‘What are we to make of someone who says they love their work and cannot imagine doing anything they enjoy more, yet earn so little that they can never take a holiday, let alone afford insurance or a pension? How are we to think about a person who is passionate about the creative work they do up to 80 hours per week yet feel fearful that they will not be able to have the children they long for because of the time and money pressures they face?’ – Rosalind Gill in Technobohemians or the New Cybertariat? (2009)

A long decade later, Rosalind Gill’s questions are as relevant today as the day she formulated them. To work in the Dutch cultural sector must be objectively awful. In 2019, artists earned an average gross income of 18,340 euros per year. That is just over half of the income of a garbage collector and 28 times less than that of a top executive at Royal Dutch Airlines (bonuses excluded). Moreover, cultural work is as unstable as it is badly paid. Half of the people in the cultural sector work as freelancers and in the visual arts, this is even 80%, which means that their income is as unstable as it is low. These freelancers and flex workers have a poor bargaining position, are often not insured against occupational disability, have a low pension accrual, and a high risk of unemployment. In 2016, after extensive research, the Dutch Council for Culture and the Social and Economic Council concluded that ‘the labor market situation in the cultural sector is worrying’. An understatement if ever there was one.

Things didn’t exactly get better with the advent of corona. As soon as the crisis set in, the costs of freelance workers proved to be the simplest cutbacks for institutions. In the third quarter of 2020, self-employed artists had an unprecedented loss of revenue of almost 70% on average compared to the previous year.

Platform BK and Yuri Veerman, ‘For Our Heroes’, 2020. On the Malieveld in The Hague, ten heroes appeared. Each on their own pedestal, but some a bit higher than the others. Thus, Platform BK posed the question: How much money does a hero earn?

And yet. Artists stayed motivated, kept on working, kept on creating. The cultural production of museums and presentation institutions continues to flourish despite all the forced closures – online, on the street, or with other innovative solutions. It is often even assumed that there is a causal relationship between these facts, that creativity equals the ability to survive with little financial means. Artists and cultural workers supposedly use their creativity to develop creative revenue models; they independently make something out of nothing. However, I read the opposite in the above facts. Creativity is a means to continue producing, despite persistent precarity and underpayment. As an individual quick-fix for a collective problem (the lack of subsistence security), creativity hides the structural nature of precarity rather than remedying it.

This is not to say that the cultural sector is the only one structurally struggling with livelihood insecurity. For years there have been society-wide calls to reduce precarity, create more security for the self-employed, better contracts, and an end to pseudo-self-employment. In 2018, the Borstlap Commission was established by the national government to investigate the state of affairs across the Dutch labor market. The conclusion Hans Borstlap presented in 2020 was loud and clear: ‘The rules around work are no longer sustainable.’ Three decades of deregulation, austerity and government downsizing have led not to healthy competition and profit maximization, but to the erosion of social security. Borstlap concluded that flex work and (false) self-employment must be reduced by reintroducing permanent contracts as the norm. It is debatable whether a return to the old labor market model of permanent contracts for everyone is the solution is open to question. However, it is clear is that neoliberal ideas about the labor market – the more deregulation the better, and a small government that lets the market do its work – have lost their legitimacy.

The cultural sector plays an important role as an example when it comes to looking for alternatives to the current labor market. For decades, the cultural sector has led the way in making the labor market more flexible, with by far the highest percentage of self-employed workers. But if cultural workers were the first, the fastest, and the most flexible, can they also be the first to move beyond the current precarious situation? What happens if the artists and freelance workers, who are the backbone of the cultural sector, simply refuse to live on a pittance any longer – collectively?

The Rise and Fall of Social Art Policies in the Netherlands

To understand the contemporary context of the precarity issue, we need to go back to the period just after 1945, when the welfare state was built. In addition to the introduction of general health care, welfare for the unemployed and the state pension for the elderly, and scholarships for students, artists were also well served in the new social contract. Under pressure from the Professional Association of Visual Artists, the Ministry of Social Affairs rolled out the Contraprestati Scheme in 1949, which was replaced in 1956 by the famous BKR (Visual Artists Scheme). Under both of these schemes, artists could claim an income from the government in exchange for a quid pro quo. This generally meant: a benefit in exchange for art. In this way, artists had a stable basic income, and municipalities and the government built up a collection of many hundreds of thousands of works of art.

