This is the third post in my Premonition series.

Premonitions are a series of critical foresights by Ruth Les. The scenarios and ideas are concerned with possibilities, not probabilities. ‘…We should not be confined by the probable. We should discover the possibility hidden in the present.’ – Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi

Permission for Pessimism

‘PERMISSION GRANTED. BUT NOT TO DO WHATEVER YOU WANT’

– John Cage

‘Two kinds of pessimism: “The end is near” and “Will this never end?’

― Eugene Thacker

A Premonition for Pessimism

In our emergence from life during COVID-19 we will see new found respect for Pessimist thought. Long thrown from the scene, Pessimist philosophy will be taken seriously, and prior tyrannical ‘positive thinking’ taken in bad taste.

When we all became precarious cognitarians, freelancing our lives away in knowledge work, the abstraction of our worlds was all consuming. Though we were workers, we were not standing in lines of industrial production. What we produced was immaterial, and abstract. The main thread of capitalism’s own evolution is ongoing abstraction. We communicated not offline or face to face, but through abstracted means. The angle of this communication took pronounced ‘positive’ positions. Something Positive is a site set up during the pandemic to present solely positive news about it. Click the button ‘More Positive Vibes’ for continuous hits of feel-good developments; Apple says contractors will be paid during COVID-19 shutdown (Wall Street Journal), or, A rockhopper penguin at Chicago Shedd Aquarium makes unlikely friends with three Beluga whales (The Guardian).

Particularly speaking from experience in the creative industries, to not be explicitly positive was an employment death sentence. In the social scene too, negativity was not allowed. Who wants to hang around with Negative Nelly when you can be with Optimist Oli?

‘Are you a pessimist?” “On my better days…’

–

‘There is no surer sign of pessimism than an overly-optimistic person.’

― Eugene Thacker

‘For the pessimist, nothing is more horrific – or enviable – than happy people, people who seem to go about their lives, blissfully ignorant of all the varieties of doom that inhabit each living moment. Every breath an expiration, every gesture for naught, every birth a crime. Pessimists falsely comfort themselves with the assurance that this awareness is the price one must pay for a higher form of consciousness.’

With the race for financial capitalism grinding to a halt, here we enter a clearing for less abstraction and with it a new acceptance of death. Formerly seen as a ‘negative’ topic, to speak of death is to speak of life. We tasted our mortality, and to ignore this will too be seen in bad taste. To continue with ‘just think positive’ will be a denial of the realities experienced and the real lives lost. In the words of Voltaire, optimism is “a cruel philosophy with a consoling name.”

‘Capitalism has been a fantastic attempt to overcome death.’

– Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi

‘For optimists, the most perplexing question is how one becomes a pessimist – if one is not born one. For the pessimist, the question is how each person, by virtue of being born, is not already a pessimist.’

― Eugene Thacker

Living Pessimist philosopher Eugene Thacker describes pessimism as ‘the introduction of humility to thought’. Now is a time for humility. We got it wrong. We are not immortal. Deal with it. Pessimism can save us from the performance of positivity. Positivity felt abstract; how is one meant to be happy all the time? Our constitution for life as suffering is natural. It is default. To deny this feels unnatural – because it is. We know it is experientially uncomfortable.

‘…as long as the will to life is operative, dissatisfaction arises ceaselessly from within.’

– Nishitani

Pessimist Philosophy Is Not New.

It is found in the Ancient Greeks, and has lived in the philosophical dark side through centuries from Baltasar Gracián to Voltaire, Schoupenhauer, Cioran, and Nietzsche, to today’s Thacker and contemporaries – to give but an condensed, incomplete list.

Philosophical Pessimism is not a mindset nor a psychological disposition. It is a world view. One which “seeks to face up to perceived distasteful realities of the world and eliminate irrational hopes and expectations which may lead to undesirable outcomes.” In Pessimism: Philosophy, Ethic, Spirit (2006), Joshua Foa Dienstag outlines its main propositions, including that human existence is absurd. If COVID-19 taught us anything, it is precisely this.

‘Mostly it is loss which teaches us about the worth of things.’

― Arthur Schopenhauer, Parerga and Paralipomena

“The idea that rational thought would lead to human flourishing can be traced to Socrates and is at the root of most forms of western optimistic philosophies. Pessimism turns the idea on its head; it faults the human freedom to reason as the feature that misaligned humanity from our world and sees it as the root of human unhappiness.” – Dienstag 2009, pp. 33–34

‘And then, it is all one whether he has been happy or miserable; for his life was never anything more than a present moment always vanishing; and now it is over.’

― Arthur Schopenhauer, Studies in Pessimism

Pessimist philosophy is not a mood. As you will gather by the tone of the quotes presented, most pessimists are happy, funny thinkers. Traditional dictionaries suggest something much less nuanced, with a lot less humility.

Here is the Merriam Webster definition of pessimism;

pes·si·mism | \ ˈpe-sə-ˌmi-zəm also ˈpe-zə-

\Definition of pessimism

- an inclination to emphasize adverse aspects, conditions, and possibilities or to expect the worst possible outcome.

