Please complete the following sentence: I am…

How many different responses can you come up with and, more importantly, what do they say about you? In 1954, Manfred Kuhn and Thomas McPartland developed the twenty statements test, an influential instrument used to measure self concept. The test requires respondents to complete the sentence “I am…” on twenty occasions, with the resulting statements serving to indicate prominent identity markers. I may be a dancer, socialist, vegetarian and Harlem Shaker, all of which inform my overall sense of self.

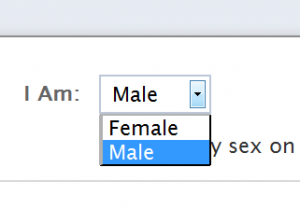

So who am I on Facebook? Traditionally, the social media giant has required all new users to complete the ‘I am’ field with a binary gender position: I am female or I am male, and apparently nothing more.

This changed last week, however, and new Facebookers are now required to select ‘Female’ or ‘Male’ without the preceding ‘I am’ assertion and underlying identity implications. But while some may feel this marks a step in the right direction, the fact that gender choice is both binary and mandatory means we are still essentially being defined on the basis of ‘what’s in our pants’.

It wasn’t always like this. In the formative years of Facebook, the ‘select one’ instruction situated above its corresponding ‘female’ and ‘male’ categories could itself be selected, providing an alternative option for gender identification. As a result of this selection, the news feed of the site employed fairly inelegant gender-neutral pronouns when referring to the user: ‘Sam Samson commented on their own status’ or, even more awkwardly, ‘Sam Samson has tagged themself in a photo’. Such grammatical dubiousness was only further compounded when the website went global, with translations proving virtually impossible for languages in which gender marking on singular pronouns is obligatory. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the brains at Facebook confronted these obstacles by enforcing a strict binary construction of gender. ‘Please select either Male or Female’ is the polite yet inflexible instruction provided to new users who neglect to fill the sexually dimorphic field today.

This stuff matters. As Andrew McNicol explains in his Unlike Us Reader article, None of Your Business?, “because these social media profiles act as a mediator between us and others, the more value we ascribe to these public faces of our complex selves the more likely we are to internalize the identity restrictions set by the system.“ In other words, the gender limitations imposed on us by Facebook’s interface can simplify our understanding of ourselves in life away from the screen, diminishing the pliability of identity construction.

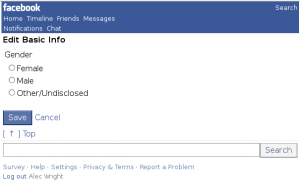

Enter Alec Wright, the engineering student who recently developed an automated method to once again remove gender from Facebook. In three reasonably straightforward steps, users can now change their gender status to ‘other/undisclosed’, which is reflected through the site’s use of gender-neutral pronouns. While this may not present a perfect fix to the gendering issues that Facebook entails, it certainly affords a little more freedom of identity expression for the user.

If Sam Samson is interested in Wright’s brilliant JavaScript, ‘they’ should probably head here. If Sam Samson is interested in social media in general, ‘they’ should definitely head to Unlike Us #3, which is scheduled to take place in just over a week!