Over the years, more and more artists went ‘into the BKR’ – more than 5,700 in total. As a result, the costs of the scheme became sky-high and municipalities and the state didn’t know what to do with all the art anymore. Therefore, the BKR was made more restrictive in 1972, put out of action altogether in 1987, and officially repealed in 1992. Artists could now ‘just’ claim welfare and from there find their way into the labor market. At least, that was the idea. In practice, however, this did not really happen and municipalities tolerated artists on social assistance without them having to apply for it. In view of this ‘difficult link’ between artistry and the labor market, it was decided in 1999 to again provide income support of 70% of the social security level for a maximum of four years per decade. This was regulated in the WIK (Wet Inkomensvoorziening Kunstenaars), which was transformed in 2005 into the WWIK (Wet Werk en Inkomen Kunstenaars).

The idea behind this succession of regulations can be traced back to a combination of social income policy and the Enlightenment idea that art elevates the people – that civilization exists by the grace of art and that art must be given the freedom of autonomy to be able to fulfill the social objective of elevation. However, it is also clear that the arrangements became increasingly minimal and restrictive. The simple reason for this was the out-of-control practical and financial burdens. But the political climate also changed and criticism in the public debate swelled, making the status of art as a public good less and less obvious.

Increasingly, criticism was directed at the exceptional status of artists and the major role of public institutions in the arts. In 1997 Riki Simons wrote De gijzeling van de beeldende kunst (The Entrapment of the Visual Arts), an indictment of the publicly funded cultural system. According to Simons, the government was far too meddlesome in keeping cultural temples afloat with public money and scientists erected high thresholds around those temples. Thus the state, with the help of science, would have ‘monopolized away’ any private initiative. Sven Lütticken, in a review of this book, immediately remarked that Simons’s ideas about the oppressed blessings of the market are rather romantic. Were private investors really eager to sponsor culture but not given a chance to do so by the government? 25 years and a number of major cutbacks later, we can conclude: no, private initiatives do not simply jump into the hole left by the government.

For that matter, the role of private money in the arts has certainly grown in recent decades, as Pieter van Os and Arjen Ribbens show in their recent book Tussen kunst en cash (Between Art and Cash). However, not in the romantic way that Simons had in mind. In thirteen revealing chapters, the two NRC journalists show the growing, corrupting influence of big money on the Dutch visual arts. Scams, conflicts of interest, and damaging misunderstandings are becoming more and more common, and art itself is also suffering. The fact that 150 to 200 ultra-rich people are breaking one auction record after another is leading to a category of art market art (Koons, Hirst, Basquiat) that has come into vogue and is controlled by a handful of major gallerists. Even for wealthy collectors with some critical ability, these kinds of overpriced dots, color fields, and metal balloons are totally uninteresting, Ribbens and Van Os show.

At the beginning of this century, however, that realization had not yet sunk in, and the call for tough but necessary cuts, ‘realism’ and entrepreneurship was increasingly heard even within the institutional art world. In the publication, Second Opinion: Over beeldende kunstsubsidie in Nederland (2007), published jointly by Fonds BKVB, the Mondriaan Foundation, and NAi Publishers, a wide range of important critics of the Dutch subsidy system are given a chance to express their views. The starting point for this publication was ‘that the subsidy policy in the Netherlands promotes mediocre rather than good art, that Dutch art lacks real urgency and that the system maintains an enclave that has placed itself outside of reality and the public’. Furthermore, according to the editors, ‘subsidies seem to focus too much on supply (artist support) and too little on promoting demand (institutions, audience)’. To top it off, they suggest that ‘subsidies, despite their well-intentioned efforts, are ultimately counterproductive’. In a review of this book, Pascal Gielen concluded that the subsidy system had been found to be too democratic, making quality control impossible. You would almost wonder which idiot ever thought of setting up a social-cultural subsidy policy.

Into the Creative Industries

This erosion of public appreciation reached an all-time low about ten years ago. During the first Rutte administration (2010-2012) the Dutch tradition of culture and income policy was definitively overturned. Spurred on by the credit crisis, Secretary of State for Culture Halbe Zijlstra (VVD) was given the task of implementing a massive cutback of 200 million euros on the budget for culture.