- a : the doctrine that reality is essentially evil

b : the doctrine that evil overbalances happiness in life

In our contemporary lives, it is not the presence of pessimism that makes one unhappy. It’s the denial of it.

‘Happiness is the feeling you have just before something goes wrong.’

― Eugene Thacker, Infinite Resignation: On Pessimism

The German philosopher Karl Robert Eduard von Hartmann, who gained much attention from the publication of his Philosophy of the Unconscious (1869) that embroiled him in Germany’s largely forgotten pre-WWI pessimism controversy (pessimismusstreit), asserted that with cultural and technological progress, the world and its inhabitants will reach a state in which they will voluntarily embrace nothingness.

Nothingness, perhaps.

Futility, maybe (“Futility is the most difficult thing in the world”, Cioran).

Resignation, more likely.

With new resign, let’s lead over resign as rebellion.

Resign as Rebellion

Albert Camus indicated that the common responses to the absurdity of life are often: Suicide, a leap of faith, or rebellion. If we anticipate a mass state of resignation, we could interpret it as a revolution of passivity. This is how it looks when subjectivity implodes.

Resign. The most subversive of slogans. Anti-productivity, anti-‘progress’. When there is nothing more to do, let’s not do it. Everything has reduced – pollution, traffic, internal energies. The Slacker as an archetype takes centre stage. No longer an emblem of laziness, this is a figure of rebellion. Here is the post-work society we were hoping for, though entirely different than we expected it to be. Imposed. Enforced.

Anti-Capitalist poster: “I didn’t go to work today”, America (1987)

“Tame birds sing of freedom. Wild birds fly” – John Lennon. German Left revolutionary merch.

Welcoming in Slackerdom

We are all Homer Simpson now. We all can be Homer. Except, can we? Do you still have the capability? Is it still a possibility for you to do nothing, to idle? Can you hold still or is the agitation all-consuming and no longer a choice? The archetype of the Slacker may have become a fragment of our imagination, just another remnant of the past. Josh Cohen describes the slacker as somebody “who turns an aversion to the real world and its demands into a concrete ethos and lifestyle”. I dream of becoming a slacker. I long to be able to lay back and opt out. ‘Going offline’ is the daydream. Being hyper-connected is the reality. It’s beyond a cognitive decision.

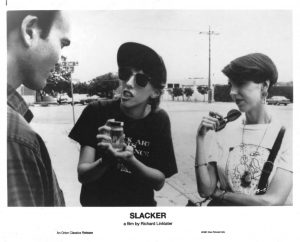

In one of his scandalous inversions of received wisdom, Oscar Wilde suggested that action was the real refuge of “people who have nothing whatsoever to do”. “To do nothing at all,” he adds, “is the most difficult thing in the world,” because it deprives us of the easy evasions of busyness and purpose. In Richard Linklater’s 1991 film Slacker, comprised of weird ‘baton-passing’ episodes of random slackers from the subcultures of Austin, Texas – amateur metaphysicians, tinkerers, dreamers, petty criminals, anarchists and poseurs – linked only by their uncompromising renunciation of “the kind of work you have to do to earn a living”, the viewer takes a trip through slackerdom in these lives living away from measurement of value against externally imposed targets and achievements. Linklater’s characters present a smorgasbord of vivid antitheses to our neoliberal, endlessly entrepreneurial selves. Slacker gives a glimpse of what Roland Barthes called “idiorrhythmy”, “where each subject lives according to his own rhythm”. To live life as a slacker means to “refuse the regimentation of time and space by the impersonal forces of work and leisure, giving yourself over to the pace and style of the impulses, curiosities and desires unique to you” (Cohen). Say hello to a new social ideal, whereby the rhythms of all our individual lives co-exist without encroaching on each other. Can we say goodbye to the 24/7 temporality of online life: follow, like, update, upload, link and (of course) buy.

Still from Linklater’s ‘Slacker’ (1991)

By offering perspectives on issues such as the Puritan work ethic, work-incited self-importance, leisure versus idleness and human relationships, Linklater joined the preceding generations of slackers, providing a much needed balance to the American obsession with work and success.

– Małecka, Katarzyna. (2015). In Praise of Slacking: Richard Linklater’s Slacker as a Hallmark of 1990s American Independent Cinema Counterculture.

‘I dwell in Possibility – / A fairer House than Prose – / More numerous of Windows – / Superior – for Doors –’

– Emily Dickinson

If the symbol of content resignation is the Slacker, what does that make for the Rebel? Perhaps we go down a branch in the Simpson family tree to Bart. Bart Simpson the symbol of original 80’s rebellion – with the mantra once feared by the parents in American homes ‘Underachiever, and proud of it man’. Do we all quit trying to be Type A and take on living as Type B? Trying less. Caring less. Doing less.

Bart Simpson graphic, part of the Great Simpsons Apparel Ban across American elementary schools during the 1990’s

“If we allow our whole selves to be absorbed by the demands and agendas of a persecutory to-do list scribbled by others, we will quickly lose the very dimension of life that makes it worth living.”

– Josh Cohen, Not Working (2019)

The New Revolt is a passive one. Sit back and relax. Find pleasure. Rediscover joy. The world as we know it is dismantling and rejigging,

and you don’t need to lift a finger.