We’re lucky that Sean Dockray, the founder of the Public School, is a participant in the Digital Enclosures Workshop at the Unbound Book Conference and is also is giving a lecture on Monday 23 May (venue TBD) in Amsterdam about his open text archive Aaaaarg.org and other interventions. For Mute Magazine, he recently spoke to theorist Matthew Fuller about the behaviour of text and bibliophiles in a text-circulation network. From the site:

We met to discuss the growing phenomenon of text-sharing. Aaaaarg.org has developed over the last few years as a crucial site for the sharing and discussion of texts drawn from cultural theory, politics, philosophy, art and related areas. Part of this discussion is about the circulation of texts, scanned and uploaded to other sites that it provides links to. Since participants in The Public School often draw from the uploads to form readers or anthologies for specific classes or events series, this project provides a useful perspective from which to talk about the nature of text in the present era.

Here is an excerpt:

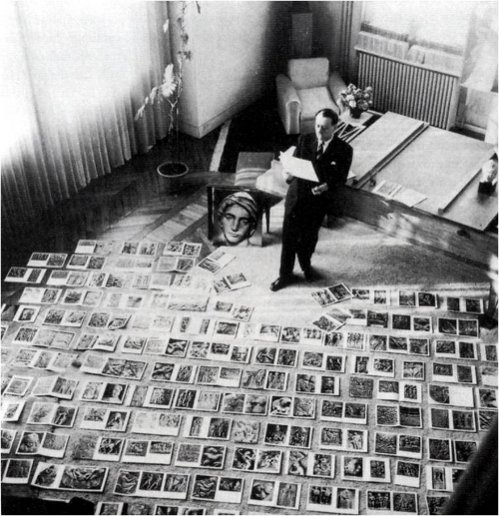

MF: I want to follow that kind of strand of habits of accumulation, sorting, deferring and so on. I wonder, what is a kind of characteristic or unusual reading behavior? For instance are there people who download the entire list? Or do you see people being relatively selective? How does the mania of the net, with this constant churning of data, map over to forms of bibliomania?

SD: Well, in Aaaaarg it’s again very specific. Anecdotally again, I have heard from people how much they download and sometimes they’re very selective, they just see something that’s interesting and download it, other times they download everything and occasionally I hear about this mania of mirroring the whole site. What I mean about being specific to Aaaaarg is that a lot of the mania isn’t driven by just the need to have everything; it’s driven by the acknowledgement that the source is going to disappear at some point. That sense of impending disappearance is always there, so I think that drives a lot of people to download everything because, you know, it’s happened a couple times where it’s just gone down or moved or something like that.

MF: It’s true, it feels like something that is there even for a few weeks or a few months. By a sheer fluke it could last another year, who knows.

SD: It’s a different kind of mania, and usually we get lost in this thinking that people need to possess everything but there is this weird preservation instinct that people have, which is slightly different. The dominant sensibility of Aaaaarg at the beginning was the highly partial and subjective nature to the contents and that is something I would want to preserve, which is why I never thought it to be particularly exciting to have lots of high quality metadata – it doesn’t have the publication date, it doesn’t have all the great metadata that say Amazon might provide. The system is pretty dismal in that way, but I don’t mind that so much. I read something on the Internet which said it was like being in the porn section of a video store with all black text on white labels, it was an absolutely beautiful way of describing it. Originally Aaaaarg was about trading just those particular moments in a text that really struck you as important, that you wanted other people to read so it would be very short, definitely partial, it wasn’t a completist project, although some people maybe treat it in that way now. They treat it as a thing that wants to devour everything. That’s definitely not the way that I have seen it.

MF: And it’s so idiosyncratic I mean, you know it’s certainly possible that it could be read in a canonical mode, you can see that there’s that tendency there, of the core of Adorno or Agamben, to take the a’s for instance. But of the more contemporary stuff it’s very varied, that’s what’s nice about it as well. Alongside all the stuff that has a very long-term existence, like historical books that may be over a hundred years old, what turns up there is often unexpected, but certainly not random or uninterpretable.

Image: French art historian André Malraux lays out his Musée Imaginaire, 1947

SD: It’s interesting to think a little bit about what people choose to upload, because it’s not easy to upload something. It takes a good deal of time to scan a book. I mean obviously some things are uploaded which are, have always been, digital. (I wrote something about this recently about the scan and the export – the scan being something that comes out of a labour in relationship to an object, to the book, and the export is something where the whole life of the text has sort of been digital from production to circulation and reception). I happen to think of Aaaaarg in the realm of the scan and the bootleg. When someone actually scans something they’re potentially spending hours because they’re doing the work on the book they’re doing something with software, they’re uploading.

MF: Aaaarg hasn’t introduced file quality thresholds either.

SD: No, definitely not. Where would that go?