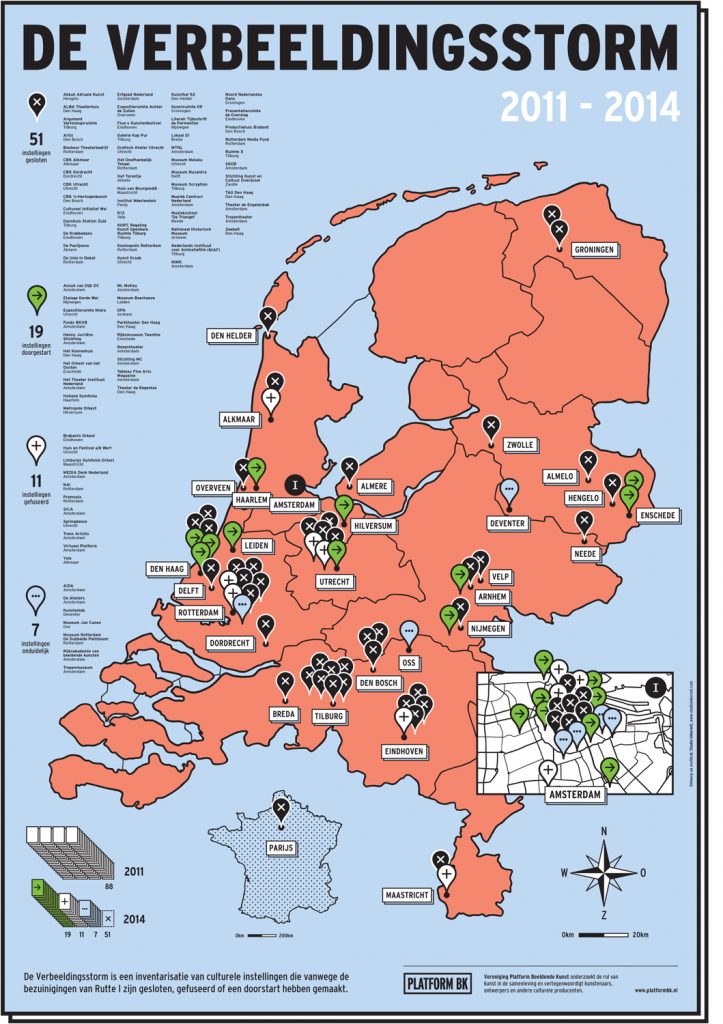

Zijlstra enthusiastically applied himself to the demolition work. A painful detail in this story was that the State Secretary claimed not to know anything about art and culture. He saw this as an advantage: the broom had to be run through the sector and feelings of sympathy would only get in the way. No sooner said than done. An inventory by Platform BK shows that 51 cultural institutions were forced to close their doors, 11 merged and 19 barely made a start.

Platform BK, ‘De Verbeeldingsstorm’ (Storm of Imagination), 2014. Graphic design: Studio Inherent.

And, yes, the Work and Income Act was also abolished by Zijlstra in 2012. Thus, decades of crumbling social prestige culminated in a mass cutback that was symptomatic of the almost complete denial of the intrinsic and social value of the arts.

Naturally, the outcry over these cuts was great and it didn’t take long for the cultural sector to take action. During the Cry for Culture, cultural workers and sympathizers gathered in noisy rallies throughout the country, literally calling for the preservation of culture budgets – and thus culture itself. In retrospect, this expression of collective anger, unfortunately, proved counterproductive. For skeptics, the images on TV once more confirmed the idea of cultural workers as a group of loud-mouthed and spoiled leftist hobbyists. It is safe to say that cultural workers are still suffering from the image damage caused by Rutte and Zijlstra.

The fact that the intrinsic appreciation of art and culture had sunk to an all-time low meant that the focus was increasingly on the instrumental value of culture. Culture as a means to provide social and economic issues with a creative solution. A lucrative sector focused on entertainment, impact, and innovation. The most obvious consequence of this instrumental thinking was the rise of the Creative Industry in the Netherlands. Diversification, participation, the art of impact, and cultural entrepreneurship were presented as the fresh wind that the stagnant cultural field needed. The subsidy system was overhauled, giving birth to the Stimuleringsfonds Creatieve Industrie. Moreover, the creative industry was declared a top sector in the new top sector policy. This paved the way for a wide variety of innovative cultural practices, in which anything was possible, as long as it included enough creative entrepreneurship, digitization, design thinking, 21st-century skills, and social impact. In short: the Netherlands went in search of a for-profit cultural sector, the possibility of which the United Kingdom had already demonstrated in the 1990s under Blair.

Critics immediately recognized the small funds dedicated to retraining and impact generation as a palliative with a neoliberal agenda. For imagine: in this austerity drive (which affects not only the arts but all social services) you lay off all the occupational therapists in a local care home. Nice cost savings, but the elderly still need daycare. Then of course it is very nice if two artists in a ‘creative’ and ‘inventive’ way want to do the work that was first done by five care professionals. See here: the social impact of art in the participation society.

Incremental Revaluations

The situation has not changed substantially since then. However, a gradual turnaround can be observed. In recent months, for example, a true renaissance of the Visual Arts Regulation has begun, spurred on by two exhibitions and a catalog denouncing the negative image of the BKR under the title ‘Een monument voor de BKR‘ (a monument to the BKR). According to the exhibition makers and collection managers, it is thanks to this regulation that the national collection has works by Karel Appel, Corneille, Jan Dibbets, Marlene Dumas, Daan van Golden, Lucebert, Jan Wolkers, and Theo Wolvecamp. Apparently, the arrangement that seemed to arouse chagrin in everyone was in the offing long enough for romanticization to set in. Nous Faes astutely observes that it is not so much the social side of the BKR that can count on revaluation, but mainly the valuable works of art that are in the supposed wastepaper basket of the government depots.

