We are happy to announce that our first-ever Unlike Us reader is set to be printed in January 2013. The reader will cover a facet of social media topics, from activism to theory to decentralization. While we are wrapping up the publication, please enjoy the following guest post by Paul Sulzycki, with his thoughts on ‘walled garden’ vs. decentralized social networks.

Breaking down the walls, or how social networking ought to be.

by Paul Sulzycki

Some history

I’ve been on the periphery of the social networking world since deleting my Facebook account three years ago, quietly waiting for a federated option to rise up and shed light on how horrible all our current privatized social networks are. This brief article will concisely wrap up what I’ve found while waiting for The Next Big Thing, and then go into what hopes I have for the future. A caveat first: I know next to nothing about coding and am writing purely from a user experience point of view.

Figure 1: This is the problem with the Internet today. On a favourite site I frequently visit, this is what greets me on the home page. Really? It’s 2012 and the Internet is still fragmented among a few key applications with wonky privacy laws and questionable security practices? Come on now.

The problem

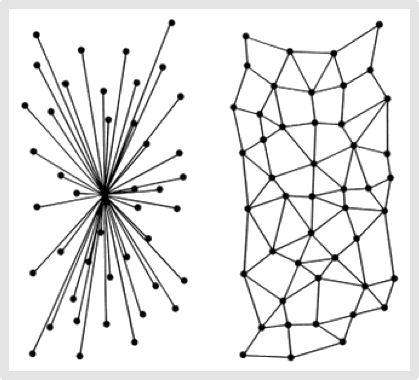

Figure 2: Users on centralized networks must all communicate through one source (L). Users on decentralized networks can communicate directly with each other (R).

Big networks like Facebook, Google+, and Twitter are what are called “walled gardens”. That is to say, in order to use them you must be on them. This is in stark contrast to “open garden” communications like phone, email, or even the Internet: you don’t have to be with the same service provider to contact a friend who might be with another provider. Though tougher to control on the administrative side, this sort of relationship is ideal for users. For one, it makes customer profiling much more difficult for big corporations. Secondly, it means that you can switch providers and still plug into the network. Lastly, it protects users in sensitive circumstances like journalists or activists whose entire network might be compromised if relying solely on walled garden systems.

Social networking really is a valuable tool. Since Facebook’s launch almost a decade ago, it has turned into something of the next step up in electronic communications. Making social networking even better—and safer—rests on the idea of opening social networks up so that members can communicate across platforms. This concept is known as decentralization/distribution/federation.A second fix to the system would be easy account downloading and deletion. Imagine how great it would be if you could carry a backup of your entire social network (contacts, conversations, albums) on a USB key, and could re-upload it with any social network provider you wanted. Account portability of this sort is still quite a ways away, but social network decentralization and inter-/intra-network federation is already happening all around us. Below are the stories of three of the biggest current trailblazers in this field.

DIASPORA*

Immediately after hammering the last nail in my Facebook account I started looking for alternatives. I loved networking socially and I sure as heck wasn’t about to become an e-hermit. I quickly got word of an interesting project based out of the States: four undergrads from NYU had heard a motivational talk by a Columbia prof, had raised $200,000 on Kickstarter, and were set to revolutionize the internet with their decentralized network. “Great!” I thought. “Sign me up!”

Right from the get-go, things were rocky. Communication from the core developers was scarce and unclear. No one knew where to sign up, for example. Many of us in the first experimental wave playing with Diaspora now know there are different “pods” and that accounts on these pods communicate with each other in a federated environment, but this still remains a point of confusion for newbies—especially for those coming in fresh from a walled garden with a centralized provider.

Poor communication aside, group chats happened over IRC, coders got together the world over to contribute, and the project quickly gained momentum. Sure, the promise of getting the project to a usable beta stage by the end of 2010 seemed a bit outlandish, but the community was still filled with hope. When the project continued in a buggy alpha mode well into 2011, only the more experienced users started raising concerns. In retrospect, listening to them would have been a smart move for anyone who went gung-ho in promoting Diaspora as a Facebook killer.

Things only got worse on the communication front by 2012. Features would appear and then disappear, all without explanation. Popular, much-requested modifications would be shot down for no apparent reason, while useless changes would often show up and confuse everyone. There was much talk about having chat working on the Diaspora platform (even video chat), but this thought—like so many before it—came and went without any serious development.

But all this was peripheral: Diaspora was working. It was buggy and came bundled with lots of social disputes between the higher-ups, but it worked. It was decentralized, you could go in there and grab the code, pop it onto your own server and presto! You were off. You’d then plug in to the greater Diaspora ecosystem where you could interact with the free-thinking, privacy-aware, security-sensitive, technically-savvy crowd ~350,000 strong. Many of them were (and still remain) the creative types who actively contribute to conversations. You know, the “conversation flow directors”. Diaspora also brought in many fresh features: being able to format your posts through markdown formatting, the ability to subscribe and “follow” hashtags in posts, and even a rudimentary RSS feed built right into your home page. All these bright innovations certainly made the network a vibrant place to call home.

It was about 1½ years into playing with Diaspora that I noticed the project take a turn to resemble Tumblr more and more, moving its emphasis away from providing a solution to the “Facebook problem”. Interesting applications like Cubbi.es were written up that allowed you to neatly Shift+click over an image anywhere on the net and pull it into your Diaspora stream, immediately sharing it with all your contacts. Sadly, this project—again, like many things on Diaspora—was never maintained and is now obsolete.

