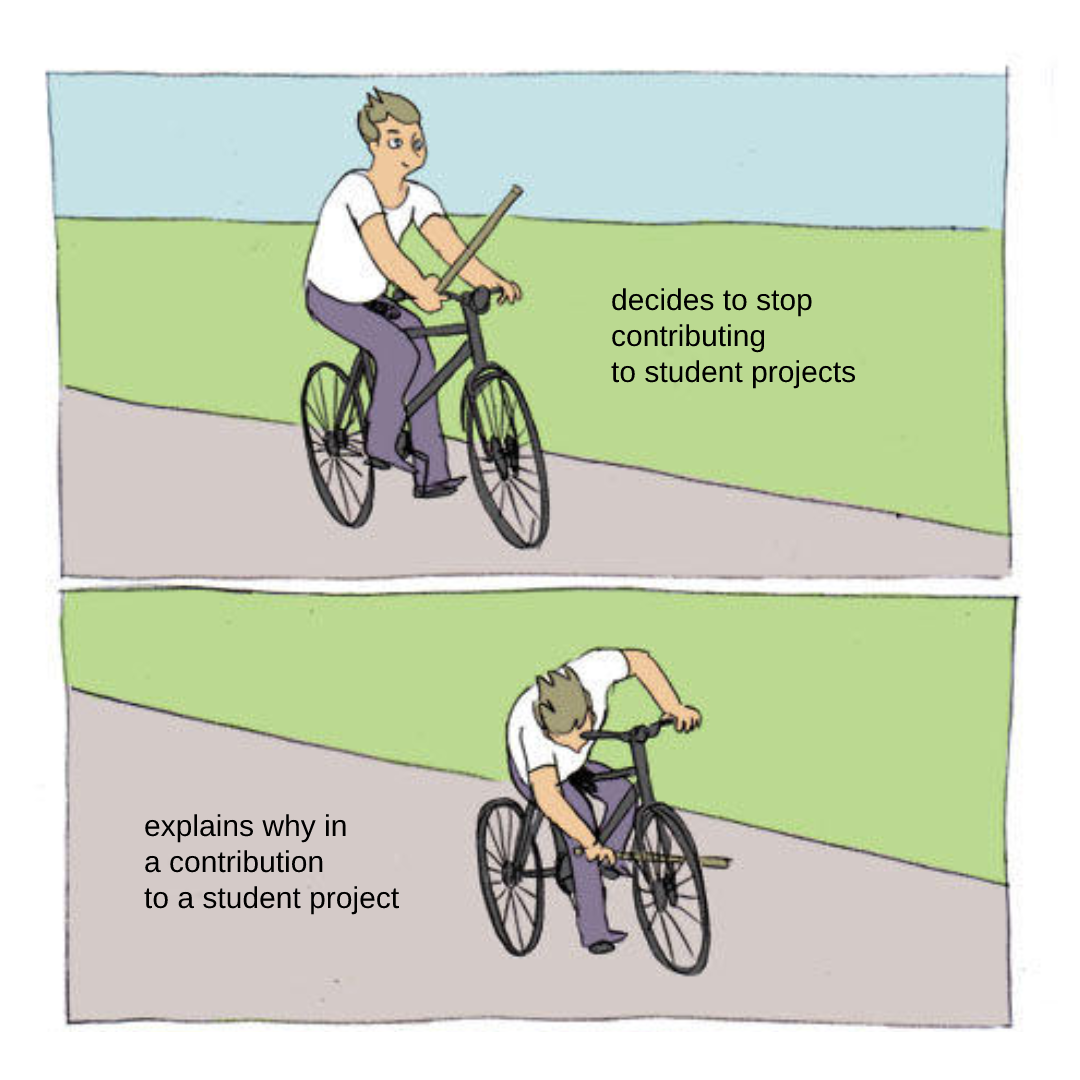

I came to think that carelessly accepting most invitations aggravates this state of affairs, because it hides the fact that while schools expand their reach via the innocent requests of students, their core of knowledge, expertise and culture is shrinking as a result of casualization of staff. One can envision a dystopian institution where there is no actual staff but a growing list of email addresses for students to write to… I’m exaggerating, of course, but I honestly believe that students need to be made aware of this process. This is why I’m writing this.

What to do, then? How to avoid disappointing those students who are genuinely excited about my work? Here’s what I generally do: after thanking the students for their interest, I encourage them to ‘re-route’ their informal invitation, that is, I ask them to ask the school to invite me formally for a talk, a ‘crit’, an article, etc. And you know what? It works, sometimes. This way, I got a few paid gigs as guest tutor, and thanks to that, I could dedicate the necessary attention not only to the project of the inviting student, but also to those of their peers. Needless to say, institutions are often slow, and by the time that a student’s request is approved, they might be already graduated. But there is no harm in trying, and if things seem to take too long, the guest can always decide to proceed informally.

This text was written as a contribution to the project “Structurally Screwed: Political Configurations within Design Education” by Mariana Neves and Urjuan Toosy, Experimental Communication students of the MA Visual Communication at the Royal College of Art.

Also published on Medium.