Yet this revaluation of the BKR is exemplary of a slow turnaround in both public debate and cultural policy. An important impetus for this turnaround was the publication of the aforementioned report Passion Valued by the Council for Culture and Social and Economic Council in 2016. The councils jointly took a close look at the cultural labor market and their findings were not miserable: structural underpayment, lack of security, excessive flex work, you name it. A reality that had long been known to artists and cultural workers was now recognized in policy terms. In response, the Ministry of Education, Culture, and Science had the Labor Market Agenda for the Cultural and Creative Sector 2017-2023 drawn up with 21 recommendations to achieve a better functioning labor market.

Four years on, the outcomes of this process are significant. With the establishment of Platform ACCT, the cultural sector has an official, sector-wide labor market consultative body – hopefully paving the way for the development of the Collective Labor Agreement the sector has lacked thus far. Three codes were also drawn up in response to the aforementioned Labour Market Agenda: the Diversity and Inclusion Code, the Code Good Governance, and the Fair Practice Code. In the field, the codes are widely acclaimed as a ‘moral collective agreement’ and jointly supported value system. Moreover, the Fair Practice Code includes compliance with the Guideline on Artists’ Fees developed by the field, giving the field a clear and institutionally credible means of combating underpayment. The icing on the cake of this policy trend is the embracing of the codes by culture minister Van Engelshoven as a condition for subsidies from the national culture funds. Cultural institutions can no longer get any government funding, without, for instance, paying artists a fair fee or accounting for their accessibility.

New Autonomy or Old Precarity?

Despite the gradual revaluation of cultural work after 2012, it is safe to say that the social role of the arts has changed radically over the past half-century: from part of the welfare state that was valued on cultural-social grounds to lucrative sector focused on entertainment, impact, and innovation.

Yet the notion of artistic autonomy has stuck. Artists are very fond of the freedom to engage in the artistic process, to think critically, to make beautiful things, to hold up a mirror to society. You can justifiably make the simple statement: without freedom no art. In conversations about art – in museums, at academies, and at kitchen tables – concepts such as autonomy, intrinsic value and ‘art for art’s sake’ often come up.

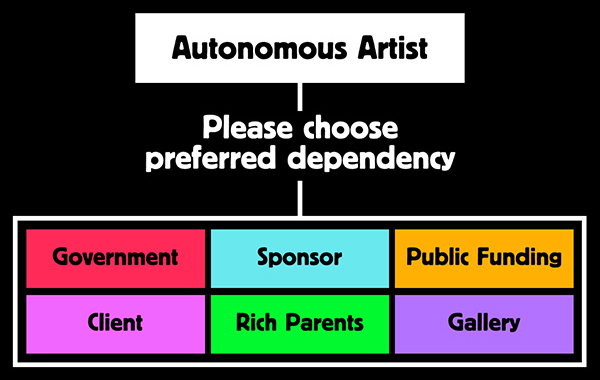

However, though it is still in use, the transformation of the role of art has also transformed the notion of autonomy. That is, the term ‘autonomy’ has lingered, but has gradually been endowed with a new meaning and a new social function. Whereas artistic autonomy in the welfare state meant a privileged position facilitated by the state and based on intrinsic-social appreciation, the term now implies rather a game of rejection from and attraction to the market.

Take arts (scientific) education. To this day, many art schools and humanities faculties resist the sucking power of liberalization. Efficiency, professional competence, and market-oriented thinking are distrusted there. So, autonomy, its historical and theoretical antithesis, remains enticing. Teachers don’t want to direct their students’ practice too much or ruin it with talk of sales, marketing, or negotiating positions. And students are often fine with accepting an existence just above the poverty line in exchange for freedom. But when they graduate after about five years, they will still have to enter the market, with a degree in hand but no job prospects. That’s a reality check that will leave most wondering whether they have been trained as critically thinking and socially responsible individuals, or as creative entrepreneurs.

Yuri Veerman, ‘Autonomous artist, choose your dependency’.

Some persist in their meager autonomous existence. According to them, you do not become an artist because of financial gain, but because of the pursuit of your dream or even to fulfill your vocation. This is what Hans Abbing in his book Why Are Artists Poor? calls the ‘art ethos’. References to Picasso, who in his young Paris years shared a single bed with a roommate and therefore alternated between sleeping one night and painting through the night, are obvious. The art ethos holds that poverty is proof of the real deal. You’re only really an artist if you’re willing to put up with being poor.

