Creative and community projects turn to crowdfunding as a promising model of financing. The hype around this movement is generated by success stories of projects raising hundreds of thousands of euros, as well as the growing number of crowdfunding platforms on a local and international level.

Nevertheless, building a successful campaign can be as challenging and time consuming as applying at an other type of funds, whether private or public. While one form of guidance exists on some crowd-funding platforms, it’s mostly as ‘tips and tricks’ to make it happen. Some platforms publish statistics, but in a de-contextualized matter, where no opportunity for useful interpretation is made possible. Most commonly it’s about the total amount raised by all projects, or the total amount of funders – nor particularly helpful for the next crowdfunder.

An essential element that is missing is therefore a different insight in the dynamics of the crowd-funding platforms.

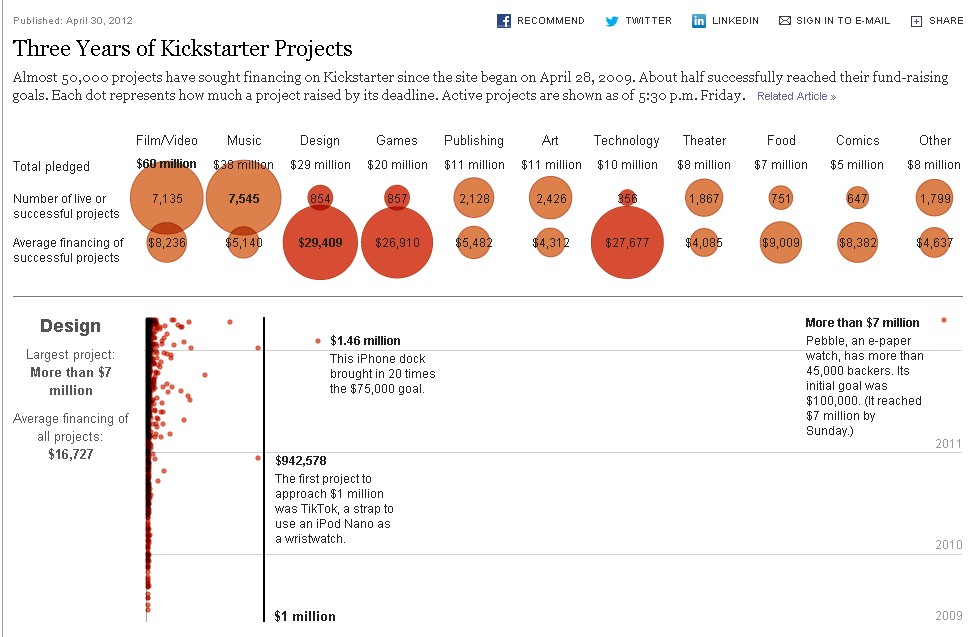

The New York Times did a well-executed research on this topic, which was translated into a data visualization. Already one year since its publishing, “Three years of Kickstarter” is still one of the few investigations ( if not the only one terms of visualization) that point out meaningful data about financing dynamics of crowdfunding platforms like Kickstarter.

A glimpse in New York Time’s visualization of Kickstarter’s finance dynamics. Click on the picture to explore it.

The visualization is revealing some interesting aspects. It starts by pointing out that only half of the projects were successful (April 2009 – April 2012). Then it continues to analyze the running and successful projects, according to categories. The visualization shows, for example, that the majority of the projects are in the ‘Film/Video’ and ‘Music’ categories ( over 7,000 – almost 9 times more than the number of projects in ‘Game’). The average requested financing is $8,000 (for films) and $5,000 (for music) – whereas a gaming project takes in over $29,000 on average – nearly 4 or 5 times more! Technology projects have similar big budgets with only 357 projects running or successful. Generally, budgets do no stray too much from the average, with hundred thousand or million dollar projects being a very rare case. This gives a good insight in the limits of the budgets that are successful in the according category. Interestingly, the average budget of successful projects s is always higher (sometimes as twice) than the average of all project budgets (successful and unsuccessful combined) within a particular category.

The visualization could benefit from a more clear methodology explanation (how is average calculated? Does ‘average financing’ refer to the average budget set up by the makers or the actual sum pledged for them – this is a significant difference as some projects end up with more than they intended). Perhaps a differentiation between “live”and “successful” projects would have been useful, as it is unclear how many projects have ended and uncertain how many of the live ones will ever succeed.

New York Times’ visualization does a good job in shedding light into some economical dynamics behind the platforms, and opens up more inquiries, many of which, if answered, would be highly relevant for future crowdfunders. Insights in average donation/project or average number of funders/ project would give an idea of how to focus on rewards value and what the reach should be in terms of audience. For the latter, it would be specifically interesting to determine if and how funders belong to the immediate network of the fundraisers or were previously unfamiliar to them (Renee Ridgway points out that 75% of the funders belong to the campaigners’ network and only 25% are actually new and distant contributors – does then the size of one’s network play a role in the project’s success?)*. It becomes more and more important to leave the hype of crowdfunding aside and look at the model with a more critical, inquiring mindset.

One of the pillars of the MoneyLab project is build a toolkit that would help guide creatives in approaching, understanding and deciding if crowdfunding is a model they want to invest time and effort in. It will also help them identify the most suitable crowfunding platform for their project, according to relevant criteria for them, as well as in-depth analysis of a wide range of platform dynamics.

*For a more qualitative analysis of crowdfunding dynamics in terms of success factors, Ethan Mollick’s paper on ‘The Dynamics of Crowdfunding: an Exploratory Study is a good read.