Fast-forward to now: the Diaspora team has officially stated they are moving away from Diaspora to work on a new, marginally-related project, “Makr.io”. I’ve been on there once or twice and it looks to be something like Tumblr. You can edit posts from the community, mostly through basic picture modifications like adding captions, borders, etc. I sadly realized that Diaspora might actually never deliver on its promises and breathed a quiet prayer of thanks that I hadn’t gone full out promoting the network to every stranger I met.

~Friendica

I “met” Mike Macgirvin on Diaspora, where his posts quickly showed him to be a quiet, tech-minded fellow who had quite a bit of experience in computers. A short while into being on Diaspora, and after seeing how unreceptive its core developers were to his suggestions for improvement, he went off and did his own thing.

Thanks to this bold move, we have arguably the best social networking alternative that actually does what Diaspora promised: you can communicate from Friendica to all of the major social networks out there. It’s also fully federated, and its onus isn’t so much on providing support to servers holding very many user accounts—as Diaspora had started doing before departing on their Makr.io experiment—but more so on providing people with tools to connect with each other from wherever they want, ideally spread out across as many servers as possible. In fact, it’s not uncommon to see registration for some of the original, more popular Friendica pods closed so the developers can focus on providing quality service and not quantity. We all know servers cost money and Friendica, unlike Diaspora, is completely run on free time and small, private contributions—not even remotely comparable to Diaspora’s $200K kick-start.

Hold it. I know what you’re thinking. “This is it! Why aren’t we all just using Friendica?”

For one simple reason: the user interface is pretty bleak. Going on there, you feel you’re back in the early days of the web, trying to navigate one of those classy geocities sites (minus the GIFs). As I mentioned at the beginning of this piece, I am not particularly gifted in advanced technical matters but those who are tend to swear by Friendica. User interface remains a big thing for me, however, and Friendica’s interface is just too ugly and difficult to operate.

Friendica fans are quick to point out that UI isn’t everything. Perhaps it would be best to close this section with a quote by Mike, the man behind the movement:

“‘Social networking’ is a business model from 2005. ‘Social networks’ are obsolete. I want to get rid of them. I want to break down their silly little walls and open the Internet so people can communicate with their friends without requiring a U.S. owned corporation to act as a go-between. Communicating with people is not a business model. It’s what we do—and it’s what the Internet was designed for. Not selling stuff. That came later, and screwed up everything.

“We don’t need to agree to let people spy on our email. Why do we think that we have to accept people spying on our other online conversations—and claiming ownership of all our thoughts and photos?

“What I’m building is a free internet without walls—and where people can share with their friends and not have to ‘sell their soul to the devil’ to do so. It may look a bit like a social network but it is much more than that. It is freedom.”

This, in a nutshell, is my hope for social networking as well.

Friendica Red

Mike has most recently departed from Friendica to work on a new project: “Red”. As it looks now, Red will be where Mike will put to use everything he’s learned from Friendica, along with four major upgrades:

- Taking into consideration the friendship continuum that our social lives revolve in (not everyone is always either a friend or non-friend).

- Dissolving the assumption that only geeks are capable of running servers with social networks.

- Building mobility into the system so you can access your account using a USB drive through any device and through any Red server in the world.

- Fixing the aforementioned UI design problems.

Libertree

There is one other network out there that is more underground than most. Libertree was started by a Diaspora user who only geos by the handle “Pistos”. Pistos was an early helper with Diaspora who wrote lots of code for it, much of which never was integrated for one of those weird reasons mentioned earlier. Tired of this approach, Pistos forked the project, downloading and ameliorating the Diaspora source code with neat features like group pages and chat; items that Diaspora users had requested but that had never been implemented while the core developer team continued focusing on making their product look shinier.

Seeing Diaspora’s core developers weren’t overly cooperative, Pistos closed his fork and started Libertree. Libertree currently serves a tiny community, but the advances it presents are truly stunning. They have made some really neat UI advances (you can toggle notifications!) and the community, being so small, votes and provides very much input regarding feature requests, bugs, and even bug fixes.

Where does this leave us?

At the beginning of something new; I can confidently say that. The disgruntled rumblings becoming more and more apparent on the Internet show that people don’t enjoy our current model of communication; of always having to go through third-party corporations to get a private message to a close friend. Who knows how many times our behaviour is being recorded, analyzed, and stored. And who knows what this information is being used for? The thought of this alone makes me quite uncomfortable.

In a perfect world, I would like to have a social network that was easy to install so I could run it on a small server in my house, serving close friends and family. Institutions would also have their own servers with their own social networks for members (schools, companies, teams, projects, cities… the list goes on), and all networks would be able to fully communicate with each other. Features like email, chat, video chat, group pages, photo and video albums and easy link-sharing plugins would be a must with these new systems. Cory Doctorow presents a great point in Shannon’s Law (2011): “The Net’s secret weapon is that it doesn’t care what kind of medium it runs over.” Breaking down all our walled gardens is a start in capitalizing on this truth.

What will I be doing until then? Hanging out on Diaspora, all the while keeping a close eye on both Libertree and Friendica Red. These networks attract the activists, conspiracy theorists, geeks, artists, and all the other creative types who don’t follow the crowd. This alone makes these networks a healthy place to check out for conversation and to see what’s happening around the world.

However, the moment a network arises that looks as good as Diaspora, and that makes good on Diaspora’s initial promises (federation, decentralization, privacy, security, and account portability), I’m making the jump. Again. Hopefully this time for longer.