But a growing group of young creatives has a different point of view. The flexible and critical thinking that makes them so creative and the fact that they don’t want to sit still makes them extremely enterprising. They see opportunities, they want to take the initiative. They find their way – sometimes easily, sometimes with great difficulty – on the market. Precarious but free, they live from gig to gig, hopping between side jobs and cheap studios. Their precarious existence is embellished by silver laptops, inspiration posters, impressive internships, self-help books, chai lattes, productivity apps, a portfolio of 128 pages, and other outward displays of cultural entrepreneurship. In addition, these young generations of entrants into the cultural sector are trying to shape their own lives with the resources they have: staying positive, seeing solutions, developing innovative business models. They might still try to find their way into public institutions and funding bodies, but also experiment with crypto, crowdfunding, and corporate assignments.

Thanks to this focus on freedom, flexibility, and self-reliance, the difference between precarious work and self-employment gradually blurs until it eventually becomes imperceptible. Thus, these cultural workers are initiated into the ‘entreprecariat’ of the creative industry, to use Silvio Lorusso’s apt term. This is also the core of what autonomy means in the neoliberal sense: dogmatically staying positive, thinking in solutions, business models, and innovations, with the inexhaustible belief that one will manage to make it alone. Some more or less random examples (mostly non-fictional):

- Letting visitors to your festival mine bitcoin for half an hour to earn their entry ticket

- Raising money through Voordekunst to publish a book (important: have the book printed on ecologically responsible paper made from tomato plants)

- Creating art for market art of UHNWI (note: this model requires a fair amount of flattery and luck)

- Providing food art at conferences

- Drawing mangas on Twitch

- Making a documentary about social design, paid for with donations and the sale of sustainable merchandise

- Selling subscriptions on Patreon to see animated art films

- Turning Delft blue punk graffiti into decorations for Hema, Schiphol, or the NS

- Design virtual fashion (note: keep the print run limited with an eye on exclusivity)

- Sending newsletters via Substack about the joys of going offline

- Selling artist books at an independent art book fair

- Selling digital cocktails in the bar of your livestream

- Popular these days: encrypting net art with a non-fungible token and earning a little extra via the blockchain

Sam (Simpsons Artist), ‘Animator’, from the Creative Workers series.

This creative entrepreneurship is closer to the ‘high’ arts than may at first appear. Artists have a reputation for being side hustlers. A side job as a teacher at an academy, in the hospitality industry, or as a house painter is quite common. With the rise of the creative industries, so-called hybrid practices have become further normalized. By being an artist and programmer at the same time, or a graphic designer and advertiser, or a researcher and copywriter, cultural workers are accommodating for their own autonomy.

There is nothing wrong with trying your luck in the creative industry, or with making a good living (it happens). But we cannot ignore the fact that individual declarations of autonomy in the creative industries of our ‘participation society’ often come down to dependence on the market, with the artist in practice often being happy to work for a platform and a pittance. In the fusion of autonomy and entrepreneurship, the art ethos – thought dead in the creative industries – plays up again: one has to make sacrifices to be able to do one’s ‘dream job’.

This transformation means that autonomy has become the responsibility of the individual, financially as well as intrinsically. It is permissible to keep an autonomous, non-lucrative practice, as long as in addition one also participates in society in a productive way. A serious problem here is that an individualized notion of independence or autonomy plays into the hands of managerial instrumentalization. A self-regulating sector, where people take care of each other in perfect harmony with the market (read: where cultural workers divide their poverty among themselves), is right up the alley of a neoliberal manager.

For a concrete example, we can think of the way in which Minister van Engelshoven (D66) made compliance with the Fair Practice Code in the cultural sector mandatory in 2020. She summoned subsidized cultural institutions to start paying fair wages and fees but did not release a budget for the additional costs involved. For the activists who had been fighting for years for the right to fair labor relations and payments, this was a victory with a bitter aftertaste. Several politicians and experts noted that we cannot expect institutions to continue programming at the same level while paying artists better, without extra money. The cultural sector itself united and called on the Minister during a Solidarity evening in ITA to put her money where her mouth is. Van Engelshoven kindly but resolutely ignored this advice. Her comment: ‘The principle is: implement and explain.’ So, in the first instance, it was really up to the sector itself to divide up its poverty among itself. Smaller institutions, in particular, were faced with a devilish dilemma: should they pay artists adequately at the expense of their own staff, or should they cut back on their programming and thereby jeopardize their reach (read: public legitimacy)?

From Autonomy to Post-Precarity

At the moment, these traditional and neoliberal perspectives on autonomy coexist. It is difficult to say which of the two is more problematic. The neoliberal idea of autonomy negates precisely the crucial principle that made traditional autonomy a reality: that a public mission deserves public funding. But also reverting to the idea that artists are creators or saviors of civilization and therefore deserve autonomy is not a credible alternative (anymore). Social support for this is now too small and is becoming increasingly smaller. Therefore, in countering precarity, let’s store the haughty ideas of independence or autonomy in the archive box for American Dreams.

Instead, it is more interesting to look at practices and actions that take an effective step in countering precarity from the contemporary context. Fortunately, there are plenty of examples: from decentralized distribution of resources via self-organized galleries and bread funds to coops, collective negotiations, codes, and other solidarity structures. By taking (economic) action but ignoring creative entrepreneurship, these practices lay a concrete claim on the social system and offer a glimpse of a future beyond precarity. Another set of examples:

- In 2016, Wok The Rock and Casco in Utrecht organized the Parasite Lottery, combining the existing lottery model with arisan, a commons-oriented micro-credit system popular in Indonesia.

- The same Casco is part of the Arts Collaboratory, an international network of art institutions and collectives that manages a common pot of money as an alternative to the repetitive circus of fund requests.

- The Rotterdam platform De Kunstambassade was set up by artists to maintain visibility in times of Covid. One-fifth of the proceeds from work sold through The Art Embassy is divided equally among member artists.

- There is a trend to address pressing issues in the art sector with solidarity fundraisers, such as the sale of Dead Darlings for the ailing W139, or the benefit F-RAZZOR for survivors of sexual violence.

- In April 2020, Groningen ‘culture giants’ decided to make a collective gesture to the artists and self-employed workers in the cultural sector. With a sum of 170,000 euros, which they received from corona support packages, they opened a quick-window for artists and theater-makers who individually fell by the wayside.

- Since 2006, bread funds have made their appearance in the Netherlands, as a safety net in the event of illness and as an affordable alternative to AOV for freelancers. There are now more than 700 bread funds in the Netherlands, with more than 27,000 participants, many of whom work in the cultural sector. Initiatives like the Dutch CommonEasy and German Circles – A Basic Income on the Blockchain seek to expand upon this concept of income sharing.

- As house prices continue to skyrocket and social housing becomes more inaccessible, more and more artists and creatives are opting for cooperatively managed properties with (a combination of) studios, housing, or presentation areas. Good examples are Tetterode and Bajesdorp in Amsterdam, Maakhaven in The Hague, Leo XIII in Tilburg and Motel Spatie in Arnhem (RIP).

- Platform ACCT has developed a Whitepaper Collective Bargaining for Independent Professionals.

- The previously discussed Artists’ Fees Guideline, developed by BKNL, also contributes to the collective bargaining position.

- Pictoright Fund manages the image rights of affiliated image-makers and thus provides a more or less fixed source of income for artists, photographers, illustrators, and professional associations.

- Finally, the good old art library, with standard rates that are attractive to both artists and renters, deserves to be mentioned in this context.

By taking action but ignoring creative entrepreneurship, these initiatives lay a concrete claim to the social systems of our society and offer a glimpse of a future beyond precarity. However, it is hard to generalize these practices. Both solidarity and supplementary sources of income come in many sorts and shapes – maybe as many as there are individual art practices. On the other hand, it is precisely this diversity of complementary incomes, rules, and solidarity structures that is potentially successful in combating precarity. Instead of formulating a singular post-precarious labor model, to discern three unifying principles among the diversity of practical initiatives.

PRINCIPLE 1: INCOME = BASIC INCOME + SUPPLEMENTARY INCOME

To eliminate precarity, a more stable and secure income position for the self-employed is necessary. This can be achieved both through self-organizing experiments with earning power and by enforcing better policies and more subsidies. Both are necessary, yet are insufficient by themselves. Complete focus on self-employment leads to the dominance of market forces, leaving no room for the valuation of non-financial (social or cultural) value. Too much reliance on government regulation and subsidy, however, leads to passivity and damages the reputation of the arts.

It is therefore important to make a clear distinction between the right to a basic income (more precisely, the right not to live in poverty) on the one hand and the experiment with supplementary income on the other. The right to a fair, fixed income that creates a basis for livelihood security is a matter that must be regulated through laws and regulations from the government. Experiments with generating and redistributing supplementary income, or with the mutual spreading of costs and risks, are pre-eminently the domain of self-organization. Therefore, both the political demand for basic income and active experimentation with earning power are preconditions for achieving post-precarity. As long as this distinction remains clear, it is possible to develop solidarity-based forms of income redistribution that do not lapse into the redistribution of poverty.

The call for a Universal Basic Income, which is heard within the arts with some regularity, is not a radical idea, by the way. It is often shot down as an unattainable dreamscape, but the Tijdelijke Ondersteuning Zelfstandig Ondernemers (TOZO), effectively a basic income provided by the Dutch government to the self-employed during the corona crisis, is a nice preview that shows what is possible with enough political will. Thus, Rutte III’s policy unintentionally seamlessly joined the Dutch tradition of culture and income policy that had been expertly killed by Halbe Zijlstra during Rutte I.

Institute of Radical Imagination, statement 11 from the Art for UBI Manifesto.

PRINCIPLE 2: SOLIDARITY = BOTTOM-UP SOLIDARITY + TOP-DOWN SOLIDARITY

The struggle of cultural workers for a basic income has another major advantage. This idea does not claim an exceptional position for the arts but develops a vision for a large, society-wide solution to precarity. After all, basic income applies just as much to shelf-clerks, teachers, doctors, and bank managers. Thus, the idea of basic income demonstrates solidarity that extends beyond the art world.

This is precisely the main characteristic of solidarity: it goes beyond individual interests. It does not place culture in an exceptional position but connects it to society. The years of collaboration between artist Matthijs de Bruijne and FNV Schoonmakers; the Solidarity Sessions in W139, where the struggle for justice in the arts was linked to the rights of residents without EU passports, refugees, and cleaners; X-Y Action Fund, a bottom-up fund for culture and activism that supports actions such as Dit Zijn Onze Helden, but also a climate alarm and campaign against domestic violence in Pakistan; Extinction Rebellion’s bike ride for culture; the slogan ‘Art = Solidarity’, which sounded during protests in Flanders and Brussels against the sharp cuts in the culture budget in November 2019; the discussions about the necessity of solidarity in and with culture in the corona crisis, which were held by directors and art bosses in Amsterdam, Rotterdam, and Utrecht, among others.

Matthijs de Bruijne, ‘Migrant Domestic Workers FNV Demonstration: 100.000 Families Trust Us’, 2013.

This connecting solidarity forms the second principle for post-precarity. By actively declaring solidarity, solidarity unites individuals or individual organizations on the basis of conviction and puts the precarious effect of competition and self-interest to rest. With solidarity, we can, in Quincy Gario’s words, ‘ensure that we are not pitted against each other to fight for crumbs – caused by an ideologically driven scarcity’.

This raises the question of what exactly to expect from solidarity. What is it that makes people commit to each other in solidarity? How long does solidarity last before self-interest gains the upper hand again? In short: what can you achieve with solidarity today?

In the lecture ‘Reinventing Solidarity‘, Joram Kraaijeveld pointed out that the concept of solidarity in the 21st century can be accused of being vague. A clear class distinction is missing in our society, so solidarity does not simply coincide with class struggle. Instead, today you can show solidarity with

KOZP groups, artists in Flanders, teachers, Greta Thunberg, Zapatistas, people from Palestine, and so on. Trade unions call us to solidarity with workers; political parties used to call for solidarity with the poor; and the Embassy of the North Sea calls for solidarity with all dead and living matter in and of the North Sea.

Kraaijeveld attributes this vagueness not to a flawed value system, but to the erosion of social solidarity structures by austerity and privatization since the 1980s. The previously discussed reduction of social services for artists is an example, but the privatization of education, health care, legal aid, and public transport are just as much. The neoliberal project has systematically dismantled the solidarity structures that brought about a self-evident inclusion in the welfare state.

To counteract this ‘desolidarization’ and to reinvent solidarity, two strategies are crucial, according to Kraaijeveld: resistance and defiance. Resistance against the further erosion of institutional solidarity structures, such as social housing and social security. And resistance through the self-organizing development of new solidarity structures, such as bread funds and housing cooperatives.

Kraaijeveld’s argument leads to a ‘continuous reinvention of solidarity’ along two lines: bottom-up and top-down solidarity. This distinction probably resonates with the experience of anyone who has ever done activist work. For social change, solidarity and self-organizing activism from below as inspiration, crowbar, or influencing the social discussion is necessary. For small and self-organizing interventions – if with sufficient strategic vision and tactical ingenuity – can have an impact on the political choices that will determine our future. The fact remains, however, that to realize fundamental but sustainable change, it is necessary that political choices are made – and translated into rules, laws, and (financial) possibilities. Solidarity from below and from above is therefore not so much opposed as complementary. It only becomes really exciting and effective when a bridge is built between the two.

PRINCIPLE 3: ART NEEDS RULES TO BE FREE

Art is a sanctuary where perception is broadened, power is questioned, and new worlds are opened up. The functions of pushing boundaries, breaking rules, and taboos are an integral part of art’s freedom. However, it is becoming increasingly clear that maintaining art as a sanctuary requires tight rules in the art world.

This is not surprising. We all understand, for example, that judges must be able to judge independently and freely, but that this is subject to very strict conditions. Artists have a different social role, but in a certain sense, the same applies. The cultural labor market, the art market, and art education need clear rules to guarantee the freedom of art.

This goes against intuition. Pushing boundaries and breaking rules and taboos are functions that are often attributed precisely to the critical tasks of art and culture. But it is important to note here that liberalization is next to austerity and is characterized by deregulation. A ‘deregulating’ effect of art and culture can therefore simply reinforce the disruptive effect of neoliberalism. Taking matters into one’s own hands, demanding rules, and making proposals for them, has much more emancipatory power in the neoliberal era than, for example, kicking against sacred cows.

This certainly applies to the labor market. The problems of excessive flexibilization have already been discussed above. In addition, a large part of the cultural sector is not defined by the size of the demand, but by the supply – there are, after all, many artists and cultural workers. As a result, one cannot rely on the ‘natural’ process of price setting through the interplay of supply and demand; instead, clear frameworks are needed for minimum wages and employment conditions, such as the Guideline for Artists Fees.

The need for clear rules has also become painfully clear in art and cultural education in recent times. In this case, it is mainly about determining pedagogical preconditions, drawing up codes of conduct, and caring for students. The institutional moral compass was conspicuous by its absence in the reports on Julian A. and Martijn N. A ‘disconcerting report‘ appeared about the Design Academy, exposing abuse of power, misconduct, and threats. Instagram pages like @calloutdutchartinstitutions, @artgoss and @no.more.later are full of harrowing stories about academies all over the Netherlands. And the handling of students in the corona crisis, who pay thousands of euros a year for inferior, online education, is also firmly under fire.

Meme from @no.more.later

Again, there are misconceptions about the freedom of the arts, which have been translated into mostly outdated didactic views. In an article for Mister Motley, Judith Boessen sharply counters a series of myths that haunt professional art education: that ‘real’ artists are brilliant men and women are best suited as muses; that great pressure leads to excellence; that good artists automatically make good teachers; that students must be demolished before they can be built up; that boundaries are there to be broken; that the art world is simply hard and competitive and so are art schools. Study after study shows that it is not pressure and uncertainty, but security and clear goals that lead to the best educational outcomes. It is time for this basic insight to be better and more structurally translated into art education.

From Principles to a New Future

Once again, the three principles for post-precarity are: 1.) distinguishing between basic and supplementary income, 2.) continuously reinventing solidarity, and 3.) protecting the freedom of art and culture with clear rules. These principles have been extracted from the present and past, with the idea that they will be valid in the future. However, that remains a big, exciting question – the focus of Our Creative Reset. Where might these principles lead in the future? Where are the big issues, obstacles, and opportunities? I conclude

A long march through the institutions awaits in the area of labor market regulation. Who will represent cultural workers after the death of the trade union? What initiatives are there? How do they unite? What can they achieve and what cannot? Are new forms of associations, networks, platforms emerging that are equipped for the policy table of the future?

How will arts and cultural education evolve? Can academies and schools succeed in creating a safe environment with sufficient attention to professional competencies, without sacrificing artistic freedom? If so, how? Will art school teachers finally get decent contracts? Can the anger and criticism of students be taken to heart? And will academies be brave enough to allow the politicization of institutional space?

Having societal discussions at the national level is important, but when viewed properly, it is also a fringe activity. Most political and economic decisions that determine the situation in the Netherlands are now taken at the international level, in Brussels. What is the future of European cultural policy, the new Bauhaus, the Erasmus programs? Will there be a European minimum wage? Is a European solidarity network of cultural workers emerging? And what would be the goals of such a network?

How will crypto, blockchain, and NFTs function after the hype? Will they become or remain interesting sources of supplementary income? How can we be pragmatic, tactical, and at the same time critical in this area? Where is the space between solutionism and fear of new technology? How can cultural workers use this digital reality to empower themselves?

Which of the many experiments in solidarity-based income redistribution have the greatest potential? And how can these be further developed? Can we imagine a souped-up bread fund? A cooperative resurrection of the art lending business? An alliance of institutions that only makes collective fund requests and redistributes on the basis of trust? What will it take to engage in this kind of high-level experiment? Who will do it? Where? When?

For an overview of all literature used for this piece, and more, see: https://networkcultures.org/ourcreativereset/resources/

This text is a reworked translation of a Dutch essay. Find the original text here: https://networkcultures.org/longform/2021/06/03/post-precariteit/